Berlin DADA: a Few Remarks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before Zen: the Nothing of American Dada

Before Zen The Nothing of American Dada Jacquelynn Baas One of the challenges confronting our modern era has been how to re- solve the subject-object dichotomy proposed by Descartes and refined by Newton—the belief that reality consists of matter and motion, and that all questions can be answered by means of the scientific method of objective observation and measurement. This egocentric perspective has been cast into doubt by evidence from quantum mechanics that matter and motion are interdependent forms of energy and that the observer is always in an experiential relationship with the observed.1 To understand ourselves as in- terconnected beings who experience time and space rather than being sub- ject to them takes a radical shift of perspective, and artists have been at the leading edge of this exploration. From Marcel Duchamp and Dada to John Cage and Fluxus, to William T. Wiley and his West Coast colleagues, to the recent international explosion of participatory artwork, artists have been trying to get us to change how we see. Nor should it be surprising that in our global era Asian perspectives regarding the nature of reality have been a crucial factor in effecting this shift.2 The 2009 Guggenheim exhibition The Third Mind emphasized the im- portance of Asian philosophical and spiritual texts in the development of American modernism.3 Zen Buddhism especially was of great interest to artists and writers in the United States following World War II. The histo- ries of modernism traced by the exhibition reflected the well-documented influence of Zen, but did not include another, earlier link—that of Daoism and American Dada. -

Machine Head: Raoul Hausmann and the Optophone Author(S): Jacques Donguy Source: Leonardo, Vol

Machine Head: Raoul Hausmann and the Optophone Author(s): Jacques Donguy Source: Leonardo, Vol. 34, No. 3 (2001), pp. 217-220 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1576938 Accessed: 02-08-2018 18:51 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Leonardo This content downloaded from 158.223.165.42 on Thu, 02 Aug 2018 18:51:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Machine Head: Raoul Hausmann and the Optophone Jacques Donguy In his initial text on his invention the Opto- I gave a technical explanation of A B S T R A C T phone, published in 1922, Dadaist Raoul Hausmann de- the Optophone. I still have a copy scribed "space-time" as the sixth and "most important of our of this issue in my possession. Dadaist Raoul mann, Hausi In 1927 I1 was visited by the engi- famous for his photomont senses." (We should recall that Einstein formulated his spe- tages, is neer Daniel Broido [3], who was perhaps less well known as a pio- a cial theory of relativity, which conceives of time as the fourth working on a photoelectric calcu- neer of synaesthetic hines de-macl dimension of space [1], in 1905, and that the general theory lating machine for a big electricity signed to transform d into sound of relativity describes matter as a bend in "space-time"). -

1 Hanne Bergius "JOIN DADA!"

Hanne Bergius "JOIN DADA!" ASPECTS OF DADA`S RECEPTION SINCE THE LATE 1950S Lecture for the symposium "Representing Dada", September 9, 2006 in the Museum`s Titus 1 Theater, 11 West 53rd Street, New York held in conjunction with the exhibition "Dada ", on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (June 18 - September 11,2006) I thank you for your invitation and I am delighted to talk to you in the context of this exhibition, which would also have made sense in Germany. The last one took place in 1994 and presented above all the Dada collection of the Kunsthaus Zürich. (1) When we now examine some aspects of Dada`s reception since the late 1950s, let us focus on two dada exhibitions: 1958 in Düsseldorf and 1977 in Berlin. They were the most important international Dada retrospectives in Germany since the " First International Dada Fair" of the Berlin Dadaists in 192o ( - beside one exhibition in 1966 which showed only documents.(2)) If "Dada. Documents of a Movement "(3) at Düsseldorf stood in the context of Neo-Dada, "Dada in Europe. Documents and Works"(4) was integrated into the larger "Tendencies of the Twenties" project as the 15th exhibition of the European Council in Berlin.(5). As the Cover of the Exhibition Catalogue of the "Tendencies of the Twenties" (1977) (Fig. 1) shows in addition to Dada , sections on Surrealism/New Objectivity, Constructivism and Architecture of the Twenties were also included. It was a very succesfull exhibition, by which Berlin capitalized in particular on the most exciting chapter in its history - the "Roaring Twenties". -

'Kurt Schwitters in England', Baltic, No 4, Gateshea

1 KURT SCHWITTERS IN ENGLAND, Sarah Wilson, Courtauld Institute of Art, ‘Kurt Schwitters in England', Baltic, no 4, Gateshead, np, 1999 (unfootnoted version); ‘Kurt Schwitters en Inglaterra el "Anglismo" o la dialéctica del exilio’, Kurt Schwitters, IVAM Centre Julio González, Valencia, pp. 318-335, 1995 ‘Kurt Schwitters en Angleterre’, Kurt Schwitters, retrospective, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, pp. 296-309 `ANGLISM': THE DIALECTICS OF EXILE' Three orthodoxies have dictated previous accounts of the life of Kurt Schwitters in England: that England was simply `exile', a cultural desert, that he was lonely, unappreciated, that his late figurative work is too embarrassing to be displayed in any authoritative retrospective. Scholars ask `What if?' What if Schwitters had got a passport to United States and had joined other artists in exile? He would have continued making Merz with American material. He would have had no `need' to paint figuratively.1 Would he have fitted his past into an even more `modernist' mould like his friend Naum Gabo, to please the New Yorkers?2 Surely not. `Emigration is the best school of dialectics' declared Bertold Brecht.3 Schwitters' last period must be investigated not in terms of `exile' but the dialectics of exile: as a future which cuts off a past which lives on through it all the more intensely in memory, repetition, recreation. `Exile' moreover is a purely negative term, foreclosing all the inspirational possibilities of a new `genius loci', a spirit of place: England. The Germany Schwitters knew was disfigured, disintegrating, self-destructing. His longing was for place which was no more. His Merzbau was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1943; Helma died in 1944: `Hanover a heap of ruins, Berlin destroyed, and you're not allowed to say how you feel.'4 The English period was a both a death and a birth, a question of identity through time, of new and old languages. -

In and Around Duchamp (New York Dada)

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D/CI) Spring 2012 Professor Caroline A. Jones Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section. Department of Architecture Lecture 13 PRODUCTION AND (COMMODITY) FETISH: Lecture 13: In and around Duchamp (New York Dada) "Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view - created a new thought for that object." - Beatrice Wood (and M.D.), The Blind Man 1917 I. European Dada and artistic agency under Fascism A. Heartfield vs. Schwitters B. Agitation through propaganda, or internal exile and the “safehouse” of art? II. New York New York (so nice they named it twice) A. Metaphor for heedless modernity, crass materialism, vertiginous disorientation, new modes of performative subjectivity (gender-bending, mechanical, neurasthenic) B. Untrammeled space for contests over modernism- a style (Picassoid Cubism; Futurism), or a conceptual attitude (Duchampian performance)? C. Site for the 1913 Armory Show- its extraordinary impact on U.S. artists D. Site for the “Independents” and their International Painting and Sculpture exhibition, 1917 - birth of the Blind Man and “Fountain” III. Dada in New York (an activity in NY before the naming in Zurich in 1916) A. Francis Picabia -1913 visit, 1915 visit (AWOL), 1917 visit, arrived in NY on the very day US entered the first World War B. Marcel Duchamp - 1915 to New York, helps found “Société Anonyme” (a first, private, Museum of Modern Art) in 1920, back and forth between NY and Paris in the 20s, “stops making art” in 1930s (Surrealist exhibitions), moves permanently to US in 40s, lionized in 1960s as “Dada-daddy,” in 1980s as “father” of Postmodernism C. -

Biblioteca Di Studi Di Filologia Moderna – 37 –

BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI DI FILOLOGIA MODERNA – 37 – DIPARTIMENTO DI LINGUE, LETTERATURE E STUDI INTERCULTURALI Università degli Studi di Firenze Coordinamento editoriale Fabrizia Baldissera, Fiorenzo Fantaccini, Ilaria Moschini Donatella Pallotti, Ernestina Pellegrini, Beatrice Töttössy BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI DI FILOLOGIA MODERNA Collana Open Access del Dipartimento di Lingue, Letterature e Studi Interculturali Direttore Beatrice Töttössy Comitato scientifico internazionale Enza Biagini (Professore Emerito), Nicholas Brownlees, Martha Canfield, Richard Allen Cave (Emeritus Professor, Royal Holloway, University of London), Piero Ceccucci, Massimo Ciaravolo (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia), John Denton, Anna Dolfi, Mario Domenichelli (Professore Emerito), Maria Teresa Fancelli (Professore Emerito), Massimo Fanfani, Fiorenzo Fantaccini (Università degli Studi di Firenze), Paul Geyer (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn), Ingrid Hennemann, Sergej Akimovich Kibal’nik (Institute of Russian Literature [the Pushkin House], Russian Academy of Sciences; Saint-Petersburg State University), Ferenc Kiefer (Research Institute for Linguistics of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences; Academia Europaea), Michela Landi, Murathan Mungan (scrittore), Stefania Pavan, Peter Por (CNRS Parigi), Gaetano Prampolini, Paola Pugliatti, Miguel Rojas Mix (Centro Extremeño de Estudios y Cooperación Iberoamericanos), Giampaolo Salvi (Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest), Ayşe Saraçgil, Rita Svandrlik, Angela Tarantino (Università degli Studi di Roma ‘La Sapienza’), Maria -

Marcel Janco in Zurich and Bucharest, 1916-1939 a Thesis Submi

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Between Dada and Architecture: Marcel Janco in Zurich and Bucharest, 1916-1939 A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Adele Robin Avivi June 2012 Thesis Committee: Dr. Susan Laxton, Chairperson Dr. Patricia Morton Dr. Éva Forgács Copyright by Adele Robin Avivi 2012 The Thesis of Adele Robin Avivi is approved: ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Special thanks must first go to my thesis advisor Dr. Susan Laxton for inspiring and guiding my first exploration into Dada. This thesis would not have been possible without her enthusiastic support, thoughtful advice, and careful reading of its many drafts. Thanks are also due to Dr. Patricia Morton for her insightful comments that helped shape the sections on architecture, Dr. Éva Forgács for generously sharing her knowledge with me, and Dr. Françoise Forster-Hahn for her invaluable advice over the past two years. I appreciate the ongoing support and helpful comments I received from my peers, especially everyone in the thesis workshop. And thank you to Danielle Peltakian, Erin Machado, Harmony Wolfe, and Sarah Williams for the memorable laughs outside of class. I am so grateful to my mom for always nourishing my interests and providing me with everything I need to pursue them, and to my sisters Yael and Liat who cheer me on. Finally, Todd Green deserves very special thanks for his daily doses of encouragement and support. His dedication to his own craft was my inspiration to keep working. -

Dadaist Manifesto by Tristan Tzara, Franz Jung, George Grosz, Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Gerhard Preisz, Raoul Hausmann April 1918

dadaist manifesto by tristan tzara, franz jung, george grosz, marcel janco, richard huelsenbeck, gerhard preisz, raoul hausmann april 1918 Dadaist Manifesto (Berlin) The signatories of this manifesto have, under the battle cry DADA!!!! gathered together to put forward a new art from which they expect the realisation of new ideas. So what is DADAISM, then? The word DADA symbolises the most primitive relationship with the surrounding reality; with Dadaism, a new reality comes into its own. Life is seen in a simultaneous confusion of noises, colours and spiritual rhythms which in Dadaist art are immediately captured by the sensational shouts and fevers of its bold everyday psyche and in all its brutal reality. This is the dividing line between Dadaism and all other artistic trends and especially Futurism which fools have very recently interpreted as a new version of Impressionism. For the first time, Dadaism has refused to take an aesthetic attitude towards life. It tears to pieces all those grand words like ethics, culture, interiorisation which are only covers for weak muscles. THE BRUITIST POEM describes a tramcar exactly as it is, the essence of a tramcar with the yawns of Mr Smith and the shriek of brakes. THE SIMULTANEOUS POEM teaches the interrelationship of things, while Mr Smith reads his paper, the Balkan express crosses the Nisch bridge and a pig squeals in the cellar of Mr Bones the butcher. THE STATIC POEM turns words into individuals. The letters of the word " wood " create the forest itself with the leafiness of its trees, the uniforms of the foresters and the wild boar. -

Dada-Guide-Booklet HWB V5.Pdf

DA DA DA DA THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA LIBRARIES PRESENTS DOCUMENTING DADA // DISSEMINATING DADA THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA LIBRARIES MAIN LIBRARY GALLERY JANUARY 17 - APRIL 28, 2017 An exhibition featuring items from the UI Libraries' International DADA Archive, the world’s most comprehensive collection of material related to the Dada movement. GALLERY HOURS & COMPLETE EXHIBITION INFORMATION AT LIB.UIOWA.EDU/GALLERY EXHIBITION GUIDE 1 DOCUMENTING DADA // DISSEMINATING DADA From 1916 to 1923, a new kind of artistic movement Originating as an anti-war protest in neutral swept Europe and America. Its very name, “DADA” Switzerland, Dada rapidly spread to many corners —two identical syllables without the obligatory of Europe and beyond. The Dada movement was “-ism”—distinguished it from the long line of avant- perhaps the single most decisive influence on the gardes that had determined the preceding century of development of twentieth-century art, and its art history. More than a mere art movement, Dada innovations are so pervasive as to be virtually taken claimed a broader role as an agent of cultural, social, for granted today. and political change. This exhibition highlights a single aspect of Dada: Its proponents came from all parts of Europe and the its print publications. Since the essence of Dada was United States at a time when their native countries best reflected in ephemeral performances and actions were battling one another in the deadliest war ever rather than in concrete artworks, it is perhaps ironic known. They did not restrict themselves to a single that the dadaists produced many books and journals mode of expression as painter, writer, actor, dancer, of astonishing beauty. -

Theo Van Doesburg Archive

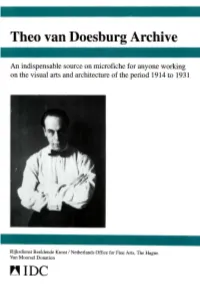

TheoTheo vavann DoesburgDoesburg ArchiveArchive AnAn indispensableindispensable sourcesource onon microfichemicrofiche forfor anyoneanyone workingworking oonn ththee visualvisual artsarts andand architecturearchitecture ofof thethe periodperiod 19141914 toto 19311931 RijksdienstRijksdienst BeeldendeBeeldende KunstKunst // NetherlandsNetherlands Office Office forfor FineFine Arts,Arts, TheThe HagueHague VanVan MoorseMoorsell DonationDonation H!IIDC IDC TheTheoo vavann DoeDoesbur sburgg ArchivArchivee AnAn indispensableindispensable sourcesource onon microfichemicrofiche forfor anyonanyonee workinworkingg oonn ththee visualvisual artsarts anandd architecturarchitecturee ofof thethe periodperiod 19141914 toto 19311931 TheTheoo vavann DoesburDoesburgg (1883-1931(1883-1931)) waswas a ΑφArp,, VaVann EesterenEesteren,, GropiusGropius,, Huszar,Huszar, InIn addition,addition, thethe archivearchive containscontains somesome painterpainter,, architectarchitect,, arartt theoreticiatheoreticiann andand artart VaVann dederr LeckLeek,, LissitzkyLissitzky,, Mondriaan,Mondriaan, importanimportantt 'recovered'recovered'' correspondencecorrespondence criticcritic,, typographertypographer,, writer,writer, andand poet.poet. InIn OudOud,, Rietveld,Rietveld, Schwitters,Schwitters, TzarTzaraa andand fromfrom VanVan DoesburDoesburgg himself:himself: lettersletters toto 19171917 hhee foundefoundedd ththee magazinmagazinee DeDe StijiStijl many,many, manmanyy others)others);; VanVan Doesburg'sDoesburg's hishis friendsfriends Kok,Kok, OudOud andand Rinsema.Rinsema. -

1 Dada Origins 1 2 Marcel Duchamp 14 3 Höch and Hausmann 28 4 Kurt

GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / DADA / OVerVIEW I / lV Dada 1 Dada Origins 1 2 Marcel Duchamp 14 3 Höch and Hausmann 28 4 Kurt Schwitters 38 5 Dada Legacy 56 6 Conclusion 63 © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / DADA / JaponIsme II / lV © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / DADA 1 / 55 Dada Origins 1916–1922 Dadaism is a cultural movement that began in Zurich, Switzerland, during World War I. © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / DADA / ORIGIns 2 / 55 1916–1922 Dada Philosophy Rejecting all tradition, they sought complete freedom. They bitterly rebelled against the horrors of war, the decadence of European society, the shallowness of blind faith in technological progress, and the inadequacy of religion and conventional moral codes in a continent in upheaval. –MEGGS · © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 · GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / DADA / ORIGIns 3 / 55 1916–1922 Dada Philosophy • Reaction to the carnage of World War I • Claimed to be anti-art • Had a negative and destructive element © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 RAOUL HAUSMANN, MECHANICAL HEAD (THE SPIRIT OF OUR TIME), ASSEMBLAGE CIRCA 1920 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / DADA / ORIGIns 4 / 55 1916–1922 Dada Philosophy • Literature • Poetry • Visual Arts • Manifestoes • Theatre • Graphic design • Art theory © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / DADA / ORIGIns 5 / 55 1916–1922 Dada Activities Dada writers and artists were concerned with: • Shock • Protest • Nonsense • Obsurdity • Confrontation © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 DADAISTS IN DISGUISE, ANDRÉ BRETON, RENÉ HILSUM (STANDING), LOUIS ARAGON, PAUL ÉLUARD GDT-101 / HISTORY OF GRAPHIC DESIGN / DADA / ORIGIns 6 / 55 1916–1922 Dada Activities • Public gatherings • Demonstrations • Publication of art/literary journals • Art and political criticism © KEVIN WOODLAND, 2015 DADAISTS AT THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL DADA FAIR IN BERLIN IN 1920. -

Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: the Avant-Garde, No

NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J BATA LIBRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/raoulhausmannberOOOObens Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: The Avant-Garde, No. 55 Stephen C. Foster, Series Editor Associate Professor of Art History University of Iowa Other Titles in This Series No. 47 Artwords: Discourse on the 60s and 70s Jeanne Siegel No. 48 Dadaj Dimensions Stephen C. Foster, ed. No. 49 Arthur Dove: Nature as Symbol Sherrye Cohn No. 50 The New Generation and Artistic Modernism in the Ukraine Myroslava M. Mudrak No. 51 Gypsies and Other Bohemians: The Myth of the Artist in Nineteenth- Century France Marilyn R. Brown No. 52 Emil Nolde and German Expressionism: A Prophet in His Own Land William S. Bradley No. 53 The Skyscraper in American Art, 1890-1931 Merrill Schleier No. 54 Andy Warhol’s Art and Films Patrick S. Smith Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada by Timothy O. Benson T TA /f T Research U'lVlT Press Ann Arbor, Michigan \ u » V-*** \ C\ Xv»;s 7 ; Copyright © 1987, 1986 Timothy O. Benson All rights reserved Produced and distributed by UMI Research Press an imprint of University Microfilms, Inc. Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Benson, Timothy O., 1950- Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada. (Studies in the fine arts. The Avant-garde ; no. 55) Revision of author’s thesis (Ph D.)— University of Iowa, 1985. Bibliography: p. Includes index. I. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Aesthetics. 2. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Political and social views.