The Philosophy of Chemistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Companion to Analytic Philosophy

A Companion to Analytic Philosophy Blackwell Companions to Philosophy This outstanding student reference series offers a comprehensive and authoritative survey of philosophy as a whole. Written by today’s leading philosophers, each volume provides lucid and engaging coverage of the key figures, terms, topics, and problems of the field. Taken together, the volumes provide the ideal basis for course use, represent- ing an unparalleled work of reference for students and specialists alike. Already published in the series 15. A Companion to Bioethics Edited by Helga Kuhse and Peter Singer 1. The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy Edited by Nicholas Bunnin and Eric 16. A Companion to the Philosophers Tsui-James Edited by Robert L. Arrington 2. A Companion to Ethics Edited by Peter Singer 17. A Companion to Business Ethics Edited by Robert E. Frederick 3. A Companion to Aesthetics Edited by David Cooper 18. A Companion to the Philosophy of 4. A Companion to Epistemology Science Edited by Jonathan Dancy and Ernest Sosa Edited by W. H. Newton-Smith 5. A Companion to Contemporary Political 19. A Companion to Environmental Philosophy Philosophy Edited by Robert E. Goodin and Philip Pettit Edited by Dale Jamieson 6. A Companion to Philosophy of Mind 20. A Companion to Analytic Philosophy Edited by Samuel Guttenplan Edited by A. P. Martinich and David Sosa 7. A Companion to Metaphysics Edited by Jaegwon Kim and Ernest Sosa Forthcoming 8. A Companion to Philosophy of Law and A Companion to Genethics Legal Theory Edited by John Harris and Justine Burley Edited by Dennis Patterson 9. A Companion to Philosophy of Religion A Companion to African-American Edited by Philip L. -

Philosophical Theory-Construction and the Self-Image of Philosophy

Open Journal of Philosophy, 2014, 4, 231-243 Published Online August 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojpp http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2014.43031 Philosophical Theory-Construction and the Self-Image of Philosophy Niels Skovgaard Olsen Department of Philosophy, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany Email: [email protected] Received 25 May 2014; revised 28 June 2014; accepted 10 July 2014 Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract This article takes its point of departure in a criticism of the views on meta-philosophy of P.M.S. Hacker for being too dismissive of the possibility of philosophical theory-construction. But its real aim is to put forward an explanatory hypothesis for the lack of a body of established truths and universal research programs in philosophy along with the outline of a positive account of what philosophical theories are and of how to assess them. A corollary of the present account is that it allows us to account for the objective dimension of philosophical discourse without taking re- course to the problematic idea of there being worldly facts that function as truth-makers for phi- losophical claims. Keywords Meta-Philosophy, Hacker, Williamson, Philosophical Theories 1. Introduction The aim of this article is to use a critical discussion of the self-image of philosophy presented by P. M. S. Hacker as a platform for presenting an alternative, which offers an account of how to think about the purpose and cha- racter of philosophical theories. -

God As Both Ideal and Real Being in the Aristotelian Metaphysics

God As Both Ideal and Real Being In the Aristotelian Metaphysics Martin J. Henn St. Mary College Aristotle asserts in Metaphysics r, 1003a21ff. that "there exists a science which theorizes on Being insofar as Being, and on those attributes which belong to it in virtue of its own nature."' In order that we may discover the nature of Being Aristotle tells us that we must first recognize that the term "Being" is spoken in many ways, but always in relation to a certain unitary nature, and not homonymously (cf. Met. r, 1003a33-4). Beings share the same name "eovta," yet they are not homonyms, for their Being is one and the same, not manifold and diverse. Nor are beings synonyms, for synonymy is sameness of name among things belonging to the same genus (as, say, a man and an ox are both called "animal"), and Being is no genus. Furthermore, synonyms are things sharing a common intrinsic nature. But things are called "beings" precisely because they share a common relation to some one extrinsic nature. Thus, beings are neither homonyms nor synonyms, yet their core essence, i.e. their Being as such, is one and the same. Thus, the unitary Being of beings must rest in some unifying nature extrinsic to their respective specific essences. Aristotle's dialectical investigations into Being eventually lead us to this extrinsic nature in Book A, i.e. to God, the primary Essence beyond all specific essences. In the pre-lambda books of the Metaphysics, however, this extrinsic nature remains very much up for grabs. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Historical Tension Between the Holistic and Dualistic View of Man in the Church

Page 1 of 8 Original Research Historical tension between the holistic and dualistic view of man in the church Author: Dualism has continually plagued the Church, especially from the time when Greek philosophers 1 Herm Zandman articulated the dualistic view of man in an excellent, scholarly way. Even when the Reformers Affiliations: militated against this phenomenon theologically, it still dominated life in general and 1Theological Faculty Christian living in particular. This article considered the historical tension between the holistic North-West University, and dualistic view of man in the church. It strove to do this by setting forth certain examples Potchefstroom Campus, from history, showing how the Church wrestled with this tension. Furthermore, the author South Africa attempted to point out in which way the dualistic view of man was damaging to godly living, Correspondence to: and why a holistic view of man was conducive to life under God in an ethically meaningful Herm Zandman manner. Email: [email protected] Die historiese spanning tussen die holistiese en dualistiese beeld van die mens in die Postal Address: kerk. Dualisme het die Kerk nog altyd beinvloed, veral sedert die era toe Griekse filosowe die 25 Hay Terrace, Kongorong dualistiese siening van die mens op ‘n uitstekende akademiese wyse bekendgestel het. Selfs 5291, South Australia toe die Reformeerders teologies te velde getrek het teen hierdie fenomeen, het dit die lewe in Dates: die algemeen en die Christelike lewe in die besonder aangetas. Hierdie artikel oorweeg die Received: 28 Feb. 2011 historiese spanning tussen die holistiese en dualistiese sienings in die kerk. Sekere voorbeelde Accepted: 25 July 2011 uit die geskiedenis sal voorgehou word ter illustrasie van hoe die Kerk met hierdie spanning Published: 02 Oct. -

THE EPISTEMOLOGICAL AUTONOMY of CHEMISTRY By

THE EPISTEMOLOGICAL AUTONOMY OF CHEMISTRY By ROBIN PFLUGHAUPT Integrated Studies Project submitted to Dr. Russell Thompson in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta November, 2009 THE EPISTEMOLOGICAL AUTONOMY OF CHEMISTRY 2 Abstract The “logicians’ program” or attempt to situate scientific methodology within a logical framework has come to a standstill following radical developments within the philosophy of science and science and technology studies. One of the most persistent concepts remaining from the traditional philosophy of science or logical empiricism however is the unification of science through the reducibility of chemical and biological phenomena to physical laws and explanations. Towards the end of the 19th century, chemistry underwent a physical revolution in order to describe dynamic processes and express chemical phenomena mathematically, and developments within quantum mechanics during the 1920s encouraged the assumption that chemistry is fully reducible to physics. Theoretical chemistry is briefly overviewed to reveal that quantum chemistry developed through the assistance of models developed within the “organic structuralist tradition” and empirical data to generate abstract approximations that are cumbersome to calculate. From these approximations, however chemists have produced powerful models, in particular molecular orbitals, that have become invaluable conceptual tools within chemistry since they “black box” quantum mechanical calculations and rationalize chemical processes. Despite shared ontology between physics and chemistry, since it is impossibly cumbersome to fully explain chemical phenomena at the particle level, there is the appearance of “emergentism” at the molecular level, and physics does not capture chemistry’s engineering ideology and “disciplinary matrices”, philosophical concepts including “supervenience” have been used to argue for the epistemological autonomy of chemistry. -

Kant's Critique of Judgment and the Scientific Investigation of Matter

Kant’s Critique of Judgment and the Scientific Investigation of Matter Daniel Rothbart, Irmgard Scherer Abstract: Kant’s theory of judgment establishes the conceptual framework for understanding the subtle relationships between the experimental scientist, the modern instrument, and nature’s atomic particles. The principle of purposive- ness which governs judgment has also a role in implicitly guiding modern experimental science. In Part 1 we explore Kant’s philosophy of science as he shows how knowledge of material nature and unobservable entities is possible. In Part 2 we examine the way in which Kant’s treatment of judgment, with its operating principle of purposiveness, enters into his critical project and under- lies the possibility of rational science. In Part 3 we show that the centrality given to judgment in Kant’s conception of science provides philosophical in- sight into the investigation of atomic substances in modern chemistry. Keywords : Kant , judgment , purposiveness , experimentation , investigation of matter . Introduction Kant’s philosophy of science centers on the problem of how it is possible to acquire genuine knowledge of unobservable entities, such as atoms and molecules. “What and how much can the understanding and reason know apart from all experience?” ( CPuR , Axvii). This raises the question of the role of experiments in the knowability ( Erkennbarkeit ) and the experientiality (Erfahrbarkeit ) of nature. Kant’s insights into the character of scientific experimentation are not given the hearing they deserve. We argue that Kant’s theory of judgment establishes the conceptual framework for understanding the subtle inter- actions between the experimental chemist, the modern chemical instrument, and molecular substance. -

The Origins and Legacy of Quine's Naturalism

The Origins and Legacy of Quine’s Naturalism 17-18 December 2019 ABSTRACTS Jansenn-Lauret and Macbride: W.V. Quine and David Lewis: Structural (Epistemological) Humility. In this paper we argue that W.V. Quine and D.K. Lewis, despite their differences and their different receptions, came to a common intellectual destination: epistemological structuralism. We begin by providing an account of Quine’s epistemological structuralism as it came to its mature development in his final works, Pursuit of Truth (1990) and From Stimulus to Science (1995), and we show how this doctrine developed our of his earlier views on explication and the inscrutability of reference. We then turn to the correspondence between Quine and Lewis which sets the scene for Lewis’s adoption of structuralism vis-a-vis set theory in the Appendix to his Parts of Classes (1990). We conclude, drawing further from Lewis’s correspondence, by arguing that Lewis proceeded from there to embrace in one of his own final papers, ‘Ramseyan Humility’ (2001), an encompassing form of epistemological structuralism, whilst discharging the doctrine of reference magnetism that had hitherto set Lewis apart from Quine. Rogério Severo: A change in Quine’s reasons for holophrastic indeterminacy of translation Up until the early 1970s Quine argued that the underdetermination of theories by observations is a reason for holophrastic indeterminacy of translation. This is still today thought of as Quine’s main reason for the thesis. Yet, his 1975 formulation of underdetermination renders that argument invalid. This paper explains why. It also indicates Quine’s reasons for holophrastic indeterminacy after 1975, and offers an additional reason for it. -

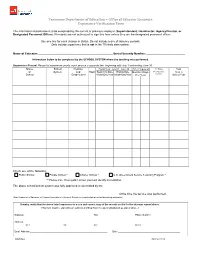

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

1 What to Take Away from Sellars's Kantian Naturalism James R. O

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PhilPapers What to Take Away from Sellars’s Kantian Naturalism James R. O’Shea, University College Dublin (This is the author’s post-peer reviewed version. For citations, please refer to the published version in: James R. O’Shea, ed., Sellars and His Legacy, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. 130–148.) ABSTRACT: I contend that Sellars defends a uniquely Kantian naturalist outlook both in general and more particularly in relation to the nature and status of what he calls ‘epistemic principles’; and I attempt to show that this remains a plausible and distinctive position even when detached from Sellars’s quasi-Kantian transcendental idealist contention that the perceptible objects of the manifest image strictly speaking do not exist, i.e., as conceived within that common sense framework. I first explain the complex Kant-inspired sense in which Sellars did not take the latter thesis concerning the objects of the manifest image to apply, at least in certain fundamental respects, to persons. In this primary Kantian sense, I suggest, persons as thinkers and agents exist univocally across both the manifest and scientific images, and this in principle would enable an integration of persons within a multi-leveled naturalistic ontology, one that is independent of Sellars’s quasi-Kantian transcendental idealist thesis. Finally, I examine in some detail how this defensible blend of Kantian and naturalist themes turns out to be what is fundamental in Sellars’s complex and controversial views on the nature and status of epistemic principles. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it.