Xerox University Microfilms 3 0 0North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75 - 21,515

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To the Franklin Pierce Papers

INDEX TO THE Franklin Pierce Papers THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS • PRESIDENTS' PAPERS INDEX SERIES INDEX TO THE Franklin Pierce Papers MANUSCRIPT DIVISION • REFERENCE DEPARTMENT LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON: 1962 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 60-60077 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. - Price 25 cents Preface THIS INDEX to the Franklin Pierce Papers is a direct result of the wish of the Congress and the President, as expressed by Public Law 85-147 of August 16,1957, and amended by Public Law 87-263 dated September 21,1961, to arrange, micro film, and index the papers of the Presidents in the Library of Congress in order "to preserve their contents against destruction by \'.'ar or other calamity," to make the Pierce and other Presidential Papers more "readily available for study and research," and to inspire informed patriotism. An appropriation to carry out the provision of the law was approved on July 31, 1958, and actual operations began on August 25. The microfilm of the Pierce Papers became available in 1960. Positive copies of the film may be purchased from the Chief, Photoduplication Service, Library of Congress, \Vashington 25, D.C. A positive print is available for interlibrary loan through the Chief, Loan Division, Library of Congress. Contents Introduction PAGE Provenance . V Selected Bibliography vi How to Use This Index vi Reel List viii A b brevia tions viii Index The Index 1 Appendices National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections card 14 Description of the Papers 15 Sources of Acquisition 15 Statement of the Librarian of Congress 16 III Introduction Provenance These surviving Pierce Papers represent but a small part of \vhat must have existed when Pierce left the E\V HAMPSHIRE \vas silent for half a \Vhite House. -

Martin Van Buren: the Greatest American President

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President —————— ✦ —————— JEFFREY ROGERS HUMMEL resident Martin Van Buren does not usually receive high marks from histori- ans. Born of humble Dutch ancestry in December 1782 in the small, upstate PNew York village of Kinderhook, Van Buren gained admittance to the bar in 1803 without benefit of higher education. Building on a successful country legal practice, he became one of the Empire State’s most influential and prominent politi- cians while the state was surging ahead as the country’s wealthiest and most populous. -

The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1966 The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777 Bernard Mason State University of New York at Binghamton Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Mason, Bernard, "The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777" (1966). United States History. 66. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/66 The 'l(qpd to Independence This page intentionally left blank THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE The 'R!_,volutionary ~ovement in :J{£w rork, 1773-1777~ By BERNARD MASON University of Kentucky Press-Lexington 1966 Copyright © 1967 UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS) LEXINGTON FoR PERMISSION to quote material from the books noted below, the author is grateful to these publishers: Charles Scribner's Sons, for Father Knickerbocker Rebels by Thomas J. Wertenbaker. Copyright 1948 by Charles Scribner's Sons. The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., for John Jay by Frank Monaghan. Copyright 1935 by the Bobbs-Merrill Com pany, Inc., renewed 1962 by Frank Monaghan. The Regents of the University of Wisconsin, for The History of Political Parties in the Province of New York J 17 60- 1776) by Carl L. Becker, published by the University of Wisconsin Press. Copyright 1909 by the Regents of the University of Wisconsin. -

The Collapse of Deposit Insurance and the Case for Abolition

THE COLLAPSE OF DEPOSIT INSURANCE — AND THE CASE FOR ABOLITION By Richard M. Salsman ECONOMIC EDUCATION BULLETIN Published by AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH Great Barrington, Massachusetts Copyright Richard M. Salsman 1993 About A.I.E.R. MERICAN Institute for Economic Research, founded in 1933, is an independent scientific and educational organization. The A Institute's research is planned to help individuals protect their personal interests and those of the Nation. Tìie industrious and thrifty, those who pay most of the Nation's taxes, must be the principal guardians of American civilization. By publishing the results of scientific inquiry, carried on with diligence, independence, and integrity, American Institute for Economic Research hopes to help those citizens preserve the best of the Nation's heritage and choose wisely the policies that will determine the Nation's future. The Institute represents no fund, concentration of wealth, or other special interests. Advertising is not accepted in its publications. Financial support for the Institute is provided primarily by the small annual fees from several thousand sustaining members, by receipts from sales of its publications, by tax-deductible contributions, and by the earnings of its wholly owned investment advisory organization, American Investment Services, Inc. Experience suggests that information and advice on eco- nomic subjects are most useful when they come from a source that is independent of special interests, either commercial or political. The provisions of the charter and bylaws ensure that neither the Insti- tute itself nor members of its staff may derive profit from organizations or businesses that happen to benefit from the results of Institute research. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

The Albany Rural Cemetery

<^ » " " .-^ v^'*^ •V,^'% rf>. .<^ 0- ^'' '^.. , "^^^v ^^^os. l.\''' -^^ ^ ./ > ••% '^.-v- .«-<.. ^""^^^ A o. V V V % s^ •;• A. O /"t. ^°V: 9." O •^^ ' » » o ,o'5 <f \/ ^-i^o ^^'\ .' A. Wo ^ : -^^\ °'yi^^ /^\ ^%|^/ ^'%> ^^^^^^ ^0 v^ 4 o .^'' <^. .<<, .>^. A. c /°- • \ » ' ^> V -•'. -^^ ^^ 'V • \ ^^ * vP Si •T'V %^ "<? ,-% .^^ ^0^ ^^n< ' < o ^X. ' vv-ir- •.-.-., ' •0/ ^- .0-' „f / ^^. V ^ A^ »r^. .. -H rr. .^-^ -^ :'0m^', .^ /<g$S])Y^ -^ J-' /. ^V .;••--.-._.-- %^c^ -"-,'1. OV -^^ < o vP b t'' ^., .^ A^ ^ «.^- A ^^. «V^ ,*^ .J." "-^U-o^ =^ -I o >l-' .0^ o. v^' ./ ^^V^^^.'^ -is'- v-^^. •^' <' <', •^ "°o S .^"^ M 'V;/^ • =.«' '•.^- St, ^0 "V, <J,^ °t. A° M -^j' * c" yO V, ' ', '^-^ o^ - iO -7-, .V -^^0^ o > .0- '#-^ / ^^ ' Why seek ye the living among the dead }"—Luke xxiv : s. [By i)ormission of Erastus Dow Palmer.] e»w <:3~- -^^ THE ALBANY RURAL ^ CEMETERY ITS F A3Ts^ 5tw copies printeil from type Copyn.y:ht. 1S92 Bv HKNkv 1*. PiiKi.rs l*lioto>;raphy by l*iiic MarPoiiaUl, Albany Typogrnpliy and Prcsswork by Brnndow l^rintinj; Comimny, Albany ac:knowledgments. rlfIS hook is tlir D/i/i^mio/fi of a proposilioii on lite pari ot the Iriixtccx to piihlisli a brief liislorv of the .llhaiiy Cemetery A ssoeiation, iiieliidiiiQa report of the eonseeration oration, poem and other exercises. It li'as snoocsted that it niioht be well to attempt son/e- thino- more worthy of the object than a mere pamphlet, and this has been done with a result that must spealc for itself. Jl'h/le it would be impi-aclicable to mention here all who have kindly aided in the zvork, the author desi/'cs to express his particular oblioations : To Mr. -

The U.S. Customs Service: a Bicentennials History

1 1 I ROOM Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Prince, Carl E. The U.S. Customs Service: a bicentennial history/Carl E. Prince and Mollie Keller. p. cm. Includes index. 1. U.S. Customs Service— History. I. Keller, Mollie. II. Title. HJ6622.A6 1989 353.0072'46'09—dc20 89-600730 ISBN 0-9622904-0-8 PREFACE When we began the research for this book, the sources appeared daunting: the customs records in the National Archives alone measured 8,000 linear feet. There are more customs records among the Treasury Department's papers and other collections. Thousands more linear feet are located at the regional federal records centers across the United States. Every major research library houses collections rich in customs history as well, and innumerable histo- rians for nearly 200 years have written about the Customs Service or touched on it in their extended studies. Knowing that we could not possibly exhaust existing primary sources in one year of research (or 20), we chose a policy of sampling the richest primary sources, many of them obscure and little used because they lie buried amid poorly catalogued or uncatalogued collections. We hoped by this means to provide a small path for others to follow; customs records, like the Customs Service itself, are rich not only in American economic and political history, but social and cultural history as well. This study is intended to reflect that variety. We also realized that a one-volume study could at best provide only a superficial chronicling of Customs' myriad involvement in the nation's history, so we chose to discuss in some depth representative topics —pressure points like the Amer- ican Revolution, the embargo era, the nullification controversy, the Civil War, Prohibition, and drug enforcement. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis In the spring of 1837, people panicked as financial and economic uncer- tainty spread within and between New York, New Orleans, and London. Although the period of panic would dramatically influence political, cultural, and social history, those who panicked sought to erase from history their experiences of one of America’s worst early financial crises. The Many Panics of 1837 reconstructs the period between March and May 1837 in order to make arguments about the national boundaries of history, the role of information in the economy, the personal and local nature of national and international events, the origins and dissemination of economic ideas, and most importantly, what actually happened in 1837. This riveting transatlantic cultural history, based on archival research on two continents, reveals how people transformed their experiences of financial crisis into the “Panic of 1837,” a single event that would serve as a turning point in American history and an early inspiration for business cycle theory. Jessica M. Lepler is an assistant professor of history at the University of New Hampshire. The Society of American Historians awarded her Brandeis University doctoral dissertation, “1837: Anatomy of a Panic,” the 2008 Allan Nevins Prize. She has been the recipient of a Hench Post-Dissertation Fellowship from the American Antiquarian Society, a Dissertation Fellowship from the Library Company of Philadelphia’s Program in Early American Economy and Society, a John E. Rovensky Dissertation Fellowship in Business History, and a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship from the U.S. -

Bank Liability Insurance Schemes in the United States Before 1865∗

Bank Liability Insurance Schemes in the United States Before 1865∗ Warren E. Weber Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta University of South Carolina May 2014 Abstract Prior to 1861, several U.S. states established bank liability insurance schemes. One type was an insurance fund; another was a mutual guarantee system. Under both, member banks were legally responsible for the liabilities of any insolvent bank. This paper hypothesizes that moral hazard was better controlled the more power and incen- tive member banks had to control other members' risk-taking behavior. Schemes that gave member banks both strong incentives and power controlled moral hazard better than schemes in which one or both features were weak. Empirical evidence on bank failures and losses on assets is roughly consistent with the hypothesis. Keywords: deposit insurance, moral hazard, banknotes JEL: E42, N21 ∗e-mail: [email protected]. This paper was written in large part while the author was at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. I thank Todd Keister, Robert Lucas, Cyril Monnet, Arthur Rolnick, Eu- gene White, Ariel Zetlin-Jones, Ruilin Zhou, and participants at seminars at the Board of Governors, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, and the University of South Carolina for helpful comments. The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta or Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. 1 1. Introduction Moral hazard is inherent in all insurance. Bank liability insurance is not an exception, as our recent financial experience attests. Today, bank deposit liabilities are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), established by the Banking Act of 1933. -

Filling Vacancies in the Office of Lieutenant Governor

MAY 2009 CITIZENS UNION | ISSUE BRIEF AND POSITION STATEMENT Filling Vacancies in the Office of Lieutenant Governor INTRODUCTION Citizens Union of the City of Shortly after Citizens Union’s last report on the subject of filling vacancies in February 2008, New York is an independent, former Governor Eliot Spitzer resigned from the office of governor and former Lieutenant non-partisan civic organization of Governor David A. Paterson assumed the role of New York’s fifty-fifth governor. Although the members dedicated to promoting good government and political reform in the voters elected Paterson as lieutenant governor in 2006, purposefully to fill such a vacancy in the city and state of New York. For more office of governor should it occur, his succession created a vacancy in the office of lieutenant than a century, Citizens Union has governor, and, more importantly, created confusion among citizens and elected officials in served as a watchdog for the public Albany about whether the current Temporary President of the Senate who serves as acting interest and an advocate for the Lieutenant Governor can serve in both positions simultaneously. This unexpected vacancy common good. Founded in 1897 to fight the corruption of Tammany Hall, exposed a deficiency in the law because no process exists to fill permanently a vacancy in the Citizens Union currently works to position of lieutenant governor until the next statewide election in 2010. ensure fair elections, clean campaigns, and open, effective government that is Though the processes for filling vacancies ordinarily receive little attention, the recent number accountable to the citizens of New of vacancies in various offices at the state and local level has increased the public’s interest in York. -

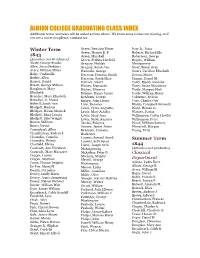

ALBION COLLEGE GRADUATING CLASS INDEX Additional Terms and Years Will Be Added As Time Allows

ALBION COLLEGE GRADUATING CLASS INDEX Additional terms and years will be added as time allows. We know some names are missing, so if you see a correction please, contact us. Winter Term Green, Denslow Elmer Pray Jr., Isaac Green, Harriet E. F. Roberts, Richard Ely 1843 Green, Marshall Robertson, George [Attendees not Graduates] Green, Perkins Hatfield Rogers, William Alcott, George Brooks Gregory, Huldah Montgomery Allen, Amos Stebbins Gregory, Sarah Ann Stout, Byron Gray Avery, William Miller Hannahs, George Stuart, Caroline Elizabeth Baley, Cinderella Harroun, Denison Smith Sutton, Moses Barker, Ellen Harroun, Sarah Eliza Timms, Daniel M. Barney, Daniel Herrick, Albert Torry, Ripley Alcander Basset, George Stillson Hickey, Manasseh Torry, Susan Woodbury Baughman, Mary Hickey, Minerva Tuttle, Marquis Hull Elizabeth Holmes, Henry James Tuttle, William Henry Benedict, Mary Elizabeth Ketchum, George Volentine, Nelson Benedict, Jr, Moses Knapp, John Henry Vose, Charles Otis Bidwell, Sarah Ann Lake, Dessoles Waldo, Campbell Griswold Blodgett, Hudson Lewis, Cyrus Augustus Ward, Heman G. Blodgett, Hiram Merrick Lewis, Mary Athalia Warner, Darius Blodgett, Mary Louisa Lewis, Mary Jane Williamson, Calvin Hawley Blodgett, Silas Wright Lewis, Sarah Augusta Williamson, Peter Brown, William Jacobs, Rebecca Wood, William Somers Burns, David Joomis, James Joline Woodruff, Morgan Carmichael, Allen Ketchum, Cornelia Young, Urial Chamberlain, Roderick Rochester Champlin, Cornelia Loomis, Samuel Sured Summer Term Champlin, Nelson Loomis, Seth Sured Chatfield, Elvina Lucas, Joseph Orin 1844 Coonradt, Ann Elizabeth Mahaigeosing [Attendees not graduates] Coonradt, Mary Margaret McArthur, Peter D. Classical Cragan, Louisa Mechem, Stanley Cragan, Matthew Merrill, George Department Crane, Horace Delphin Washington Adkins, Lydia Flora De Puy, Maria H. Messer, Lydia Allcott, George B.