Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Although a Quality Text Will Explore Universal Human Concerns, All Texts

Although a quality text will explore universal human concerns, all texts are fundamentally influenced by the values of the respective composer’s context, and therefore will not easily transcend time without the act of appropriation. Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest, has enduring value as it both reflects and criticises the standard perspectives of his Jacobean era. Margaret Atwood has effectively appropriated this text within her novel, Hag-Seed, by adapting Shakespeare’s concerns to a modern era and utilising it to critique her own societies context. Atwood transposes the exploration of the treatment of marginalised people from the ostracised figure of Caliban to the disadvantaged group of prisoners that Felix seeks to direct. She also translates Shakespeare’s temporal commentary of gender roles within the patriarchal society of 17th century England as depicted through Miranda, into the feminist character of Anne-Marie. Finally, Atwood has reflected the provocative discoveries made by Prospero, as he experienced a reassessment of previous perspectives in order to evaluate new perceptions, through Felix, who undergoes a similar transformation of self. In this respect, Atwood’s text transcends time through effectively becoming a portal which draws values from the Jacobean era and translates them so that modern audiences can reflect on themselves and their society. PARAGRAPH 1: Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest, explores the colonial expansion that took place during the 17th century and the vexed relationship between the ‘explorers’ and the indigenous, as the impacts of colonialization began to permeate the common beliefs of society. The negative insinuations associated with indigenous groups becomes evident within the text when Prospero, the embodiment of European colonisation, uses a zoomorphic description of Caliban to present him as a creature less than human, “not honoured with human shape” in which Shakespeare satirizes the ethnocentric view of white ‘explorers’. -

The Trouble with Bibliographies

This article was downloaded by: [University of Hawaii at Manoa] On: 25 April 2012, At: 17:37 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Slavic & East European Information Resources Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wsee20 The Trouble With Bibliographies: Where Is Mezhov When You Need Him? Patricia Polansky a a Hamilton Library, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA Available online: 12 Mar 2012 To cite this article: Patricia Polansky (2012): The Trouble With Bibliographies: Where Is Mezhov When You Need Him?, Slavic & East European Information Resources, 13:1, 26-72 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15228886.2012.651197 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

Feature Films

MARCELO ZARVOS AWARDS/NOMINATIONS CINEMA BRAZIL GRAND PRIZE FLORES RARAS NOMINATION (2014) Best Original Music ONLINE FILM & TELEVISION PHIL SPECTOR ASSOCIATION AWARD NOMINATION (2013) Best Music in a Non-Series BLACK REEL AWARDS BROOKLYN’S FINEST NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score EMMY AWARD NOMINATION YOU DON’T KNOW JACK (2010) Music Composition For A Miniseries, Movie or Special (Dramatic Underscore) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION TAKING CHANCE (2009) Music Composition For A Miniseries, Movie or Special (Dramatic Underscore) BRAZILIA FESTIVAL OF UMA HISTÓRIA DE FUTEBOL BRAZILIAN CINEMA AWARD (1998) 35mm Shorts- Best Music FEATURE FILMS MAPPLETHORPE Eliza Dushku, Nate Dushku, Ondi Timoner, Richard J. Interloper Films Bosner, prods. Ondi Timoner, dir. THE CHAPERONE Kelly Carmichael, Rose Ganguzza, Elizabeth McGovern, Anonymous Content Gary Hamilton, prods. Michael Engler, dir. BEST OF ENEMIES Tobey Maguire, Matt Berenson, Matthew Plouffe, Danny Netflix / Likely Story Strong, prods. Robin Bissell, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 MARCELO ZARVOS LAND OF STEADY HABITS Nicole Holofcener, Anthony Bregman, Stefanie Azpiazu, Netflix / Likely Story prods. Nicole Holofcener, dir. WONDER David Hoberman, Todd Lieberman, prods. Lionsgate Stephen Chbosky, dir. FENCES Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington, prods. Paramount Pictures Denzel Washington, dir. ROCK THE KASBAH Steve Bing, Bill Block, Mitch Glazer, Jacob Pechenik, Open Road Films Ethan Smith, prods. Barry Levinson, dir. OUR KIND OF TRAITOR Simon Cornwell, Stephen Cornwell, Gail Egan, prods. The Ink Factory Susanna White, dir. AMERICAN ULTRA David Alpert, Anthony Bregman, Kevin Scott Frakes, Lionsgate Britton Rizzio, prods. Nima Nourizadeh, dir. THE CHOICE Theresa Park, Peter Safran, Nicholas Sparks, prods. Lionsgate Ross Katz, dir. CELL Michael Benaroya, Shara Kay, Richard Saperstein, Brian Benaroya Pictures Witten, prods. -

(XXXIII: 11) Brian De Palma: the UNTOUCHABLES (1987), 119 Min

November 8, 2016 (XXXIII: 11) Brian De Palma: THE UNTOUCHABLES (1987), 119 min. (The online version of this handout has color images and hot url links.) DIRECTED BY Brian De Palma WRITING CREDITS David Mamet (written by), Oscar Fraley & Eliot Ness (suggested by book) PRODUCED BY Art Linson MUSIC Ennio Morricone CINEMATOGRAPHY Stephen H. Burum FILM EDITING Gerald B. Greenberg and Bill Pankow Kevin Costner…Eliot Ness Sean Connery…Jimmy Malone Charles Martin Smith…Oscar Wallace Andy García…George Stone/Giuseppe Petri Robert De Niro…Al Capone Patricia Clarkson…Catherine Ness Billy Drago…Frank Nitti Richard Bradford…Chief Mike Dorsett earning Oscar nominations for the two lead females, Piper Jack Kehoe…Walter Payne Laurie and Sissy Spacek. His next major success was the Brad Sullivan…George controversial, ultra-violent film Scarface (1983). Written Clifton James…District Attorney by Oliver Stone and starring Al Pacino, the film concerned Cuban immigrant Tony Montana's rise to power in the BRIAN DE PALMA (b. September 11, 1940 in Newark, United States through the drug trade. The film, while New Jersey) initially planned to follow in his father’s being a critical failure, was a major success commercially. footsteps and study medicine. While working on his Tonight’s film is arguably the apex of De Palma’s career, studies he also made several short films. At first, his films both a critical and commercial success, and earning Sean comprised of such black-and-white films as Bridge That Connery an Oscar win for Best Supporting Actor (the only Gap (1965). He then discovered a young actor whose one of his long career), as well as nominations to fame would influence Hollywood forever. -

Cannibalism in Contact Narratives and the Evolution of the Wendigo Michelle Lietz

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations Graduate Capstone Projects 3-1-2016 Cannibalism in contact narratives and the evolution of the wendigo Michelle Lietz Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lietz, Michelle, "Cannibalism in contact narratives and the evolution of the wendigo" (2016). Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. 671. http://commons.emich.edu/theses/671 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Graduate Capstone Projects at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cannibalism in Contact Narratives and the Evolution of the Wendigo by Michelle Lietz Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Language and Literature Eastern Michigan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Literature Thesis Committee: Abby Coykendall, Ph.D., First Reader Lori Burlingame, Ph.D., Second Reader March 1, 2016 Ypsilanti, Michigan ii Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my kind and caring sisters, and my grounding father. For my mother: thank you for beginning my love of words and for every time reading “one more chapter.” And for every person who has reminded me to guard my spirit during long winters. iii Acknowledgments I am deeply indebted to Dr. Lori Burlingame, for reading all of my papers over and over again, for always letting me take up her office hours with long talks about Alexie, Erdrich, Harjo, Silko and Ortiz, and supporting everything I’ve done with unwavering confidence. -

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES and INDIAN PAINTBRUSH Present An

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES and INDIAN PAINTBRUSH Present An AMERICAN EMPIRICAL PICTURE by WES ANDERSON BRYAN CRANSTON SCARLETT JOHANSSON KOYU RANKIN HARVEY KEITEL EDWARD NORTON F. MURRAY ABRAHAM BOB BALABAN YOKO ONO BILL MURRAY TILDA SWINTON JEFF GOLDBLUM KEN WATANABE KUNICHI NOMURA MARI NATSUKI AKIRA TAKAYAMA FISHER STEVENS GRETA GERWIG NIJIRO MURAKAMI FRANCES MCDORMAND LIEV SCHREIBER AKIRA ITO COURTNEY B. VANCE DIRECTED BY ....................................................................... WES ANDERSON STORY BY .............................................................................. WES ANDERSON ................................................................................................. ROMAN COPPOLA ................................................................................................. JASON SCHWARTZMAN ................................................................................................. and KUNICHI NOMURA SCREENPLAY BY ................................................................. WES ANDERSON PRODUCED BY ...................................................................... WES ANDERSON ................................................................................................. SCOTT RUDIN ................................................................................................. STEVEN RALES ................................................................................................. and JEREMY DAWSON CO-PRODUCER .................................................................... -

Smart Cinema As Trans-Generic Mode: a Study of Industrial Transgression and Assimilation 1990-2005

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DCU Online Research Access Service Smart cinema as trans-generic mode: a study of industrial transgression and assimilation 1990-2005 Laura Canning B.A., M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of Ph.D in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. November 2013 School of Communications Supervisor: Dr. Pat Brereton 1 I hereby certify that that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed:_________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: 58118276 Date: ________________ 2 Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction p.6 Chapter Two: Literature Review p.27 Chapter Three: The industrial history of Smart cinema p.53 Chapter Four: Smart cinema, the auteur as commodity, and cult film p.82 Chapter Five: The Smart film, prestige, and ‘indie’ culture p.105 Chapter Six: Smart cinema and industrial categorisations p.137 Chapter Seven: ‘Double Coding’ and the Smart canon p.159 Chapter Eight: Smart inside and outside the system – two case studies p.210 Chapter Nine: Conclusions p.236 References and Bibliography p.259 3 Abstract Following from Sconce’s “Irony, nihilism, and the new American ‘smart’ film”, describing an American school of filmmaking that “survives (and at times thrives) at the symbolic and material intersection of ‘Hollywood’, the ‘indie’ scene and the vestiges of what cinephiles used to call ‘art films’” (Sconce, 2002, 351), I seek to link industrial and textual studies in order to explore Smart cinema as a transgeneric mode. -

All About Mentoring Issue 54 Autumn 2020

ALL ABOUT MENTORINGA PUBLICATION OF SUNY EMPIRE STATE COLLEGE Issue 54 • Autumn 2020 ALL ABOUT MENTORING Issue 54 • Autumn 2020 ALL ABOUT MENTORING ISSUE 54 AUTUMN 2020 Alan Mandell College Professor of Adult Learning and Mentoring Editor Karen LaBarge Senior Staff Assistant for Faculty Development Associate Editor PHOTOGRAPHY The quotes sprinkled throughout this issue of All Photos courtesy of Stock Studios, About Mentoring offer us a glimpse of the ideas and and faculty and staff of SUNY Empire State College, perspectives of Arthur Chickering, founding academic unless otherwise noted. vice president of SUNY Empire State College, whose contributions over decades and decades have left COVER ARTWORK such an indelible mark on so many individuals and By Donna Gaines Triune (Art on Neptune), 2015 institutions interested in students’ learning and their 32” H x 22.5” W, development. (Please see more information about Acrylic/spray paint/ dirt/found plywood Chickering’s work and impact on page 123.) Photo credit: James Graham PRODUCTION Kirk Starczewski Director of Publications Janet Jones Office Assistant 2 (Keyboarding) College Print Shop Send comments, articles or news to: All About Mentoring c/o Alan Mandell SUNY Empire State College 325 Hudson St., 5th Floor New York, NY 10013-1005 646-230-1255 [email protected] Special thanks: Thanks, as always, to our whole SUNY Empire State College community for voices and ideas that make this publication, and so much else, possible. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorial — Our World ................................................................ 2 Art and Activism at SUNY Empire State College ....................80 Alan Mandell, Manhattan and Saratoga Springs Menoukha Robin Case, Mentor Emerita, Saratoga Springs Connecting Community Scholarship and Service .................. -

TEXTUAL CONVERSATIONS: MODULE a ESSAY: How Has the Context of Each Text Influenced Your Understanding of the Intentional Connections Between Them?

TEXTUAL CONVERSATIONS: MODULE A ESSAY: How has the context of each text influenced your understanding of the intentional connections between them? Textual conversations enable a re-imagination of universal ideas, prompting responders to gain a deeper understanding of the enduring desire for power inherent to the human condition. William Shakespeare’s 1611 comedy, The Tempest, endures through its Jacobean representation of how patriarchal hierarchies within the play are maintained through oppression and restored through the power of illusion. These enduring features are reimagined through displaying Margaret Atwood’s post-modern novel, Hag-seed (2016), where she simultaneously displays paralleling power structures, but instead examines the prevalence of gender roles and modern technology to evoke forgiveness in her Fourth- Wave feminist context. Thus, Atwood’s secular re-imagination resonates through the universal idea of forgiveness, with the dissonant values surrounding each text prompting new post-colonial and feminist interpretations to emerge. Through textual conversations established by Hag-seed, Shakespeare’s representation of the complex power relations between colonizer and colonized prompts contemporary responders to question the morality associated with such subjugation, contextually alluding to the expansionist agendas that characterized the Jacobean Era. Drawing upon the archetypal master-slave dynamic, Shakespeare establishes a microcosmic representation of the colonizer and colonized through “Malignant” Ariel’s repeated reference -

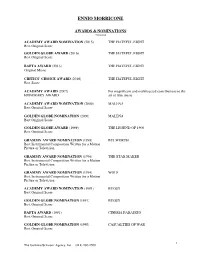

Ennio Morricone

ENNIO MORRICONE AWARDS & NOMINATIONS *selected ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2015) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Original Music CRITICS’ CHOICE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Score ACADEMY AWARD (2007) For magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the HONORARY AWARD art of film music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best O riginal Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1999) THE LEGEND OF 1900 Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1998) BULWORTH Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1996) THE STAR MAKER Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1994) WOLF Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1991) CINEMA PARADISO Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1990) CASUALTIES OF WAR Best Original Score 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 ENNIO MORRICONE ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1987) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1987) THE MISSION Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1980) DAYS OF HEAVEN Anthony Asquith Award fo r Film Music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1979) DAYS OF HEAVEN Best Original Score MOTION PICTURES THE HATEFUL EIGHT Richard N. -

An Introduction to Vladimir Arsen'ev's Life

INTRODUCTION An Introduction to Vladimir Arsen’ev’s Life Work, Colleagues, and Family AMIR KHISAMUTDINOV Abstract: The article is devoted to the famous explorer and writer Vladimir Klavdievich Arsen’ev (1872–1930). He arrived in the Rus- sian Far East in 1900, where he conducted numerous research ex- peditions and engaged in a comprehensive study of the Far East. Arsen’ev studied the lives of the region’s indigenous peoples and published several books, Dersu Uzala being the most famous one. This article is based on Arsen’ev’s personal archives, which are stored in Vladivostok. The article chronicles his life in the Soviet period. It also discusses the punishment of his wives and children. Keywords: Dersu Uzala, ethnography, indigenous people, purges, Soviet era, Vladimir K. Arsen’ev Beginnings Vladimir Klavdievich Arsen’ev, the most famous Russian explorer of the Far East, said on the eve of his death, “I look to the past and see that for myself I did follow a lucky star.”1 Through the Bolshevik Revolution and through the purges, his fate and that of his relatives were typical for that period. Arsen’ev was born in St. Petersburg on August 29, 1872. A little- known fact is that “Arsen’ev” was not his real last name; rather it was Goppmeier, a Dutch name. Arsen’ev’s grandfather was Fedor (Teodor) Ivanovich Goppmeier, who died in 1866. He was the manager of an estate, who had a son, Klavdii Fedorovich, born on March 11, 1848. Gopp meier did not succeed in having Klavdii legalized, so he was given the surname of a man called Arsenii, who was present at his christen- ing, hence the name “Arsen’ev.” In retrospect, this was a fortunate turn Sibirica Vol.