Schematic Vs. Topographic Maps in Pedestrian Navigation: How Much Map Detail Is Necessary to Support Wayfinding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 4–How to Read a Topographic Map

Lesson 4–How to Read a Topographic Map Key teaching points Suggestions for teaching Ask students to answer these ques- this lesson (3, 35-minute sessions) tions and fill in their answers on A topographic map is a representa- Activity Sheet #4: tion of a three-dimensional surface on On the poster is a topographic map a flat piece of paper. The digital eleva- of Salt Lake City. This lesson will help Which is higher, hill A or hill B? tion model on the poster is helpful in students learn how to read that map. (Answer: hill B) understanding topographic maps. Learning to use a topographic map is a difficult skill, because it requires stu- Which is steeper, hill A or hill B? Contour lines, sometimes called "level dents to visualize a three-dimensional (Answer: hill B) lines," join points of equal elevation. surface from a flat piece of paper. The closer together the contour lines Students need both practice and imag- 3. Compare a topographic map to a picture of the same place. Now have appear on a topographic map, the ination to learn to visualize hills and steeper the slope (assuming constant valleys from the contour lines on a the students look at the topographic of the same two hills. Say, "The contour intervals). topographic map. map lines you see on this map are called contour lines. Can you see why they Topographic maps have a variety of A digital terrain model of Salt Lake City uses, from planning the best route for is shown on the poster. -

Survey of India Department of Science & Technology Rashtriya Manchitran Niti NATIONAL MAP POLICY 1

Survey of India Department of Science & Technology Rashtriya Manchitran Niti NATIONAL MAP POLICY 1. PREAMBLE All socio-economic developmental activities, conservation of natural resources, planning for disaster mitigation and infrastructure development require high quality spatial data. The advancements in digital technologies have now made it possible to use diverse spatial databases in an integrated manner. The responsibility for producing, maintaining and disseminating the topographic map database of the whole country, which is the foundation of all spatial data vests with the Survey of India (SOI). Recently, SOI has been mandated to take a leadership role in liberalizing access of spatial data to user groups without jeopardizing national security. To perform this role, the policy on dissemination of maps and spatial data needs to be clearly stated. 2. OBJECTIVES • To provide, maintain and allow access and make available the National Topographic Database (NTDB) of the SOI conforming to national standards. • To promote the use of geospatial knowledge and intelligence through partnerships and other mechanisms by all sections of the society and work towards a knowledge-based society. 3. TWO SERIES OF MAPS To ensure that in the furtherance of this policy, national security objectives are fully safeguarded, it has been decided that there will be two series of maps namely (a) Defence Series Maps (DSMs)- These will be the topographical maps (on Everest/WGS-84 Datum and Polyconic/UTM Projection) on various scales (with heights, contours and full content without dilution of accuracy). These will mainly cater for defence and national security requirements. This series of maps (in analogue or digital forms) for the entire country will be classified, as appropriate, and the guidelines regarding their use will be formulated by the Ministry of Defence. -

US Topo Map Users Guide

US Topo Map Users Guide April 2018. Based on Adobe Reader XI version 11.0.20 (Minor updates and corrections, November 2017.) April 2018 Updates Based on Adobe Reader DC version 2018.009.20050 In 2017, US Topo production systems were redesigned. This system change has few impacts on the design and appearance of US Topo maps, but does affect the geospatial characteristics. The previous version of this Users Guide is frozen in its current form, and applies to US Topo maps created The previous version of this Users Guide, which before approximately June 2017 and to all HTMC applies to US Topo maps created before June maps. The document you are now reading applies 2017 and to all HTMC maps, is linked from to US Topo maps created after June 2017, and https://nationalmap.gov/ustopo will be maintained into the future. US Topo maps are the current generation of USGS topographic maps. The first of these maps were published in 2009. They are modeled on the legacy 7.5-minute series of the mid-20th century, but unlike traditional topographic maps they are mass produced from GIS databases, and are published as PDF documents instead of as paper maps. US Topo maps include base data from The National Map and other sources, including roads, hydrography, contours, boundaries, woodland cover, structures, geographic names, an aerial photo image, Federal land boundaries, and shaded relief. For more information see the project web page at https://nationalmap.gov/ustopo. The Historical Topographic Map Collection (HTMC) includes all editions and all scales of USGS standard topographic quadrangle maps originally published as paper maps in the period 1884-2006. -

Chapter 13.2: Topographic Maps 1

Chapter 13.2: Topographic Maps 1 A map is a model or representation of objects and terrain in the actual environment. There are numerous types of maps. Some of the types of maps include mental, planimetric, topographic, and even treasure maps. The concept of mapping was introduced in the section using natural features. Maps are created for numerous purposes. A treasure map is used to find the buried treasure. Topographic maps were originally used for military purposes. Today, they have been used for planning and recreational purposes. Although other types of maps are mentioned, the primary focus of this section is on topographic maps. Types of Maps Mental Maps – The mind makes mental maps all the time. You drive to the grocery store. You turn right onto the boulevard. You identify a street sign, building or other landmark and know where this is where you turn. You have made a mental map. This was discussed under using natural features. Planimetric Maps – A planimetric map is a two dimensional representation of objects in the environment. Generally, planimetric maps do not include topographic representation. Road maps, Rand McNally ® and GoogleMaps ® (not GoogleEarth) are examples of planimetric maps. Topographic Maps – Topographic maps show elevation or three-dimensional topography two dimensionally. Topographic maps use contour lines to show elevation. A chart refers to a nautical chart. Nautical charts are topographic maps in reverse. Rather than giving elevation, they provide equal levels of water depth. Topographic Maps Topographic maps show elevation or three-dimensional topography two dimensionally. Topographic maps use contour lines to show elevation. -

(GIS)-Based Approach to Derivative Map Production and Visualizing Bedrock Topography Within the Town of Rutland, Vermont, USA

ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2014, 3, 130-142; doi:10.3390/ijgi3010130 OPEN ACCESS ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information ISSN 2220-9964 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijgi/ Article A Geographic Information Systems (GIS)-Based Approach to Derivative Map Production and Visualizing Bedrock Topography within the Town of Rutland, Vermont, USA John G. Van Hoesen Department of Environmental Studies, Green Mountain College, One Brennan Circle, Poultney, VT 05764, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-802-287-8387; Fax: +1-802-287-8080 Received: 17 December 2013; in revised form: 21 January 2014 / Accepted: 22 January 2014 / Published: 29 January 2014 Abstract: Many state and national geological surveys produce map products from surficial and bedrock geologic maps as a value-added deliverable for a variety of stakeholders. Improvements in powerful geostatistical exploratory tools and robust three-dimensional capabilities within geographic information systems (GIS) can facilitate the production of derivative products. In addition to providing access to geostatistical functions, many software packages are also capable of rendering three-dimensional visualizations using spatially distributed point data. A GIS-based approach using ESRI’s® Geostatistical Analyst® was used to create derivative maps depicting surficial overburden, bedrock topography, and potentiometric surface using well data and bedrock exposures. This methodology describes the importance and relevance of creating three-dimensional visualizations in tandem with traditional two-dimensional map products. These 3D products are especially useful for town managers and planners—often unfamiliar with interpreting two-dimensional geologic map products—so they can better visualize and understand the relationships between surficial overburden and potential groundwater resources. -

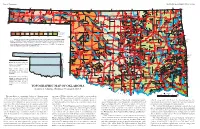

TOPOGRAPHIC MAP of OKLAHOMA Kenneth S

Page 2, Topographic EDUCATIONAL PUBLICATION 9: 2008 Contour lines (in feet) are generalized from U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps (scale, 1:250,000). Principal meridians and base lines (dotted black lines) are references for subdividing land into sections, townships, and ranges. Spot elevations ( feet) are given for select geographic features from detailed topographic maps (scale, 1:24,000). The geographic center of Oklahoma is just north of Oklahoma City. Dimensions of Oklahoma Distances: shown in miles (and kilometers), calculated by Myers and Vosburg (1964). Area: 69,919 square miles (181,090 square kilometers), or 44,748,000 acres (18,109,000 hectares). Geographic Center of Okla- homa: the point, just north of Oklahoma City, where you could “balance” the State, if it were completely flat (see topographic map). TOPOGRAPHIC MAP OF OKLAHOMA Kenneth S. Johnson, Oklahoma Geological Survey This map shows the topographic features of Oklahoma using tain ranges (Wichita, Arbuckle, and Ouachita) occur in southern contour lines, or lines of equal elevation above sea level. The high- Oklahoma, although mountainous and hilly areas exist in other parts est elevation (4,973 ft) in Oklahoma is on Black Mesa, in the north- of the State. The map on page 8 shows the geomorphic provinces The Ouachita (pronounced “Wa-she-tah”) Mountains in south- 2,568 ft, rising about 2,000 ft above the surrounding plains. The west corner of the Panhandle; the lowest elevation (287 ft) is where of Oklahoma and describes many of the geographic features men- eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas is a curved belt of forested largest mountainous area in the region is the Sans Bois Mountains, Little River flows into Arkansas, near the southeast corner of the tioned below. -

What's Your Theory of Effective Schematic Map Design?

What’s Your Theory of Effective Schematic Map Design? Maxwell. J. Roberts Department of Psychology University of Essex Colchester, UK [email protected] Abstract—Amongst designers, researchers, and the general general public accept or reject radical new creations. public, there exists a diverse array of opinion about good practice Furthermore, the lay-theories held by designers will affect the in schematic map design, and a lack of awareness that such products that they create and the recommendations that they opinions are not necessarily universally held nor supported by make. Similarly, the lay-theories of transport managers will evidence. This paper gives an overview of the range of opinion determine design specifications and the acceptance or rejection that can be encountered, the consequences that this has for of end-products. With so many different theories in circulation, published designs, and a framework for organising the various conflicts will be inevitable, hence the polarised response to the views. controversial Madrid Metro map of 2007, which generated a huge adverse reaction amongst residents: presumably, the Keywords—schematic mapping; lay-theories, expectations and transport authority believed that this was a sound design. prejudices; effective design; cognition; intelligence. Likewise, the adverse public response to the removal of the I. LAY-THEORIES OF DESIGN River Thames from the London Underground map in 2009. The lay-theory held by officials, presumably, was that the river Whenever I create a controversial new schematic map and was irrelevant to usability. The public disagreed, and the river publish it on the internet, the diversity of opinion that it evokes returned a few months later. -

Module 4 Electronic Diagrams and Schematics

ENGINEERING SYMBOLOGY, PRINTS, AND DRAWINGS Module 4 Electronic Diagrams and Schematics Engineering Symbology, Prints, & Drawings Electronic Diagrams & Schematics TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Co nte nts TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................... i LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................ii LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ iii REFERENCES ................................................................................................................iv OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................. 1 ELECTRONIC DIAGRAMS, PRINTS, AND SCHEMATICS ............................................ 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 Electronic Schematic Drawing Symbology .................................................................. 3 Examples of Electronic Schematic Diagrams .............................................................. 6 Reading Electronic Prints, Diagrams and Schematics ................................................. 8 Block Drawing Symbology ......................................................................................... 13 Examples of Block Diagrams .................................................................................... -

49 Chapter 5 Topographical Maps

Topographical Maps Chapter 5 Topographical Maps You know that the map is an important geographic tool. You also know that maps are classified on the basis of scale and functions. The topographical maps, which have been referred to in Chapter 1 are of utmost importance to geographers. They serve the purpose of base maps and are used to draw all the other maps. Topographical maps, also known as general purpose maps, are drawn at relatively large scales. These maps show important natural and cultural features such as relief, vegetation, water bodies, cultivated land, settlements, and transportation networks, etc. These maps are prepared and published by the National Mapping Organisation of each country. For example, the Survey of India prepares the topographical maps in India for the entire country. The topographical maps are drawn in the form of series of maps at different scales. Hence, in the given series, all maps employ the same reference point, scale, projection, conventional signs, symbols and colours. The topographical maps in India are prepared in two series, i.e. India and Adjacent Countries Series and The International Map Series of the World. India and Adjacent Countries Series: Topographical maps under India and Adjacent Countries Series were prepared by the Survey of India till the coming into existence of Delhi Survey Conference in 1937. Henceforth, the preparation of maps for the adjoining 49 countries was abandoned and the Survey of India confined itself to prepare and publish the topographical maps for India as per the specifications laid down for the International Map Series of the World. -

Numbering System 0F Topographical Maps by Prof. Subhas Manna, Department of Geography, Narajole Raj College

Numbering System 0f Topographical Maps by Prof. Subhas Manna, Department of Geography, Narajole Raj College Topographic maps are an essential part of the field of geology due to the comprehensive analysis of a particular surface. Students can explore more about the topographic map here. Definition and Meaning of Topographic Map A topographic map is a map that represents the locations of geographical features. Furthermore, these geographical features can be mountains, valleys, plain surfaces, water bodies and many more. Topographic maps refer to maps at large and medium scales that incorporate a massive variety of information. All the components of topographic maps carry equal importance. Topographic maps refer to a graphical representation of the three-dimensional configuration of the surface of the Earth. Moreover, such maps show the size, shape, and distribution of landscape features. Also, such maps present the vertical and horizontal positions of those features whose representations take place. Most noteworthy makes use of contour lines so as to show different elevations on a map. Structure of Topographic Map Topographic maps have a detailed and compendious structure. The various aspects of a topographic map can be divided into three major groups: Relief: The depiction of the relief aspect is with brown contour lines that represent the mountains, hills, valleys, plains, etc. The elevations are available in meters (or feet) above the mean sea level. Furthermore, there are also spot elevations are shown in the black colour. Moreover, in these spot elevations, the marking of the lake level, the summit of a hill, or the road intersections takes place for the purpose of elevation. -

Vision & Implementation Plan

Buffalo River Greenway Vision & Implementation Plan Implementation Guidelines for the Buffalo River, Cayuga Creek, Buffalo Creek and Cazenovia Creek within the City of Buffalo and Towns of Cheektowaga and West Seneca. Prepared For: Buffalo Niagara RIVERKEEPER® Prepared By: Lynn Mason, ASLA With Assistance From: Julie Barrett O’Neill Jill Spisiak Jedlicka Lynda Schneekloth May 2006 II TABLE OF CONTENTS FIGURE LIST pg. IV INVOLVED AGENCIES pg. VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY pg. VII I. GREENWAY VISION pg. 1 1. Greenway Benefits pg. 3 2. Buffalo River Greenway Project Area pg. 8 II. GREENWAY PLANNING HISTORY pg. 15 1. Recent Projects pg. 17 2. Recent Planning Projects pg. 28 III. EXISTING GREENWAY RESOURCES pg. 29 1. Parks & Parkways pg. 31 2. Conservation Areas pg. 37 3. Bike/Hike Trails pg. 38 4. Boat Launches and Marinas pg. 41 5. Fishing Access and Hot Spots pg. 41 6. Urban Canoe Trail and Launches pg. 42 7. Heritage Interpretation Areas pg. 44 IV. PROPOSED NEW GREENWAY ELEMENTS pg. 47 1. Introduction pg. 49 2. Buffalo River Trail Segments pg. 56 3. Site Specific Opportunities pg. 58 V. IMPLEMENTATION pg. 95 1. Introduction pg. 97 2. Implementation Strategies pg. 106 3. Leveraging Resources and Identifying Funding pg. 108 4. Legislative Action pg. 110 5. Education and Encouragement pg. 110 6. Operations and Maintenance pg. 111 7. Trail Development pg. 112 8. Design Guidelines pg. 181 APPENDIX/ BACKGROUND INFORMATION pg. 189 A. Existing Greenway Resources pg. 191 B. Prohibited Uses pg. 209 C. Phytoremediation pg. 213 D. Buffalo River Paper Streets: A Status Report pg. 215 REFERENCES pg. -

How Neurons Exploit Fractal Geometry to Optimize Their Network Connectivity Julian H

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN How neurons exploit fractal geometry to optimize their network connectivity Julian H. Smith1,5, Conor Rowland1,5, B. Harland2, S. Moslehi1, R. D. Montgomery1, K. Schobert1, W. J. Watterson1, J. Dalrymple‑Alford3,4 & R. P. Taylor1* We investigate the degree to which neurons are fractal, the origin of this fractality, and its impact on functionality. By analyzing three‑dimensional images of rat neurons, we show the way their dendrites fork and weave through space is unexpectedly important for generating fractal‑like behavior well‑ described by an ‘efective’ fractal dimension D. This discovery motivated us to create distorted neuron models by modifying the dendritic patterns, so generating neurons across wide ranges of D extending beyond their natural values. By charting the D‑dependent variations in inter‑neuron connectivity along with the associated costs, we propose that their D values refect a network cooperation that optimizes these constraints. We discuss the implications for healthy and pathological neurons, and for connecting neurons to medical implants. Our automated approach also facilitates insights relating form and function, applicable to individual neurons and their networks, providing a crucial tool for addressing massive data collection projects (e.g. connectomes). Many of nature’s fractal objects beneft from the favorable functionality that results from their pattern repeti- tion at multiple scales 1–3. Anatomical examples include cardiovascular and respiratory systems4 such as the bronchial tree5 while examples from natural scenery include coastlines 6, lightning7, rivers8, and trees9,10. Along with trees, neurons are considered to be a prevalent form of fractal branching behavior11.