Evolution of Medicinal Plant Knowledge in Southern Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

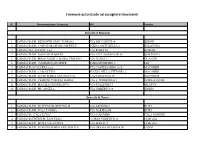

Farmacie Autorizzate Ad Accogliere Tirocinanti

Farmacie autorizzate ad accogliere tirocinanti N° Denominazione Farmacia VIA Località Distretto di Macomer 1 FARMACIA DR. DEMONTIS GIOV. TOMASO VIA DEI CADUTI 14 BIRORI 2 FARMACIA DR. CAPPAI GRAZIANO MICHELE P.ZZA CORTE BELLA 3 BOLOTANA 3 FARMACIA CADEDDU s.a.s. VIA ROMA 56 BORORE 4 FARMACIA DR. BIANCHI ALBERTO VIA VITT. EMANUELE 56 BORTIGALI 5 FARMACIA DR. PIRAS ANGELA MARIA CRISTINA VIA DANTE 1 DUALCHI 6 FARMACIA DR. GAMMINO GIUSEPPE P.ZZA MUNICIPIO 3 LEI 7 FARMACIA SCALARBA s.a.s. VIA CASTELSARDO 12/A MACOMER 8 FARMACIA DR. CABOI LUIGI PIAZZA DELLA VITTORIA 2 MACOMER 9 FARMACIA DR. SECHI MARIA ANTONIETTA VIA SARDEGNA 59 MACOMER 10 FARMACIA DR. CHERCHI TOMASO MARIA VIA E. D'ARBOREA 1 NORAGUGUME 11 FARMACIA DR. MASALA GIANFRANCO VIA STAZIONE 13 SILANUS 12 FARMACIA DR. PIU ANGELA VIA UMBERTO 88 SINDIA Distretto di Nuoro 1 FARMACIA DR. BUFFONI GIUSEPPINA M. VIA ASPRONI 9 BITTI 2 FARMACIA DR. TOLA TONINA VIA GARIBALDI BITTI 3 FARMACIA "CALA LUNA" VIA COLOMBO CALA GONONE 4 FARMACIA EREDI DR. FANCELLO CORSO UMBERTO 13 DORGALI 5 FARMACIA DR. MURA VALENTINA VIA MANNU 1 DORGALI 6 FARMACIA DR. BUFFONI MARIA ANTONIETTA VIA GRAZIA DELEDDA 80 FONNI 7 FARMACIA DR. MEREU CATERINA VIA ROMA 230 GAVOI 8 FARMACIA DR. SEDDA GIANFRANCA LARGO DANTE ALIGHIERI 1 LODINE 9 FARMACIA DR. PIRAS PIETRO VIA G.M.ANGIOJ LULA 10 FARMACIA DR. FARINA FRANCESCO SAVERIO VIA VITT. EMANUELE MAMOIADA 11 FARMACIA SAN FRANCESCO di Luciana Canargiu VIA SENATORE MONNI 2 NUORO 12 FARMACIA DADDI SNC di FRANCESCO DADDI e C. PIAZZA VENETO 3 NUORO 13 FARMACIA DR. -

Allevamento Del Suino, Produzione E Conservazione Dei Salumi

Dipartimento per le produzioni zootecniche Servizio produzioni zootecniche Corso teorico-pratico Allevamento del suino, produzione e conservazione dei salumi Attività di formazione rivolta ai gestori di agriturismi, fattorie didattiche e allevatori della Gallura Programma delle lezioni e calendario degli incontri Sportello Unico Territoriale dell’Alta Ogliastra Via N. Bixio n. 2, Tortolì - Tel. 0782 623084, fax 0782 628033 Data SUT Sede corso Argomento 13-ott-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Presentazione Corso Situazione regionale della filiera suinicola Tipologia e sistemi di allevamento dei suini 18-ott-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Le razze Gestione dell'allevamento Organizzazione delle varie fasi 20-ott-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Gestione sanitaria: Principali malattie Biosicurezza in allevamento 25-ott-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Alimentazione: Gli alimenti e le sostanze nutritive Principi di razionamento 27-ott-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Lezione pratica Foresta Burgos. Il suino di razza sarda: storia, attualità e prospettive; visita allevamento all'aperto dell'AGRIS. Eventuale visita guidata ad altro/i allevamento/i. 3-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Macellazione, qualità delle carni e tagli 8-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Classificazione dei salumi. Materie prime per la produzione dei salumi: caratteristiche fisiche, chimiche e microbiologiche; Additivi, aromi e starter 10-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Lezione pratica sulla trasformazione e lavorazione dei salumi 15-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana La macellazione familiare e in agriturismo, La trasformazione artigianale: Iter autorizzativo e caratteristiche dei locali Procedure autorizzative per l'esportazione delle carni suine al di fuori della regione 17-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana La multifunzionalità dell'azienda agricola 22-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Valutazione dei salumi: Analisi sensoriale Principali difetti Sportello Unico Territoriale della Barbagia Via De Gasperi, Gavoi - Tel. -

AZIENDA SANITARIA LOCALE N Olbia

SERVIIZIIO SANIITARIIO REGIIONE AUTONOMA DELLA SARDEGNA AZIENDA SANITARIA LOCALE N°2 Olbia GRADUATORIA “ALLEGATO B” ALLA DELIBERAZIONE DEL DIRETTORE GENERALE N°1553 DEL 21.06.2011 N° COGNOME NOME LUOGO DI NASCITA DATA DI NASCITA PUNTEGGIO NOTE 1 SOTGIU ANDREA SASSARI 08/06/1951 8,910 2 LEON SUAREZ ANA VERONICA LAS PALMAS DE GRAN CANARIA 25/11/1970 5,360 3 GIORDANO ORSINI EUGENIO TORRE DEL GRECO 22/12/1982 4,172 4 TOSI ELIANE CURITIBA 20/07/1966 2,906 5 DI PASQUALE LUCA ISERNIA 13/05/1983 2,589 6 BIOSA ANTONIO LA MADDALENA 17/01/1964 2,520 7 BARONE RAFFAELE GELA 29/03/1986 2,460 8 PITZALIS VALERIA CAGLIARI 22/06/1978 2,369 9 GAETANI MARIANNA FOGGIA 13/04/1983 2,320 10 ISU ALESSANDRO SAN GAVINO MONREALE 05/02/1974 2,270 11 SERAFINI VINCENZO ASCOLI PICENO 19/03/1977 2,240 12 TALANA MICHELE IGLESIAS 21/06/1987 1,780 p. per età 13 MELIS MIRKO CAGLIARI 06/11/1986 1,780 14 ABBRUSCATO RICCARDO AGRIGENTO 14/12/1981 1,660 15 PODDA SILVIA ARBUS 10/07/1985 1,642 1 Pubblica selezione - Collaboratore Professionale Sanitario-Tecnico Sanitario di Radiologia Medica – cat. D. 16 LODATO NICOLA CAVA DE' TIRRENI 15/05/1982 1,570 p. per età 17 DE DOMINICIS GIANLUCA ARIANO IRPINO 14/02/1977 1,570 18 DI CAIRANO LUCA PASCAL LUGANO 15/08/1981 1,550 19 LIOCE SABRINA SAN SEVERO 06/10/1987 1,460 20 D'AMICO ALFONSO CAVA DE' TIRRENI 14/03/1981 0,990 21 CALABRO' FRANCESCA CAGLIARI 14/03/1985 0,961 22 CARBONE CARMINE AVELLINO 17/11/1975 0,947 23 RUNZA GIUSEPPE ROSOLINI 03/03/1977 0,920 24 MICILLO ALESSANDRO LATINA 02/04/1986 0,902 25 PLACENINO MIRELLA SAN GIOVANNI ROTONDO 12/04/1987 0,800 26 BIBBO' ANDREA BENEVENTO 15/09/1987 0,710 p. -

VOYAGE to VALLETTA from the ‘Eternal City’ to the ‘Silent City’ Aboard the Variety Voyager 16Th to 24Th May 2016

LAUNCH OFFER - SAVE £300 PER PERSON VOYAGE TO VALLETTA From the ‘Eternal City’ to the ‘Silent City’ aboard the Variety Voyager 16th to 24th May 2016 All special offers are subject to availability. Our current booking conditions apply to all reservations and are available on request. Cover image: View over the Greek Doric Temple, Segesta, Sicily NOBLE CALEDONIA ere is a rare opportunity to visit both Ruins of the Greek temple at Selinunte Sardinia and Sicily, the Mediterranean’s Htwo largest islands combined with time to explore some of Malta’s wonders from the comfort of the private yacht, the Variety Voyager. This is not an itinerary which a large cruise ship could operate but one which is ideal for our 72-passenger vessel. All three islands feature a magnificent array of ancient ruins and attractive towns and villages which we will visit during our guided excursions whilst we have also allowed for ample time to explore independently. With comfortable temperatures and relatively crowd free sites, May is the perfect time to discover these islands and in addition we have the added benefit of excellent local THE ITINERARY Day 1 London to Rome, Italy. ITALY guides along the way and a knowledgeable Fly by scheduled flight. Arrive Q this afternoon and transfer to the onboard guest speaker who will bring to life Isla Maddalena Rome Olbia• • Variety Voyager in Civitavecchia. • •Civitavecchia Enjoy a welcome drink and dinner all we see. SARDINIA as we sail this evening to Sardinia. TYRRHENIAN SEA Cagliari• Day 2 Isla Maddalena & Olbia, Piazza • Armerina Sardinia. In 1789 Napoleon, then Mazara del • Vallo SICILY a young artillery commander was •Gela thwarted in his attempt to take GOZOQ • •Valletta the Maddalena archipelago by MALTA local Sardinian forces and in 1803 Lord Nelson arrived. -

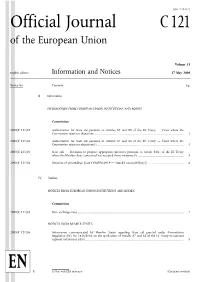

Official Journal C121

ISSN 1725-2423 Official Journal C 121 of the European Union Volume 51 English edition Information and Notices 17 May 2008 Notice No Contents Page II Information INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS AND BODIES Commission 2008/C 121/01 Authorisation for State aid pursuant to Articles 87 and 88 of the EC Treaty — Cases where the Commission raises no objections ............................................................................................. 1 2008/C 121/02 Authorisation for State aid pursuant to Articles 87 and 88 of the EC Treaty — Cases where the Commission raises no objections (1) .......................................................................................... 4 2008/C 121/03 State aids — Decisions to propose appropriate measures pursuant to Article 88(1) of the EC Treaty where the Member State concerned has accepted those measures (1) ................................................ 5 2008/C 121/04 Initiation of proceedings (Case COMP/M.4919 — Statoil/Conocophillips) (1) ..................................... 6 IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS AND BODIES Commission 2008/C 121/05 Euro exchange rates ............................................................................................................... 7 NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES 2008/C 121/06 Information communicated by Member States regarding State aid granted under Commission Regulation (EC) No 1628/2006 on the application of Articles 87 and 88 of the EC Treaty to national regional investment aid (1) ...................................................................................................... -

A Palaeoenvironmental Reconstruction of the Middle Jurassic of Sardinia (Italy) Based on Integrated Palaeobotanical, Palynological and Lithofacies Data Assessment

Palaeobio Palaeoenv DOI 10.1007/s12549-017-0306-z ORIGINAL PAPER A palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of the Middle Jurassic of Sardinia (Italy) based on integrated palaeobotanical, palynological and lithofacies data assessment Luca Giacomo Costamagna1 & Evelyn Kustatscher2,3 & Giovanni Giuseppe Scanu1 & Myriam Del Rio1 & Paola Pittau1 & Johanna H. A. van Konijnenburg-van Cittert4,5 Received: 15 May 2017 /Accepted: 19 September 2017 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract During the Jurassic, Sardinia was close to con- diverse landscape with a variety of habitats. Collection- tinental Europe. Emerged lands started from a single is- and literature-based palaeobotanical, palynological and land forming in time a progressively sinking archipelago. lithofacies studies were carried out on the Genna Selole This complex palaeogeographic situation gave origin to a Formation for palaeoenvironmental interpretations. They evidence a generally warm and humid climate, affected occasionally by drier periods. Several distinct ecosystems can be discerned in this climate, including alluvial fans This article is a contribution to the special issue BJurassic biodiversity and with braided streams (Laconi-Gadoni lithofacies), paralic ^ terrestrial environments . swamps and coasts (Nurri-Escalaplano lithofacies), and lagoons and shallow marine environments (Ussassai- * Evelyn Kustatscher [email protected] Perdasdefogu lithofacies). The non-marine environments were covered by extensive lowland and a reduced coastal Luca Giacomo Costamagna and tidally influenced environment. Both the river and the [email protected] upland/hinterland environments are of limited impact for Giovanni Giuseppe Scanu the reconstruction. The difference between the composi- [email protected] tion of the palynological and palaeobotanical associations evidence the discrepancies obtained using only one of those Myriam Del Rio [email protected] proxies. -

Graduatoria Definitiva

Unione dei Comuni Valle del Pardu e dei Tacchi OGLIASTRA MERIDIONALE Cardedu-Gairo-Jerzu-Osini-Perdasdefogu-Tertenia-Ulassai-Ussassai Inserimento socio-lavorativo di soggetti professionalizzati – annualità 2018 Ufficio di Piano GRADUATORIA DEFINITIVA n. Nome Data nascita Residenza Titolo studio Tot 1 Loru Enrica S. Gavino 21/05/1988 Jerzu Laurea specialistia Economia e Commercio 28,50 2 Usai Serenella Lanusei 25/08/1982 Ulassai Laurea Specialistica Scienza dell'amministrazione 24,50 3 Pittalis Giada Lanusei 25/11/1988 Gairo Laurea triennale Amministrazione 23,50 4 Chillotti Marta Lanusei 09/12/1992 Jerzu Laurea magistrale Biologia 23,00 Laurea triennale Mediazione Linguistica e 5 Krautsova Antanina Minsk 20/01/1986 Gairo specialistica in Comunicazione internazionale 23,00 6 Congera Luisa Lanusei 07/04/1979 Ulassai Laurea magistrale Giurisprudenza 23,00 7 Locci Michela Lanusei 22/01/1986 Tertenia Laurea specialistica in Architettura 21,50 8 Deidda Francesca Lanusei 02/08/1991 Ulassai Laurea triennale e magistrale in Scienze geologiche 21,00 9 Deidda Laura Lanusei 2/9/1990 Perdas Laurea magistrale ingegneria civile 21,00 10 Piroddi Luisa Cagliari 01/04/1989 Ulassai Laurea triennale Scienze Politiche 21,00 11 Garau Cesare Lanusei 08/10/1984 Jerzu Laurea specialistica Ingegneria civile 19,50 12 Cannas Marilena Lanusei 15/05/1984 Osini Laurea triennale scienze tecniche erboristiche 19,00 13 Demurtas Roberta Lanusei 19/04/1989 Ulassai Laurea triennale Scienze Turismo 17,50 14 Pavoletti Luca Livorno 26/8/1984 Ussassai Laurea triennale Tecnico -

COMUNE DI SINISCOLA PROVINCIA DI NUORO SERVIZIO LAVORI PUBBLICI, MANUTENZIONI ED ESPROPRIAZIONI Via Roma 125 – Tel

COMUNE DI SINISCOLA PROVINCIA DI NUORO SERVIZIO LAVORI PUBBLICI, MANUTENZIONI ED ESPROPRIAZIONI Via Roma 125 – tel. 0784/870829 - Telefax 0784/878300 Info: www.comune.siniscola,.nu.it Prot. N. 11304 del 21.06.2011 OGGETTO: AVVISO DI GARA ESPERITA INTERVENTI DI MANUTENZIONE STRAORDINARIA DELL’IMPIANTO DI ILLUMINAZIONE PUBBLICA PER IL RISPARMIO ENERGETICO E IL CONTENIMENTO DELL’INQUINAMENTO LUMINOSO Determinazione del Responsabile del Servizio LL.PP. n. 187 del 17.06.2011 IMPORTO COMPLESSIVO DEI LAVORI: €. 165.699,39 di cui: Importo dei Lavori a Base d’Asta € 161.199,39 Oneri per la Sicurezza(non soggetti a ribasso) €. 4.500,00 SISTEMA DI AGGIUDICAZIONE: Ai sensi dell'art. 122, comma 9 D.lgs. 163/2006 la gara, con ammissibilità di offerte solo al ribasso, è stata esperita con il criterio del prezzo più basso, inferiore a quello posto a base di gara, determinato mediante ribasso sull'elenco prezzi posto a base d’asta, a norma dell'art. 18, comma 1, lett. a) punto 3 della L.R. N° 5 del 07.08.2007, AGGIUDICAZIONE PROVVISORIA: Aggiudicataria in via provvisoria, fatte salve le ulteriori verifiche e determinazioni dell’amministrazione la Ditta PALANDRI E BELLI SRL con sede in Prato (PO) in VIA LEPANTO N. 23 -59100 PRATO (PO) con il ribasso percentuale del 19,279 %. OFFERTE PERVENUTE: n. 71 OFFERTE AMMESSE: n. 64 1 DITTA PARTECIPANTE Città Indirizzo - N. Fax N.PROT. DEL VIA ZACCAGNUOLO,7184016 FELCO costruzioni PAGANI (SA) FAX prot.n.9493 generali s.r.l PAGANI (SA) 0818237956 DEL30/05/11 TRO.LUX.DI TROGU P.I.PAOLO VIA SANT ANTONIO,12 INSTALLAZIONE DI FAX 0782 803233 ISILI prot.n.9608 IMPIANTI ELETTRICI ISILI (CA) DEL31/05/11 LOC.MURDEGU E SESU MILLENIUM IMPIANTI 09070 MILIS (OR) TEL E prot.n.9609 SRL MILIS (OR) FAX 0783.51339 DEL31/05/11 C/DA CEPIE ENERGY GIARDINELLO ,S.N.90040GIARDINELLO prot. -

Elenco Corse

Centro Interuniversitario Regione Autonoma della Sardegna Provincia dell’Ogliastra Ricerche economiche e mobilità PROVINCIA DELL’OGLIASTRA ELENCO CORSE PROGETTO DEFINITIVO Centro Interuniversitario Regione Autonoma della Sardegna Provincia dell’Ogliastra Ricerche economiche e mobilità UNIVERSITÁ DEGLI STUDI DI CAGLIARI CIREM CENTRO INTERUNIVERSITARIO RICERCHE ECONOMICHE E MOBILITÁ Responsabile Scientifico Prof. Ing. Paolo Fadda Coordinatore Tecnico/Operativo Dott. Ing. Gianfranco Fancello Gruppo di lavoro Ing. Diego Corona Ing. Giovanni Durzu Ing. Paolo Zedda Centro Interuniversitario Regione Autonoma della Sardegna Provincia dell’Ogliastra Ricerche economiche e mobilità SCHEMA DEI CORRIDOI ORARIO CORSE CORSE ‐ OGLIASTRA ‐ ANDATA RITORNO CORRIDOIO "GENNA e CRESIA" CORRIDOIO "GENNA e CRESIA" Partenza Arrivo Nome Linee Nome Corsa Km Origine Destinazione Tipologia Veicolo Partenza Arrivo Nome Linee Nome Corsa Km Origine Destinazione Tipologia Veicolo 06:15 07:25 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C1 ‐ fer 40,151 JERZU ARBATAX BUS_15_POSTI A 17:40 18:50 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C1 ‐ fer 40,151 ARBATAX JERZU BUS_15_POSTI R 06:50 08:00 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C ‐ scol 43,012 OSINI NUOVO TORTOLI' STAZIONE FDS BUS_55_POSTI A 13:40 14:50 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C ‐ scol 43,012 TORTOLI' STAZIONE FDS OSINI NUOVO BUS_55_POSTI R 07:00 07:45 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C2 ‐ scol 28,062 LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 JERZU BUS_55_POSTI A 13:42 14:27 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C2 ‐ scol 28,062 JERZU LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 BUS_55_POSTI R 07:15 08:00 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C1 ‐ scol 28,062 JERZU LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 BUS_55_POSTI A 13:42 14:27 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C1 ‐ scol 28,062 LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 JERZU BUS_55_POSTI R 07:30 07:58 LINEA ROSSA 3 C ‐ scol 18,316 BARI SARDO LANUSEI PIAZZA V. -

N.001-2019 Istituz SUAPE Presso Unione Comuni D'ogliastra

COMUNE DI CARDEDU PROVINCIA DI NUORO DELIBERAZIONE DEL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE n. 1 del 24/01/2019 COPIA Oggetto: Istituzione dello Sportello Unico per le Attività Produttive e per l'Attività Edilizia SUAPE Associato Ogliastra 2, presso lUnione Comuni d'Ogliastra. Approvazione schema di convenzione (allegato A). Approvazione schema di regolamento (allegato B). L’anno DUEMILADICIANNOVE il giorno ventiquattro del mese di gennaio alle ore 18,05 presso la sala delle adunanze, si è riunito il Consiglio Comunale,convocato con avvisi spediti a termini di legge, in sessione ordinaria ed in prima convocazione. Risultano presenti/assenti i seguenti consiglieri: PIRAS MATTEO PRESENTE MOLINARO ARMANDO PRESENTE COCCO SABRINA PRESENTE PILIA PATRIK PRESENTE CUCCA PIER LUIGI PRESENTE PISU MARIA SOFIA ASSENTE CUCCA SIMONE PRESENTE PODDA MARCO PRESENTE DEMURTAS MARCO PRESENTE SCATTU FEDERICO PRESENTE LOTTO GIOVANNI PRESENTE VACCA MARCELLO PRESENTE MARCEDDU MIRCO ASSENTE Quindi n. 11 (undici) presenti su n. 13 (tredici) componenti assegnati, n. 2 (due) assenti. il Signor Matteo Piras, nella sua qualità di Sindaco, assume la presidenza e, assistito dal Segretario Comunale Dott.ssa Giovannina Busia, sottopone all'esame del Consiglio la proposta di deliberazione di cui all'oggetto, di seguito riportata: IL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE PREMESSO che: • i Comuni di Arzana, Bari Sardo, Cardedu, Elini, Ilbono, Lanusei e Loceri, con rispettive deliberazioni consiliari, si sono costituiti in Unione ai sensi dell’art. 32 del T.U.E.L. 267/2000 e dell’articolo 3 della ex Legge Regionale 12/2005 - oggi sostituita dalla Legge Regionale 2/2016 - denominandola “ Unione Comuni D’Ogliastra ” ed approvando con i medesimi atti lo Statuto e l’atto costitutivo dell’Unione; • con deliberazione del Consiglio comunale n. -

Autorizzazione Societa GLE Sport A.S.D. Per

PROVINCIA DI NUORO SETTORE INFRASTRUTTURE ZONA OMOGENEA OGLIASTRA SERVIZIO AGRICOLTURA, MANUTENZIONI E TUTELA DEL TERRITORIO DETERMINAZIONE N° 617 DEL 14/06/2019 OGGETTO: Autorizzazione societa GLE Sport A.S.D. per lo svolgimento di una competizione amatoriale e dilettantistica denominata " 8° Rally di Sardegna Bike " indetta per i giorni 16 _ 17 _ 18 _ 19 _ 20 _ 21 Giugno 2019 _ internazionale di Rally _ Raid di Mountain Bike a Tappe. IL RESPONSABILE DEL SERVIZIO VISTI: - l’art.65, comma 2, lett.B) della L.R. 9/2007 di trasferimento alla Provincia delle competenze relative al rilascio delle autorizzazioni in materia di competizioni sportive su strada; - la nota prot. 275 del 30 gennaio 2008 dell’Assessorato Regionale dei Lavori Pubblici, in base alla quale i provvedimenti autorizzativi per lo svolgimento di manifestazioni sportive su strada sono demandati alle Amministrazioni Provinciali competenti per territorio ai sensi della citata L.R. N.9/2006; - l’istanza assunta al protocollo della Provincia di Nuoro Zona Omogenea dell’Ogliastra al n. 2217 del 15/05/2019 della Società Sportiva G.L.E. Sport A.S.D., con sede in Cagliari in via Farina n° 11, a firma del suo Presidente, Sig. Gian Domenico Nieddu, per ottenere l’autorizzazione allo svolgimento di una manifestazione/gara amatoriale/dilettantistica denominata “8° Rally di Sardegna Bike” – internazionale di Rally-Raid di Mountain Bike a tappe da tenersi nei territori dei cantieri dell’Ente Forestas ricadenti nei Comuni di Arzana, Baunei, Desulo, Gairo, Orgosolo, Seui, Talana, Triei, Urzulei, Ussassai e Villagrande Strisaili nei giorni 16 – 17 – 18 – 19 – 20 – 21 Giugno 2019 . -

Silversea Silver Muse 2017

2017 – 2018 – 2019 BUONGIORNO E BENVENUTI Ever since Silversea’s early days, our principles have been rooted by our heritage. When my father Antonio, launched our first ship over 20 years ago, he advised me to keep our family values and traditions close to my heart and to not be swayed by ephemeral trends. In the ever-expanding market, it is an honour to say that it has been precisely that counsel that I have followed and that has allowed us to grow to what the company represents today: a recognised leader in luxury travel. Therefore, it is with great excitement that I introduce our newest ship, Silver Muse. Thus named, she is a divine ship; an inspirational work of art of the highest order. Boutique in size, she can visit ports that larger ships simply cannot access, yet retains an intimate, cosy, home away from home feeling. However – she is a proud ship too; large enough to offer the superlative quality of luxury service and options that we are famous for. She truly embodies our finest qualities and philosophies and is, by all definitions, the highest expression of Silversea excellence. When it comes to cruise ships, I don’t believe that bigger is better, but rather that the right size is better. A natural evolution of our sophisticated Italian design and world-renowned luxury, Silver Muse is not a total innovation, rather, we have listened to your valued feedback and modeled our newest flagship accordingly, tailor-making her to suit you. We believe that Silver Muse is quite simply, our best ship ever.