The Storz Stations Disc Jockey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

The Texas Observer APRIL 17, 1964

The Texas Observer APRIL 17, 1964 A Journal of Free Voices A Window to The South 25c A Photograph Sen. Ralph Yarborough • • •RuBy ss eII lee we can be sure. Let us therefore recall, as we enter this crucial fortnight, what we iciaJ gen. Jhere know about Ralph Yarborough. We know that he is a good man. Get to work for Ralph Yarborough! That is disputed, for some voters will choose to We know that he is courageous. He has is the unmistakable meaning of the front believe the original report. not done everything liberals wanted him to page of the Dallas Morning News last Sun- Furthermore, we know, from listening to as quickly as we'd hoped, but in the terms day. The reactionary power structure is Gordon McLendon, that he is the low- of today's issues and the realities in Texas, out to get Sen. Yarborough, and they will, downest political fighter in Texas politics he has been as courageous a defender of unless the good and honest loyal Demo- since Allan Shivers. Who but an unscrupu- the best American values and the rights of crats of Texas who have known him for lous politician would call such a fine public every person of every color as Sam Hous- the good and honest man he is lo these servant as Yarborough, in a passage bear- ton was; he has earned a secure place in many years get to work now and stay at it ing on the assassination and its aftermath, Texas history alongside Houston, Reagan, until 7 p.m. -

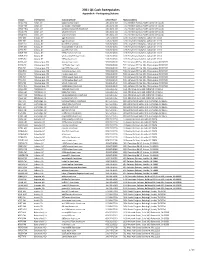

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station iHM Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM 1047kabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM -

NBC4 Anchors Colleen Williams and Chuck Henry Honored at PPB

WHO’S WHAT / WHAT’S WHERE MAY 2014 A Non-Profit Fraternal Organization of Radio and Television Broadcast Professionals ORDER YOUR LUNCHEON TICKETS NOW!! NBC4 Anchors Colleen Williams Friday, May 16, 2014 and Chuck Henry Honored at PPB PPB will honor singer, entertainer, and accomplished game show host Luncheon on March 28, 2014 PETER MARSHALL by Frank and Margie Barron ours before they The Diamond Circle Award sprang into action to will be presented to former H cover the earthquake, CBS News correspondent the NBC4 news team gath- DAVID DOW ered at the Pacific Pioneer Broadcasters awards lun- But it was weather wizard and cheon because the acclaimed all-around nice guy FRITZ news anchors COLLEEN COLEMAN who explained the WILLIAMS and CHUCK litany of reasons Williams and HENRY were being honored Henry were so deserving of the for more than 30 years of PPB honor. Fritz mentioned all award-winning journalism. the hard-hitting news stories It seemed everyone wanted that they have covered with to be there to praise them. exceptional professionalism, NBC4 president and general from earthquakes, fires, and manager STEVE CARL- FRITZ COLEMAN said that hon- riots, to Kardashian media STON said, “Their legacy is orees COLLEEN WILLIAMS and frenzies. “Anchor people earn CHUCK HENRY have turned the a tradition of excellence.” NBC4 Newsroom into a second their money when all hell family. (Photo: David Keeler) breaks loose.” At Sportsmen’s Lodge to laud Williams and Henry was sky reporter ALEX CALDER who noted that Colleen is so ded- PPB President CHUCK STREET presented the ART GILMORE Career icated to her job that during her free time she listens to the Achievement award to Colleen Williams and Chuck Henry. -

The Tin Pan Alley Pop Era (1885-Mid 1950'S)

OVERVIEW: The Foundation of Rock And Roll During the Great Migration more than 100,000 African-American laborers moved from the agricultural South to the urban North bringing with them their music and memories. Also, during the 1920’s the phonograph and the rise of commercial radio began to spread Hillbilly music and the Blues. This gave rise to an appreciating of American vernacular music, both white and black. Ultimately, the homogenizing effect of blending several regional musical styles and cultural practices gave birth to 1950’s rock and roll. The Tin Pan Alley Po ra 15-mid 1950’s) “The Great American Songbook” 1940’s Big Bands 1950’s Polar sic New York: “Tin Pan Alley” 14th St. and 2nd Ave. 1 Tin Pan Alley - New York 15-thogh 1940’s) The msic was distribted throgh sheet msic Proessional songwriters dominated the eriod George Gershwin and ole Porter omosers wrote or o msic Broadway and ilm ventally Tin Pan Alley tradition was relaced by the ock and oll tradition Tin Pan Alle – Ke oints 1. Written b a proessional oten non-peroring song-riters 2. ophisticated arrangeent 3. ncopated rhth accents on unepected, eak beats) 4. lever, ell-crated lrics 5. triving or upper-class sensibilities 6. Priar audience Adults 2 “Roots Music” - K oits 1. Riona ou o music 2. tu usicis 3. ot o tut 4. tou o titio 5. o maistream ican ists 6. o t i co cois “Roots Music” = he Blues D Country music he Blues Country Music 1920’s: Mississippi Delta Blues 1920’s: Cowboy Songs 1930’s: rban Blues 1930’s: Hillbilly Music 1940’s: ump Blues 1940’s: Country Swing -

Further Discoveries About Big Jon and Sparkie, Pt. 1

September-October 2020 www.otrr.org Groups.io No. 110 Contents Further Discoveries About Big Jon Big Jon and and Sparkie, Pt. 1 Sparkie 1 Stay Tuned for Gavin Callaghan Terror 7 Who Said That? 16 Since this publication is strictly devoted to OTR, one can forego the usual Purchasing Groups 20 preambles and explanations and delve directly into the heart of the matter: the Wistful Vistas 20 current state of Big Jon and Sparkie Remembering Ken studies. Piletic 21 In a sense, it is both the best of times The Joe Hehn and the worst of times. Worst, in the Collection 22 sense that although there is a great deal Maupin’s Musings of information out there, most of it is 23 uncodified, unformed, unsorted, and Four Star incorrect. And best, in the sense that Productions 25 there is a wide open and largely Remembering Don unexplored field for examination and Frey 26 endeavor – despite the fact that No Radio 100 Years School Today went off the air back in Ago 27 1982 and was on the air for three decades Acquisitions 30 before that. Contributors: In a sense, this is to be expected. One And thus, aside from a few devoted enthusiasts, studies have languished. Gavin Callaghan sees the same situation in the comic book But in the ignored also lies opportunity. Jim Cox field, in which superhero comics remain the fixed center of attention, while (so- Ryan Ellett Facebook called) “children’s comics” from Archie, Martin Grams Back in 2018, I founded the Big Jon and Larry Maupin Harvey, Gold Key and Dell remain Sparkie Fans page on Facebook. -

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows As of 01-01-2003

The Digital Deli Online - List of Known Available Shows as of 01-01-2003 $64,000 Question, The 10-2-4 Ranch 10-2-4 Time 1340 Club 150th Anniversary Of The Inauguration Of George Washington, The 176 Keys, 20 Fingers 1812 Overture, The 1929 Wishing You A Merry Christmas 1933 Musical Revue 1936 In Review 1937 In Review 1937 Shakespeare Festival 1939 In Review 1940 In Review 1941 In Review 1942 In Revue 1943 In Review 1944 In Review 1944 March Of Dimes Campaign, The 1945 Christmas Seal Campaign 1945 In Review 1946 In Review 1946 March Of Dimes, The 1947 March Of Dimes Campaign 1947 March Of Dimes, The 1948 Christmas Seal Party 1948 March Of Dimes Show, The 1948 March Of Dimes, The 1949 March Of Dimes, The 1949 Savings Bond Show 1950 March Of Dimes 1950 March Of Dimes, The 1951 March Of Dimes 1951 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1951 March Of Dimes On The Air, The 1951 Packard Radio Spots 1952 Heart Fund, The 1953 Heart Fund, The 1953 March Of Dimes On The Air 1954 Heart Fund, The 1954 March Of Dimes 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air With The Fabulous Dorseys, The 1954 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1954 March Of Dimes On The Air 1955 March Of Dimes 1955 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1955 March Of Dimes, The 1955 Pennsylvania Cancer Crusade, The 1956 Easter Seal Parade Of Stars 1956 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 Heart Fund, The 1957 March Of Dimes Galaxy Of Stars, The 1957 March Of Dimes Is On The Air, The 1957 March Of Dimes Presents The One and Only Judy, The 1958 March Of Dimes Carousel, The 1958 March Of Dimes Star Carousel, The 1959 Cancer Crusade Musical Interludes 1960 Cancer Crusade 1960: Jiminy Cricket! 1962 Cancer Crusade 1962: A TV Album 1963: A TV Album 1968: Up Against The Establishment 1969 Ford...It's The Going Thing 1969...A Record Of The Year 1973: A Television Album 1974: A Television Album 1975: The World Turned Upside Down 1976-1977. -

Radio Airplay and the Record Industry: an Economic Analysis

Radio Airplay and the Record Industry: An Economic Analysis By James N. Dertouzos, Ph.D. For the National Association of Broadcasters Released June 2008 Table of Contents About the Author and Acknowledgements ................................................................... 3 Executive Summary....................................................................................................... 4 Introduction and Study Overview ................................................................................ 7 Overview of the Music, Radio and Related Media Industries....................................... 15 Previous Evidence on the Sales Impact of Radio Exposure .......................................... 31 An Econometric Analysis of Radio Airplay and Recording Sales ................................ 38 Summary and Policy Implications................................................................................. 71 Appendix A: Options in Dealing with Measurement Error........................................... 76 Appendix B: Supplemental Regression Results ............................................................ 84 © 2008 National Association of Broadcasters 2 About the Author and Acknowledgements About the Author Dr. James N. Dertouzos has more than 25 years of economic research and consulting experience. Over the course of his career, Dr. Dertouzos has conducted more than 100 major research projects. His Ph.D. is in economics from Stanford University. Dr. Dertouzos has served as a consultant to a wide variety of private and public -

Available Videos for TRADE (Nothing Is for Sale!!) 1

Available Videos For TRADE (nothing is for sale!!) 1/2022 MOSTLY GAME SHOWS AND SITCOMS - VHS or DVD - SEE MY “WANT LIST” AFTER MY “HAVE LIST.” W/ O/C means With Original Commercials NEW EMAIL ADDRESS – [email protected] For an autographed copy of my book above, order through me at [email protected]. 1966 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS and NBC Fall Schedule Preview 1997 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS Fall Schedule Preview (not for trade) Many 60's Show Promos, mostly ABC Also, lots of Rock n Roll movies-“ROCK ROCK ROCK,” “MR. ROCK AND ROLL,” “GO JOHNNY GO,” “LET’S ROCK,” “DON’T KNOCK THE TWIST,” and more. **I ALSO COLLECT OLD 45RPM RECORDS. GOT ANY FROM THE FIFTIES & SIXTIES?** TV GUIDES & TV SITCOM COMIC BOOKS. SEE LIST OF SITCOM/TV COMIC BOOKS AT END AFTER WANT LIST. Always seeking “Dick Van Dyke Show” comic books and 1950s TV Guides. Many more. “A” ABBOTT & COSTELLO SHOW (several) (Cartoons, too) ABOUT FACES (w/o/c, Tom Kennedy, no close - that’s the SHOW with no close - Tom Kennedy, thankfully has clothes. Also 1 w/ Ben Alexander w/o/c.) ACADEMY AWARDS 1974 (***not for trade***) ACCIDENTAL FAMILY (“Making of A Vegetarian” & “Halloween’s On Us”) ACE CRAWFORD PRIVATE EYE (2 eps) ACTION FAMILY (pilot) ADAM’S RIB (2 eps - short-lived Blythe Danner/Ken Howard sitcom pilot – “Illegal Aid” and rare 4th episode “Separate Vacations” – for want list items only***) ADAM-12 (Pilot) ADDAMS FAMILY (1ST Episode, others, 2 w/o/c, DVD box set) ADVENTURE ISLAND (Aussie kid’s show) ADVENTURER ADVENTURES IN PARADISE (“Castaways”) ADVENTURES OF DANNY DEE (Kid’s Show, 30 minutes) ADVENTURES OF HIRAM HOLLIDAY (8 Episodes, 4 w/o/c “Lapidary Wheel” “Gibraltar Toad,”“ Morocco,” “Homing Pigeon,” Others without commercials - “Sea Cucumber,” “Hawaiian Hamza,” “Dancing Mouse,” & “Wrong Rembrandt”) ADVENTURES OF LUCKY PUP 1950(rare kid’s show-puppets, 15 mins) ADVENTURES OF A MODEL (Joanne Dru 1956 Desilu pilot. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context.