Bsaauditof WE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

911 Cost Study

State of Washington 911 Cost Study Report to the Legislature Prepared pursuant to: Section 145, Chapter 6, Laws of 2019, Regular Session (Engrossed Substitute House Bill 1109) Washington Military Department December, 2020 PUBLICATION AND CONTACT INFORMATION This document is available on the Military Department’s website at: mil.wa.gov/e911 For more information contact: Adam Wasserman State E911 Coordination Office Building 20 Camp Murray, WA 98430-5011 Phone: 253-512-7468 [email protected] 1 | P a g e 911 Legislative Cost Study Report ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to Representative Ryu and the legislative body for your interest in 911 in the state of Washington. This study is the result of an extensive amount of work from many dedicated people in the Washington 911 community. We purposefully utilized the many talented people in the state who understand, respect and live with 911 daily. Each 911 County Coordinator was asked to participate as part of the study project team. Even the few who were unable to participate on specific workgroups due to other commitments, contributed by reviewing and providing critical feedback to the process. In addition to 911 County Coordinators, we drew upon the experience and talents of other dedicated professionals from the industry. Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) Directors, Public Safety Telecommunicators, Local Elected Officials and Telecommunication Industry Representatives all played a vital role in the process. The 911 Community in Washington is a uniquely engaged and collaborative group of dedicated professionals that come from different parts of the industry, with the sole purpose of establishing, maintaining and operating the best 911 system in the country. -

(OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (Inside) Interior Design

Publication Magazine Genre Frequency Language $10 DINNERS (OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (inside) interior design review Art & Photo English Bimonthly . -

Future, We Pride Ourselves on the Heritage of Our Brands and Loyalty of Our Communities

IPSO ANNUAL STATEMENT 2020 Introduction At Future, we pride ourselves on the heritage of our brands and loyalty of our communities. Every month, we connect more than 400 million people worldwide with their passions through brands that span technology, games, TV and entertainment, women’s lifestyle, music, real life, creative and photography, sports, home interest and B2B. First set up with one magazine in 1985, Future now boasts a portfolio of over 200 brands produced from operations in the UK, US and Australia. We seek to change people’s lives through sharing our knowledge and expertise with others, making it easy and fun for them to do what they want. Today, Future employs 2,300 employees worldwide and the company’s leadership structure as of 26 March 2021 is outlined in Appendix 2. Our core portfolio covers consumer technology, games/entertainment, women’s lifestyle, music, creative/design, home interest, photography, hobbies, outdoor leisure and B2B. We have over 100 magazines and publish over 400 one-off ‘bookazine’ products each year. Globally, 330+ million users access Future’s digital sites each month, and we have a combined social media audience of 104 million followers (a list of our titles/products can be found under Appendix 1a. & 1b.). In recent years, Future has made a number of acquisitions in the UK. These include Blaze Publishing, Imagine Publishing, Team Rock, Centaur’s Home Interest brands, NewBay Media, several Haymarket publications, two of Immediate Media’s cycling brands, Barcroft Studios and more recently and perhaps more significantly, TI Media. At the time of the last annual report the TI acquisition had still not completed, but from April 2020 TI Media has been fully under Future ownership. -

Libby Magazine Titles As of January 2021

Libby Magazine Titles as of January 2021 $10 DINNERS (Or Less!) 3D World AD France (inside) interior design review 400 Calories or Less: Easy Italian AD Italia .net CSS Design Essentials 45 Years on the MR&T AD Russia ¡Hola! Cocina 47 Creative Photography & AD 安邸 ¡Hola! Especial Decoración Photoshop Projects Adega ¡Hola! Especial Viajes 4x4 magazine Adirondack Explorer ¡HOLA! FASHION 4x4 Magazine Australia Adirondack Life ¡Hola! Fashion: Especial Alta 50 Baby Knits ADMIN Network & Security Costura 50 Dream Rooms AdNews ¡Hola! Los Reyes Felipe VI y Letizia 50 Great British Locomotives Adobe Creative Cloud Book ¡Hola! Mexico 50 Greatest Mysteries in the Adobe Creative Suite Book ¡Hola! Prêt-À-Porter Universe Adobe Photoshop & Lightroom 0024 Horloges 50 Greatest SciFi Icons Workshops 3 01net 50 Photo Projects Vol 2 Adult Coloring Book: Birds of the 10 Minute Pilates 50 Things No Man Should Be World 10 Week Fat Burn: Lose a Stone Without Adult Coloring Book: Dragon 100 All-Time Greatest Comics 50+ Decorating Ideas World 100 Best Games to Play Right Now 500 Calorie Diet Complete Meal Adult Coloring Book: Ocean 100 Greatest Comedy Movies by Planner Animal Patterns Radio Times 52 Bracelets Adult Coloring Book: Stress 100 greatest moments from 100 5280 Magazine Relieving Animal Designs Volume years of the Tour De France 60 Days of Prayer 2 100 Greatest Sci-Fi Characters 60 Most Important Albums of Adult Coloring Book: Stress 100 Greatest Sci-Fi Characters Of NME's Lifetime Relieving Dolphin Patterns All Time 7 Jours Adult Coloring Book: Stress -

MAGAZINE Print Licensing 2

MAGAZINE Print Licensing 2 AN ESTABLISHED AND PROVEN MODEL TO GENERATE REVENUE IN PRINT LICENSING We create content that connects people with their passions. What we offer our partners goes beyond the licensing of our content and brands. We provide access to our market leading insight and expertise and the tools to engage your audience, out-publish the competition and grow your business. With over 25 years experience in building profitable partnerships around the world, together we can build a successful publishing business in your territory. Passion | Innovation | Expertise 3 CONTENTS 1. About Future 2. Partnership Opportunity 3. Working With Us 4. The Brands 5. Digital Licensing 6. Events 4 WHY WE EXIST “We change people’s lives through sharing our knowledge and expertise with others, making it easy and fun for them to do what they want. ” 5 A GLOBAL COMPANY WITH GLOBAL SCALE 69m Social Media Fans Monthly Online 234m Users 1.1m Print Circulation Our influential magazines, online sites and events make Future a leading authority across various areas of interest including: Tech, Music, Gaming, Film, Photography, Creative & Design, Field Sports, Home Interest & Knowledge. Source: Google Analytics June-August 2017; Future Internal Records 6 KNOWLEDGE & EXPERTISE For Over 30 Years 1996 2007 T3 launches as a magazine TechRadar.com 1985 and grows as a launches and grows Chris Anderson multi-platform brand to a to become the UK’s 2013 launches successful website and #1 Tech Consumer Future Wins digital Amstrad Action market-recognised awards Brand -

Overdrive Magazine Title List, As of 11/16/2020 $10 DINNERS (OR LESS

OverDrive Magazine Title List, as of 11/16/2020 $10 DINNERS (OR LESS!) Adult Coloring Book: Stress Angels on Earth magazine (United States) Relieving Patterns (United (United States) States) 101 Bracelets, Necklaces, Animal Designs, Volume 1 and Earrings (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Stress Celebration Edition (United Relieving Patterns, Volume 2 States) 400 Calories or Less: Easy (United States) Italian (United States) Animal Tales (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Stress 50 Greatest Mysteries in the Antique Trader (United Relieving Peacocks (United Universe (United States) States) States) 52 Bracelets (United States) Aperture (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Stress 5280 Magazine (United Relieving Tropical Travel Apple Magazine (United States) Patterns (United States) States) 60 Days of Prayer (United Adweek (United States) Arabian Horse World (United States) States) Aero Magazine International Adirondack Explorer (United (United States) Arc (United States) States) AFAR (United States) ARCHAEOLOGY (United Adirondack Life (United States) Air & Space (United States) States) Architectural Digest (United Airways Magazine (United ADMIN Network & Security States) States) (United States) Art Nouveau Birds: A Stress All-Star Electric Trains Adult Coloring Book: Birds of Relieving Adult Coloring Book (United States) the World (United States) (United States) Allure (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Dragon Artists Magazine (United World (United States) America's Civil War (United States) States) Adult Coloring Book: Ocean ASPIRE -

911 Fee and Revenue Report to Congress

TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS ON STATE COLLECTION AND DISTRIBUTION OF 911 AND ENHANCED 911 FEES AND CHARGES FOR THE PERIOD JANUARY 1, 2019 TO DECEMBER 31, 2019 Submitted Pursuant to Public Law No. 110-283 FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Ajit Pai, Chairman December 8, 2020 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. KEY FINDINGS .................................................................................................................................... 2 III. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................... 3 IV. DISCUSSION ........................................................................................................................................ 5 A. Summary of Reporting Methodology .............................................................................................. 6 B. Overview of State 911 Systems ....................................................................................................... 8 C. Description of Authority Enabling Establishment of 911/E911 Funding Mechanism .................. 13 D. Description of State Authority that Determines How 911/E911 Fees are Spent ........................... 15 E. Description of Uses of State 911 Fees ........................................................................................... 17 F. Description -

Title Catalogue

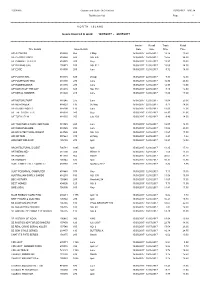

Ovato Retail Distribution - Title Catalogue TITLE CATALOGUE Alphabetical Listing June 2020 All Recommended Retail Prices (Inc GST), Trade (Exc GST) and/or Barcodes are subject to change at any time. Ovato Retail Distribution - Title Catalogue Updated 4/06/2020 Total Titles 2001 Count Title Code Title Frequency Sub Category RRP (inc GST) Trade ( Exc GST) Barcode Publisher 1 899430 10 MEN ~ AIR Quarterly General Titles - Men $ 29.99 $ 19.5587 9771463076840 Comag Magazine Marketing NZ$ Prop 2 105020 101 QUICK & EASY CROCHET MAKES Quarterly Sewing and Needlework Crafts $ 14.90 $ 9.7174 9781910196038 SEYMOUR INTERNATIONAL LTD - SEA 3 105025 110% GAMING Monthly Pre Teen $ 9.90 $ 6.4565 9772056777984 D C THOMSON & CO LTD 4 229535 200 POCKET WORDSEARCHES Bi monthly General Puzzle $ 5.95 $ 3.8804 9772044546004 MARKET FORCE (UK) LTD - SEA 5 105030 2000 AD WEEKLY Weekly Comics - General $ 9.50 $ 6.1957 9770262284241 SEYMOUR INTERNATIONAL LTD - SEA 6 108778 212 MAGAZINE Bi Annual Lifestyle - Adult $ 34.90 $ 22.7609 9772458956000 SEYMOUR INTERNATIONAL LTD - SEA 7 105035 25 BEAUTIFUL HOMES Monthly Home and Garden $ 13.00 $ 8.4783 9771369529228 MARKET FORCE (UK) LTD - SEA 8 239560 300 FIENDISH SUDOKU PUZZLES Monthly General Puzzle $ 6.50 $ 4.2391 9772041432003 MARKET FORCE (UK) LTD - SEA 9 105040 365 CROSSSTITCH DESIGNS Annual Sewing and Needlework Crafts $ 19.90 $ 12.9783 9772051669017 SEYMOUR INTERNATIONAL LTD - SEA 10 741980 40+ Monthly Restricted $ 24.50 $ 15.9783 74808029372 TSA CMG 11 402935 4X4 AUSTRALIA Monthly Truck $ 10.95 $ 7.1413 9313006010418 -

Social Action Program Outlined to Fight Injustice by Bob Mader the People and How Adequately It 1976, Deardon Explained

...... -------------------------------~-- ~--~ l Social action program outlined to fight injustice by Bob Mader the people and how adequately it 1976, Deardon explained. Campus Editor fulfills its pastoral mission. American culture and the teach This phase also hopes to examine ingsof the Church must test each The Catholic Church's Bicen the experiences of Catholics in other before any plan for social tennial Program to combat social their communities and find out ministry can begin. injustice "must involve the full what hopes Catholics have for the "To put it more precisely, if we community of the Church if it is to Church in the future. are to have a Catholic dialogue succeed," John Cardinal Dearden "Briefly put," Dearden stated, there must be a testing of the said last night. "the listening -learning phase is a experience and opinions of the The Archbishop of Detroit data gathering process. If done community by the normative outlined a two part social action well, it should provide a sampling teaching of the Church," Dearden program of the Catholic bishops of of what our people are thinking and said. America in his address to the what they are experiencing each The bishops intend to develop " Catholic Committee on Urban day." teaching document and a plan of Ministry <CCUM) conference. pastoral action" during the Detroit ''Basically, our plan for the Second phase: pastoral actio.a meeting, the Cardinal said, in American Church has two order to begin social change. dimensions," the Cardinal said. The reflection-response phase of "The Church, then, not merely "We can speak of a listening the Bicentennial Program will be a proclaims but is itself an agent of learning phase and a reflection sifting of the data obtained in the social justice. -

Interior Design Review Every Other Month Magazine SU

Title Frequency if provided Format Lending Model (inside) interior design review Every other month Magazine SU ¡Hola! Especial Viajes Twice per year Magazine SU ¡HOLA! FASHION Monthly Magazine SU ¡Hola! Fashion: Especial Alta Costura Twice per year Magazine SU ¡Hola! Mexico Every other week Magazine SU 0024 Horloges Twice per year Magazine SU 01net Every other week Magazine SU 11 Freunde Monthly Magazine SU 220 Triathlon Monthly Magazine SU 24H Brasil Weekly Magazine SU 25 Beautiful Homes Monthly Magazine SU 2nd セカンド Monthly Magazine SU 3D World Monthly Magazine SU 4x4 magazine Every other month Magazine SU 4x4 Magazine Australia Monthly Magazine SU 5280 Magazine Monthly Magazine SU 60 Days of Prayer Every other month Magazine SU 7 Jours Weekly Magazine SU 7 TV-Dage Weekly Magazine SU a+u Architecture and Urbanism Monthly Magazine SU ABC Organic Gardener Magazine Every other month Magazine SU ABC 互動英語 Monthly Magazine SU Accion Cine-Video Monthly Magazine SU AD (D) Monthly Magazine SU AD España Monthly Magazine SU AD France Every other month Magazine SU AD Italia Monthly Magazine SU AD Russia Monthly Magazine SU AD 安邸 Monthly Magazine SU Adega Monthly Magazine SU Adirondack Explorer Every other month Magazine SU Adirondack Life Monthly Magazine SU ADMIN Network & Security Every other month Magazine SU AdNews Every other month Magazine SU Advanced 彭蒙惠英語 Monthly Magazine SU Adventure Magazine Every other month Magazine SU Adweek Weekly Magazine SU AERO Magazine Monthly Magazine SU AERO Magazine América Latina Every other month Magazine SU -

Distribution List Page - 1

R56891A Gordon and Gotch (NZ) Limited 15/05/2017 9:06:14 Distribution List Page - 1 =========================================================================================================================================================== N O R T H I S L A N D Issues invoiced in week 14/05/2017 - 20/05/2017 =========================================================================================================================================================== Invoice Recall Trade Retail Title Details Issue Details Date Date Price Price A/F AUTOCAR 818030 855 3 May 15/05/2017 22/05/2017 12.72 19.50 A/F CLASSIC ROCK 818060 240 NO. 236 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 15.65 24.00 A/F COMPUTER ARTS 818075 205 May 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 13.37 20.50 A/F DR WHO (UK) 105971 105 NO. 512 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 15.65 24.00 A/F EDGE 818095 205 June 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 9.72 14.90 A/F FLIGHT INTL 818115 825 25 Apr 15/05/2017 22/05/2017 7.83 12.00 A/F FOURFOUR TWO 818130 275 June 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 16.96 26.00 A/F HOMES&GDNS 818170 275 June 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 12.98 19.90 A/F MATCH OF THE DAY 818215 825 NO. 454 15/05/2017 22/05/2017 8.15 12.50 A/F METAL HAMMER 818220 245 June 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 11.09 17.00 A/F MOTORSPORT 818245 275 June 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 13.04 20.00 A/F NEWSWEEK 818023 195 05 May 15/05/2017 22/05/2017 9.13 14.00 A/F RUGBY WORLD 818290 110 June 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 11.09 17.00 A/F THE CRICKETER 818320 285 May 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 14.97 22.95 A/F TOTAL FILM 818335 205 July 259 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 9.46 14.50 A/F TRACTOR & FARM HERITAGE 818345 225 June 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 12.07 18.50 A/F WOMAN&HOME 818365 250 June 15/05/2017 12/06/2017 13.04 20.00 AD ARCHITECTURAL DIGEST 243765 605 NO. -

KDL Overdrive Magazine Titles 1 Magazine $10 DINNERS (OR LESS

KDL OverDrive Magazine Titles 1 Magazine $10 DINNERS (OR LESS!) (inside) interior design review .net CSS Design Essentials ¡Hola! Cocina ¡Hola! Especial Decoración ¡Hola! Especial Viajes ¡HOLA! FASHION ¡Hola! Fashion: Especial Alta Costura ¡Hola! Los Reyes Felipe VI y Letizia ¡Hola! Mexico ¡Hola! Prêt-À-Porter 0024 Horloges 01net 10 Minute Pilates 10 Week Fat Burn: Lose a Stone 100 All-Time Greatest Comics 100 Greatest Comedy Movies by Radio Times 100 greatest moments from 100 years of the Tour De France 100 Greatest Sci-Fi Characters 100 Greatest Thriller Movies by Radio Times 101 Quick & Easy Crochet Makes 11 Freunde 15 Minute Fitness: Busy Girls Guide 150 Thrifty Knits 200 Scrapbooking Ideas 220 Triathlon 220 Triathlon presents the Beginner's Guide to Triathlon 25 Beautiful Homes 25 Years of the Hubble Space Telescope - from BBC Sky at Night Magazine 273 Papercraft & Card Ideas 2nd セカンド 3D Art & Design Tips, Tricks & Fixes 3D Make And Print 3D World 400 Calories or Less: Easy Italian 47 Creative Photography & Photoshop Projects 4x4 magazine 4x4 Magazine Australia 50 Baby Knits 50 Dream Rooms 50 Great British Locomotives 50 Greatest Mysteries in the Universe 50 Photo Projects Vol 2 50 Things No Man Should Be Without 50+ Decorating Ideas 500 Calorie Diet Complete Meal Planner https://kdl.overdrive.com/ 12/11/2020 KDL OverDrive Magazine Titles 2 Magazine 52 Bracelets 5280 Magazine 60 Days of Prayer 7 Jours 90 Glorious Years - The Queen's life decade by decade A brief guide to Apple TV A brief guide to Connecting your Apple gear A Brief