Un Iversity of S Yd N Ey G Ro Unds C Onservation Manag Em Ent Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendices 2011–12

Art GAllery of New South wAleS appendices 2011–12 Sponsorship 73 Philanthropy and bequests received 73 Art prizes, grants and scholarships 75 Gallery publications for sale 75 Visitor numbers 76 Exhibitions listing 77 Aged and disability access programs and services 78 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services 79 Multicultural policies and services plan 80 Electronic service delivery 81 Overseas travel 82 Collection – purchases 83 Collection – gifts 85 Collection – loans 88 Staff, volunteers and interns 94 Staff publications, presentations and related activities 96 Customer service delivery 101 Compliance reporting 101 Image details and credits 102 masterpieces from the Musée Grants received SPONSORSHIP National Picasso, Paris During 2011–12 the following funding was received: UBS Contemporary galleries program partner entity Project $ amount VisAsia Council of the Art Sponsors Gallery of New South Wales Nelson Meers foundation Barry Pearce curator emeritus project 75,000 as at 30 June 2012 Asian exhibition program partner CAf America Conservation work The flood in 44,292 the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit ANZ Principal sponsor: Archibald, Japan foundation Contemporary Asia 2,273 wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012 President’s Council TOTAL 121,565 Avant Card Support sponsor: general Members of the President’s Council as at 30 June 2012 Bank of America Merill Lynch Conservation support for The flood Steven lowy AM, Westfield PHILANTHROPY AC; Kenneth r reed; Charles in the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit Holdings, President & Denyse -

A Life of Thinking the Andersonian Tradition in Australian Philosophy a Chronological Bibliography

own. One of these, of the University Archive collections of Anderson material (2006) owes to the unstinting co-operation of of Archives staff: Julia Mant, Nyree Morrison, Tim Robinson and Anne Picot. I have further added material from other sources: bibliographical A Life of Thinking notes (most especially, James Franklin’s 2003 Corrupting the The Andersonian Tradition in Australian Philosophy Youth), internet searches, and compilations of Andersonian material such as may be found in Heraclitus, the pre-Heraclitus a chronological bibliography Libertarian Broadsheet, the post-Heraclitus Sydney Realist, and Mark Weblin’s JA and The Northern Line. The attempt to chronologically line up Anderson’s own work against the work of James Packer others showing some greater or lesser interest in it, seems to me a necessary move to contextualise not only Anderson himself, but Australian philosophy and politics in the twentieth century and beyond—and perhaps, more broadly still, a realist tradition that Australia now exports to the world. Introductory Note What are the origins and substance of this “realist tradition”? Perhaps the best summary of it is to be found in Anderson’s own The first comprehensive Anderson bibliography was the one reading, currently represented in the books in Anderson’s library constructed for Studies in Empirical Philosophy (1962). It listed as bequeathed to the University of Sydney. I supply an edited but Anderson’s published philsophical work and a fair representation unabridged version of the list of these books that appears on the of his published social criticism. In 1984 Geraldine Suter published John Anderson SETIS website, to follow the bibliography proper. -

Georgia Kriz “We Aren’T Worth Enough to Them” Reviews Revues

Week 4, Semester 2, 2014 HONI I SHRUNK THE KIDS ILLUSTRATION BY AIMY NGUYEN p.12 Arrested at Leard p.15 In defense of the WWE Georgia Kriz “We aren’t worth enough to them” reviews revues. This past weekend it rained a lot. place, prevalence and prominence of However, since non-faculty lower tiers of funding, and thus can This was unfortunate for the cast cultural, minority and non-faculty revues traditionally receive less only book the smallest Seymour of Queer Revue, because the Union revues. funding than their faculty-backed space. And in order to graduate assigns us the Manning Forecourt counterparts, their road has not to the higher tiers of funding, to rehearse in on the weekends, and The problems facing non-faculty been easy. The Union allocates revues have to sell out this theatre so, when confronted with a veritable revues begin at their inception. between $4000 and $8000 to each completely. But with a limited downpour on Sunday morning, Entering the crowded revue revue. According to a spokesperson budget to spend on production, props we were forced to shop around for marketplace is an uphill battle from the Programs Office, the exact and advertising, smaller revues are another space. for new revues. After a period of amount allocated depends solely significantly hamstrung. And for dormancy, in 2011 several women upon which Seymour Centre theatre Queer Revue and Jew Revue, there But with all other rehearsal attempted to revive the Wom*n’s space a revue can sell out. Both Jew is no faculty to fall back on to fill the spaces occupied by faculty revues Revue. -

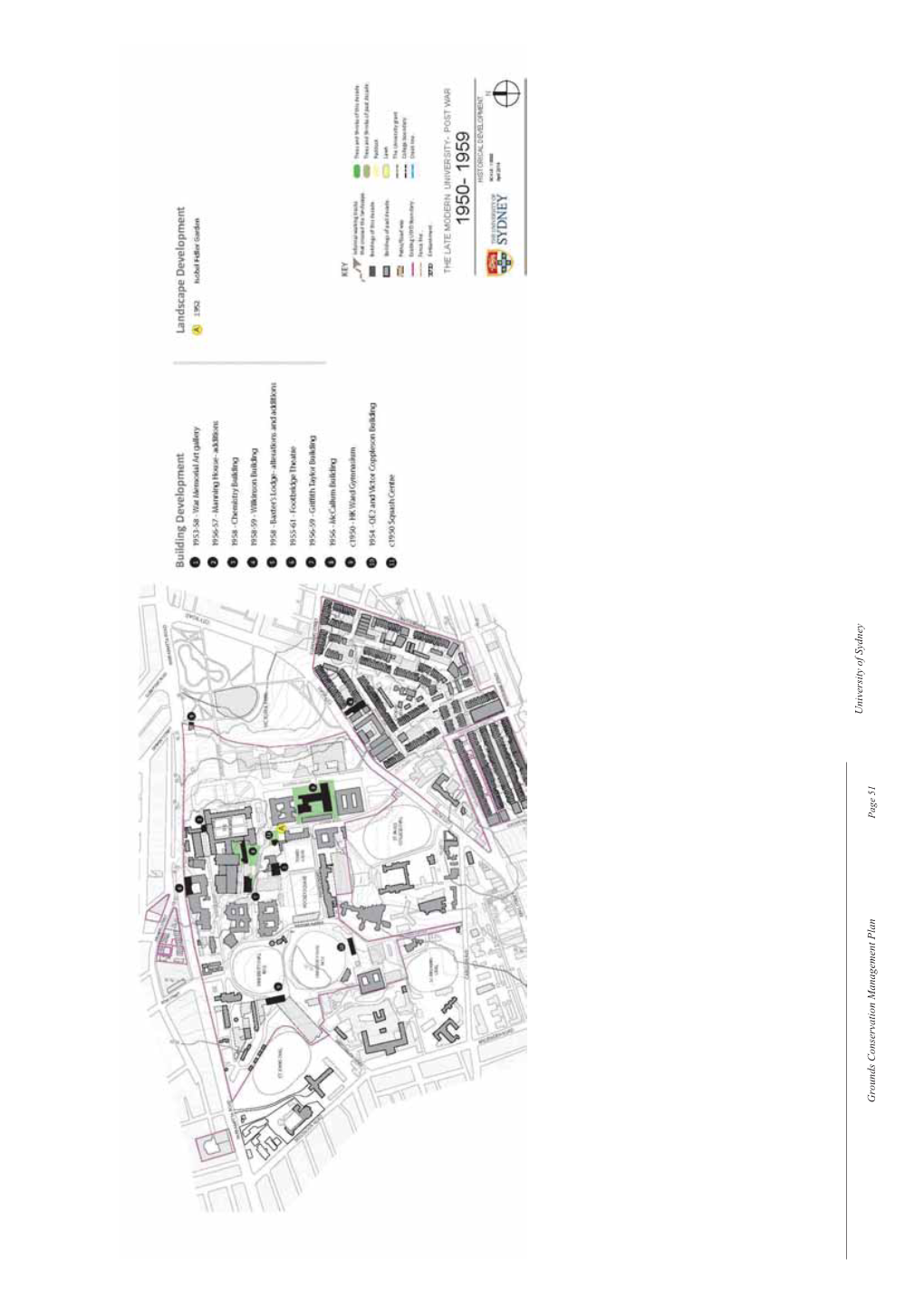

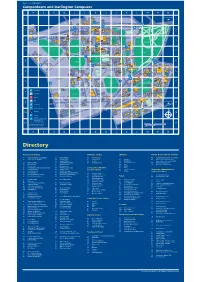

Camperdown and Darlington Campuses

Map Code: 0102_MAIN Camperdown and Darlington Campuses A BCDEFGHJKLMNO To Central Station Margaret 1 ARUNDEL STREETTelfer Laurel Tree 1 Building House ROSS STREETNo.1-3 KERRIDGE PLACE Ross Mackie ARUNDEL STREET WAY Street Selle Building BROAD House ROAD Footbridge UNIVERSITY PARRAMATTA AVENUE GATE LARKIN Theatre Edgeworth Botany LANE Baxter's 2 David Lawn Lodge 2 Medical Building Macleay Building Foundation J.R.A. McMillan STREET ROSS STREET Heydon-Laurence Holme Building Fisher Tennis Building Building GOSPER GATE AVENUE SPARKES Building Cottage Courts STREET R.D. Watt ROAD Great Hall Ross St. Building Building SCIENCE W Gate- LN AGRICULTURE EL Bank E O Information keepers S RUSSELL PLACE R McMaster Building P T Centre UNIVERSITY H Lodge Building J.D. E A R Wallace S Badham N I N Stewart AV Pharmacy E X S N Theatre Building E U ITI TUNN E Building V A Building S Round I E C R The H Evelyn D N 3 OO House ROAD 3 D L L O Quadrangle C A PLAC Williams Veterinary John Woolley S RE T King George VI GRAFF N EK N ERSITY Building Science E Building I LA ROA K TECHNOLOGY LANE N M Swimming Pool Conference I L E I Fisher G Brennan MacCallum F Griffith Taylor UNIV E Centre W Library R Building Building McMaster Annexe MacLaurin BARF University Oval MANNING ROAD Hall CITY R.M.C. Gunn No.2 Building Education St. John's Oval Old Building G ROAD Fisher Teachers' MANNIN Stack 4 College Manning 4 House Manning Education Squash Anderson Stuart Victoria Park H.K. -

A Billion Possibilities

A billion possibilities Stories from the University of Sydney’s INSPIRED philanthropic campaign A billion possibilities Editor Art director Cover and title page Produced by Marketing and Louise Schwartzkoff Katie Sorrenson illustrations Communications, the University Rudi de Wet of Sydney, June 2019. The Division of Alumni and Photographers University reserves the right Development Chris Bennett Contributing writers to make alterations to any The University of Sydney Louise Cooper Elissa Blake information contained within Level 2, Administration Building Corey Wyckoff Pip Cummings this publication without notice. (F23), NSW 2006 Stefanie Zingsheim George Dodd 19/7924 CRICOS 00026A sydney.edu.au/inspired Emily Dunn Photography assistant Katie Harkin Printing Daniel Grendon Hannah James Managed by Publish Partners Lenny Ann Low Louise Schwartzkoff INSP IRED Gabriel Wilder A geneticist’s cancer quest cancer geneticist’s A 40 leaf new a cannabis: Medicinal 34 New hope for an Aussie icon Aussie an for hope New 26 Attacking asthma Attacking 20 Farming’s robot revolution robot Farming’s 16 48 Scholarships that change lives 56 The project powerhouse 0 1 60 Teaching the teachers Campaign impact 06 Campaign in review 05 Contents Welcome 66 70 76 79 A new museum for Sydney for museum new A Gifts in the galleries the in Gifts Legacies of love of Legacies How surgery saved a child’s smile child’s a saved surgery How $1 BILLION FROM MORE THAN 64,000 DONORS SUPPORTING MORE THAN 4000 CAUSES INSPIRED The campaign to support the University of Sydney WELCOME From the Chancellor and Vice-Chancellor There are a billion reasons to celebrate as the knowledge they need to deliver major projects in the University of Sydney’s INSPIRED philanthropic fields ranging from technology to infrastructure. -

Genetic Counsellor

Genetic Counsellor Reports to Professor Glenda Halliday Brain and Mind Centre Organisational area Faculty of Medicine Central Clinical School Position summary The Genetic Counsellor will provide research participants and/or their family members with information and support regarding any genetic risks associated with the neurodegenerative conditions being researched, the implications for the participant and their families in participating in the genetic research, and whether participants have any concerns or issues that warrant other health professional referrals. More information about the specific role requirements can be found in the position description at the end of this document. Location Charles Perkins Centre Camperdown/Darlington Campus Type of appointment Full-time fixed term opportunity for 3 years. Flexible working arrangements will also be considered. Salary Remuneration package: $97,156 p.a. (which includes a base salary Level 6 $82,098 p.a., leave loading and up to 17% employer’s contribution to superannuation). How to apply All applications must be submitted online via the University of Sydney careers website. Visit sydney.edu.au/recruitment and search by reference number 2231/1017 for more information and to apply. 1 For further information For information on position responsibilities and requirements, please see the position description attached at the end of this document. Intending applicants are welcome to seek further information about the position from: Jude Amal Raj Research Officer 02 9351 0753 [email protected] For enquiries regarding the recruitment process, please contact: Sarah Daji Talent Acquisition Consultant 02 8627 6362 [email protected] The University of Sydney About us The University of Sydney is a leading, comprehensive research and teaching university. -

The University Archives – Record 2015

THE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES 2015 Cover image: Students at Orientation Week with a Dalek, 1983. [G77/1/2360] Forest Stewardship Council (FSC®) is a globally recognised certification overseeing all fibre sourcing standards. This provides guarantees for the consumer that products are made of woodchips from well-managed forests, other controlled sources and reclaimed material with strict environmental, economical social standards. Record The University Archives 2015 edition University of Sydney Telephone Directory, n.d. [P123/1085] Contact us [email protected] 2684 2 9351 +61 Contents Archivist’s notes............................... 2 The pigeonhole waltz: Deflating innovation in wartime Australia ............................ 3 Aboriginal Photographs Research Project: The Generous Mobs .......................12 Conservatorium of Music centenary .......................................16 The Seymour Centre – 40 years in pictures ........................18 Sydney University Regiment ........... 20 Beyond 1914 update ........................21 Book review ................................... 24 Archives news ................................ 26 Selected Accession list.................... 31 General information ....................... 33 Archivist‘s notes With the centenary of WWI in 1914 and of ANZAC this year, not seen before. Our consultation with the communities war has again been a theme in the Archives activities will also enable wider research access to the images during 2015. Elizabeth Gillroy has written an account of where appropriate. a year’s achievements in the Beyond 1914 project. The impact of WWI on the University is explored through an 2015 marks another important centenary, that of the exhibition showing the way University men and women Sydney Conservatorium of Music. To mark this, the experienced, understood and responded to the war, Archives has made a digital copy of the exam results curated by Nyree Morrison, Archivist and Sara Hilder, from the Diploma of the State Conservatorium of Music, Rare Books Librarian. -

The University Archives – Record 2007–8

TThehe UnUniversityiversity o off S Sydneyydney TheThe UniversityUniversity ArchivesArchives 20072006 - 08 Cover image: Undergraduates at Manly Beach, 1919 University of Sydney Archives, G3/224/1292. The University of Sydney 2007-08 The University Archives Archives and Records Management Services Ninth Floor, Fisher Library Telephone: + 61 2 9351 2684 Fax: + 61 2 9351 7304 www.usyd.edu.au/arms/archives ISSN 0301-4729 General Information Established in 1954, the Archives is a part of Contact details Archives and Records Management Services, reporting to the Director, Corporate Services within the Registrar’s Division. The Archives retains It is necessary to make an appointment to use the the records of the Senate, the Academic Board and University Archives. The Archives is available for those of the many administrative offices which use by appointment from 9-1 and 2-5 Monday to control the functions of the University of Sydney. Thursday. It also holds the archival records of institutions which have amalgamated with the University, Appointments may be made by: such as Sydney CAE (and some of its predecessors Phone: (02) 9351 2684 including the Sydney Teachers College), Sydney Fax: (02) 9351 7304 College of the Arts and the Conservatorium of E-mail: [email protected] Music. The Archives also houses a collection of photographs of University interest, and University Postal Address: publications of all kinds. In addition, the Archives Archives A14, holds significant collections of the archives of University of Sydney, persons and bodies closely associated with the NSW, AUSTRALIA, 2006 University. Web site: The reading room and repository are on the 9th www.usyd.edu.au/arms/archives floor of the Fisher Library, and the records are available by appointment for research use by all members of the University and by the general Archives Staff public. -

A History of Medical Administration in NSW 1788-1973

A History of Medical Administration in NSW 1788-1973 by CJ Cummins Director-General of Public Health, NSW (1959-1975) 2nd edition Photographic acknowledgments Images of St. Vincents Hospital, Benevolent Asylum and Scenes of Gladesville Hospital courtesy of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. Images of Lunatic Reception House – Darlinghurst, Department of Health Office, Broughton Hall Hairdressing Salon, Callan Park Recreation Grounds, Dr Morris, Dr Balmain and Garrawarra Hospital courtesy of the Bicentennial Copying Project, State Library of New South Wales. Image of The ‘Aorangi’ in quarantine courtesy of the Sam Hood collection, State Library of New South Wales. Image of Polio Ward – Prince Henry Hospital courtesy of photographer Don McPhedran and the Australian Photographic Agency collection, State Library of New South Wales. Image of John White (Principal Surgeon), George Woran (Surgeon of the ‘Sirius’), and Governor Phillip and young Aboriginal woman courtesy of Rare Books Collection, State Library of Victoria. NSW DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 73 Miller Street NORTH SYDNEY NSW 2060 Tel. (02) 9391 9000 Fax. (02) 9391 9101 TTY. (02) 9391 9900 www.health.nsw.gov.au This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study training purposes subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. It may not be reproduced for commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above, requires written permission from the NSW Department of Health. © NSW Department of Health 1979 First edition printed 1979 Second edition redesigned and printed October 2003 SHPN (COM) 030271 ISBN 0 7347 3621 5 Further copies of this document can be downloaded from the NSW Health website: www.health.nsw.gov.au October 2003 Preface This new preface is the result of a request from the NSW Department of Health to republish the original A history of medical administration in New South Wales, 1788-1973 Report. -

The University Archives – Record 2011

THE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES 2011 Façade left standing: Front Cover image: Sir Charles Nicholson’s home ‘The Grange’ in Totteridge, Hertfordshire, was destroyed by fire in 1899 along with Nicholson’s collections, including journals and correspondence. These would have been extensive and a valuable record of his life and work. Nonetheless, a small amount of Nicholson’s personal archives was donated to the University Archives in the late 1980s, having been located with other family members. P4/5/3. At right: NIcholson in his library prior to the fire. P4/5/2a CONTENTS 02 ARCHIVIST’S NOTES 16 DINTENFASS AND SPACE 03 PERSONAL ARCHIVES TODAY, MISSION STS-BIC 06 WHY DID DAVID ARMSTRONG 18 EdGEWORTH DAVID’S TRY— SET UP THE JOHN ANDERSON REAL OR IMAGINED RESEARCH ARCHIVE? 26 ARCHIVES NEWS 12 JOURNEYS THROUGH THE 28 ACCESSIONS, SEPTEMBER 2010– ARCHIVES: THE EXTENDED OLIVER SEPTEMBER 2011 FAMILY 14 SNAPSHOTS AND GOLD NUGGETS ISSN 0301-4729 2 ARCHIVIST’S NOTES TIM ROBINSON, UNIVERSITY ARCHIVIST The March 1984 issue of Record contains an article by Nyree Morrison, Reference Archivist, has written on the then University Archivist Ken Smith on personal the unexpected connection between the University archives. Ken was keen to promote awareness and and NASA’s Space Shuttle documented in the use of the ‘...personal records of individuals closely papers of Dr Leopold Dintenfass, former Director connected with...’ the University. The theme is of Haemorheology and Biorheology and a Senior repeated in this issue, with some changes reflecting Research Fellow from 1962-75. the intervening 27 years. Another long time user of the University Archives, The first article is by Anne Picot, Deputy University Dr David Branagan, has provided an insight to some Archivist, on the nature and challenges of personal of the better known University personalities of a ‘papers’ in the world of email and web 2.0. -

Econ History.Indb

PRELUDE Pragmatism versus principle: bringing commercial and economics education to the University of Sydney Th e Faculty of Economics established by the University of Sydney in 1920 formalised the availability of Economics and associated subjects in the education it provided. However, this subject had been of concern to the University and its teaching staff from its very inception 70 years earlier. On the eve of enacting the University, the government committee investigating Sydney’s need for its own university recognised that although the University started with the then traditional studies of Classics, Mathematics and the Natural Sciences, new fi elds of study, including history and political economy ‘will soon be found indispensable’ (cited in Goodwin, 1966, p. 546). Th e University’s foundation Professor of Classics, John Woolley, off ered optional lectures in political economy, two of which were published in the 1855 Sydney University Magazine. Th ese did not set out its principles but stressed the usefulness of its ‘laws’ for promoting social harmony and preserving freedom and individual liberty. Woolley invited a Prize Essay on ‘Th e Infl uence of Political Economy on the Course of History’ and asked his Logic students in an examination paper to evaluate critically the proposition that ‘Political Economy is the science of social well-being’ (Goodwin 1966, p. 547; Groenewegen and McFarlane 1990, pp. 47–49; and Groenewegen 1990, pp. 21–23). His colleague, Morris Birkbeck Pell, a Cambridge senior wrangler and foundation Professor of Mathematics, in 1856 read a paper to the Sydney Philosophical Society on the principles of political economy as applied to railways, a topic he also addressed in the fi rst issue of the Sydney University Magazine. -

FRESHERS' SPECIAL To-Day Is Freshman's Day

S.R.C. Whea lector** kite worn SPORTING GOODS HARRY HOPMAN'S SPORTS STORE wfclt • g—tli Lager are ukjacl to • Cmmm im pmwm»4 mmd mmIk 10% OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE SYDNEY UNIVERSITY STUDENTS REPRESENTATIVE COUNCIL HARRY HOPMAN'S UNVERSffY HOTEL SPORTS STORE Vol. II., No. MARCH 17. 1930. U Marti. Pkce. : FRESHERS' SPECIAL To-Day is Freshman's Day. Students' V ce-Chancellor's Message (As the S.R.C. Sees It.) Representative Council To Freshers:— Secretary Appointed "I shall have an opportunity of DONT FEEL STRANGE OR SHY addressing you at the Ceremony of A New Era. • At the lajit m«-«*tiriK < Matriculation mi March ;6. but I am Uepresentativo Council. glad to ncc-pt the invitation of the ARRANGEMENTS TO MAKE YOU FEEL AT HOME I Hill. A.C.I.S.. A.A.A.. Kdiior of "Hniii Soil" IO extend to pent-nil wen lary. you. at the ow ning of term, a cordial Whereas. in previous years, t* brunt of the welcome to Freshers Lent Term. 1930, opens to-day with great promise for students welcome in*" "in- midst. I hope you will epcedilv f—I <|iiite at home, as 1 has been mainly borne by the Clmtian Union, the recently-formed and of the University of Sydney. Organised into a corporate whole for that fill all-powerful Students' Representative Council has decided to establish the first time in its history, the student body has before it a future in I'nivei life. the first day of Lent Term as f icrhman's Day. which it can, if it will, take its proper place in the life of the Alma "The best advice I can give you is Mater.