The Samurai Way of Baseball and the National Character Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

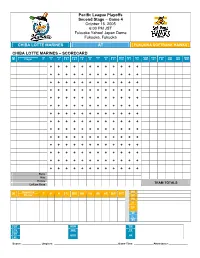

Pro Yakyu Gameday Packet

Pacific League Playoffs Second Stage – Game 4 October 16, 2005 6:00 PM JST Fukuoka Yahoo! Japan Dome Fukuoka, Fukuoka CHIBA LOTTE MARINES AT FUKUOKA SOFTBANK HAWKS CHIBA LOTTE MARINES – SCORECARD # Player P 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 AB R H RBI BB SO + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + Runs Hits Errors TEAM TOTALS Left on Base Opposing BK # T IP H R ER BB SO HB HR BF PIT Pitcher WP PB E DP W L SV SB HBP DB CS IBB TP SH GDP HR SF Scorer: _____________ Umpires: ____________________________________________Game Time: _____________ Attendance:_____________ Pacific League Playoffs Second Stage – Game 4 October 16, 2005 6:00 PM JST Fukuoka Yahoo! Japan Dome Fukuoka, Fukuoka CHIBA LOTTE MARINES AT FUKUOKA SOFTBANK HAWKS FUKUOKA SOFTBANK HAWKS – SCORECARD # Player P 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 AB R H RBI BB SO + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + Runs Hits Errors TEAM TOTALS Left on Base Opposing BK # T IP H R ER BB SO HB HR BF PIT Pitcher WP PB E DP W L SV -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Getting to Know Ms. Laden

Vol. XIV Issue 1 Harrison High School November 2009 A New Chapter in HHS History: Getting to Know Ms. Laden Jessica Peña Music Editor One of the biggest changes in of activities and clubs, and I observe spare or free time that you might have that it wasn’t very realistic compared the high school this school year is our teachers. on occasion? to the real world. It was different than new Assistant Principal, Ms. Jennifer Harrison. I really enjoy working in a Laden. Ms. Laden is here pursuing HH: Have you worked elsewhere prior JL: I swim, read and go interior deco- school with a diverse population. her passion, working with students and to coming to Harrison? rating shopping. watching them grow into young adults. HH: What did you do after high Recently, Ms. Laden sat down with the JL: I was a social studies teacher HH: Wow, interior decorating shop- school? Husky Herald and gave us a chance for 13 years and I was a department ping, that’s an interesting hobby. You to learn more about her interests and coordinator for the past three years at mentioned reading; what’s your favorite JL: I went to undergraduate school background. Fox Lane Middle and High School in book? at Holy Cross in Massachusetts to Bedford. major in History. Then, I went to NYU Husky Herald (HH): Have you always JL: I love To Kill A Mockingbird (by for graduate school and received my wanted to be an Assistant Principal? HH: Are you married? Do you have Harper Lee). -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

Baseball-Carp

HIRO CLUB NEWS ・ SPORTS ★ BASEBALL The Toyo Carp (Hiroshima's professional baseball team) plays about 60 games at the MAZDA Zoom-Zoom Stadium Hiroshima every year. GAME SCHEDULE ◆: Interleague Play MAY JUNE Friday, 3rd, 6:00 pm / vs. Yomiuri Giants Saturday, 1st, 2:00 pm / vs. Hanshin Tigers Saturday, 4th, 2:00 pm / vs. Yomiuri Giants Sunday, 2nd, 1:30 pm / vs. Hanshin Tigers Sunday, 5th, 1:30 pm / vs. Yomiuri Giants ◆ Friday, 7th, 6:00 pm / vs. Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks Friday, 10th, 6:00 pm / vs. Yokohama DeNA Baystars ◆ Saturday, 8th, 2:00 pm / vs. Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks Saturday, 11th, 2:00 pm / vs. Yokohama DeNA Baystars ◆ Sunday, 9th, 1:30 pm / vs. Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks Sunday, 12th, 1:30 pm / vs. Yokohama DeNA Baystars ◆ Tuesday, 18th, 6:00 pm / vs. Chiba Lotte Marines Tuesday, 14th, 6:00 pm / vs. Tokyo Yakult Swallows ◆ Wednesday, 19th, 6:00 pm / vs. Chiba Lotte Marines Wednesday, 15th, 6:00 pm / vs. Tokyo Yakult Swallows ◆ Thursday, 20th, 6:00 pm / vs. Chiba Lotte Marines Wednesday, 22nd, 6:00 pm / vs. Chunichi Dragons ◆ Friday, 21st, 6:00 pm / vs. Orix Baffaloes Friday, 31st, 6:00 pm / vs. Hanshin Tigers ◆ Saturday, 22nd, 2:00 pm / vs. Orix Baffaloes ◆ Sunday, 23rd, 1:30 pm / vs. Orix Baffaloes JULY AUGUST nd Tuesday, 2nd, 6:00 pm / vs. Tokyo Yakult Swallows Friday, 2 , 6:00 pm / vs. Hanshin Tigers rd Wednesday, 3rd, 6:00 pm / vs. Tokyo Yakult Swallows Saturday, 3 , 6:00 pm / vs. Hanshin Tigers th Thursday, 4th, 6:00 pm / vs. Tokyo Yakult Swallows Sunday, 4 , 6:00 pm / vs. -

*Japan ' ABSTRACT a Collection of Activities and Teaching Strategies Provides a Global Approach to Teachingabout Japan at the Elementary School Level

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 266 987 SO 016 940 AUTHOR Wooster, Judith S. TITLE Halfway Around the World Last Week. PUB DATE 81 NOTE 113p.; Eight pages containing illustrationsare marginally legible. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use- Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Asian Studies; Behavioral Objectives; Childrens Literature; *Cross Cultural Studies;Elementary Education; *Global Approach; InserviceTeacher Education; Instructional Materials; Learning Activities; Skill Develpment; *Social Studies;Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *Japan ' ABSTRACT A collection of activities and teaching strategies provides a global approach to teachingabout Japan at the elementary school level. Following a preface, material isdivided into three main sections. The first section outlinesinterdisciplinary skill goals and attitudinal skill goals of globallearning experiences. The second section, "For the Teacher Trainer" is designedto help teachers who will work with others to fosterglobal studies. A rationale for global education and the outlinefor a global education inservice are prLsented. The third section containsactivities focusing on Japan. All activities followa standard lesson plan containing theme, concepts, skills, anda student activity. Over ten activities focus on the Japaneseuse of space, Japanese children's literature and children's fun books,baseball in Japan and the United States, and comic book culture. (LP) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRSare the -

But Yanks' Rivals Perk Up

Griffs Copying '57 Pattern " m litlfc J&M; * But Yanks' Rivals Perk Up Ktttatap/ -¦* u 00: v Athletics Put Some Life Problems Grow Braves Hurt As Club Drops In AL Race With Sweep 16 of 20 Again By It th» AtMCltMd Pr*M Rocky Colavtto and Minnie Lack of By The rest of the American Minoso belted two-run homers Rt'RTON HAWKINS League beginning ¦Ur Rttl» Writer is to show for the Indians, with signs of life. Nobody is chal- Minoso NEW YORK. May 29-It for Buhl lenging those Yankees yet, but driving in three runs. Jack happened a little,later this Sub White Harslunan (&-3> year, It looks as if the Sox lost his third that'a all! By th« AuaclAttd Prm and Tlfcers are through play- In a row. 'Cal McLish put Laat season the Senators .started by losing games, The Braves may have the best ing patsy, while Kansas City complete-game victories back- 16 of 20 pitching In the National League, and Cleveland appear serious a drab drama which ended with about escaping the second divi- to-back for the first time in his the dismissal of Chuck Dressen to find - but their failure a re- *» sion year. msjor league career, which be- as manager. This m g. •>*.. / v X this season vJF placement for tore-armed Bob they've matched that perform- “ The Athletics, though 7'a gan in 1944 with Brooklyn. He _ behaving unpredlct- .A .a. 4 gXi'-i -r Buhl has been one reason they games behind New York, gave up six hits, wslked none ance after ably at the outset. -

Making Japan's National Game

Making Japan’s National Game Williams Making Japan's National Game.indb 1 10/9/20 3:18 PM Williams Making Japan's National Game.indb 2 10/9/20 3:18 PM Making Japan’s National Game A CULTURAL HISTORY OF BASEBALL IN JAPAN Blair Williams Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina Williams Making Japan's National Game.indb 3 10/9/20 3:18 PM Copyright © 2021 Blair Williams All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Williams, Blair, author. Title: Making Japan’s national game : a cultural history of baseball in Japan / Blair Williams. Description: Durham, North Carolina : Carolina Academic Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2020035907 (print) | LCCN 2020035908 (ebook) | ISBN 9781531015312 (paperback) | ISBN 9781531015329 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Baseball--Japan--History. | Baseball--Social aspects--Japan. | Japan--Social life and customs. Classification: LCC GV863.77.A1 B53 2020 (print) | LCC GV863.77.A1 (ebook) | DDC 796.3570952--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020035907 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020035908 Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America Williams Making Japan's National Game.indb 4 10/9/20 3:18 PM In memory of Ken Port Williams Making Japan's National Game.indb 5 10/9/20 3:18 PM Williams Making Japan's National Game.indb 6 10/9/20 3:18 PM Contents Acknowledgments xiii A Note on Transliterations -

Footing F&Faf

GENERAL NEWS SPORTS SPORTS footing f&faf THURSDAY, APRIL 23, 1953 C ** Harris Revamps Lineup, Hopes to Cash in on Vollmer Purchase •sygm Lj- Win, Lose or Draw Runnels Drops P- % Straight Face By FRANCIS STANN KIND OF SAD ABOUT the Detroit Tigers. It’s too early To Sixth Slotr 8-to-5 Choice to write ’em off as a last-place club again, but for a. fact they are acting like one. How does a ball club deteriorate so fast? Is the front office responsible? In 1950 the Tigers could have won the Wood Benched In Blue Grass American League pennant. They were out ” ' | Masterson Opposes in front until a late-Season slump enabled Correspondent 5 to 2 the Yankees to take it all. That was less Determined Shantz In Keeneland Test than three years ago. They were a good. As Home Stand Ends solid ball club then. Now they are shot full flMplNfSS| For Kentucky Derby' of weaknesses. By Burton Hawkins ly tha Associated Prass It could be the Tigers miss the late Clyde Vollmer. purchased from LEXINGTON. Ky.. April 23 - Wish Egan. He was more than chief scout. the Red Sox yesterday, will take Two of Native Dancer’s most Wish was a close adviser to Walter O. Briggs, over Ken Wood’s leftfleld job highly-esteemed rivals for the and Pete sr„ now dead, too. Briggs was not a prac- Runnels’ fifth spot In Kentucky Derby—Correspondent, i .mf|; the batting order when the Nats tical man, a impressive winner of two sprint baseball but, rather, fan. -

Sports Quiz When Were the First Tokyo Olympic Games Held?

Sports Quiz When were the first Tokyo Olympic Games held? ① 1956 ② 1964 ③ 1972 ④ 1988 When were the first Tokyo Olympic Games held? ① 1956 ② 1964 ③ 1972 ④ 1988 What is the city in which the Winter Olympic Games were held in 1998? ① Nagano ② Sapporo ③ Iwate ④ Niigata What is the city in which the Winter Olympic Games were held in 1998? ① Nagano ② Sapporo ③ Iwate ④ Niigata Where do sumo wrestlers have their matches? ① sunaba ② dodai ③ doma ④ dohyō Where do sumo wrestlers have their matches? ① sunaba ② dodai ③ doma ④ dohyō What do sumo wrestlers sprinkle before a match? ① salt ② soil ③ sand ④ sugar What do sumo wrestlers sprinkle before a match? ① salt ② soil ③ sand ④ sugar What is the action wrestlers take before a match? ① shiko ② ashiage ③ kusshin ④ tsuppari What is the action wrestlers take before a match? ① shiko ② ashiage ③ kusshin ④ tsuppari What do wrestlers wear for a match? ① dōgi ② obi ③ mawashi ④ hakama What do wrestlers wear for a match? ① dōgi ② obi ③ mawashi ④ hakama What is the second highest ranking in sumo following yokozuna? ① sekiwake ② ōzeki ③ komusubi ④ jonidan What is the second highest ranking in sumo following yokozuna? ① sekiwake ② ōzeki ③ komusubi ④ jonidan On what do judo wrestlers have matches? ① sand ② board ③ tatami ④ mat On what do judo wrestlers have matches? ① sand ② board ③ tatami ④ mat What is the decision of the match in judo called? ① ippon ② koka ③ yuko ④ waza-ari What is the decision of the match in judo called? ① ippon ② koka ③ yuko ④ waza-ari Which of these is not included in the waza techniques of -

Scenery Baseball Postmarks of Japan

JOURNAL OF SPORTS PHILATELY Volume 51 Spring 2013 Number 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS President's Message Mark Maestrone 1 Cricket & Philately: Cricket on the Peter Street 3 Subcontinent – Bangladesh Hungary Salutes London Olympics Mark Maestrone 10 and Hungarian Olympic Team & Zoltan Klein 1928 Olympic Fencing Postcards from Italy Mark Maestrone 12 Scenery Baseball Postmarks Norman Rushefsky 15 of Japan & Masaoki Ichimura 100th Grey Cup Game – A Post Game Addendum Kon Sokolyk 22 The next Olympic Games are J.L. Emmenegger 24 just around the corner! Book Review: Titanic: The Tennis Story Norman Jacobs, Jr. 28 The Sports Arena Mark Maestrone 29 Reviews of Periodicals Mark Maestrone 30 News of our Members Mark Maestrone 32 New Stamp Issues John La Porta 34 www.sportstamps.org Commemorative Stamp Cancels Mark Maestrone 36 SPORTS PHILATELISTS INTERNATIONAL CRICKET President: Mark C. Maestrone, 2824 Curie Place, San Diego, CA 92122 Vice-President: Charles V. Covell, Jr., 207 NE 9th Ave., Gainesville, FL 32601 3 Secretary-Treasurer: Andrew Urushima, 1510 Los Altos Dr., Burlingame, CA 94010 Directors: Norman F. Jacobs, Jr., 2712 N. Decatur Rd., Decatur, GA 30033 John La Porta, P.O. Box 98, Orland Park, IL 60462 Dale Lilljedahl, 4044 Williamsburg Rd., Dallas, TX 75220 Patricia Ann Loehr, 2603 Wauwatosa Ave., Apt 2, Wauwatosa, WI 53213 Norman Rushefsky, 9215 Colesville Road, Silver Spring, MD 20910 Robert J. Wilcock, 24 Hamilton Cres., Brentwood, Essex, CM14 5ES, England Store Front Manager: (Vacant) Membership (Temporary): Mark C. Maestrone, 2824 Curie Place, San Diego, CA 92122 Sales Department: John La Porta, P.O. Box 98, Orland Park, IL 60462 OLYMPIC Webmaster: Mark C.