Money and Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Threads Copyright © Rossen, 2011 Tuesday, March 5, 2013

Draft: Golden Threads Copyright © Rossen, 2011 Tuesday, March 5, 2013 Golden Threads Preamble My Family in Greece John Augustus Toole Who can tell which Angel of Good Fortune must have smiled upon the young loyalist Irishman, John Augustus Toole, when he joined the British Navy as a midshipman and sailed out to the Mediterranean sometime in the first decade of the 19th Century? He was landed on the enchanted island of Zante where he met the great love of his life, the Contessina Barbara Querini. In this book I will tell the story of their love, the disapproval of Barbara’s family and how it came about that the young British officer prevailed. It was his good fortune and hers that resulted in my family on the Ionian Islands in Greece. My life, four generations later, was succoured in the cradle of luxury and privilege that he, his children and grandchildren had created. Before I tell you the story of my remarkable life on these islands, a story resonant with living memory and fondness for the people who touched my life, I will describe in this preamble the times, places and people who came before me: the tales told to me as a child. Most of Greece was part of the Ottoman Empire at the time of John Augustus Toole’s arrival. The seven Ionian Islands, located on the west coast of Greece, had escaped Ottoman occupation as part of the Venetian Empire. In 1796 Venice fell to the French under Napoléon Bonaparte. In 1809, British forces liberated the island of Zante and soon after Cephalonia, Kythria and Lefkada. -

How Uk News Providers Engage Young Adult Audiences (Aged 16-34) on Digital and Social Media Platforms

‘OLD NEWS, YOUNG VIEWS’ HOW UK NEWS PROVIDERS ENGAGE YOUNG ADULT AUDIENCES (AGED 16-34) ON DIGITAL AND SOCIAL MEDIA PLATFORMS. by LEON HAWTHORNE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MA BY RESEARCH. Department of Film & Creative Writing School of English, Drama and Creative Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham June 2020 ii University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. iii Abstract This thesis examines the changing patterns of news consumption by young adults in the United Kingdom, aged 16 to 34 years old, and the editorial responses to this by leading television news broadcasters. It begins with a comprehensive review of the most recent literature on incidental news exposure, personalisation, echo chambers and filter bubbles; combining this with analyses of key reports by industry and governmental sources. It proposes a new taxonomy of news consumption behaviours, and a new visual taxonomy of news using the RGB (red, green, blue) colour spectrum. Senior editors at ITV News, Channel 4 News, 5 News and Sky News were interviewed to provide insights into current digital strategies. -

The Collapse of Deposit Insurance and the Case for Abolition

THE COLLAPSE OF DEPOSIT INSURANCE — AND THE CASE FOR ABOLITION By Richard M. Salsman ECONOMIC EDUCATION BULLETIN Published by AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH Great Barrington, Massachusetts Copyright Richard M. Salsman 1993 About A.I.E.R. MERICAN Institute for Economic Research, founded in 1933, is an independent scientific and educational organization. The A Institute's research is planned to help individuals protect their personal interests and those of the Nation. Tìie industrious and thrifty, those who pay most of the Nation's taxes, must be the principal guardians of American civilization. By publishing the results of scientific inquiry, carried on with diligence, independence, and integrity, American Institute for Economic Research hopes to help those citizens preserve the best of the Nation's heritage and choose wisely the policies that will determine the Nation's future. The Institute represents no fund, concentration of wealth, or other special interests. Advertising is not accepted in its publications. Financial support for the Institute is provided primarily by the small annual fees from several thousand sustaining members, by receipts from sales of its publications, by tax-deductible contributions, and by the earnings of its wholly owned investment advisory organization, American Investment Services, Inc. Experience suggests that information and advice on eco- nomic subjects are most useful when they come from a source that is independent of special interests, either commercial or political. The provisions of the charter and bylaws ensure that neither the Insti- tute itself nor members of its staff may derive profit from organizations or businesses that happen to benefit from the results of Institute research. -

MONEY and the EARLY GREEK MIND: Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy

This page intentionally left blank MONEY AND THE EARLY GREEK MIND How were the Greeks of the sixth century bc able to invent philosophy and tragedy? In this book Richard Seaford argues that a large part of the answer can be found in another momentous development, the invention and rapid spread of coinage, which produced the first ever thoroughly monetised society. By transforming social relations, monetisation contributed to the ideas of the universe as an impersonal system (presocratic philosophy) and of the individual alienated from his own kin and from the gods (in tragedy). Seaford argues that an important precondition for this monetisation was the Greek practice of animal sacrifice, as represented in Homeric epic, which describes a premonetary world on the point of producing money. This book combines social history, economic anthropology, numismatics and the close reading of literary, inscriptional, and philosophical texts. Questioning the origins and shaping force of Greek philosophy, this is a major book with wide appeal. richard seaford is Professor of Greek Literature at the University of Exeter. He is the author of commentaries on Euripides’ Cyclops (1984) and Bacchae (1996) and of Reciprocity and Ritual: Homer and Tragedy in the Developing City-State (1994). MONEY AND THE EARLY GREEK MIND Homer, Philosophy, Tragedy RICHARD SEAFORD cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521832281 © Richard Seaford 2004 This publication is in copyright. -

Xerox University Microfilms 3 0 0North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75 - 21,515

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1 .T h e sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper le ft hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

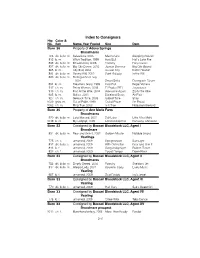

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Name,Year Foaled Sire Dam Barn 36 Property of Adena Springs Broodmares 735 dk. b./br. m. Salvadoria, 2005 Macho Uno Skipping Around 813 b. m. Witch Tradition, 1999 Holy Bull Hall's Lake Fire 833 dk. b./br. m. Beautiful Sky, 2003 Forestry Forty Carats 837 dk. b./br. m. Big City Danse, 2002 Joyeux Danseur Big City Bound 865 b. m. City Bird, 2004 Carson City Eishin Houlton 886 dk. b./br. m. Devine Will, 2002 Saint Ballado In the Will 889 dk. b./br. m. Distinguished Lady, 2004 Smart Strike Distinguish Forum 894 b. m. Dreamers Glory, 1999 Holy Bull Regal Victress 917 ch. m. Feisty Woman, 2003 El Prado (IRE) Joustabout 919 ch. m. First At the Wire, 2004 Awesome Again Zip to the Wire 925 b. m. Galica, 2001 Dixieland Brass Air Flair 927 ch. m. Getback Time, 2003 Gilded Time Shay 1029 gr/ro. m. Out of Pride, 1999 Out of Place I'm Proud 1062 ch. m. Ring True, 2003 Is It True Notjustanotherbird Barn 35 Property of Ann Marie Farm Broodmares 970 dk. b./br. m. Lake Merced, 2001 Salt Lake Little Miss Molly 1019 b. m. My Lollipop, 2005 Lemon Drop Kid Runaway Cherokee Barn 33 Consigned by Baccari Bloodstock LLC, Agent I Broodmare 831 dk. b./br. m. Bear and Grin It, 2002 Golden Missile Notable Sword Yearlings 775 ch. c. unnamed, 2009 Speightstown Surf Light 832 dk. b./br. c. unnamed, 2009 With Distinction Bear and Grin It 846 b. f. unnamed, 2009 Songandaprayer Broken Flower 892 ch. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Long Delayed Echo: New Approach to the Problem

Geometrical joke(r?)s for SETI. R. T. Faizullin OmSTU, Omsk, Russia Since the beginning of radio era long delayed echoes (LDE) were traced. They are the most likely candidates for extraterrestrial communication, the so-called "paradox of Stormer" or "world echo". By LDE we mean a radio signal with a very long delay time and abnormally low energy loss. Unlike the well-known echoes of the delay in 1/7 seconds, the mechanism of which have long been resolved, the delay of radio signals in a second, ten seconds or even minutes is one of the most ancient and intriguing mysteries of physics of the ionosphere. Nowadays it is difficult to imagine that at the beginning of the century any registered echo signal was treated as extraterrestrial communication: “Notable changes occurred at a fixed time and the analogy among the changes and numbers was so clear, that I could not provide any plausible explanation. I'm familiar with natural electrical interference caused by the activity of the Sun, northern lights and telluric currents, but I was sure, as it is possible to be sure in anything, that the interference was not caused by any of common reason. Only after a while it came to me, that the observed interference may occur as the result of conscious activities. I'm overwhelmed by the the feeling, that I may be the first men to hear greetings transmitted from one planet to the other... Despite the signal being weak and unclear it made me certain that soon people, as one, will direct their eyes full of hope and affection towards the sky, overwhelmed by good news: People! We got the message from an unknown and distant planet. -

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis In the spring of 1837, people panicked as financial and economic uncer- tainty spread within and between New York, New Orleans, and London. Although the period of panic would dramatically influence political, cultural, and social history, those who panicked sought to erase from history their experiences of one of America’s worst early financial crises. The Many Panics of 1837 reconstructs the period between March and May 1837 in order to make arguments about the national boundaries of history, the role of information in the economy, the personal and local nature of national and international events, the origins and dissemination of economic ideas, and most importantly, what actually happened in 1837. This riveting transatlantic cultural history, based on archival research on two continents, reveals how people transformed their experiences of financial crisis into the “Panic of 1837,” a single event that would serve as a turning point in American history and an early inspiration for business cycle theory. Jessica M. Lepler is an assistant professor of history at the University of New Hampshire. The Society of American Historians awarded her Brandeis University doctoral dissertation, “1837: Anatomy of a Panic,” the 2008 Allan Nevins Prize. She has been the recipient of a Hench Post-Dissertation Fellowship from the American Antiquarian Society, a Dissertation Fellowship from the Library Company of Philadelphia’s Program in Early American Economy and Society, a John E. Rovensky Dissertation Fellowship in Business History, and a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship from the U.S. -

Bank Liability Insurance Schemes in the United States Before 1865∗

Bank Liability Insurance Schemes in the United States Before 1865∗ Warren E. Weber Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta University of South Carolina May 2014 Abstract Prior to 1861, several U.S. states established bank liability insurance schemes. One type was an insurance fund; another was a mutual guarantee system. Under both, member banks were legally responsible for the liabilities of any insolvent bank. This paper hypothesizes that moral hazard was better controlled the more power and incen- tive member banks had to control other members' risk-taking behavior. Schemes that gave member banks both strong incentives and power controlled moral hazard better than schemes in which one or both features were weak. Empirical evidence on bank failures and losses on assets is roughly consistent with the hypothesis. Keywords: deposit insurance, moral hazard, banknotes JEL: E42, N21 ∗e-mail: [email protected]. This paper was written in large part while the author was at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. I thank Todd Keister, Robert Lucas, Cyril Monnet, Arthur Rolnick, Eu- gene White, Ariel Zetlin-Jones, Ruilin Zhou, and participants at seminars at the Board of Governors, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, and the University of South Carolina for helpful comments. The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta or Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. 1 1. Introduction Moral hazard is inherent in all insurance. Bank liability insurance is not an exception, as our recent financial experience attests. Today, bank deposit liabilities are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), established by the Banking Act of 1933. -

Sydney Is Singularly Fortunate in That, Unlike Other Australian Cities, Its Newspaper History Has Been Well Documented

Two hundred years of Sydney newspapers: A SHORT HISTORY By Victor Isaacs and Rod Kirkpatrick 1 This booklet, Two Hundreds Years of Sydney Newspapers: A Short History, has been produced to mark the bicentenary of publication of the first Australian newspaper, the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, on 5 March 1803 and to provide a souvenir for those attending the Australian Newspaper Press Bicentenary Symposium at the State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, on 1 March 2003. The Australian Newspaper History Group convened the symposium and records it gratitude to the following sponsors: • John Fairfax Holdings Ltd, publisher of Australia’s oldest newspaper, the Sydney Morning Herald • Paper World Pty Ltd, of Melbourne, suppliers of original newspapers from the past • RMIT University’s School of Applied Communication, Melbourne • The Printing Industries Association of Australia • The Graphic Arts Merchants Association of Australia • Rural Press Ltd, the major publisher of regional newspapers throughout Australia • The State Library of New South Wales Printed in February 2003 by Rural Press Ltd, North Richmond, New South Wales, with the assistance of the Printing Industries Association of Australia. 2 Introduction Sydney is singularly fortunate in that, unlike other Australian cities, its newspaper history has been well documented. Hence, most of this short history of Sydney’s newspapers is derived from secondary sources, not from original research. Through the comprehensive listing of relevant books at the end of this booklet, grateful acknowledgement is made to the writers, and especially to Robin Walker, Gavin Souter and Bridget Griffen-Foley whose work has been used extensively. -

New France (Ca

New France (ca. 1600-1770) Trade silver, beaver, eighteenth century Manufactured in Europe and North America for trade with the Native peoples, trade silver came in many forms, including ear bobs, rings, brooches, gorgets, pendants, and animal shapes. According to Adam Shortt,5 the great France, double tournois, 1610 Canadian economic historian, the first regular Originally valued at 2 deniers, the system of exchange in Canada involving Europeans copper “double tournois” was shipped to New France in large quantities during occurred in Tadoussac in the early seventeenth the early 1600s to meet the colony’s century. Here, French traders bartered each year need for low-denomination coins. with the Montagnais people (also known as the Innu), trading weapons, cloth, food, silver items, and tobacco for animal pelts, especially those of the beaver. Because of the risks associated with In 1608, Samuel de Champlain founded transporting gold and silver (specie) across the the first colonial settlement at Quebec on the Atlantic, and to attract and retain fresh supplies of St. Lawrence River. The one universally accepted coin, coins were given a higher value in the French medium of exchange in the infant colony naturally colonies in Canada than in France. In 1664, became the beaver pelt, although wheat and moose this premium was set at one-eighth but was skins were also employed as legal tender. As the subsequently increased. In 1680, monnoye du pays colony expanded, and its economic and financial was given a value one-third higher than monnoye needs became more complex, coins from France de France, a valuation that held until 1717 when the came to be widely used.