Cartographers of North Korea Who Are They and What Are the Technical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of North Korean Cyber Threats

The Evolution of North Korean Cyber Threats 2019-03 Chong Woo Kim, Senior Fellow The Asan Institute for Policy Studies Carolina Polito1 University of Bologna 2019.02.19 Introduction In North Korea, only a few people are allowed access to Kwangmyong, the national intranet service, as global internet access is restricted to a group of selected people, and the country has one of the weakest internet infrastructures in the world.2 Nonetheless, North Korea is a formidable cyber power, standing alongside major players like the United States, China, Russia, the United Kingdom, Israel and Iran.3 North Korea has been increasing resources to enhance and expand its cyber capabilities, as testified by the intensification of the regime-sponsored attacks that the world has witnessed in the last 10 years. Amongst the most blatant offensive cyber-attacks allegedly linked to hacker groups close to North Korea are the Sony Pictures attack, the WannaCry attack, and the DarkSeoul attack, despite the North’s constant denial of any involvement with these attacks or the damage suffered by them. North Korea’s cyber army consists of approximately 7,000 hackers,4 performing a wide range of activities including theft, denial of service (DDoS), espionage and sabotage. 5 These types of operations have proved to be very useful as part of North Korea’s asymmetric strategy towards the ROK-U.S. Combined Forces Command. Cyber operations are low-cost and low-risk, allowing North Korea to counter countries which have highly computer-dependent infrastructure, with little fear of retaliation. Due to their low-intensity, these attacks often lie beneath the threshold of an armed attack, reducing the risk of escalating the conflict to an unaffordable level. -

Ein Wilder Ritt Distributionen

09/2016 Besichtigungstour zu den skurrilsten Linux-Distributionen Titelthema Ein wilder Ritt Distributionen 28 Seit den frühen 90ern schießen die Linux-Distributionen wie Pilze aus dem Boden. Das Linux-Magazin blickt zurück auf ein paar besonders erstaunliche oder schräge Exemplare. Kristian Kißling www.linux-magazin.de © Antonio Oquias, 123RF Oquias, © Antonio Auch wenn die Syntax anderes vermu- samer Linux-Distributionen aufzustellen, Basis für Evil Entity denkt (Grün!), liegt ten lässt, steht der Name des klassischen denn in den zweieinhalb Jahrzehnten falsch. Tatsächlich basierte Evil Entity auf Linux-Tools »awk« nicht für Awkward kreuzte eine Menge von ihnen unseren Slackware und setzte auf einen eher düs- (zu Deutsch etwa „tolpatschig“), sondern Weg. Während einige davon noch putz- ter anmutenden Enlightenment-Desktop für die Namen seiner Autoren, nämlich munter in die Zukunft blicken, ist bei an- (Abbildung 3). Alfred Aho, Peter Weinberger und Brian deren nicht recht klar, welche Zielgruppe Als näher am Leben erwies sich der Fo- Kernighan. Kryptische Namen zu geben sie anpeilen oder ob sie überhaupt noch kus der Distribution, der auf dem Ab- sei eine lange etablierte Unix-Tradition, am Leben sind. spielen von Multimedia-Dateien lag – sie heißt es auf einer Seite des Debian-Wiki wollten doch nur Filme schauen. [1], die sich mit den Namen traditioneller Linux für Zombies Linux-Tools beschäftigt. Je kaputter, desto besser Denn, steht dort weiter, häufig halten Apropos untot: Die passende Linux- Entwickler die Namen ihrer Tools für Distribution für Zombies ließ sich recht Auch Void Linux [4], der Name steht selbsterklärend oder sie glauben, dass einfach ermitteln. Sie heißt Undead Linux je nach Übersetzung für „gleichgültig“ sie die User ohnehin nicht interessieren. -

Technology Overview New Features Backupedge

Technology Overview - BackupEDGE™ Introduction to the New Features in BackupEDGE 3.x Technology Overview BackupEDGE has a long history of providing reliable data protection for New Features many thousands of users. As operating systems, storage devices and BackupEDGE 3.x usage needs and tendencies have changed over the years, it has continuously met the challenge of providing inexpensive, stable backup and disaster recovery on a variety of UNIX and Linux platforms. Clients routinely find new and clever ways to utilize products. Storage devices have taken on new and exciting features, and incredible capacities. Products designed years ago had built-in limits that were thought to be beyond comprehension. Today, these limits are routinely exceeded. The need for data security is even more apparent. We’re constantly asking our To continue to meet the evolving needs of our clients, we are always clients what tools our asking what features of our products they find most useful, what products need to serve them improvements we can make, and what new requirements they have. better. We’ve used this knowledge to map out new product strategies designed to anticipate the needs of the next generation of users, systems and storage products. This has resulted in the creation of BackupEDGE 3.x, with a combination of internal improvements, new features and enhanced infrastructure designed to become the backbone of a new generation of storage software. Summary of Major Changes and Additions BackupEDGE 3.x features include: • Improvements to partition sizing, UEFI table cleanup after DR, and SharpDrive debugging (03.04.01 build 3). • Support for Rocky Linux 8.4 and AlmaLinux 8.4 (03.04.01 build 2). -

Governmental Control of Digital Media Distribution in North Korea: Surveillance and Censorship on Modern Consumer Devices

Governmental Control of Digital Media Distribution in North Korea: Surveillance and Censorship on Modern Consumer Devices Niklaus Schiess ERNW GmbH Abstract pressive regimes like China [14], Iran [7] or Turkey [6] are using national telecommunication networks as an in- Modern devices like PCs and tablet PCs enable users strument to interfere with information flows within their to consume a wide range of media like videos, audio country and even across borders [13]. In the case of and documents. Introducing such devices in repressive North Korea, which is considered one of the most repres- regimes like North Korea [10] (officially Democratic sive states [11], where typical users only get access to a People’s Republic of Korea, DPRK) contradicts the ob- nationwide intranet that is entirely controlled by the gov- jective of controlling and suppressing information within ernment. Full Internet access, without any governmental the country and particularly information imported from regulations and restrictions of the consumable content, is the outside world. This can be generalized as any in- only possible for a chosen few [12]. formation that has not been reviewed and approved by the government. This paper is an effort to evaluate the technical challenges that arise while enabling users to 1.1 Motivation consume or create potentially unwanted media and an- Although network-level control over media distribution alyzes two media-controlling mechanisms developed by can be effective even on a nationwide scale, the effec- North Korean government organizations. The analysis tiveness is limited in a technical less advanced environ- covers implementations found in Red Star OS, a Linux- ment like North Korea today [11]. -

An Assessment of North Korean Threats and Vulnerabilities in Cyberspace

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2017 An Assessment of North Korean Threats and Vulnerabilities in Cyberspace Jeremiah van Rossum Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons Recommended Citation van Rossum, Jeremiah, "An Assessment of North Korean Threats and Vulnerabilities in Cyberspace" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3212. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3212 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ASSESSMENT OF NORTH KOREAN THREATS AND VULNERABILITIES IN CYBERSPACE A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Jeremiah Adam van Rossum December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Jeremiah Adam van Rossum ii AN ASSESSMENT OF NORTH KOREAN THREATS AND VULNERABILITIES IN CYBERSPACE Defense and Strategic Studies Missouri State University, December 2017 Master of Science Jeremiah Adam van Rossum ABSTRACT This thesis answers the fundamental questions of what North Korean capabilities and intent in cyberspace are and what North Korean threats and vulnerabilities are associated with these. -

Cornell International Affairs Review

ISSN 2156-0536 C ORNELL I NTERNAT I ONAL A ffA I RS R E vi EW VOLUME V | ISSUE I | FALL 2011 When Should the US Intervene? The Cornell International Affairs Review is a student-run organization aiming to provide an Criteria for Intervention in Weak Countries international, intergenerational, and interdisciplinary approach to foreign affairs. Robert Keohane, Professor of International Affairs Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University Letter from Tunisia Founded in 2006, the CIAR is proud to provide the Cornell community with a semesterly Elyès Jouini, Professor and Vice-President, Université Paris-Dauphine review, bringing together views from students, professors, and policymakers on the current Former Minister for the Economic and Social Reforms, Tunisian Transition Government events shaping our world. Empowering Women in the Chinese Capitalist Factory System Sara Akl, University of Virginia, 2013 It is our firm belief that true knowledge stems not just from textbooks and lectures but from The Problems with American Exceptionalism engaging with others. Thus, the CIAR strongly emphasizes cooperation and dialogue amongst Timothy Borjian, University of California, Berkeley, 2012 all our members, both on Cornell’s campus and beyond. The Evolution of Revolution: Social Media in the Modern Middle East and its Policy Implications Taylor Bossung, Indiana University, 2012 Brazil’s China Challenge Carlos Sucre, MA Candidate, George Washington University Information Technology and Control in the DPRK Robert Duffley, Georgetown University, 2013 The Illusion of US Isolationism Eugenio Lilli, King’s College, London, Postgraduate Researcher, Teaching Fellow at the Defense Studies Department, UK Joint Services Command and Staff College Militarization of Aid and its Implications for Colombia Ian King, U.S. -

Blas, Zach. 2016. Contra-Internet. E-Flux Journal, 74, ISSN 2164-1625

Blas, Zach. 2016. Contra-Internet. e-flux journal, 74, ISSN 2164-1625 [Article] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/18595/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] Zach Blas 1 of 5 e-flux journal #74 (2016) CONTRA-INTERNET 1. Killing the Internet On January 28th, 2011, only a few days after protests had broken out in Egypt demanding the overthrow of then President Hosni Mubarak, the Egyptian government terminated national access to the internet. This state-sponsored shutdown became known as flipping the internet’s“kill switch.” Intentions motivating the killing of the internet in Egypt were to block protestors from coordinating with one another and the dissemination of any media about the uprising, especially to those outside of the country. Peculiarly, it is a death that only lasted five days, as internet access was soon reinstated. More precisely, the internet kill switch unfolded as a series of political demands and technical operations. Egyptian Internet Service Providers, such as Telecom Egypt, Raya, and Link Egypt, were ordered to cancel their routing services, which had the effect of stymying internet connectivity through these major companies. -

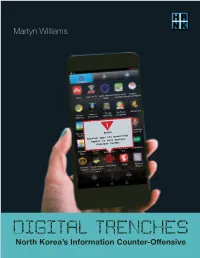

Digital Trenches

Martyn Williams H R N K Attack Mirae Wi-Fi Family Medicine Healthy Food Korean Basics Handbook Medicinal Recipes Picture Memory I Can Be My Travel Weather 2.0 Matching Competition Gifted Too Companion ! Agricultural Stone Magnolia Escpe from Mount Baekdu Weather Remover ERRORTelevision the Labyrinth Series 1.25 Foreign apps not permitted. Report to your nearest inminban leader. Business Number Practical App Store E-Bookstore Apps Tower Beauty Skills 2.0 Chosun Great Chosun Global News KCNA Battle of Cuisine Dictionary of Wisdom Terms DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive Copyright © 2019 Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior permission of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 435 Washington, DC 20036 P: (202) 499-7970 www.hrnk.org Print ISBN: 978-0-9995358-7-5 Digital ISBN: 978-0-9995358-8-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019919723 Cover translations by Julie Kim, HRNK Research Intern. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gordon Flake, Co-Chair Katrina Lantos Swett, Co-Chair John Despres, -

Monday, November 28, 2016 the Opening of the North Korean Mind Pyongyang Versus the Digital Underground Jieun Baek

12/2/2016 The Opening of the North Korean Mind Home > The Opening of the North Korean Mind Monday, November 28, 2016 The Opening of the North Korean Mind Pyongyang Versus the Digital Underground Jieun Baek JIEUN BAEK is the author of North Korea’s Hidden Revolution: How the Information Underground Is Transforming a Closed Society (Yale University Press, 2016), from which this essay is adapted. From 2014 to 2016, she was a Fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University. Follow her on Twitter @JieunBaek1. On a cold, clear night in September 2014, a man I’ll call Ahn walked up to the edge of the Tumen River on the Chinese side of the heavily guarded border between China and North Korea. At its narrowest points, the Tumen measures a little over 150 feet wide, and Ahn could easily see the North Korean side from where he stood. In two bags, he was carrying 100 USB drives filled with films, television shows, music, and ebooks from around the world. Almost anywhere else, such material would be considered completely innocuous. At this border, however, it constitutes highly illicit, dangerous contraband. In the totalitarian state of North Korea, citizens are allowed to see and hear only those media products created or sanctioned by the government. Pyongyang considers foreign information of any kind a threat and expends great effort keeping it out. The regime’s primary fear is that exposure to words, images, and sounds from the outside world could make North Koreans disillusioned with the state of affairs in their own country, which could lead them to desire—or even demand—change. -

Current Affairs in North Korea, 2010-2017: a Collection of Research Notes

235 Current Affairs in North Korea, 2010-2017: A Collection of Research Notes Rudiger Frank Abstract Starting with the public introduction of Kim Jong-un to the public in autumn of 2010 and ending with observations of consumerism in February 2017, this collection of 16 short research notes that were originally published at 38North discusses some of the most crucial issues, aside from the nuclear problem, that dominated the field of North Korean Studies in the past decade. Left in their original form, these short articles show the consistency of major North Korean policies as much as the development of our understanding of the new leader and his approach. Topics covered include the question of succession, economic statistics, new ideological trends such as pyŏngjin, techno- logical developments including a review of the North Korean tablet computer Samjiyŏn, the Korean unification issue, special economic zones, foreign trade, parliamentary elections and the first ever Party congress since 1980. Keywords: North Korea, DPRK, 38North Frank, Rudiger. “Current Affairs in North Korea, 2010-2017: A Collection of Research Notes” In Vienna Journal of East Asian Studies, Volume 9, eds. Rudiger Frank, Ina Hein, Lukas Pokorny, and Agnes Schick-Chen. Vienna: Praesens Verlag, 2017, pp. 235–350. https://doi.org/10.2478/vjeas-2017-0008 236 Vienna Journal of East Asian Studies Hu Jintao, Deng Xiaoping or another Mao Zedong? Power Restruc- turing in North Korea Date of original publication: 5 October 2010 URL: http://38north.org/2010/10/1451 “Finally,” one is tempted to say. The years of speculation and half-baked news from dubious sources are over. -

The Koreas and the Policy/Culture Nexus

Two States, One Nation: The Koreas and the Policy/Culture Nexus Jacqueline Willis Institute for Culture and Society University of Western Sydney A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. © 2013 Acknowledgements I would like to especially thank my principal supervisor Professor James Arvanitakis for the unfailing guidance, encouragement and support he has given me throughout my candidature. His academic expertise, enthusiasm and assuring presence have provided the motivation, confidence and direction needed to complete this intellectually stimulating, though sometimes daunting task. I gratefully acknowledge and extend immeasurable thanks for his mentorship, editorship and invaluable feedback, without which this thesis could not have been written. I would also like to acknowledge the input of my co-supervisor Professor Brett Neilson, whose expert knowledge and recommendations have proven invaluable to the development and completion of this thesis. Special thanks and acknowledgement must also be given to Shin Yoon Ju for providing Korean-English translations, as well as to Brian J. McMorrow, Grete Howard, Eric Testroete, Chris Wood, Raymond Cunningham and fellow Korea researcher, Christopher Richardson, for generously allowing me to use and reproduce their personal photographs. Thanks too to those affiliated with the Institute for Culture and Society at the University of Western Sydney, for their committed nurturing of my academic development and ambitions over the course of my doctoral enrolment. Finally, I would like to extend gratitude to my family, friends and colleagues for always encouraging me in my academic endeavours. Their patience, unwavering support and steadfast faith in my ability have been powerful incentives, driving and sustaining me in my scholarly pursuits. -

The Dprk As an Example of the Potential Utility of Internet Sanctions

\\server05\productn\B\BIN\25-1\BIN104.txt unknown Seq: 1 31-MAR-08 10:18 USING INTERNET “BORDERS” TO COERCE OR PUNISH: THE DPRK AS AN EXAMPLE OF THE POTENTIAL UTILITY OF INTERNET SANCTIONS BENJAMIN BROCKMAN-HAW E * INTRODUCTION ................................................... 163 R I. BACKGROUND INFORMATION .............................. 166 R A. Escalation ............................................. 167 R B. The Internet in North Korea ........................... 173 R II. SANCTIONS ................................................ 181 R A. General Information ................................... 182 R B. Telecommunications Sanctions Already Considered .... 184 R C. Multilateral Sanctions In Place Against the DPRK ..... 187 R III. THE UTILITY OF INTERNET SANCTIONS .................... 187 R A. Obtaining a desired result through the imposition of Internet sanctions ...................................... 187 R B. The Benefits and Costs of Imposing Internet Sanctions . 198 R C. General Concerns Associated with the Use of Internet Sanctions .............................................. 200 R 1. International Human Rights ....................... 200 R 2. Internet sanctions could harm regime opponents . 203 R 3. Internet sanctions could impair the ability of UN operations and NGO’s to function within the target country ..................................... 204 R IV. CONCLUSION .............................................. 205 R INTRODUCTION Speech is civilization itself. The word. preserves contact—it is silence which isolates. - Thomas Mann1 * J.D. Candidate 2008, Boston University School of Law. This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Robert Brockman, a man who surveyed this new world with the eyes of an old soul. 1 THOMAS MANN, THE MAGIC MOUNTAIN (1924) quoted in CHARLES R. BURGER & JAMES J. BRADAC, LANGUAGE AND SOCIAL KNOWLEDGE 112 (Edward Arnold Publishers Ltd. 1982). 163 \\server05\productn\B\BIN\25-1\BIN104.txt unknown Seq: 2 31-MAR-08 10:18 164 BOSTON UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol.