The Martial Arts and American Popular Media A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE December 8, 2016 TO: Members, Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade FROM: Committee Majority Staff RE: Hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 2016, at 10:00 a.m. in 2322 Rayburn House Office Building, the Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade will hold a hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” II. WITNESSES The Subcommittee will hear from the following witnesses: Randy Couture, President, Xtreme Couture; Lydia Robertson, Treasurer, Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports; Jeff Novitzky, Vice President, Athlete Health and Performance, Ultimate Fighting Championship; and Dr. Ann McKee, Professor of Neurology & Pathology, Neuropathology Core, Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Boston University III. BACKGROUND A. Introduction Modern mixed martial arts (MMA) can be traced back to Greek fighting events known as pankration (meaning “all powers”), first introduced as part of the Olympic Games in the Seventh Century, B.C.1 However, pankration usually involved few rules, while modern MMA is generally governed by significant rules and regulations.2 As its name denotes, MMA owes its 1 JOSH GROSS, ALI VS.INOKI: THE FORGOTTEN FIGHT THAT INSPIRED MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND LAUNCHED SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT 18-19 (2016). 2 Jad Semaan, Ancient Greek Pankration: The Origins of MMA, Part One, BLEACHERREPORT (Jun. 9, 2009), available at http://bleacherreport.com/articles/28473-ancient-greek-pankration-the-origins-of-mma-part-one. -

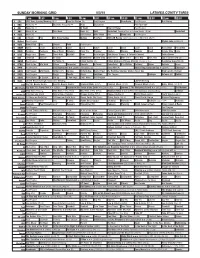

Sunday Morning Grid 5/3/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/3/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Equestrian PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Brooklyn Nets at Atlanta Hawks. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Pre-Race NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Afghan Luke (2011) (R) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Fast. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Father Brown 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

Shares Week 40

Shares Week 40 Cable channels' audience shares on different target groups Channel Cool Film+ RTL II RTL+ Sorozat + RTL GOLD Muzsika TV Target 18-49TSV 18-49TSV 18-49TSV 18-49TSV 18-49TSV 18-49TSV 18-49TSV Daypart 02:00-25:59 02:00-25:59 02:00-25:59 02:00-25:59 02:00-25:59 02:00-25:59 02:00-25:59 Jan 2016 5.1 5.4 2.0 1.3 0.6 0.3 0.5 Past Feb 2016 5.7 4.6 1.9 1.2 0.5 0.4 0.6 Mar 2016 4.8 4.9 1.9 1.6 0.4 0.3 0.6 Apr 2016 4.9 5.2 2.2 1.3 0.4 0.4 0.5 DATEGROUP May 2016 4.9 5.2 2.3 1.3 0.5 0.3 0.5 DATEGROUP Jun 2016 4.4 4.1 2.0 0.9 0.7 0.3 0.5 DATEGROUP Jul 2016 4.6 4.4 2.1 1.2 0.8 0.3 0.5 DATEGROUP Aug 2016 4.1 3.7 2.5 1.1 0.7 0.3 0.5 DATEGROUP Sep 2016 4.4 4.2 4.2 1.1 0.8 0.3 0.5 DATEGROUP Oct 2016 4.3 4.0 3.5 1.1 0.8 0.7 0.5 DATEGROUP Nov 2016 4.4 4.5 3.9 1.1 0.7 0.5 0.5 DATEGROUP Dec 2016 4.2 4.8 3.1 1.2 0.6 0.6 0.6 DATEGROUP Jan 2017 4.3 4.3 3.0 1.2 0.5 0.5 0.6 DATEGROUP Feb 2017 3.9 4.4 2.9 1.1 0.6 0.4 0.6 DATEGROUP Mar 2017 4.3 4.7 3.0 1.2 0.7 0.5 0.6 DATEGROUP Apr 2017 3.5 3.9 2.9 1.1 0.8 0.5 0.5 DATEGROUP May 2017 3.4 4.2 2.6 1.3 0.7 0.6 0.5 DATEGROUP Jun 2017 3.6 4.6 2.6 1.2 0.9 0.7 0.5 DATEGROUP Jul 2017 3.4 4.6 2.8 0.9 0.8 1.1 0.6 DATEGROUP Aug 2017 3.7 4.2 2.5 0.8 1.0 1.1 0.6 DATEGROUP Sep 2017 3.4 4.6 2.5 0.8 1.2 0.9 0.5 DATEGROUP Week 36 3.8 4.5 2.4 0.9 1.3 1.1 0.6 DATEGROUP Week 37 3.4 4.3 2.6 0.8 1.2 0.7 0.6 Present DATEGROUP Week 38 3.5 4.7 2.6 0.9 1.2 0.9 0.4 Week 39 3.0 4.6 2.5 0.9 1.2 0.8 0.4 DATEGROUP Week 40 3.0 5.0 2.6 1.1 1.1 0.8 0.5 DATEGROUP DATEGROUP DATEGROUP Source: Nielsen/M-RTL, Consolidated TSV figures, except last week Page 1 of 8 R-Time Sales & Marketing Shares Week 40 Cable channels' audience shares on different target groups Channel Comedy C. -

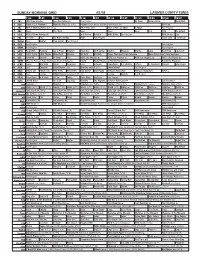

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Home Sweet Home

FINAL-1 Sat, Jun 30, 2018 5:22:48 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of July 8 - 14, 2018 Home sweet home Patricia Clarkson stars in “Sharp Objects” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 When a big city crime reporter (Amy Adams, “Arrival,” 2016) returns to her hometown to cover a string of gruesome killings, not all is what it seems. Jean-Marc Vallée (“Dallas Buyers Club,” 2013) reunites with HBO to helm another beloved novel adaptation in Gillian Flynn’s “Sharp Objects,” premiering Sunday, July 8, on HBO. The ensemble cast also includes Patricia Clarkson (“House of Cards”) and Chris Messina (“The Mindy Project”). WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE Salem, NH • Derry, NH • Hampstead, NH • Hooksett, NH ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 Newburyport, MA • North Andover, MA • Lowell, MA Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES IT’S MOLD ALLERGY SEASON We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE 1 x 3” Are you suffering from itchy eyes, sneezing, sinusitis or INSPECTIONS asthma? Alleviate your mold allergies this season. We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC Call or schedule your appointment online with New England Allergy today. CASH FOR GOLD Appointments Available Now on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 978-683-4299 at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. -

Film, Photojournalism, and the Public Sphere in Brazil and Argentina, 1955-1980

ABSTRACT Title of Document: MODERNIZATION AND VISUAL ECONOMY: FILM, PHOTOJOURNALISM, AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA, 1955-1980 Paula Halperin, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Directed By: Professor Barbara Weinstein Department of History University of Maryland, College Park My dissertation explores the relationship among visual culture, nationalism, and modernization in Argentina and Brazil in a period of extreme political instability, marked by an alternation of weak civilian governments and dictatorships. I argue that motion pictures and photojournalism were constitutive elements of a modern public sphere that did not conform to the classic formulation advanced by Jürgen Habermas. Rather than treating the public sphere as progressively degraded by the mass media and cultural industries, I trace how, in postwar Argentina and Brazil, the increased production and circulation of mass media images contributed to active public debate and civic participation. With the progressive internationalization of entertainment markets that began in the 1950s in the modern cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires there was a dramatic growth in the number of film spectators and production, movie theaters and critics, popular magazines and academic journals that focused on film. Through close analysis of images distributed widely in international media circuits I reconstruct and analyze Brazilian and Argentine postwar visual economies from a transnational perspective to understand the constitution of the public sphere and how modernization, Latin American identity, nationhood, and socio-cultural change and conflict were represented and debated in those media. Cinema and the visual after World War II became a worldwide locus of production and circulation of discourses about history, national identity, and social mores, and a space of contention and discussion of modernization. -

Outside the Cage: the Campaign to Destroy Mixed Martial Arts

OUTSIDE THE CAGE: THE CAMPAIGN TO DESTROY MIXED MARTIAL ARTS By ANDREW DOEG B.A. University of Central Florida, 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2013 © 2013 Andrew Doeg ii ABSTRACT This is an early history of Mixed Martial Arts in America. It focuses primarily on the political campaign to ban the sport in the 1990s and the repercussions that campaign had on MMA itself. Furthermore, it examines the censorship of music and video games in the 1990s. The central argument of this work is that the political campaign to ban Mixed Martial Arts was part of a larger political movement to censor violent entertainment. Connections are shown in the actions and rhetoric of politicians who attacked music, video games and the Ultimate Fighting Championship on the grounds that it glorified violence. The political pressure exerted on the sport is largely responsible for the eventual success and widespread acceptance of MMA. The pressure forced the sport to regulate itself and transformed it into something more acceptable to mainstream America. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 Historiography ........................................................................................................................... -

Farias, Priscila L. Et Wilke, Regina C. BORDERLINE GRAPHICS AN

BORDERLINE GRAPHICS: AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMA MARGINAL POSTERS REGINA C. WILKE PRISCILA L. FARIAS SENAC-SP / BRAZIL USP & SENAC-SP / BRAZIL [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION This paper presents a study on Brazilian Cinema The study of Cinema Marginal posters aims to Marginal film posters. It identifies the political and gathering information for a better understanding cultural context of the posters production, and of Brazilian design history. The posters selected considers their graphic, communicative and for this study are those designed for the films meaningful aspects. listed by Puppo (2008), in his catalogue for an In 1968, the Institutional Act #5 (AI-5) comes into exhibition of Cinema Marginal movies. force in Brazil, and, for the next ten years, the Initially, we describe the political and cultural country is haunted by the most violent period of context influencing Cinema Marginal , and military dictatorship. Cinema Marginal has its summarize the concepts that determine its heyday between 1968 and 1973, a period marked language. We then introduce the Brazilian graphic by the military regime (1964-1985). Such films arts environment of the era, and present the portray the spirit of that era in dissimilar ways identified authors of the posters. Finally, based on that alternate between eroticism, horror, an organization of the posters by affinity groups, romance and suspense, often with political we discuss the posters’ relation to the audiovisual messages in subtext. Its main shared language of the films, proposing a reflection on characteristics are the subversion of cinematic the visual, communicative and meaningful aspects language and experimental attitude. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

From Free Cinema to British New Wave: a Story of Angry Young Men

SUPLEMENTO Ideas, I, 1 (2020) 51 From Free Cinema to British New Wave: A Story of Angry Young Men Diego Brodersen* Introduction In February 1956, a group of young film-makers premiered a programme of three documentary films at the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank). Lorenza Mazzetti, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson thought at the time that “no film can be too personal”, and vehemently said so in their brief but potent manifesto about Free Cinema. Their documentaries were not only personal, but aimed to show the real working class people in Britain, blending the realistic with the poetic. Three of them would establish themselves as some of the most inventive and irreverent British filmmakers of the 60s, creating iconoclastic works –both in subject matter and in form– such as Saturday Day and Sunday Morning, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and If… Those were the first significant steps of a New British Cinema. They were the Big Screen’s angry young men. What is British cinema? In my opinion, it means many different things. National cinemas are much more than only one idea. I would like to begin this presentation with this question because there have been different genres and types of films in British cinema since the beginning. So, for example, there was a kind of cinema that was very successful, not only in Britain but also in America: the films of the British Empire, the films about the Empire abroad, set in faraway places like India or Egypt. Such films celebrated the glory of the British Empire when the British Empire was almost ending. -

Black and White Conversion

From www.adobe.com/designcenter Product used Adobe Photoshop CS2 Black and White Conversion “One sees differently with color photography than black and white...in short, visualization must be modified by the specific nature of the equipment and materials being used.” –Ansel Adams The original color image. (left) The adjusted black and white conversion. (center) The final color toned black and white image. (right) Seeing in black and white Black and white conversions are radical transformations of images. They’re about reestablishing the tonal founda- tions of an image. That’s quite different than dodging and burning, or lightening and darkening locally, which is a matter of accentuating existing tonal relationships. The Channels palette shows the red, green, and blue components of a color image. Each channel offers a useful black and white interpretation of the color image that you can use to adjust the color. The key concept is for you to use the color channels as black and white layers. 2 Conversion methods There are almost a dozen ways to convert an image from color to black and white; and you can probably find at least one expert to support each way as the best conversion method. The bottom line is that most conversion methods work reasonably well. The method that works best for you depends on your particular workflow and the tools that you’re comfortable with. The following method isn’t necessarily the best and it isn’t the fastest—it generates a larger file—but it offers you the most control and flexibility. Creating layers from channels offers you more control than any other conversion method. -

Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South.