THE EXPRESSION and ENACTMENT of AGENCY in DESIGN/SCENOGRAPHY EDUCATION By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign Im Film: Eine Erste Bibliographie 2011

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Hans Jürgen Wulff; Ludger Kaczmarek Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie 2011 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12753 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wulff, Hans Jürgen; Kaczmarek, Ludger: Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik 2011 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 122). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12753. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0122_11.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft / Hamburg: Berichte und Papiere 122, 2011: Mode im Film. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Ludger Kaczmarek, Hans J. Wulff. ISSN 1613-7477. URL: http://www.rrz.uni-hamburg.de/Medien/berichte/arbeiten/0122_11.html Letzte Änderung: 20.2.2011. Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie. Zusammengest. v. Hans J. Wulff u. Ludger Kaczmarek Inhalt: da, wo die Hobos sind, er riecht wie einer: Also ist er Einleitung einer. Warum sollte man jemanden für einen anderen Bibliographien halten als den, der er zu sein scheint? In Nichols’ Direktoria Working Girl (1988) nimmt eine Sekretärin heimlich Texte für eine Zeit die Rolle ihrer Chefin an, und sie be- nutzt auch deren Garderobe und deren Parfüm. -

GULDEN-DISSERTATION-2021.Pdf (2.359Mb)

A Stage Full of Trees and Sky: Analyzing Representations of Nature on the New York Stage, 1905 – 2012 by Leslie S. Gulden, M.F.A. A Dissertation In Fine Arts Major in Theatre, Minor in English Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. Dorothy Chansky Chair of Committee Dr. Sarah Johnson Andrea Bilkey Dr. Jorgelina Orfila Dr. Michael Borshuk Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Leslie S. Gulden Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to my Dissertation Committee Chair and mentor, Dr. Dorothy Chansky, whose encouragement, guidance, and support has been invaluable. I would also like to thank all my Dissertation Committee Members: Dr. Sarah Johnson, Andrea Bilkey, Dr. Jorgelina Orfila, and Dr. Michael Borshuk. This dissertation would not have been possible without the cheerleading and assistance of my colleague at York College of PA, Kim Fahle Peck, who served as an early draft reader and advisor. I wish to acknowledge the love and support of my partner, Wesley Hannon, who encouraged me at every step in the process. I would like to dedicate this dissertation in loving memory of my mother, Evelyn Novinger Gulden, whose last Christmas gift to me of a massive dictionary has been a constant reminder that she helped me start this journey and was my angel at every step along the way. Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………ii ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………..………………...iv LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………..v I. -

0813122023.Pdf

Engulfed Page ii Blank ? Engulfed The Death of Paramount Pictures and the Birth of Corporate Hollywood BERNARD F. DICK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2001 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508–4008 05 04 03 02 01 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dick, Bernard F. Engulfed: the death of Paramount Pictures and the birth of corporate Hollywood / Bernard F. Dick. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8131-2202-3 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. Paramount Pictures Corporation–History. 2. Title. PN1999.P3 D53 2001 384'.8’06579494 00012276 This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. Manufactured in the United States of America. Contents Preface ix 1 Mountain Glory 1 2 Mountain Gloom 44 3 Barbarians at the Spanish Gate 85 4 Charlie’s Boys 109 5 The Italian Connection 126 6 The Diller Days 149 7 Goodbye, Charlie 189 8 Sumner at the Summit 206 Epilogue 242 End Titles 245 Notes 247 Index 259 Photo insert follows page 125 Page vi Blank For Katherine Page viii Blank Preface In Mel Brooks’s Silent Movie (1977), Sid Caesar nearly has a heart attack when he learns that a megaconglomerate called “Engulf and Devour” has designs on his little studio. -

Friendscriptv00003i00004 Opt.Pdf

ILLINOI S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. vol. 3, no. 4 Winter 1981-82 THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY FRIENDS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN ISSN 0192-5539 Motley Collection Acquired Costume Designs Span Fifty Years of Theater History The Friends, through their generosity, Since Motley designed costumes for have been instrumental in the many Shakespearean productions, the acquisition of an impressive collection costume collection will be a valuable of theater history-that of costume complement to the Library's already designs by the British company Motley. extensive Shakespeare collection The Motley Collection, which spans donated over the last 25 years by the 50 years of theater history, contains generous Library benefactor, Ernest more than 3,000 original costume Ingold. The collection will also be sketches, story boards and fabric valuable to those interested in costume samples from over 160 productions. design and generally for those Some of the designs are from interested in theater history. productions at the Shakespeare According to Dr. Mullin, the Memorial Theatre at collection, "documents the changing Stratford-upon-Avon, the Old Vic, trends in theatrical taste, conceptual Royal Court Theatre, operas presented approach and visual interpretation by the English National Opera, and through costumes and scenery. Using numerous commercial productions. In these sketches and designs, together the United States, Motley designed with the Library's other resources, costuming for such Broadway scholars can reconstruct individual productions as "South Pacific," productions and trace the evolution of "Can-Can," "Paint Your Wagon," "The theater style over several decades." Most Happy Fella," and "Peter Pan." Prof. -

Annual Report 2017–18

Annual Report 2017–18 1 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 7 Season Repertory and Events 13 Artist Roster 15 The Financial Results 48 Our Patrons 2 Introduction During the 2017–18 season, the Metropolitan Opera presented more than 200 exiting performances of some of the world’s greatest musical masterpieces, with financial results resulting in a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses—the fourth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Bellini’s Norma and also included four other new productions, as well as 19 revivals and a special series of concert presentations of Verdi’s Requiem. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 12th year, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office and media) totaled $114.9 million. Total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. All five new productions in the 2017–18 season were the work of distinguished directors, three having had previous successes at the Met and one making an auspicious company debut. A veteran director with six prior Met productions to his credit, Sir David McVicar unveiled the season-opening new staging of Norma as well as a new production of Puccini’s Tosca, which premiered on New Year’s Eve. The second new staging of the season was also a North American premiere, with Tom Cairns making his Met debut directing Thomas Adès’s groundbreaking 2016 opera The Exterminating Angel. -

Stage & Screen

STAGE & SCREEN Wednesday, April 28, 2021 DOYLE.COM STAGE & SCREEN AUCTION Wednesday, April 28, 2021 at 10am Eastern EXHIBITION Friday, April 23, Noon – 8pm Saturday, April 24, 10am – 6pm Sunday, April 25, Noon – 5pm Monday, April 26, 10am – 6pm And by Appointment at other times Safety protocols will be in place with limited capacity. Please maintain social distance during your visit. LOCATION Doyle Auctioneers & Appraisers 175 East 87th Street New York, NY 10128 212-427-2730 This Gallery Guide was created on (date) Please see addendum for any changes The most up to date information is available On DOYLE.COM Sale Info View Lots and Place Bids Doyle New York 1 6 CELESTE HOLM CELESTE HOLM Two Gold Initial Stickpins.14 kt., of the letters Celeste Holm's monogrammed luna mink "C" and "H" for Celeste Holm, signed Schubot, coat and cap. A floor length vintage fur coat, the ap. 3 dwts. interior labeled Robert Payne and the lining C The Celeste Holm Collection embroidered Celeste Holm. $300-500 C The Celeste Holm Collection $1,000-1,500 2 CELESTE HOLM Triple Strand Cultured Pearl Necklace with Gold and Garnet Clasp. Composed of three strands of graduated pearls ap. 9.5 to 6.5 mm., completed by a stylized flower clasp centering one oval garnet, framed by 7 round garnets, further tipped by 14 oval rose-cut garnets. Length 16 inches. C The Celeste Holm Collection $500-700 7 CELESTE HOLM Celeste Holm's monogrammed ranch mink 3 coat, hat and muffler. A three-quarter length CELESTE HOLM vintage fur coat, the interior labeled Robert Van Cleef & Arpels Gold, Cabochon Sapphire Payne and the lining with a label embroidered and Diamond Compact. -

Jocelyn Herbert Correspondence 1962-1989

The Beckett Collection Jocelyn Herbert correspondence 1962-1989 Summary description Held at: Beckett International Foundation, University of Reading Title: The Correspondence of Jocelyn Herbert Dates of creation: 1962 – 1989 Reference: Beckett Collection--Correspondence/HER Extent: 116 letters and postcards from Beckett to Jocelyn Herbert 1 letter from Samuel Beckett to George Devine 1 letter from Samuel Beckett to Jocelyn Herbert and George Devine 1 letter from Jocelyn Herbert to Samuel Beckett Language of material English unless otherwise stated Administrative information Immediate source of acquisition The correspondence was donated to the Beckett International Foundation by Jocelyn Herbert in 2002. Copyright/Reproduction Permission to quote from, or reproduce, material from this correspondence collection is required from the Samuel Beckett Estate before publication. Preferred citation Preferred citation: Correspondence of Samuel Beckett and Jocelyn Herbert, Beckett International Foundation, Reading University Library (RUL MS 5200) Access conditions Photocopies of the original materials are available for use in the Reading Room. Access to the original letters is restricted. Historical note 1917, 22 Feb. Born 1936 Joined the London Theatre Studio 1938 Married Anthony Lousada 1956 Joined George Devine’s English Stage Company at The Royal Court Theatre 1957 Designed her first production, Eugène Ionesco’s The Chairs 1958 Designer for Beckett’s Endgame and Krapp’s Last Tape, Royal Court Theatre 1962 Designer for Beckett’s Happy Days, Royal -

The Current Table of Contents

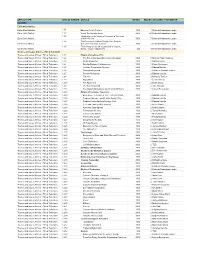

ARTICLE TYPE ARTICLE NUMBER ARTICLE WORDS IMAGES ASSIGNED CONTRIBUTOR VOLUME 1 Ed-in-Chief Articles Ed-in-Chief Articles 1.1.1 Editor-in-Chief’s Preface 1000 1 Deborah Nadoolman Landis Ed-in-Chief Articles 1.1.2 Visual Timelines by Genre 2000 40 Deborah Nadoolman Landis 1.1.3 Introduction to the History of Costume in Television Ed-in-Chief Articles and the Movies 7000 5 Deborah Nadoolman Landis 1.1.4 The Process of Costume Design, from Script to Ed-in-Chief Articles Screen in Film and Television 3000 5 Deborah Nadoolman Landis 1.1.5 Flow charts: on-set, off-set, process of costume Ed-in-Chief Articles design, costume department 250 4 Deborah Nadoolman Landis Themes and Issues Articles - Film & Television Themes and Issues Articles - Film & Television 1.2.1 History of Costume, Film Themes and Issues Articles - Film & Television 1.2.2 The Rise of the Specialist Costume Designer 2000 5 Michelle Tolini Finamore Themes and Issues Articles - Film & Television 1.2.3 Studio Production 2000 2 Natasha Rubin Themes and Issues Articles - Film & Television 1.2.4 Director/Designer Collaborations 1500 1 Drake Stutesman Themes and Issues Articles - Film & Television 1.2.5 Costume Department Directors 2000 2 Edward Maeder Themes and Issues Articles - Film & Television 1.2.6 Classical Hollywood 2000 2 Elizabeth Castaldo Lunden Themes and Issues Articles - Film & Television 1.2.7 Postwar Hollywood 2000 2 Edward Urquilla Themes and Issues Articles - Film & Television 1.2.8 Film Noir 2000 2 Kimberly Truhler Themes and Issues Articles - Film & Television 1.2.9 -

Samuel Beckett's Scenographic Collaboration with Jocelyn Herbert

Samuel Beckett's scenographic collaboration with Jocelyn Herbert Article Accepted Version McMullan, A. (2012) Samuel Beckett's scenographic collaboration with Jocelyn Herbert. Degrés, 149-150. pp. 1-17. ISSN 0770-8378 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/31236/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Ministère de la communauté française de Belgique All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Anna McMullan Film, Theatre and Television, University of Reading Citation: Anna McMullan, ‘Samuel Beckett’s Scenographic Collaboration with Jocelyn Herbert’, Degrés: Revue de Synthèse à Orientation Sémiotique (2012) Nos 149-150, (d) 1-17. SAMUEL BECKETT’S SCENOGRAPHIC COLLABORATION WITH JOCELYN HERBERT As a director, Beckett’s meticulous work with actors is legendary: his theatrical notebooks and accounts of his rehearsal processes emphasize the development of a precise choreography of speech, movement and gesture, such as the patterned movements of Estragon and Vladimir in Waiting for Godot, or Krapp’s glance over his shoulder towards the sensed presence of death lurking in the shadows in Krapp’s Last Tape1. However, when involved in the staging of his plays as director or advisor, Beckett was concerned not only with the actor’s performance but also with visual and practical details of the stage design which defines the stage world for both the actors and the audience. -

British Theatre Scenography the Reification of Spectacle Christine A

British Theatre Scenography The Reification of Spectacle Christine A. White Goldsmiths College London University Phd. 1 Abstract Over the last twenty years, the nature of theatre has changed due to the economic system of production which has led to the use of scenography to advertise the theatre product. Theatre has tried to make itself more attractive in the market place, using whatever techniques available. The technological developments of recent years have enabled the repackaging and sale of theatre productions both nationally and internationally. As a result theatre has become more 'designed' in an attempt to make it an attractive commodity. Scenography has become more prominent and this has changed the authorship of the theatre production, the dramatic text; the experts required by the new technologies have had a different involvement with the product, as they have actively contributed to the scenic image presented. Commercial values may have improved the integrity of theatre design and raised its profile within the profession, with theatre critics and with the academic world but it has proved unable to sell a production, which is ultimately lacking in theatricality and true spectacle. On particular occasions the gratuitous use of technology has been criticised, and as such, has been referred to as 'spectacle'. However, spectacle theatre does not simply mean theatre which uses technology, and so it has become imperative for the word spectacle to be more specifically applied, when used as a critical term to describe a form of theatre production. In this thesis, I intend to look at the significant factors that have led to the types of theatre presented in the last twenty years; to discuss these types of theatre in terms of their means of production and delivery to an audience, and to relate the change in scenographic values with a change in economic values; a change which has particularly affected the means of production, and as such is a vital beginning for any discussion of the scenography of the late twentieth century. -

I L L I N 0 I S University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

H I L L I N 0 I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. vol. 8, no. 1 Spring $T 6 * THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY FRIENDS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN SN01 ,5 9 m A C.Walter and Gerda B.Mortenson Establish Unique Library Professorship A University of Illinois alumnus, C. Walter Mortenson, and his wife, Gerda, of Newark, Delaware, have made a major gift to the University of Illinois Library at Urbana-Champaign through the UI Foundation. The gift of more than a million dollars will be used to fund a UIUC Library professorship in international library programs. The program will be established as the C. Walter Mortenson and Gerda B. Mortenson Distinguished Professorship for International Library Programs. It is believed to be the first professorship of its kind in the United States. The primary objective of the Fund will be to enhance and stimulate international library programs conducted by the University of Illinois Library at Urbana-Champaign for the promotion of international peace, health, education and understanding. In 1937 Mr. Mortenson earned a B.A. degree at the University of Illinois where he was elected to Phi Beta Announcement Kappa. He received a Ph.D. in was made at the annual Spring Gathering of the University Foundation in Chicago that a gift of more than a million dollars will Chemistry from the University be used by the UIUC Library to establish of the C. Walter Mortenson and Gerda B. Mortenson Distinguished Professorship Wisconsin for in 1940 and worked as a International Library Programs.