Ludlow's Memoirs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citation Professor Adenike Grange Mb, Chb (St. Andrews

CITATION PROFESSOR ADENIKE GRANGE MB, CHB (ST. ANDREWS) DCH (LONDON) FMCPAED (NIG), FWACP, FAAP Professor Adenike Grange attended the Methodist Girls High School in Lagos and subsequently completed her secondary education at St. Francis College, Letchworth in the United Kingdom. In 1958 she was admitted to the famous University of St Andrews in Scotland where she read Medicine graduating in 1964. She did her house jobs at the Dudley Road Hospital in Birmingham before returning home in 1965. On her return she worked in various hospitals such as the Lagos Island Maternity, the Creek hospital and the Massey Street Children’s Hospital. She had always wanted to be Paediatrician and so in 1967 she returned to the UK where she was a senior house officer (paediatrics) at the St Mary’s Hospital for children and briefly at King’s College Hospital in London obtaining a Diploma in Child Health (DCH) in 1969. In 1971 she joined the residency training programme at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital. She joined the College of Medicine, University of Lagos as a lecturer in 1978 and was appointed a consultant to the Lagos University Teaching Hospital. She was promoted Senior Lecturer in 1981 and appointed Professor in 1995. She is the first female Professor of Paediatrics at the College of Medicine, University of Lagos. Professor Grange has served her institution creditably in various capacities including Headship of the Department of Paediatrics, Director, Institute of Child Health and lastly Dean of the School of Clinical Sciences, She has also served her country meritoriously as a consultant to the Federal Ministry of Health, WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and USAID. -

7Th Extraordinary Session of the Council of Ministers of the Organisation of the African Unity Being Held in Lagos 9Th December 1970

'b.a ~-o, ts>.AM{t(:(& acj ,., ~c.:f\.~tJ c u~ 7TH EXTRAORDINARY SESSION OF THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS OF THE ·ORGANISATION OF AFRICAN UNITY BEING HELD IN LAGOS 9m DECEMBER. 1970 ' 7TH EXTRAORDINARY SESSION OF THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS OF THE ORGANISATION OF AFRICAN UNITY PROGRAMME FOR THE OPENING (a) Opening by Chairman (b) Address by H.E. Major-General Yakubu Gowon, Head of the Federal Military Government, Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Nigeria. (c) Responses. (d) Suspension of Meeting and Invitees are requested to leave. (e) Meeting reassembles. PROVISIONAL AGENDA 1. (a) Adoption of the Agenda. (b) Organisation of Work. 2. Report of the Administrative Secretary-General. 3. Examination of the grave situation resulting for the African Continent from barbarous aggression of foreign mercenaries against Guinea. 4. (Any other Business). LIST OF MEMBER-STATES 1. Algeria 21. Malawi 2. Botswana 22. Malagasy • 3. Burundi 23. Mali 4. Cameroun , 24. Mauritania 5. Central Mrican Republic 25. Mauritius 6. Chad 26. Morocco 7. Congo, Peoples Republic 27. Niger . of the 8. Congo, Democratic 28. Nigeria Republic of the 9. Dahomey 29. Rwanda 10. Equatorial Guinea 30. Senegal 11. Ethiopia 31. Somalia 12. Gabon 32. Sudan 13. Gambia 33. Sierra Leone 14. Ghana 34. Tanzania 15. Guinea 35. Togo 16. Ivory Coast 36. Tunisia 17. Kenya 37. Swaziland 18. Liberia 38. Uganda 19. Libya 39. U.A.R. 20. Lesotho ·40. 'Upper Volta 41. Zambia ,I: ... ol t 1': l \ •• '• , .VENUE · ,; The plenary meetings will take place in the National Hall. Meetings of Committees will be held in the Senate building and the National Hall. -

The Center for Research Libraries Scans to Provide Digital Delivery of Its Holdings

The Center for Research Libraries scans to provide digital delivery of its holdings. In some cases problems with the quality of the original document or microfilm reproduction may result in a lower quality scan, but it will be legible. In some cases pages may be damaged or missing. Files include OCR (machine searchable text) when the quality of the scan and the language or format of the text allows. If preferred, you may request a loan by contacting Center for Research Libraries through your Interlibrary Loan Office. Rights and usage Materials digitized by the Center for Research Libraries are intended for the personal educational and research use of students, scholars, and other researchers of the CRL member community. Copyrighted images and texts may not to be reproduced, displayed, distributed, broadcast, or downloaded for other purposes without the expressed, written permission of the copyright owner. Center for Research Libraries Identifier: f-n-000001 Downloaded on: Jun 15, 2017 11:27:02 AM / ) ■ ¥ 10 .i* Coi 1969 i Federal RepubKc of Nigeria Official Gazette . 3. No. 66 LAGOS-19th September, 19d8 Yoh 55 I CONTENTS Page Page Central Bank of Nigeria—Return of Assets M ovements of O fficers • • 1248-53 and Liabilities as at the close of Business Transfer of Federal Government Officers to on 31st August, 1968 • » • • f • • 1266 the Lagos State Government • • 1254-60 Loss of Local Purchase Orders « • • • 1266 Appointment of a Notary Public .. 1261 Award of Scholarships for 1968-69 Academic Session • • • • • • * • » 1266-8 Registration as a Notary Public • « • • 1261 Scholarship Awards under the Nigerian Gulf Addition to the List of Notaries Public • « 1261 Oil Company Training Fund • • 1268-9 Grant of Pioneer Certificate . -

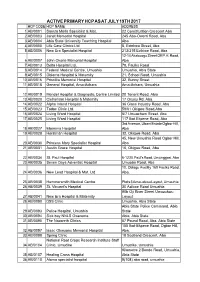

ACTIVE PRIMARY HCP AS at JULY 19TH 2017 HCP CODE HCP NAME ADDRESS 1 AB/0001 Sancta Maria Specialist & Mat

ACTIVE PRIMARY HCP AS AT JULY 19TH 2017 HCP CODE HCP NAME ADDRESS 1 AB/0001 Sancta Maria Specialist & Mat. 22 Constitutition Crescent Aba 2 AB/0003 Janet Memorial Hospital 245 Aba-Owerri Road, Aba 3 AB/0004 Abia State University Teaching Hospital Aba 4 AB/0005 Life Care Clinics Ltd 8, Ezinkwu Street, Aba 5 AB/0006 New Era Specialist Hospital 213/215 Ezikiwe Road, Aba 12-14 Akabuogu Street Off P.H. Road, 6 AB/0007 John Okorie Memorial Hospital Aba 7 AB/0013 Delta Hospital Ltd. 78, Faulks Road 8 AB/0014 Federal Medical Centre, Umuahia Umuahia, Abia State 9 AB/0015 Obioma Hospital & Maternity 21, School Road, Umuahia 10 AB/0016 Priscillia Memorial Hospital 32, Bunny Street 11 AB/0018 General Hospital, Ama-Achara Ama-Achara, Umuahia 12 AB/0019 Mendel Hospital & Diagnostic Centre Limited 20 Tenant Road, Abia 13 AB/0020 Clehansan Hospital & Maternity 17 Osusu Rd, Aba. 14 AB/0022 Alpha Inland Hospital 36 Glass Industry Road, Aba 15 AB/0023 Todac Clinic Ltd. 59/61 Okigwe Road,Aba 16 AB/0024 Living Word Hospital 5/7 Umuocham Street, Aba 17 AB/0025 Living Word Hospital 117 Ikot Ekpene Road, Aba 3rd Avenue, Ubani Estate Ogbor Hill, 18 AB/0027 Ebemma Hospital Aba 19 AB/0028 Horstman Hospital 32, Okigwe Road, Aba 45, New Umuahia Road Ogbor Hill, 20 AB/0030 Princess Mary Specialist Hospital Aba 21 AB/0031 Austin Grace Hospital 16, Okigwe Road, Aba 22 AB/0034 St. Paul Hospital 6-12 St. Paul's Road, Umunggasi, Aba 23 AB/0035 Seven Days Adventist Hospital Umuoba Road, Aba 10, Oblagu Ave/By 160 Faulks Road, 24 AB/0036 New Lead Hospital & Mat. -

Accredited Healthcare Providers

ACCREDITED HEALTHCARE PROVIDERS HEALTHCARE PROVIDERS'HEALTHCARE CODE PROVIDRES KEY AB/0001/P Sancta Maria Specialist & Mat. AB - ABIA AB/0002/P All Saints Hospital AD - ADAMAWA AB/0003/P Janent Memorial Hospital AK - AKWA IBOM AB/0004/P Abia State University Teaching Hospital AN - ANAMBRA AB/0005/P Life Care Clinics Ltd BA - BAUCHI AB/0006/P New Era Specialist Hospital BN - BENUE AB/0007/P John Okarie Memorial Hospital BO - BORNO AB/0008/P St.Anthony's Hospital BY - BAYELSA AB/0009/S Sancta Maria Specialist Hospital CR - CROSS RIVER AB/0010/S Abia State University Teaching Hospital DT - DELTA AB/0011/S New Era Specialist Hospital EB - EBONYI AB/0012/S Ucheoma Hospital ED - EDO AB/0013/P Delta Hospital Ltd. EK - EKITI AB/0014/P Federal Medical Centre, Umuahia EN - ENUGU AB/0015/P Obioma Hospital & Maternity FCT - ABUJA AB/0016/P Priscillia Memorial Hospital GM - GOMBE AB/0017/S Federal Medical Centre IM - IMO AB/0018/P General Hospital, Ama-Achara JG - JIGAWA AB/0019/P Mendel Hospital KB - KEBBI AB/0020/P Clehansan Hospital & Maternity KD - KADUNA AB/0022/P Alpha Inland Hospital KG - KOGI AB/0023/P Todac Clinic Ltd. KN - KANO AB/0024/P Living Word Hospital KT - KATSINA AB/0025/P Living Word Hospital KW - KWARA AB/0027/P Ebemma Hospital LA - LAGOS AB/0028/P Horstman Hospital NG - NIGER AB/0030/P Princess May Specialist Hospital NW - NASARAWA AB/0031/P Austin Grace Hospital OD - ONDO AB/0034/P St. Paul Hospital OG - OGUN AB/0035/P Seven Days Adventist Hospital OS - OSUN AB/0036/P New Lead Hospital & Mat. -

Tourist Sites: Products and Operations I Tsm 243 Tourist Sites: Products and Operations I

NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCES COURSE CODE: TSM243 COURSE TITLE: TOURIST SITES: PRODUCTS AND OPERATIONS I TSM 243 TOURIST SITES: PRODUCTS AND OPERATIONS I COURSE GUIDE TSM 243 TOURIST SITES: PRODUCTS AND OPERATIONS I Course Developer/Writer Dr. G. O. Falade National Open University of Nigeria Course Editor Dr. G. O. Falade National Open University of Nigeria Programme Leader Dr. G. O. Falade National Open University of Nigeria Course Coordinator Mr. M. A. Gana National Open University of Nigeria NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA TSM 243 TOURIST SITES: PRODUCTS AND OPERATIONS I National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island Lagos Abuja Office NOUN Building No.5 Dar-es-Salaam Street Off Aminu Kano Crescent Wuse II,Abuja Abuja e-mail: [email protected] URL: www.nou.edu.ng Published by National Open University of Nigeria Printed 2012 ISBN: 978-058-426-9 All Rights Reserved TSM 243 TOURIST SITES: PRODUCTS AND OPERATIONS I CONTENTS PAGE Introduction……………………………………………… 1 What You Will Learn in this Course…………………… 1 Course Aim……………………………………………… 1 Course Objectives……………………………………….. 2 Working through this Course……………………………... 2 Study Units……………………………………………… 3 Assignment File………………………………………….. 3 Final Examination and Grading…………………………. 4 Introduction HPM 243, Tourist sites, Products and Operations I is a first semester 200 levels, two – credit course. It is a required course for students in the B.Sc. Tourism Program. It may also be taken by any one who does not intend to do this program but is interested in learning about tourist sites, products and operations. This course will give you all the necessary information you desire to know about different tourist sites, various products and operations. -

Official. Gazette

Ya whe Federal Republic of Nigeria Official. Gazette No.79 7) LAGOS- 5th December, 1968 Vol, 55 1 CONTENTS Page Page Appointmentof Sir Samuel Manuwa as Act- Tenders . 1582-4 ing Chairman of the Federal Public Service Vacancies o. 1584 Commission . 1541 Board of Customs and Excise—Sale ofGoods 1584-7 Appointment of Sir Samuel Manuwaas Act- Increase in the Cost of Annual Supply of ing Chairman of the Police Service Commis- Federal Government Official Gazette .. 1588 sion .. ‘1542 Official Gazette—Renewal Notice ~ -. 1589 Appointment ofDr Saburi Oladeni Biobaku ;as ice~-Chancellor of the University of Lagos 1542-3 _ Movements of Officers 1543-51 Application for Registration of Trade Unions 1551 Inpex to LecaL Notices rv SupPLEMENT Appointmentof Registrar of Insurance 1552 Appointment of Inspector of Insurance 1552 LN, No. Short Title . Page Grant of Pioneer Certificate .. -. 1552 Loss of Local Purchase Orders « 1552-3 — Decree No. 57—Advisers to Military Export Duty on Rubber . ~. 1553 Governors, etc. (Ex-gratia Award) Customs and Excise Notice No. 7-—Transit Decree11968 . -. A793 - ‘Trade.. 1553-5 110 Paul Alias Noujaim Deportation ‘Treasury Returns—Statements Nos. 2-4 1556-60 Order 1968 .. + .. B391 Medical Register as at ist January, 1968 1561-80 111 Kenneth Awuoku Kwapong alias Monthly Purchases of Marketing Board aghae Derreck Deportation Order Produce covering the period 27th Septem- 196 B391 ber, 1968 to aiet October, 1968 (Month of 112 Kaduna PolytechnicAppointed Day October 1968) excluding Cocoa _Notice19: - B392 . Government Notice -

"Ofli Gazettesine “Ne.4 LAGOS -- 23Djuly, 1959 Es a Vets : “CONTENTS Fase

we 4 "oflI Gazettesine “Ne.4 _ LAGOS -- 23dJuly, 1959 eS a vets : “CONTENTS Fase . ee aaPage. 2 | Page. Governor-Goneral’s Movements 980 ‘Resolution of Board:ofDitettors:and Yetura: Petes Appointment of GovertionGoneral's- Depisty = 980 g, of Assete and Liabilities at the close of © businesson. 15th July, 1959—Central Bank DutiesutionofofthethaHfgkCorimileeintr{dnér forfor theth oo of Nigeria... ee ee we «> 996 General Executive Class—Exclusion of Posts 997 Appeintaatt ofPermanent Secreterien 9... 981 Examination in Native’ Languaged—Fetleral Movements of Officers wy as, on 981-7 Territory of Lagos ee ee: - 997, Appointmentof Board of Inquiry re Dispute Ni erian College of Teéthnology—Zaria : Afonveon MMossra_ Elder Dempsten Limitted. ranch; :Departmenti of . Architecture, and the NigerianUnionofSeamen. “b87 -“ “9| RBA,Fingl Examination, - -- "998 Enrolment in Spocial List Bof u.MOS. _ SB; Nigerian MilitaryFoicas 4.00 fee. 05988. Tageee8ears6 ning,College,oleaeeeeSuru-Lere 998. Probate: Notices 26 0 Eotge itt "15989400..‘NagirsLanguage Examination:June,1959 tela’ Teagonos. LandLas1dRegiatey+Appitofor Fire 990 Results 998° West African Currency Board as : . 998 Fedort,eebusdecriés Comnilestoti= Export Duty on Rubber eee »» 998 Appointment of Acting Chairman . 901 Tenders aa EES Cy 999. Appointment bf members of the Federal ;: Board ‘es ee oof : Srave- VACANCIES : Appointment of person, to at on.behalt of , University. College, rhedin’ ee oa port Licensing Authority ee99 University College; Peale ae «+. 1000 - PublioService'Commission,Northern i Appalatneat ofpotgon,10,set on bohalt of *" Region: 3°. ih? “oo 1000: rt LicensingAutho cH Ot eeMinistry’ of Health‘xia Boe al: Bp es Determination to render ae the office of a member of ‘Benutinesr Goromittes: ‘for: Western. -

Official Gazette - (No, 28 — — - Lagos-8Th June, 1983 Vol

Extraordinary Federal Republic of Niigeria Official Gazette - (No, 28 ——- Lagos-8th June, 1983 Vol. 70 Government Notice No. 386 . LISTOF REGISTERED AND LICENSED PHARMACISTS AS AT 3isr DECEMBER, 1982 . ANAMBRA STATE . - - Serial Name of Pharmacist Address ‘Licence No. * ; : . No. :1. Achonye,ioeLE oe ae2we BGRIdodoACeerieAchara ie ooee ee 015753 ‘ Agbalokomy,G.N. )on 4Uruma Set Boigu _ oI On 025917 . Ostreet, acta -* 025951. 7.° Aetlanaa, Be C 33 GansRoad, 025926 &.9. Ake eSWW. es - :- & Urm KakaStreet, Universityiversity ofof NiNigeria, Nsukka von 10, HLA, 68 Amawbia Street, En oT oD TD 025068 ~~ 11. Akubue, P. 1. (Professor) +e 3 Glen Taggart Street, University Campus, Nsukka 025987 _ 12, Akndoln, A. N. -- 99 Agbani Road, Uwani, Eougu .. we ©(025965 13. Alumona,A.I. .. ee -- 37 Neni Street, Ogul New Layout, Enugu -- -- 615755 14. Amobi, A. I. oe - oe: 21 Ochi Street’ Bax 190, oe -- 025940 15. Amobi, P. N. (Mrs) ae -- 12 Venn Road, North Onitsha - ve ee .025969 16. Amobi,J.A.U. .. 2.0 ww 12 VennRoad, North Onitsha oe ee oe =—010402 47. AmobiRA. ve ee 1cChime Lane, G.R.A., Enugusi totsia, -+ 923929 ee. co :. 015733 19. Anako, C. R. “f =) ~ Il Q2’Amechi SAPcet «+ 015752 Aneke, J. G. “+ ss +2 Clo Ukehe P.A.,Ukehe, Nsukka . -- : | 20.21,.Anohu,M.A. .. ..,, Bt Crescent GRA, Onitsha. -> +e 025988 "22, Anulude, J. 5. 1. 1. 8 Grant Street, Uwani, Enugu -2 ae we 040986 Aniocha,L.G.A. .. .. 015767 23. Anyike, E. N. ++ se es Box 3, Adazi-Nnukwu, ..- 025918 24. Arch, J.O. :. 20 Okolo Street, Onitsha oe eee 25 cc - 9 Ibiam Street, Uwani, Enugu 025938 26. -

The Center for Research Libraries Scans to Provide Digital Delivery of Its Holdings

The Center for Research Libraries scans to provide digital delivery of its holdings. In some cases problems with the quality of the original document or microfilm reproduction may result in a lower quality scan, but it will be legible. In some cases pages may be damaged or missing. Files include OCR (machine searchable text) when the quality of the scan and the language or format of the text allows. If preferred, you may request a loan by contacting Center for Research Libraries through your Interlibrary Loan Office. Rights and usage Materials digitized by the Center for Research Libraries are intended for the personal educational and research use of students, scholars, and other researchers of the CRL member community. Copyrighted images and texts may not to be reproduced, displayed, distributed, broadcast, or downloaded for other purposes without the expressed, written permission of the copyright owner. Center for Research Libraries Identifier: f-n-000001 Downloaded on: Jun 15, 2017 10:56:16 AM m \ N13 1969 opy Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette No. 79 f2_ LAGOS - 5th December, 1968 VoL 55 1 CONTENTS Page Page Appointment of Sir Samuel Manuwa as Act Tenders .. 1S82-4 ing Chainnan of tiie Federal Public Service Vacandes .. 1584 Commission .. .. .. 1541 Board of Customs and Excise—Sale of Goods 1584-7 Appointment of Sir Samuel as Act Increase in the Cost of Annual Supply of ing Chairman of the Police Service Conomis- Federal Government Official Gazette • • 1588 sion .. « • • t • • 1542 Official Gcsrette—Renewal Notice ■ .. .. 1589 Appointment of Dr Sabuii Olad^ Biobaku as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Lagos 1542-3 Movements of OflScers 1543-51 Application for Registration of Trade Unions 1551 Index to Legal Notices in Sueplembnt Appointment of Registrar of Insurance 1552 Appointment of Inspector of Insurance 1552 LM.No. -

Gazettes.Africa

geria Gazette No, 52 LAGOS- 25th July, 1963 Vol. 5¢° CONTENTS Page Page Birthday Honours, 1963, Federal List—Corri- Lagos Consumer Price Index--Lower gendum +e oe «» 1187 income Group .- an +» 1209 Movements of Officers 1188-97 Examination in Native Languages, Eastern Special Constabulary—Promotion -. 1197 Nigeria—December 1963 .. we -. 1209 Revocation of Appointmentof Governor of Cancellation of Certificate of Registration of a the Central Bank of Nigeria .- -- 1197 Trade: Union . os ae -- 1209 Revocation of Appointment of Deputy Appointment of . Licensed Buying Agents Governorof the Central Bank of Nigeria... 1198 under the 1964 Palm Kernels and Palm Oil Instrument of Appointment of the Governor Marketing Schemes .. -» 1210 of the Central Bank of Nigeria... = .- 1198 -Closing Date of the 1962-63 Cocoa Season and Instrument of Appointment ,of the Deputy Opening of 1963-64 Season - -- 1211 Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria... 1198 Free Primary Education, 1964—Registration Application for Registration of Trade Unions 1199 of Entitled Children oe . -» 1211 Collections registered during January to. June Air Passage Booking -» 1211 3. .. .- 1199-1202 Tenders a > ,.1211-2 Government. Promissory Notes “e -- 1203 Vacancies as a ae . 1212-8 Appointment of Members of the N’igerian UNESCO Vacancies .. _— .. 1218-9 Coal Corporation . e -s -. 1203 Customs and Excise Sales Notice 1219-20 Probate Notice -. .. .. -» 1203 Membership of the House of Representatives —Onitsha North Constituency .. -. 1204 Inpex To Lecat Notices iy SUPPLEMENT = Openingof Ibiaku Proposed Postal Agency .. 1204 LN. No. Short Title Page: Extension of Savings Bank Facilities to Shendam Postal Agency .. -. 1204 86 Entitlement to Practise as Barristers - Loss of Local Purchase Orders, etc. -

The Center for Research Libraries Scans to Provide Digital Delivery of Its Holdings

The Center for Research Libraries scans to provide digital delivery of its holdings. In some cases problems with the quality of the original document or microfilm reproduction may result in a lower quality scan, but it will be legible. In some cases pages may be damaged or missing. Files include OCR (machine searchable text) when the quality of the scan and the language or format of the text allows. If preferred, you may request a loan by contacting Center for Research Libraries through your Interlibrary Loan Office. Rights and usage Materials digitized by the Center for Research Libraries are intended for the personal educational and research use of students, scholars, and other researchers of the CRL member community. Copyrighted images and texts may not to be reproduced, displayed, distributed, broadcast, or downloaded for other purposes without the expressed, written permission of the copyright owner. Center for Research Libraries Identifier: f-n-000001 Downloaded on: Jul 23, 2018, 12:26:44 PM m \ N13 1969 opy Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette No. 79 f2_ LAGOS - 5th December, 1968 VoL 55 1 CONTENTS Page Page Appointment of Sir Samuel Manuwa as Act Tenders .. 1S82-4 ing Chainnan of tiie Federal Public Service Vacandes .. 1584 Commission .. .. .. 1541 Board of Customs and Excise—Sale of Goods 1584-7 Appointment of Sir Samuel as Act Increase in the Cost of Annual Supply of ing Chairman of the Police Service Conomis- Federal Government Official Gazette • • 1588 sion .. « • • t • • 1542 Official Gcsrette—Renewal Notice ■ .. .. 1589 Appointment of Dr Sabuii Olad^ Biobaku as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Lagos 1542-3 Movements of OflScers 1543-51 Application for Registration of Trade Unions 1551 Index to Legal Notices in Sueplembnt Appointment of Registrar of Insurance 1552 Appointment of Inspector of Insurance 1552 LM.No.