Cell Structure and Function in Bacteria and Archaea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Methanosarcina Barkeri Genome

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Title The Methanosarcina barkeri genome: comparative analysis with Methanosarcina acetivorans and Methanosarcina mazei reveals extensive rearrangement within methanosarcinal genomes Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3g16p0m7 Authors Maeder, Dennis L. Anderson, Iain Brettin, Thomas S. et al. Publication Date 2006-05-19 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LBNL-60247 Preprint Title: The Methanosarcina barkeri genome: comparative analysis with Methanosarcina acetivorans and Methanosarcina mazei reveals extensive rearrangement within methanosarcinal genomes Author(s): Dennis L. Maeder, Iain Anderson, et al Division: Genomics November 2006 Journal of Bacteriology Maeder et al. May 18, 2006 1 2 The Methanosarcina barkeri genome: comparative analysis 3 with Methanosarcina acetivorans and Methanosarcina mazei 4 reveals extensive rearrangement within methanosarcinal 5 genomes 6 7 8 9 Dennis L. Maeder*, Iain Anderson†, Thomas S. Brettin†, David C. Bruce†, Paul Gilna†, 10 Cliff S. Han†, Alla Lapidus†, William W. Metcalf‡, Elizabeth Saunders†, Roxanne 11 Tapia†, and Kevin R. Sowers*. 12 13 * University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute, Center of Marine Biotechnology, 14 Columbus Center, Suite 236, 701 E. Pratt St., Baltimore, Maryland 21202, USA 15 † Microbial Genomics, DOE Joint Genome Institute, 2800 Mitchell Drive, B400, Walnut 16 Creek, CA 94598, USA 17 ‡ University of Illinois, Department of Microbiology, B103 Chemical and Life Sciences 18 Laboratory, 601 S. Goodwin Avenue, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA 19 20 Running title: Comparative analysis of three methanosarcinal genomes 21 22 Keywords: Methanosarcina barkeri, archaeal genome, methanogenic Archaea 1 Maeder et al. May 18, 2006 23 ABSTRACT 24 25 We report here a comparative analysis of the genome sequence of 26 Methanosarcina barkeri with those of Methanosarcina acetivorans and 27 Methanosarcina mazei. -

Advanced Morphometric Techniques Applied to The

UNIVERSIDAD POLITÉCNICA DE MADRID ESCUELA TÉCNICA SUPERIOR DE INGENIEROS DE TELECOMUNICACIÓN ADVANCED MORPHOMETRIC TECHNIQUES APPLIED TO THE STUDY OF HUMAN BRAIN ANATOMY TESIS DOCTORAL Yasser Alemán Gómez Ingeniero en Tecnologías Nucleares y Energéticas Máster en Neurociencias Madrid, 2015 DEPARTAMENTO DE INGENIERÍA ELECTRÓNICA ESCUELA TÉCNICA SUPERIOR DE INGENIEROS DE TELECOMUNICACIÓN PHD THESIS ADVANCED MORPHOMETRIC TECHNIQUES APPLIED TO THE STUDY OF HUMAN BRAIN ANATOMY AUTHOR Yasser Alemán Gómez Ing. en Tecnologías Nucleares y Energéticas MSc en Neurociencias ADVISOR Manuel Desco Menéndez, MScE, MD, PhD Madrid, 2015 Departamento de Ingeniería Electrónica Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros de Telecomunicación Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Ph.D. Thesis Advanced morphometric techniques applied to the study of human brain anatomy Tesis doctoral Técnicas avanzadas de morfometría aplicadas al estudio de la anatomía cerebral humana Author: Yasser Alemán Gómez Advisor: Manuel Desco Menéndez Committee: Andrés Santos Lleó Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain Javier Pascau Gonzalez-Garzón Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Madrid, Spain Raymond Salvador Civil FIDMAG – Germanes Hospitalàries, Barcelona, Spain Pablo Campo Martínez-Lage Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain Juan Domingo Gispert López Universidad Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain María Jesús Ledesma Carbayo Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain Juan José Vaquero López Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Madrid, Spain Esta Tesis ha sido desarrollada en el Laboratorio de Imagen Médica de la Unidad de Medicina y Cirugía Experimental del Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Gregorio Marañón y en colaboración con el Servicio de Psiquiatría del Niño y del Adolescente del Departamento de Psiquiatría del Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón de Madrid, España. Tribunal nombrado por el Sr. -

Phylogenomic Networks Reveal Limited Phylogenetic Range of Lateral Gene Transfer by Transduction

The ISME Journal (2017) 11, 543–554 OPEN © 2017 International Society for Microbial Ecology All rights reserved 1751-7362/17 www.nature.com/ismej ORIGINAL ARTICLE Phylogenomic networks reveal limited phylogenetic range of lateral gene transfer by transduction Ovidiu Popa1, Giddy Landan and Tal Dagan Institute of General Microbiology, Christian-Albrechts University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany Bacteriophages are recognized DNA vectors and transduction is considered as a common mechanism of lateral gene transfer (LGT) during microbial evolution. Anecdotal events of phage- mediated gene transfer were studied extensively, however, a coherent evolutionary viewpoint of LGT by transduction, its extent and characteristics, is still lacking. Here we report a large-scale evolutionary reconstruction of transduction events in 3982 genomes. We inferred 17 158 recent transduction events linking donors, phages and recipients into a phylogenomic transduction network view. We find that LGT by transduction is mostly restricted to closely related donors and recipients. Furthermore, a substantial number of the transduction events (9%) are best described as gene duplications that are mediated by mobile DNA vectors. We propose to distinguish this type of paralogy by the term autology. A comparison of donor and recipient genomes revealed that genome similarity is a superior predictor of species connectivity in the network in comparison to common habitat. This indicates that genetic similarity, rather than ecological opportunity, is a driver of successful transduction during microbial evolution. A striking difference in the connectivity pattern of donors and recipients shows that while lysogenic interactions are highly species-specific, the host range for lytic phage infections can be much wider, serving to connect dense clusters of closely related species. -

A Korarchaeal Genome Reveals Insights Into the Evolution of the Archaea

A korarchaeal genome reveals insights into the evolution of the Archaea James G. Elkinsa,b, Mircea Podarc, David E. Grahamd, Kira S. Makarovae, Yuri Wolfe, Lennart Randauf, Brian P. Hedlundg, Ce´ line Brochier-Armaneth, Victor Kunini, Iain Andersoni, Alla Lapidusi, Eugene Goltsmani, Kerrie Barryi, Eugene V. Koonine, Phil Hugenholtzi, Nikos Kyrpidesi, Gerhard Wannerj, Paul Richardsoni, Martin Kellerc, and Karl O. Stettera,k,l aLehrstuhl fu¨r Mikrobiologie und Archaeenzentrum, Universita¨t Regensburg, D-93053 Regensburg, Germany; cBiosciences Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN 37831; dDepartment of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712; eNational Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20894; fDepartment of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520; gSchool of Life Sciences, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154; hLaboratoire de Chimie Bacte´rienne, Unite´ Propre de Recherche 9043, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Universite´de Provence Aix-Marseille I, 13331 Marseille Cedex 3, France; iU.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, Walnut Creek, CA 94598; jInstitute of Botany, Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich, D-80638 Munich, Germany; and kInstitute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095 Communicated by Carl R. Woese, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL, April 2, 2008 (received for review January 7, 2008) The candidate division Korarchaeota comprises a group of uncul- and sediment samples from Obsidian Pool as an inoculum. The tivated microorganisms that, by their small subunit rRNA phylog- cultivation system supported the stable growth of a mixed commu- eny, may have diverged early from the major archaeal phyla nity of hyperthermophilic bacteria and archaea including an or- Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota. -

Review Article Diversity of the DNA Replication System in the Archaea Domain

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Archaea Volume 2014, Article ID 675946, 15 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/675946 Review Article Diversity of the DNA Replication System in the Archaea Domain Felipe Sarmiento,1 Feng Long,1 Isaac Cann,2 and William B. Whitman1 1 Department of Microbiology, University of Georgia, 541 Biological Science Building, Athens, GA 30602-2605, USA 2 3408 Institute for Genomic Biology, University of Illinois, 1206 W Gregory Drive, Urbana, IL 61801, USA Correspondence should be addressed to William B. Whitman; [email protected] Received 21 October 2013; Accepted 16 February 2014; Published 26 March 2014 Academic Editor: Yoshizumi Ishino Copyright © 2014 Felipe Sarmiento et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The precise and timely duplication of the genome is essential for cellular life. It is achieved by DNA replication, a complex process that is conserved among the three domains of life. Even though the cellular structure of archaea closely resembles that of bacteria, the information processing machinery of archaea is evolutionarily more closely related to the eukaryotic system, especially for the proteins involved in the DNA replication process. While the general DNA replication mechanism is conserved among the different domains of life, modifications in functionality and in some of the specialized replication proteins are observed. Indeed, Archaea possess specific features unique to this domain. Moreover, even though the general pattern of the replicative system is the samein all archaea, a great deal of variation exists between specific groups. -

A Practical Introduction to Landmark-Based Geometric Morphometrics

A PRACTICAL INTRODUCTION TO LANDMARK-BASED GEOMETRIC MORPHOMETRICS MARK WEBSTER Department of the Geophysical Sciences, University of Chicago, 5734 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637 and H. DAVID SHEETS Department of Physics, Canisius College, 2001 Main Street, Buffalo, NY 14208 ABSTRACT.—Landmark-based geometric morphometrics is a powerful approach to quantifying biological shape, shape variation, and covariation of shape with other biotic or abiotic variables or factors. The resulting graphical representations of shape differences are visually appealing and intuitive. This paper serves as an introduction to common exploratory and confirmatory techniques in landmark-based geometric morphometrics. The issues most frequently faced by (paleo)biologists conducting studies of comparative morphology are covered. Acquisition of landmark and semilandmark data is discussed. There are several methods for superimposing landmark configu- rations, differing in how and in the degree to which among-configuration differences in location, scale, and size are removed. Partial Procrustes superimposition is the most widely used superimposition method and forms the basis for many subsequent operations in geometric morphometrics. Shape variation among superimposed con- figurations can be visualized as a scatter plot of landmark coordinates, as vectors of landmark displacement, as a thin-plate spline deformation grid, or through a principal components analysis of landmark coordinates or warp scores. The amount of difference in shape between two configurations can be quantified as the partial Procrustes distance; and shape variation within a sample can be quantified as the average partial Procrustes distance from the sample mean. Statistical testing of difference in mean shape between samples using warp scores as variables can be achieved through a standard Hotelling’s T2 test, MANOVA, or canonical variates analysis (CVA). -

Systematic Morphology of Fishes in the Early 21St Century

Copeia 103, No. 4, 2015, 858–873 When Tradition Meets Technology: Systematic Morphology of Fishes in the Early 21st Century Eric J. Hilton1, Nalani K. Schnell2, and Peter Konstantinidis1 Many of the primary groups of fishes currently recognized have been established through an iterative process of anatomical study and comparison of fishes that has spanned a time period approaching 500 years. In this paper we give a brief history of the systematic morphology of fishes, focusing on some of the individuals and their works from which we derive our own inspiration. We further discuss what is possible at this point in history in the anatomical study of fishes and speculate on the future of morphology used in the systematics of fishes. Beyond the collection of facts about the anatomy of fishes, morphology remains extremely relevant in the age of molecular data for at least three broad reasons: 1) new techniques for the preparation of specimens allow new data sources to be broadly compared; 2) past morphological analyses, as well as new ideas about interrelationships of fishes (based on both morphological and molecular data) provide rich sources of hypotheses to test with new morphological investigations; and 3) the use of morphological data is not limited to understanding phylogeny and evolution of fishes, but rather is of broad utility to understanding the general biology (including phenotypic adaptation, evolution, ecology, and conservation biology) of fishes. Although in some ways morphology struggles to compete with the lure of molecular data for systematic research, we see the anatomical study of fishes entering into a new and exciting phase of its history because of recent technological and methodological innovations. -

Comparative Anatomy and Functional Morphology University of California at Berkeley Department of Integrative Biology (5 Units)

Comparative Anatomy and Functional Morphology University of California at Berkeley Department of Integrative Biology (5 Units) Course Description: This course is an in-depth look at the biology of form and function. We will examine vertebrate anatomy to understand how structures develop, how they have evolved, and how they interact with one another to allow animals to live in a variety of environments. We will study the integration of the skeletal, muscular, nervous, vascular, respiratory, digestive, endocrine, and urogenital systems to explore the historical and present diversity of vertebrate animals. Format: This course will include lecture, discussion, and laboratory sessions. Lectures will focus primarily on broad concepts and ideas. Discussion sections will emphasize how to both read and analyze primary scientific literature. Laboratory sessions will allow students to physically explore the morphologies of a diversity of taxa and will include museum specimens as well as dissections of whole animals. Lecture: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, 9:30-11:00a.m. Discussion: Monday and Thursday, 11:00a.m. or 12:00p.m. Laboratory: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, 2:00-5:00p.m. All students must take lectures, discussion sections, and laboratory sections concurrently. Attendance of all sections is required. Goals: 1. A comparative approach will allow students to gain experience in identifying similarities and differences among taxa and further their understanding of how both evolutionary and environmental contexts influence the morphology and function. 2. Students will improve their ability to ask questions and answer them using scientific methodology. 3. Students will gain factual knowledge of terms and concepts regarding vertebrate anatomy and functional morphology. -

Biogenesis and Functions of Bacterial S-Layers

REVIEWS Biogenesis and functions of bacterial S‑layers Robert P. Fagan1 and Neil F. Fairweather2 Abstract | The outer surface of many archaea and bacteria is coated with a proteinaceous surface layer (known as an S-layer), which is formed by the self-assembly of monomeric proteins into a regularly spaced, two-dimensional array. Bacteria possess dedicated pathways for the secretion and anchoring of the S-layer to the cell wall, and some Gram-positive species have large S-layer-associated gene families. S-layers have important roles in growth and survival, and their many functions include the maintenance of cell integrity, enzyme display and, in pathogens and commensals, interaction with the host and its immune system. In this Review, we discuss our current knowledge of S-layer and related proteins, including their structures, mechanisms of secretion and anchoring and their diverse functions. S‑layers are found on both Gram-positive and Gram- 1980s. Recent advances in genomics and structural biol‑ negative bacteria and are highly prevalent in archaea1–3. ogy, together with the development of new molecular They are defined as two-dimensional (2D) crystalline cloning tools for many species, have facilitated struc‑ arrays that coat the entire cell, and they are thought tural and functional studies of SLPs. Comprehensive to provide important functional properties. S‑layers reviews about S‑layers were written over a decade consist of one or more (glyco)proteins, known as S‑layer ago1,2, and others have emphasized the exploitation of proteins (SLPs), that undergo self-assembly to form a SLPs in nanotechnology1,2,5,6. -

Bacterial Size, Shape and Arrangement & Cell Structure And

Lecture 13, 14 and 15: bacterial size, shape and arrangement & Cell structure and components of bacteria and Functional anatomy and reproduction in bacteria Bacterial size, shape and arrangement Bacteria are prokaryotic, unicellular microorganisms, which lack chlorophyll pigments. The cell structure is simpler than that of other organisms as there is no nucleus or membrane bound organelles.Due to the presence of a rigid cell wall, bacteria maintain a definite shape, though they vary as shape, size and structure. When viewed under light microscope, most bacteria appear in variations of three major shapes: the rod (bacillus), the sphere (coccus) and the spiral type (vibrio). In fact, structure of bacteria has two aspects, arrangement and shape. So far as the arrangement is concerned, it may Paired (diplo), Grape-like clusters (staphylo) or Chains (strepto). In shape they may principally be Rods (bacilli), Spheres (cocci), and Spirals (spirillum). Size of Bacterial Cell The average diameter of spherical bacteria is 0.5- 2.0 µm. For rod-shaped or filamentous bacteria, length is 1-10 µm and diameter is 0.25-1 .0 µm. E. coli , a bacillus of about average size is 1.1 to 1.5 µm wide by 2.0 to 6.0 µm long. Spirochaetes occasionally reach 500 µm in length and the cyanobacterium Accepted wisdom is that bacteria are smaller than eukaryotes. But certain cyanobacteria are quite large; Oscillatoria cells are 7 micrometers diameter. The bacterium, Epulosiscium fishelsoni , can be seen with the naked eye (600 mm long by 80 mm in diameter). One group of bacteria, called the Mycoplasmas, have individuals with size much smaller than these dimensions. -

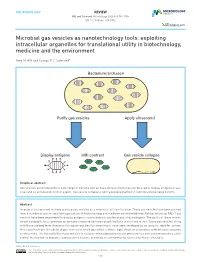

Microbial Gas Vesicles As Nanotechnology Tools: Exploiting Intracellular Organelles for Translational Utility in Biotechnology, Medicine and the Environment

REVIEW Hill and Salmond, Microbiology 2020;166:501–509 DOI 10.1099/mic.0.000912 Microbial gas vesicles as nanotechnology tools: exploiting intracellular organelles for translational utility in biotechnology, medicine and the environment Amy M. Hill and George P. C. Salmond* Bacterium/archaeon Purify gas vesicles Apply ultrasound Display antigens MRI contrast Gas vesicle collapse Graphical abstract Gas vesicles are produced by a wide range of bacteria and archaea. Once purified they can be used to display antigens in vac- cines and as ultrasound contrast agents. Gas vesicle collapse is also a possible method to control cyanobacterial blooms. Abstract A range of bacteria and archaea produce gas vesicles as a means to facilitate flotation. These gas vesicles have been purified from a number of species and their applications in biotechnology and medicine are reviewed here. Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 gas vesicles have been engineered to display antigens from eukaryotic, bacterial and viral pathogens. The ability of these recom- binant nanoparticles to generate an immune response has been quantified both in vitro and in vivo. These gas vesicles, along with those purified from Anabaena flos- aquae and Bacillus megaterium, have been developed as an acoustic reporter system. This system utilizes the ability of gas vesicles to retain gas within a stable, rigid structure to produce contrast upon exposure to ultrasound. The susceptibility of gas vesicles to collapse when exposed to excess pressure has also been proposed as a bio- control mechanism to disperse cyanobacterial blooms, providing an environmental function for these structures. 000912 © 2020 The Authors This is an open- access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License. -

Direct Observation of Protein Secondary Structure in Gas Vesicles by Atomic Force Microscopy

2432 Biophysical Journal Volume 70 May 1996 2432-2436 Direct Observation of Protein Secondary Structure in Gas Vesicles by Atomic Force Microscopy T. J. McMaster,* M. J. Miles,* and A. E. Walsbyt *H. H. Wills Physics Laboratory, and *Department of Botany, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TL England ABSTRACT The protein that forms the gas vesicle in the cyanobacterium Anabaena flos-aquae has been imaged by atomic force microscopy (AFM) under liquid at room temperature. The protein constitutes "ribs" which, stacked together, form the hollow cylindrical tube and conical end caps of the gas vesicle. By operating the microscope in deflection mode, it has been possible to achieve sub-nanometer resolution of the rib structure. The lateral spacing of the ribs was found to be 4.6 ± 0.1 nm. At higher resolution the ribs are observed to consist of pairs of lines at an angle of -55° to the rib axis, with a repeat distance between each line of 0.57 ± 0.05 nm along the rib axis. These observed dimensions and periodicities are consistent with those determined from previous x-ray diffraction studies, indicating that the protein is arranged in ,B-chains crossing the rib at an angle of 550 to the rib axis. The AFM results confirm the x-ray data and represent the first direct images of a ,3-sheet protein secondary structure using this technique. The orientation of the GvpA protein component of the structure and the extent of this protein across the ribs have been established for the first time. INTRODUCTION Gas vesicle protein and structure Gas vesicles are hollow structures that provide buoyancy in volume of this unit cell, 10.25 nm3, corresponds with that of various aquatic microorganisms.