Some Notes on John Zorn's Cobra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acclaimed Drummer-Composer John

Bio information: THE CLAUDIA QUINTET Title: SUPER PETITE (Cuneiform Rune 427) Format: CD / DIGITAL RELEASE DATE: JUNE 24, 2016 Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American & world radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / POST-JAZZ Acclaimed Drummer-Composer John Hollenbeck Pens Rich, Complex Tunes for an Era of Short Attention Spans on The Claudia Quintet's 8th album – Super Petite – a Potent Package that Condenses Virtuoso Playing and a Wealth of Ideas into Ten Compact Songs Short doesn’t necessarily mean simple. Drummer-composer John Hollenbeck acrobatically explores the dichotomy between brevity and complexity on Super Petite, the eighth release by the critically acclaimed, proudly eccentric Claudia Quintet. The oxymoronic title of the band’s newest album on Cuneiform Records captures the essence of its ten new compositions, which pack all of the wit and virtuosity that listeners have come to expect from the Claudia Quintet into the time frame of radio-friendly pop songs. As always, Hollenbeck’s uncategorizable music – which bridges the worlds of modern jazz and new music in surprising and inventive ways - is realized by Claudia’s longstanding line-up: clarinetist/tenor saxophonist Chris Speed, vibraphonist Matt Moran, bassist Drew Gress, and accordionist Red Wierenga. Over the course of 19 years and 8 albums, the band has forged an astounding chemistry and become expert at juggling mind-boggling dexterity with inviting emotion and spirit. Like the band’s name, the title Super Petite originated as an affectionate nickname for one of the band’s fans. -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

Jazz-Fest-2017-Program-Guide.Pdf

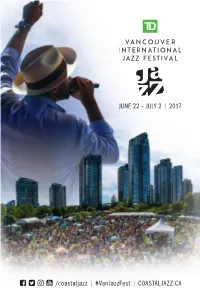

JUNE 22 – JULY 2 | 2017 /coastaljazz | #VanJazzFest | COASTALJAZZ.CA 20TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017 181 CHAN CENTRE PRESENTS SERIES The Blind Boys of Alabama with Ben Heppner I SEP 23 The Gloaming I OCT 15 Zakir Hussain and Dave Holland: Crosscurrents I OCT 28 Ruthie Foster, Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Carrie Rodriguez I NOV 8 The Jazz Epistles: Abdullah Ibrahim and Hugh Masekela I FEB 18 Lila Downs I MAR 10 Daymé Arocena and Roberto Fonseca I APR 15 Circa: Opus I APR 28 BEYOND WORDS SERIES Kate Evans: Threads I SEP 29 Tanya Tagaq and Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory I MAR 16+17 SUBSCRIPTIONS ON SALE MAY 2 DAYMÉ AROCENA THE BLIND BOYS OF ALABAMA HUGH MASEKELA TANYA TAGAQ chancentre.com Welcome to the 32nd Annual TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival TD is pleased to bring you the 2017 TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival, a widely loved and cherished world-class event celebrating talented and culturally diverse artists from Canada and around the world. In Vancouver, we share a love of music — it is a passion that brings us together and enriches our lives. Music is powerful. It can transport us to faraway places or trigger a pleasant memory. Music is also one of many ways that TD connects with customers and communities across the country. And what better way to come together than to celebrate music at several major music festivals from Victoria to Halifax. ousands of fans across British Columbia — including me — look forward to this event every year. I’m excited to take in the music by local and international talent and enjoy the great celebration this festival has to o er. -

Blabla Bio Fred Frith

BlaBla Bio Fred Frith Multi-instrumentalist, composer, and improviser Fred Frith has been making noise of one kind or ano- ther for almost 50 years, starting with the iconic rock collective Henry Cow, which he co-founded with Tim Hodgkinson in 1968. Fred is best known as a pioneering electric guitarist and improviser, song-writer, and composer for film, dance and theater. Through bands like Art Bears, Massacre, Skeleton Crew, Keep the Dog, the Fred Frith Guitar Quartet and Cosa Brava, he has stayed close to his roots in rock and folk music while branching out in many other directions. His compositions have been performed by ensembles ranging from Arditti Quartet and the Ensemble Modern to Concerto Köln and Galax Quartet, from the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra to ROVA and Arte Sax Quartets, from rock bands Sleepytime Gorilla Museum and Ground Zero to the Glasgow Improvisers’ Orchestra. Film music credits include the acclaimed documentaries Rivers and Tides, Touch the Sound and Leaning into the Wind, directed by Thomas Riedelsheimer, The Tango Lesson, Yes and The Party by Sally Potter, Werner Penzel’s Zen for Nothing, Peter Mettler’s Gods, Gambling and LSD, and the award-winning (and Oscar-nominated) Last Day of Freedom, by Nomi Talisman and Dee Hibbert- Jones. Composing for dance throughout his long career, Fred has worked with Rosalind Newman and Bebe Miller in New York, François Verret and Catherine Diverrès in France, and Amanda Miller and the Pretty Ugly Dance Company over the course of many years in Germany, as well as composing for two documentary films on the work of Anna Halprin. -

Printcatalog Realdeal 3 DO

DISCAHOLIC auction #3 2021 OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! This is the 3rd list of Discaholic Auctions. Free Jazz, improvised music, jazz, experimental music, sound poetry and much more. CREATIVE MUSIC the way we need it. The way we want it! Thank you all for making the previous auctions great! The network of discaholics, collectors and related is getting extended and we are happy about that and hoping for it to be spreading even more. Let´s share, let´s make the connections, let´s collect, let´s trim our (vinyl)gardens! This specific auction is named: OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! Rare vinyls and more. Carefully chosen vinyls, put together by Discaholic and Ayler- completist Mats Gustafsson in collaboration with fellow Discaholic and Sun Ra- completist Björn Thorstensson. After over 33 years of trading rare records with each other, we will be offering some of the rarest and most unusual records available. For this auction we have invited electronic and conceptual-music-wizard – and Ornette Coleman-completist – Christof Kurzmann to contribute with some great objects! Our auction-lists are inspired by the great auctioneer and jazz enthusiast Roberto Castelli and his amazing auction catalogues “Jazz and Improvised Music Auction List” from waaaaay back! And most definitely inspired by our discaholic friends Johan at Tiliqua-records and Brad at Vinylvault. The Discaholic network is expanding – outer space is no limit. http://www.tiliqua-records.com/ https://vinylvault.online/ We have also invited some musicians, presenters and collectors to contribute with some records and printed materials. Among others we have Joe Mcphee who has contributed with unique posters and records directly from his archive. -

WXU Und Hat Hut – Stets Auf Der Suche Nach Neuem Werner X

r 2017 te /1 in 8 W ANALOGUE AUDIO SWITZERLAND ASSOCIATION Verein zur Erhaltung und Förderung der analogen Musikwiedergabe Das Avantgarde-Label «Hat Hut» Wenig bekannte Violinvirtuosen und Klavierkonzerte Schöne klassische und moderne Tonarme e ill R Aus der WXU und Hat Hut – stets auf der Suche nach Neuem Werner X. Uehlinger, Modern Jazz und Contemporary Music Von Urs Mühlemann Seit 42 Jahren schon gibt es das Basler Plattenlabel «Hat Hut». In dieser Zeit hat sich die Musikindust- rie grundlegend verändert. Label-Gründer Werner X. Uehlinger, Jahrgang 1935, Träger des Kulturprei- ses 1999 der Stadt Basel, hält allen Stürmen stand – und veröffentlicht mit sicherem Gespür immer wieder aussergewöhnliche Aufnahmen. «Seit 1975, ein Ohr in die Zukunft»: Dieses Motto steht als Signatur in allen E-Mails von Werner X. Uehlinger (auch als ‚WXU‘ bekannt). Den Gründer des unabhängigen Schweizer Labels «Hat Hut», das u.a. 1990 von der progressiven New Yorker Zeitschrift «Village Voice» unter die fünf weltbesten Labels gewählt wurde und internationale Wertschätzung nicht nur in Avantgarde-Kreisen geniesst, lernte ich vor mehr als 40 Jahren persönlich kennen. Wir verloren uns aus den Augen, aber ich stiess im Laufe meiner musikalischen Entwicklung immer wieder auf ‚WXU‘ und seine exquisiten Produkte. Nun hat er – als quasi Ein-Mann-Betrieb – sein Lebenswerk in die Hände von «Outhere» gelegt; das Unterneh- men vereint verschiedene Labels für klassische und für zeitgenössische Musik unter einem Dach. Das war für mich eine Gelegenheit, wieder Kontakt aufzunehmen. Wir trafen uns im Februar und im Mai 2017 zu längeren Gesprächen und tauschten uns auch schriftlich und telefonisch aus. -

Some Notes on John Zorn's Cobra

Some Notes on John Zorn’s Cobra Author(s): JOHN BRACKETT Source: American Music, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Spring 2010), pp. 44-75 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/americanmusic.28.1.0044 . Accessed: 10/12/2013 15:16 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Music. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 198.40.30.166 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 15:16:53 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JOHN BRACKETT Some Notes on John Zorn’s Cobra The year 2009 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of John Zorn’s cele- brated game piece for improvisers, Cobra. Without a doubt, Cobra is Zorn’s most popular and well-known composition and one that has enjoyed remarkable success and innumerable performances all over the world since its premiere in late 1984 at the New York City club, Roulette. Some noteworthy performances of Cobra include those played by a group of jazz journalists and critics, an all-women performance, and a hip-hop ver- sion as well!1 At the same time, Cobra is routinely played by students in colleges and universities all over the world, ensuring that the work will continue to grow and evolve in the years to come. -

Conference Faculty Jason Adler

Conference Faculty Jason Adler...................................................................................................................................... 1 Mark A. Cohen................................................................................................................................ 2 Hon. Linda Kuczma ........................................................................................................................ 3 Hon. Pauline Newman .................................................................................................................... 4 Carlos Aboim .................................................................................................................................. 5 Kenneth R. Adamo.......................................................................................................................... 6 Themi Anagnos ............................................................................................................................... 7 Ian Ballon ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Patrick G. Burns .............................................................................................................................. 9 Christopher V. Carani ................................................................................................................... 10 Charisse Castagnoli ...................................................................................................................... -

TT-2019-Versie 11

PROGRAM PROGRAM SUBJECT TO CHANGE FRIDAY JULY 12 FOR LATEST CHANGES, CHECK: WWW.NORTHSEAJAZZ.COM 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 19:00 19:30 20:00 20:30 21:00 21:30 22:00 22:30 23:00 23:30 00:00 00:30 AHOY OPEN: 14:30 BURT AMAZON DIANA KRALL BACHARACH GILBERTO GIL GARY BARTZ CHUCHO VALDES STEVE GADD BAND ANOTHER EARTH ORQUESTA AKOKÁN HUDSON featuring RAVI COLTRANE JAZZ BATÁ & CHARLES TOLLIVER CURTIS NILE HARDING RAG’N’BONEMAN JOE JACKSON TOWER OF POWER JOSÉ JAMES LEAN ON ME BLOOD ORANGE ANITA BAKER JACOB BANKS MAAS with NOORDPOOL ORKEST MAKAYA McCRAVEN ARTIST IN RESIDENCE BRAXTON COOK UNIVERSAL BEINGS ROBERT GLASPER THE INTERNET CONGO with BRANDEE YOUNGER with CHRIS DAVE, DERRICK HODGE and JOEL ROSS and special guest YASIIN BEY CONGO SON SWAGGA SON SWAGGA THEON CROSS THEON CROSS SQUARE VERSIE 11 - 26 JUNI 2019 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 19:00 19:30 20:00 20:30 21:00 21:30 22:00 22:30 23:00 23:30 00:00 00:30 JOHN ZORN PRESENTS BAGATELLES MARATHON featuring MASADA, SYLVIE COURVOISIER and MARK FELDMAN, MARY HALVORSON QUARTET, CRAIG TABORN, NIK BÄRTSCH’S DARLING TRIGGER, ERIK FRIEDLANDER and MIKE NICOLAS, JOHN MEDESKI TRIO, NOVA QUARTET, GYAN RILEY and JULIAN LAGE, RONIN BRIAN MARSELLA TRIO, IKUE MORI, KRIS DAVIS, PETER EVANS, ASMODEUS DAFNIS PRIETO RYMDEN CHRISTIAN SANDS BUGGE WESSELTOFT BEN WENDEL BOB REYNOLDS MADEIRA BIG BAND TRIO DAN BERGLUND, SEASONS BAND GROUP feat. -

East Side, Far Side—All Around the Sound

EAST SIDE, FAR SIDE—ALL AROUND THE SOUND a/k/a IT’S NOT WHERE YOU’RE FRUM, IT’S WHERE YOU’RE AT By GARY LUCAS I’m looking over yonder’s wall into the valley of eventual conscription into the Polish army, of the shadow of the (partially) fallen Eden which was mandatory at the time for all male known as the Lower East Side from the vantage citizens. He arrived at Ellis Island with his mother point of 30 years residence in the West Village. on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, circa 1897, You’re probably wondering why I’m here…as in, speaking only Yiddish and Polish. She intended what the heck is an to move immediately unreconstructed denizen upstate to Syracuse, of the far West Village where family awaited doing in a book devoted them. to the Lower East Side? But due to the ban Well, as an avant- against travel on the garde musician who has High Holy Days, they toiled for years in the were detained a couple of vineyards of myriad days on the LES. The transient clubs/watering local Hebrew Aid holes du jour/toilettes Society gave them situated on the Lower temporary shelter on the East Side, I gotta right to Bowery, an experience offer my two cents plain Gods and Monsters debut at the old Knitting Factory my grandfather was on what is basically a on Houston Street in July 1989, l to r: Paul Now, Gary never to forget. It was a Lucas, Tony Thunder Smith, and Jared Nickerson very boring cultural turf primal memory war conducted on the rapidly shifting grounds we emblazoned in his consciousness, wherein he first New Yorkers walk on—grounds once abounding tasted the hitherto unknown sybaritic pleasures of with the jouissance of spontaneous space for all, life in these United States, as opposed to the present-day manicured On his first night at the temporary, the playgrounds reserved as the exclusive purview of Hebrew Aid Society folks running the shelter millionaire bohemia…grounds currently being made a gift of bananas to everyone there. -

Press Kit 2017

BIOGRAPHY BIOGRAPHY One of his generation’s extraordinary talents, Scott Tixier has made a name for himself as a violinist-composer of wide- ranging ambition, individuality and drive — “the future of jazz violin” in the words of Downbeat Magazine and “A remarkable improviser and a cunning jazz composer” in those of NPR. The New York City-based Tixier, born in 1986 in Montreuil, France has performed with some of the leading lights in jazz and music legends from Stevie Wonder to NEA jazz master Kenny Barron; as a leader as well. Tixier’s acclaimed Sunnyside album “Cosmic Adventure” saw the violinist performing with a all star band “taking the jazz world by storm” as the All About Jazz Journal put it. The Village Voice called the album “Poignant and Reflective” while The New York Times declared “Mr. Tixier is a violinist whose sonic palette, like his range of interests, runs open and wide; on his new album, “Cosmic Adventure,” he traces a line through chamber music, Afro-Cuban groove and modern jazz.” When JazzTimes said"Tixier has a remarkably vocal tone, and he employs it with considerable suspense. Cosmic Adventure is a fresh, thoroughly enjoyable recording!" Tixier studied classical violin at the conservatory in Paris. Following that, he studied improvisation as a self-educated jazz musician. He has been living in New York for over a decade where he performed and recorded with a wide range of artists, including, Stevie Wonder, Kenny Barron, John Legend, Ed Sheeran, Charnett Moffett, Cassandra Wilson, Chris Potter, Christina Aguilera, Common, Anthony Braxton, Joss Stone, Gladys Knight, Natalie Cole, Ariana Grande, Wayne Brady, Gerald Cleaver,Tigran Hamasyan and many more He played in all the major venues across the United States at Carnegie Hall, the Radio City Music Hall, Madison Square Garden, Barclays Center, Jazz at Lincoln Center, the Blue Note Jazz Club, the Apollo Theater, the Smalls Jazz Club, The Stone, Roulette, Joe's Pub, Prudential Center and the United States Capitol. -

Gerry Hemingway Quartet Press Kit (W/Herb Robertson and Mark

Gerry Hemingway Quartet Herb Robertson - trumpet Ellery Eskelin - tenor saxophone Mark Dresser- bass Gerry Hemingway – drums "Like the tightest of early jazz bands, this crew is tight enough to hang way loose. *****" John Corbett, Downbeat Magazine Gerry Hemingway, who developed and maintained a highly acclaimed quintet for over ten years, has for the past six years been concentrating his experienced bandleading talent on a quartet formation. The quartet, formed in 1997 has now toured regularly in Europe and America including a tour in the spring of 1998 with over forty performances across the entire country. “What I experienced night after night while touring the US was that there was a very diverse audience interested in uncompromising jazz, from young teenagers with hard core leanings who were drawn to the musics energy and edge, to an older generation who could relate to the rhythmic power, clearly shaped melodies and the spirit of musical creation central to jazz’s tradition that informs the majority of what we perform.” “The percussionist’s expressionism keeps an astute perspective on dimension. He can make you think that hyperactivity is accomplished with a hush. His foursome recently did what only a handful of indie jazzers do: barnstormed the U.S., drumming up business for emotional abstraction and elaborate interplay . That’s something ElIery Eskelin, Mark Dresser and Ray Anderson know all about.“ Jim Macnie Village Voice 10/98 "The Quartet played the compositions, stuffed with polyrhythms and counterpoints, with a swinging