Middle Snake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Influence of a Dam on Fine-Sediment Storage in a Canyon River Joseph E

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 111, F01025, doi:10.1029/2004JF000193, 2006 Influence of a dam on fine-sediment storage in a canyon river Joseph E. Hazel Jr.,1 David J. Topping,2 John C. Schmidt,3 and Matt Kaplinski1 Received 24 June 2004; revised 18 August 2005; accepted 14 November 2005; published 28 March 2006. [1] Glen Canyon Dam has caused a fundamental change in the distribution of fine sediment storage in the 99-km reach of the Colorado River in Marble Canyon, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. The two major storage sites for fine sediment (i.e., sand and finer material) in this canyon river are lateral recirculation eddies and the main- channel bed. We use a combination of methods, including direct measurement of sediment storage change, measurements of sediment flux, and comparison of the grain size of sediment found in different storage sites relative to the supply and that in transport, in order to evaluate the change in both the volume and location of sediment storage. The analysis shows that the bed of the main channel was an important storage environment for fine sediment in the predam era. In years of large seasonal accumulation, approximately 50% of the fine sediment supplied to the reach from upstream sources was stored on the main-channel bed. In contrast, sediment budgets constructed for two short-duration, high experimental releases from Glen Canyon Dam indicate that approximately 90% of the sediment discharge from the reach during each release was derived from eddy storage, rather than from sandy deposits on the main-channel bed. -

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

Idaho Power Company's Fall Chinook Salmon Hatchery

IDAHO POWER COMPANY’S FALL CHINOOK SALMON HATCHERY PROGRAM Stuart Rosenberger, Paul Abbott, James Chandler 1221 W. Idaho St., Boise, Idaho Background The current Idaho Power Company (IPC) fall Chinook salmon program was established to provide mitigation for losses associated with the construction and operation of Brownlee, Oxbow, and Hells Canyon dams which together form the Hells Canyon Complex. IPC’s current mitigation goal is to produce 1 million fall Chinook salmon smolts annually (see Origination of Idaho Power Company’s Hatchery Mitigation Program section for more details). Oxbow Hatchery, funded by IPC and operated by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, is responsible for the incubation and rearing of up to 200,000 subyearling fall Chinook salmon. The hatchery is located on the Snake River downstream of Oxbow Dam near the IPC village known as Oxbow, Oregon (Figure 1). IPC also contracts with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) for the production of an additional 800,000 subyearling fall Chinook salmon that were originally reared at ODFW’s Umatilla Hatchery and are now reared at ODFWs’ Irrigon Hatchery, both of which are located near the town of Irrigon, Oregon. Fish reared at both Oxbow and Umatilla/Irrigon hatcheries are released into the Snake River directly below Hells Canyon Dam with the exception of brood years 2003 to 2005 in which some of the production was released at the Nez Perce Tribe’s Pittsburg Landing acclimation facility. Similar to other fall Chinook salmon programs in the Snake Basin, Oxbow and Umatilla/Irrigon hatcheries receive eyed eggs from Lyons Ferry Hatchery, as it is one of only two broodstock holding and spawning facilities for fall Chinook salmon in the Snake Basin. -

Trip Planner

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Trip Planner Table of Contents WELCOME TO GRAND CANYON ................... 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................... 3 GETTING TO GRAND CANYON ...................... 4 WEATHER ........................................................ 5 SOUTH RIM ..................................................... 6 SOUTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 7 NORTH RIM ..................................................... 8 NORTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 9 TOURS AND TRIPS .......................................... 10 HIKING MAP ................................................... 12 DAY HIKING .................................................... 13 HIKING TIPS .................................................... 14 BACKPACKING ................................................ 15 GET INVOLVED ................................................ 17 OUTSIDE THE NATIONAL PARK ..................... 18 PARK PARTNERS ............................................. 19 Navigating Trip Planner This document uses links to ease navigation. A box around a word or website indicates a link. Welcome to Grand Canyon Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park! For many, a visit to Grand Canyon is a once in a lifetime opportunity and we hope you find the following pages useful for trip planning. Whether your first visit or your tenth, this planner can help you design the trip of your dreams. As we welcome over 6 million visitors a year to Grand Canyon, your -

Wallowa County Community Sensitivity and Resilience

Wallowa County Community Sensitivity and Resilience This section documents the community’s sensitivity factors, or those community assets and characteristics that may be impacted by natural hazards, (e.g., special populations, economic factors, and historic and cultural resources). It also identifies the community’s resilience factors, or the community’s ability to manage risk and adapt to hazard event impacts (e.g., governmental structure, agency missions and directives, and plans, policies, and programs). The information in this section represents a snapshot in time of the current sensitivity and resilience factors in the community when the plan was developed. The information documented below, along with the findings of the risk assessment, should be used as the local level rationale for the risk reduction actions identified in Section 4 – Mission, Goals, and Action Items. The identification of actions that reduce a community’s sensitivity and increase its resilience assist in reducing the community’s overall risk, or the area of overlap in Figure G.1 below. Figure G.1 Understanding Risk Source: Oregon Natural Hazards Workgroup, 2006. Deleted: _________ County Deleted: Month Year Deleted: 2 Northeast Oregon Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan Page G-1 Community Sensitivity Factors The following table documents the key community sensitivity factors in Wallowa County. Population • Wallowa County has negative population growth (-1.3% change from 2000-2005) and an increasing number of persons aged 65 and above. In 2005, 20% of the population was 65 years or older; in 2025, 25% of the population is expected to be 65 years or older. Elderly individuals require special consideration due to their sensitivities to heat and cold, their reliance upon transportation for medications, and their comparative difficulty in making home modifications that reduce risk to hazards. -

Geology of the Grande Ronde Lignite Field, Asotin County

BRIAN J. BOYLE COMMISSIONER OF PUBLIC LANDS STATE OF WASHINGTON ART STEARNS, Supervisor RAYMOND LASMANIS, State Geologist DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES GEOLOGY OF THE GRANDE RONDE LIGNITE FIELD, ASOTIN COUNTY, WASHINGTON By Keith L. Stoffel Report of Investigations 27 1984 BRIAN J. BOYLE COMMISSIONER OF PUBLIC LANDS STATE OF WASHINGTON ART STEARNS, Supervisor RAYMOND LASMANIS, State Geologist DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES GEOLOGY OF THE GRANDE RONDE LIGNITE FIELD, ASOTIN COUNTY, WASHINGTON By Keith L. Stoff el Report of Investigations 27 Printed in the United States of America 1984 For sale by the Department of Natural Resources, Olympia, Washington Price $4.00 CONTENTS Page Abstract t • t t Ott t t t t t I It t t t t t too It Ott It t It t It t t t Ott t t t t t t t I t t I It t It t t It 1 Introduction . 2 Location and geographic setting . 2 Purpose and scope of study . 3 Methods of study . 3 Acknowledgments . 4 Geology of the Columbia Plateau . 6 General geologic setting . 6 Stratigraphic nomenclature . 7 Columbia River Basalt Group . 7 Ellensburg and Latah Formations . 8 Stratigraphy . 8 Regional stratigraphy . 8 Imnaha and Picture Gorge Basalts . 8 Yakima Basalt Subgroup . 9 Grande Ronde Basalt . 9 Wanapum Basalt . 9 Saddle Mountains Basalt ... .............. .. ........ .... 10 Stratigraphy of the Grande Ronde lignite field . 11 Structure ................................. ...................... .. 13 Evolution of the Blue Mountains province . 13 Structural geology of the Grande Ronde River-Blue Mountains region .......... 15 Folds . ............. .................... .............. 15 Faults . -

Characterization of Ecoregions of Idaho

1 0 . C o l u m b i a P l a t e a u 1 3 . C e n t r a l B a s i n a n d R a n g e Ecoregion 10 is an arid grassland and sagebrush steppe that is surrounded by moister, predominantly forested, mountainous ecoregions. It is Ecoregion 13 is internally-drained and composed of north-trending, fault-block ranges and intervening, drier basins. It is vast and includes parts underlain by thick basalt. In the east, where precipitation is greater, deep loess soils have been extensively cultivated for wheat. of Nevada, Utah, California, and Idaho. In Idaho, sagebrush grassland, saltbush–greasewood, mountain brush, and woodland occur; forests are absent unlike in the cooler, wetter, more rugged Ecoregion 19. Grazing is widespread. Cropland is less common than in Ecoregions 12 and 80. Ecoregions of Idaho The unforested hills and plateaus of the Dissected Loess Uplands ecoregion are cut by the canyons of Ecoregion 10l and are disjunct. 10f Pure grasslands dominate lower elevations. Mountain brush grows on higher, moister sites. Grazing and farming have eliminated The arid Shadscale-Dominated Saline Basins ecoregion is nearly flat, internally-drained, and has light-colored alkaline soils that are Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and America into 15 ecological regions. Level II divides the continent into 52 regions Literature Cited: much of the original plant cover. Nevertheless, Ecoregion 10f is not as suited to farming as Ecoregions 10h and 10j because it has thinner soils. -

Hells Canyon 5 Day to Heller

Trip Logistics and Itinerary 5 days, 4 nights Wine & Food on the Snake River in Hells Canyon Trip Starts: Minam, OR Trip Ends: Minam, OR Put-in: Hell’s Canyon Dam, OR Take-out: Heller Bar, WA (23 miles south of Asotin, WA) Trip length: 79 miles Class III-IV rapids Each Trip varies slightly with size of group, interests of guests, etc. This is a “typical” trip itinerary that will vary. Day before Launch: Stop at Minam on your way to your motel in Wallowa or Enterprise to pick up your dry bag and go over the morning itinerary. Day 1: If staying in Wallowa at the Mingo Motel we will pick you up at 6:15 am. If staying in Enterprise we will pick you up at the Ponderosa Motel in our shuttle van at 6:45 am. Travel to Hells Canyon Dam Launch site (3hr drive from Minam) with a bathroom break at the Hells Canyon Overlook. Meet your guides, go over basic safety talk, and load into rafts between 10 and 11 am. Lunch will be served riverside. Enjoy awe inspiring geology, spot wildlife. Run some of the biggest whitewater of the trip, first up Wild Sheep Rapid. Stop to scout Granite Rapid and view Nez Perce pictographs. Arrive in camp between 3-4pm. Evening camp time: swim, hike, play games, relax! Approximately 6pm: Wine and Hor D’oevres presented by Chef Andrae and the featured Winery. Approximately 7 pm dinner presented by chef Andrae Bopp. Day 2: Coffee is ready by 6 am. Leisurely breakfast between 7 and 8 am. -

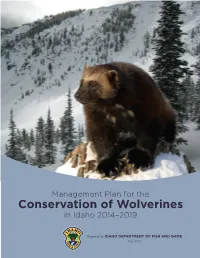

Wolverines in Idaho 2014–2019

Management Plan for the Conservation of Wolverines in Idaho 2014–2019 Prepared by IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME July 2014 2 Idaho Department of Fish & Game Recommended Citation: Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 2014. Management plan for the conservation of wolverines in Idaho. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise, USA. Idaho Department of Fish and Game – Wolverine Planning Team: Becky Abel – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Southeast Region Bryan Aber – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Upper Snake Region Scott Bergen PhD – Senior Wildlife Research Biologist, Statewide, Pocatello William Bosworth – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Southwest Region Rob Cavallaro – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Upper Snake Region Rita D Dixon PhD – State Wildlife Action Plan Coordinator, Headquarters Diane Evans Mack – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, McCall Subregion Sonya J Knetter – Wildlife Diversity Program GIS Analyst, Headquarters Zach Lockyer – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Southeast Region Michael Lucid – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Panhandle Region Joel Sauder PhD – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Clearwater Region Ben Studer – Web and Digital Communications Lead, Headquarters Leona K Svancara PhD – Spatial Ecology Program Lead, Headquarters Beth Waterbury – Team Leader & Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Salmon Region Craig White PhD – Regional Wildlife Manager, Southwest Region Ross Winton – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Magic Valley Region Additional copies: Additional copies can be downloaded from the Idaho Department of Fish and Game website at fishandgame.idaho.gov/wolverine-conservation-plan Front Cover Photo: Composite photo: Wolverine photo by AYImages; background photo of the Beaverhead Mountains, Lemhi County, Idaho by Rob Spence, Greater Yellowstone Wolverine Program, Wildlife conservation Society. Back Cover Photo: Release of Wolverine F4, a study animal from the Central Idaho Winter Recreation/Wolverine Project, from a live trap north of McCall, 2011. -

Heaven in Hell's Canyon

Northwest Explorer ONDAL ONDAL M M EN EN K K Left: Hiker at the boundary of Hell’s Canyon Wilderness. Right: Approaching Horse Heaven, elevation 8,100 feet on the Seven Devils Loop Trail in Hell’s Canyon Wilderness. June and July are good times to explore Washington’s southeast corner in the Wenaha-Tucannon area and in the nearby Hells Canyon area of Oregon and Idaho. Heaven in Hell’s Canyon Hiking two wilderness areas near Washington’s southeast corner By Ken Mondal finding places to backpack when the high jaw-dropping views. This hike can be country is snowed in. The Imnaha River done comfortably in 3-4 days. Seven Devils Loop in Hell’s is hikable virtually year round. An excellent description of hiking the Canyon is Heavenly On the Idaho side of the recreation Seven Devils Loop can be found in Hik- There is no question that the Grand area is a 215,000-acre wilderness area, ing Idaho by Maughan and Maughan, Canyon is one of the natural wonders which includes the Seven Devils Moun- published by Falcon. For the other hikes of the world. However, if one measures tains. The premier hike within this I would recommend Rich Landers’ 100 from the Snake River to the summit of wilderness is the Seven Devils Loop, a Hikes in the Inland Northwest. 9,393 foot He Devil Peak in the Seven rugged 29-mile round trip offering mag- Devils Mountains, this makes Hells nificent views into Hells Canyon many Choose Forgotten Wenaha- Canyon the deepest canyon in North thousands of feet below and equally Tucannon for Solitude America. -

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development River Characteristics - Sediment Transport - River Velocity - Terminology The illustrations below represent the 3 general classifications into which rivers are placed according to specific characteristics. These categories are: Youthful, Mature and Old Age. A Rejuvenated River, one with a gradient that is raised by the earth's movement, can be an old age river that returns to a Youthful State, and which repeats the cycle of stages once again. A brief overview of each stage of river development begins after the images. A list of pertinent vocabulary appears at the bottom of this document. You may wish to consult it so that you will be aware of terminology used in the descriptive text that follows. Characteristics found in the 3 Stages of River Development: L. Immoor 2006 Geoteach.com 1 Youthful River: Perhaps the most dynamic of all rivers is a Youthful River. Rafters seeking an exciting ride will surely gravitate towards a young river for their recreational thrills. Characteristically youthful rivers are found at higher elevations, in mountainous areas, where the slope of the land is steeper. Water that flows over such a landscape will flow very fast. Youthful rivers can be a tributary of a larger and older river, hundreds of miles away and, in fact, they may be close to the headwaters (the beginning) of that larger river. Upon observation of a Youthful River, here is what one might see: 1. The river flowing down a steep gradient (slope). 2. The channel is deeper than it is wide and V-shaped due to downcutting rather than lateral (side-to-side) erosion. -

Grand Canyon Escalade?

WHY ARE PROFITEERS STILL PUSHING Grand Canyon Escalade? Escalade’s memorandum with Ben Shelly said, if the Master Agreement is not executed “by JULY 1, 2013 ,” then the relationship with the Nation “shall terminate without further action .” a a l l a a b b e e h h S S y y e e l l r r a a M M THEIR ORIGINAL PLAN: • Gondola Tram to the bottom of the Grand Canyon • River Walk & Confluence Restaurant • A destination resort hotel & spa, other hotels, RV park • Commercia l/ retail spac e/opportunities, and an airport • 5,167 acres developed at the conflu ence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers . Escalade partner Albert Hale (left) and promoter Lamar Whitmer (right) present to Navajo Council, June 2014. People of Dine’ bi’keyah REJECT Grand Canyon Escalade. IT’S TIME TO ASK: • Where is the MASTER AGREEMENT ? • Who is going to pay $300 million or more • Where is the “ solid public support ” President for roads, water, and infrastructure? Shelly said he needed before December 31, 2012? • Where is the final package of legislation the • Where is support from Navajo presidential Confluence Partners said they delivered to the candidates and Navajo Nation Council? Navajo Nation Council Office of Legislative • Who is going to profit? Affairs on June 10, 2014? WE ARE the Save the Confluence families, generations of Navajo shepherds with grazing rights and home-site leases on the East Rim of Grand Canyon. “Generations of teachings and way of life are at stake.” “It has been a long hard journey and we have suffered enough.” –Sylvia Nockideneh-Tee Photo by Melody Nez –Delores Aguirre-Wilson, at the Confluence 1971 Resident Lucille Daniel stands firmly against Escalade.