Fiscal Gap and Financing Protected Areas in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A5 8Pp Format

Palawan ‘CAN ’ Palawan is 1,780 islands of pristine white beaches, dramatic rock A nature lover ’s paradise and an formations, secret coves and underground mysteries. An untamed CULTURE . The island province of Palawan land, a nature lover’s paradise and an adventurer’s dream: Palawan adventurer ’s dream has much to offer to those who want to get to certainly lives up to its image as the last frontier. LAOAG the heart and soul of the Philippines. The more Getting there adventurous traveller can visit one of Palawan’s The island province has been declared a nature sanctuary of the world Palawan Banaue Major Airport Gateways: indigenous people, the Batak, whose settlements and for good reason. It is wrapped in a mantel of rainforests, outstanding Luzon dive sites, majestic mountains, primeval caves and shimmering beaches. Puerto Princesa, El Nido, Sandoval, Busuanga and PHILIPPINE SEA are on the slope of Cleopatra’s Needle. The Tabon Cuyo. Distance from Manila to Puerto Princesa is and Palawan Museums with their displays of It bursts with exotic flora and fauna and is surrounded by a coral shelf 306 nautical miles MANILAMMAMANMANIMANIL prehistoric artifacts from the Tabon caves and that abounds with varied and colourful marine life. Air Transport: items from the Spanish era bring the areas’ local Mindoro The long narrow strip of the main island, located southwest of Manila, Various domestic carriers fly to Palawan's major history to life and are well worth exploring. gateways from Manila (20+ flights daily), Cebu Busuanga Boracay Samar is around 425 kilometres long and 40 kilometres at its widest. -

QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT 8 October-December 2018

5 PROTECT WILDLIFE QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT 8 October-December 2018 JANUARY 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI Global, LLC PROTECT WILDLIFE ACTIVITY WORK PLAN FOR YEAR 1 1 Activity Title: Protect Wildlife Activity Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Philippines Contract Number: AID-OAA-I-14-00014/AID-492-TO-16-00002 Contractor: DAI Global, LLC Date of Publication: January 2019 Author: DAI Global, LLC The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 2 PROTECT WILDLIFE QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT 8 CONTENTS PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................... iii ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 1 MONITORING, EVALUATION AND LEARNING .......................................................... 3 2 PROGRESS REPORT ......................................................................................................... 19 3 MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION ................................................................... 49 4 PAST AND PROJECTED EXPENDITURES .................................................................. -

Rattanewsletter No. 2

The Official News Bulletin of the ITTO PD 334/05 Rev. 2 (I) No. 2 Vol. 1 June 2007 ISSN 1908-5974 ITTO– Philippines—ASEAN Rattan Project First Project Steering Committee Held The 1st Project Steering Committee ( PSC ) Meeting for the ITTO-Philippines-ASEAN Rattan Project was held on 21 February 2007 at the Ecosystems Research and Development Bureau ( ERDB ) Conference Room, College, Laguna, Philippines. It was chaired by the Pro- ject Director and Director of the ERDB Forester Marcial C. Amaro, Jr. The committee members in attendance were: For. Eriberto C. Argete ( Department of Environment and Natural Re- sources ) , Dr. Lauren Flejzor ( ITTO Representative ) , For. Ester Cadiz ( represented For. Romeo Acosta of the Forest Management Bureau ) , Dr. Florence P. Soriano ( Forest Prod- ucts Research and Development Institute) and Dean Ramon A. Razal ( College of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of the Philippines at Los Baños ) . The Project Management Team composed of Dr. Aida B. Lapis ( Deputy Project Director and Leader Research Compo- nent ) , Dr. Merlyn Carmelita N. Rivera ( Project Leader, Production Aspect and Leader, Net- working Component ) , Dr. Magdalena Giron ( Project Leader, Utilization Aspect and Leader, Training Component) , Dr. Armando M. Palijon ( Leader, Pilot Demonstration Component ) and For. Imelda C. Pangga ( Database Administrator ) participated during the meet- ing together with Dr. Florentino O. Tesoro, Technical Consultant on Utilization. The other members of the project team namely: Ms. Norma Pablo, For. Kharina G. Bueser, For. Gregorio E. Santos, Jr., and For. Moreno L. Santander ( Philippine Contact Person ) also attended the meeting. The Project ’ s objectives, outputs and detailed work and financial plans, organiza- IN THIS ISSUE tional chart and progress report were presented by Dr. -

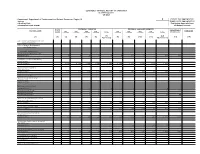

Current Year Appropriation Agency: Supplemental Appropriations Operating Unit: Continuing Appropriations Organization Code (UACS) Off-Budget Account

QUARTERLY PHYSICAL REPORT OF OPERATION As of 4TH Quarter CY 2017 Department: Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Region IX X Current Year Appropriation Agency: Supplemental Appropriations Operating Unit: Continuing Appropriations Organization Code (UACS) Off-Budget Account PHYSICAL TARGETS PHYSICAL ACCOMPLISHMENT UACS VARIANCE AS OF PARTICULARS 1ST 2ND 3RD 4TH 1ST 2ND 3RD 4TH REMARKS CODE TOTAL TOTAL December 2017 QUARTER QUARTER QUARTER QUARTER QUARTER QUARTER QUARTER QUARTER (7) (12) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (8) (9) (10) (11) (13) (14) =(3+4+5+6) =(8+9+10+11) A.01 General Administration and Support Services A.01.a General Management and Supervision 1. Personnel Management Appointment preparation (no) Regional Office 2 3 1 2 8 2 137 3 142 134 Personnel records maintained/ updated (no) Regional Office 1,700 1,700 1,700 1,700 1,700 1,700 1,700 1,700 1,700 1,700 Applications/clearance processed (no) Regional Office 150 150 150 150 600 160 140 300 60 660 60 2. Procurement Services Agency procurement plan prepared (no) Regional Office 1 1 1 1 Bidding conducted (no) Regional Office 1 1 1 1 4 2 2 2 6 2 Zamboanga del Norte 1 1 1 1 4 1 7 4 5 17 13 Zamboanga Del Sur 1 1 1 1 4 2 2 4 Zamboanga Sibugay 1 1 1 1 4 2 20 8 30 26 Abstract of quotation/purchase order approved (no) Regional Office 10 15 15 20 60 360 40 204 604 544 Resolutions approved (no) Regional Office 5 5 10 40 60 113 179 249 63 604 544 Documents on procurement for payment Regional Office 10 20 30 60 120 166 218 243 495 1,122 1,002 Agency purchase request acquired (PS-DBM) (no) Regional Office 1 1 1 3 7 6 9 (10) 12 9 Purchased request acted upon(no) Regional Office 15 30 30 40 115 275 255 365 314 1,209 1,094 3. -

DIRECTORY of PDIC MEMBER RURAL BANKS As of 27 July 2021

DIRECTORY OF PDIC MEMBER RURAL BANKS As of 27 July 2021 NAME OF BANK BANK ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBER * 1 Advance Credit Bank (A Rural Bank) Corp. (Formerly Advantage Bank Corp. - A MFO RB) Stop Over Commercial Center, Gerona-Pura Rd. cor. MacArthur Highway, Brgy. Abagon, Gerona, Tarlac (045) 931-3751 2 Agribusiness Rural Bank, Inc. 2/F Ropali Plaza Bldg., Escriva Dr. cor. Gold Loop, Ortigas Center, Brgy. San Antonio, City of Pasig (02) 8942-2474 3 Agricultural Bank of the Philippines, Inc. 121 Don P. Campos Ave., Brgy. Zone IV (Pob.), City of Dasmariñas, Cavite (046) 416-3988 4 Aliaga Farmers Rural Bank, Inc. Gen. Luna St., Brgy. Poblacion West III, Aliaga, Nueva Ecija (044) 958-5020 / (044) 958-5021 5 Anilao Bank (Rural Bank of Anilao (Iloilo), Inc. T. Magbanua St., Brgy. Primitivo Ledesma Ward (Pob.), Pototan, Iloilo (033) 321-0159 / (033) 362-0444 / (033) 393-2240 6 ARDCIBank, Inc. - A Rural Bank G/F ARDCI Corporate Bldg., Brgy. San Roque (Pob.), Virac, Catanduanes (0908) 820-1790 7 Asenso Rural Bank of Bautista, Inc. National Rd., Brgy. Poblacion East, Bautista, Pangasinan (0917) 817-1822 8 Aspac Rural Bank, Inc. ASPAC Bank Bldg., M.C. Briones St. (Central Nautical Highway) cor. Gen. Ricarte St., Brgy. Guizo, City of Mandaue, Cebu (032) 345-0930 9 Aurora Bank (A Microfinance-Oriented Rural Bank), Inc. GMA Farms Building, Rizal St., Brgy. V (Pob.), Baler, Aurora (042) 724-0095 10 Baclaran Rural Bank, Inc. 83 Redemptorist Rd., Brgy. Baclaran, City of Parañaque (02) 8854-9551 11 Balanga Rural Bank, Inc. Don Manuel Banzon Ave., Brgy. -

STATE of the COASTS of Guimaras Province

STATE OF THE COASTS of Guimaras Province The Provincial Government of Guimaras, Philippines GEF UNOPS Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA) State of the Coasts of Guimaras Province The Provincial Government of Guimaras, Philippines GEF UNOPS Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA) State of the Coasts of Guimaras Province April 2012 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes or to provide wider dissemination for public response, provided prior written permission is obtained from the PEMSEA Resource Facility Executive Director, acknowledgment of the source is made and no commercial usage or sale of the material occurs. PEMSEA would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any purpose other than those given above without a written agreement between PEMSEA and the requesting party. Published by the Provincial Government of Guimaras, Philippines, and Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA). 135 p. Printed in Quezon City, Philippines Provincial Government of Guimaras, Philippines and PEMSEA. 2012. State of the Coasts of Guimaras Province. Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA), Quezon City, Philippines. ISBN XXX-XXX-XXX-XXX-X PEMSEA is a GEF Project Implemented by UNDP and Executed by UNOPS. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS), and the other participating organizations. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

List of Figures Figure 1 Priority Protected Areas for Ecotourism Within Key Biodiversity Areas and Tourism Development Areas

List of Figures Figure 1 Priority protected areas for ecotourism within Key Biodiversity Areas and Tourism Development Areas Figure 2 Total number of visitors to protected areas and total income generated from 2014 to 2017 List of Tables Table 1 Priority protected areas for ecotourism development within KBAs List of Footnotes 1 NTDP 2016-2022 Tourism Development Clusters and Areas Source: DENR-Biodiversity Management Bureau, 2018 Figure 1. Priority protected areas for ecotourism within Key Biodiversity Areas and Tourism Development Areas 2,000,000 80,000,000.00 1,800,000 70,000,000.00 1,600,000 60,000,000.00 1,400,000 Income 1,200,000 50,000,000.00 1,000,000 40,000,000.00 800,000 30,000,000.00 600,000 Number of visitors of Number 20,000,000.00 400,000 200,000 10,000,000.00 - 0.00 2014 2015 2016 2017 Local Male Local Female Foreign Male Foreign Female Total Income Source: DENR-Biodiversity Management Bureau, 2018 Figure 2. Total number of visitors to protected areas and total income generated from 2014 to 2017. Table 1. Priority protected areas for ecotourism development within KBAs REGION PROTECTED AREA Ecotourism Products/ Activities 1. CAR Mount Pulag National Park Mountain climbing, camping, cultural visit, photography, cloud formation watching 2. CAR Balbalasang Balbalan National Park Hiking, camping 3. Region 1 Kalbario Patapat Natural Park Hiking, caving, biking, diving, camping 4. Region 1 Manleluag Spring Protected Landscape Trekking, hot spring swimming 5. Region 1 Hundred Island National Park Boating, island hopping, 6. Region 2 Batanes Protected Landscape and Village tour, hiking, photography, biking, Seascape caving 7. -

February 20142014

TAO-Pilipinasyoungprofessionalsprogram e-newslettere-newsletter JJANUARYANUARY -- FEBRUARYFEBRUARY 20142014 ” . s u School children from Decalachao Elementary o In this issue: t School in Coron, Palawan attend the morning e flag ceremony and continue to hold classes in m o classroom buildings severely damaged by typhoon c Shelter Planning Workshop o Yolanda. (Photo by Verna Sarraga) t , r for NaSaMa * Christmas Gift- o o p e giving for Children * Technical h t www.ypws.tao-pilipinas.org y l Assistance for SHFC’s HDH l a i c e Project in Bacoor * p TAO and FDUP Conduct Shelter s e YP Lectures at Mapua , e l Planning Workshop for NaSaMa p o ARIDBE and UST-CA * e p Angat Calamianes Project e h t N ECEMBER THE OUNDATION FOR THE EVELOPMENT OF THE RBAN OOR k O D 9, 2013, F D U P s a (FDUP) together with TAO-Pilipinas, Inc. conducted a planning workshop n Network Activities: a for Barangay 177, Caloocan City particularly for the communities under h t r Nagkakaisang Samahan ng mga Maralita sa Barangay 177 (NaSaMa). The Yolanda Conversations e h workshop was intended to 1) introduce the Community Architect’s Network t PMPI NCC Meeting a r (CAN) and the City Wide Development Approach (CDA) to the communities e l under NaSaMa; and 2) come up with an action plan for the community wide p o upgrading of Barangay 177. e p YP Reading List: e h t Loft’s Practical Ideas for Pls. turn to page 2. o g Small Spaces o t Cocoro Book’s Small House s u Mapua ARIDBE Hosts First YP r Tokyo o f e m i Lecture for 2014 t s ’ t I “ MAPUA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY THROUGH ITS SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, INDUSTRIAL Design, and the Built Environment (MIT-ARIDBE) hosted the first Young Professionals (YP) Lecture for 2014 held on January 8. -

DENR-BMB Atlas of Luzon Wetlands 17Sept14.Indd

Philippine Copyright © 2014 Biodiversity Management Bureau Department of Environment and Natural Resources This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the Copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. BMB - DENR Ninoy Aquino Parks and Wildlife Center Compound Quezon Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Philippines 1101 Telefax (+632) 925-8950 [email protected] http://www.bmb.gov.ph ISBN 978-621-95016-2-0 Printed and bound in the Philippines First Printing: September 2014 Project Heads : Marlynn M. Mendoza and Joy M. Navarro GIS Mapping : Rej Winlove M. Bungabong Project Assistant : Patricia May Labitoria Design and Layout : Jerome Bonto Project Support : Ramsar Regional Center-East Asia Inland wetlands boundaries and their geographic locations are subject to actual ground verification and survey/ delineation. Administrative/political boundaries are approximate. If there are other wetland areas you know and are not reflected in this Atlas, please feel free to contact us. Recommended citation: Biodiversity Management Bureau-Department of Environment and Natural Resources. 2014. Atlas of Inland Wetlands in Mainland Luzon, Philippines. Quezon City. Published by: Biodiversity Management Bureau - Department of Environment and Natural Resources Candaba Swamp, Candaba, Pampanga Guiaya Argean Rej Winlove M. Bungabong M. Winlove Rej Dumacaa River, Tayabas, Quezon Jerome P. Bonto P. Jerome Laguna Lake, Laguna Zoisane Geam G. Lumbres G. Geam Zoisane -

2018 Annual Budget Report

Provincial Government of Palawan LOCALLY FUNDED PROGRAMS/ACTIVITIES/PROJECTS (Aligned with PDP 2017-2022, Ambisyon 2040, Agenda 2030 and Sendai Framework) Budget Year 2018 PARTICULARS FY 2018 1.0 MALASAKIT 1.1 Ensuring People Centered , Clean, Efficient and Effective Governance Gobyerno sa Barangay (GSB) 150,000,000.00 Inter - LGU Alliance Program 950,000.00 Expanded Project Evaluation & Monitoring 1,425,000.00 MIMAROPA Project Devt Assistance Center 1,425,000.00 Provincial Statistical System Development Program 2,789,907.00 Human Resource Training and Development Program 1,425,000.00 Enhancement of Jail Management 5,000,000.00 Capitol Complex Maintenance & Security Program 29,685,780.00 Legislative Research and Extension Services 9,025,000.00 Contribution to Vice Governor's League 95,000.00 Legislation Enhancement Program 15,295,000.00 Sangguniang Panlalawigan Committee Meetings 665,000.00 Publication of Ordinances 950,000.00 Aid to Palawan Councilor's League 95,000.00 Aid to Liga ng mga Barangay 45,000.00 Aid to Provincial Board Member's League 200,000.00 Aid to Vice Mayor's League 50,000.00 Enhancement of of SP Secretariat 237,500.00 Legislative Tracking Services 95,000.00 8888 Citizens Complaint Center 898,415.00 Development Information Management Program 8,000,000.00 Support to Conditional Matching Grant to Provinces (CMGP) 2,500,000.00 E - Governance / I - Tax Program 7,600,000.00 Information Technology Development Program 1,500,000.00 Public Financial Management System 2,850,000.00 PARTICULARS FY 2018 Internal Audit Program 950,000.00 Procurement System Enhancement Program 700,000.00 Repair & Renovation of Government Facilties 2,403,500.00 Real Property Management Program (Provincial Auction Committee) 500,000.00 General Revision of Real Property Assessment 6,650,000.00 PTO - Coron Extension Office - Inter-Agency Grants and Aids: Aid to Tubbataha Protection Mgnt. -

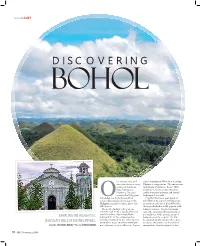

DISCOVERING Bohol

wanderLUST DISCOVERING Bohol ver the past 10 years I a week lounging on White Beach, asking have visited almost every Filipinos for suggestions. The answer was country in Southeast surprisingly unanimous: Bohol. With Asia, from Laos to promises of dreamy tropical beaches, Indonesia. But until cuddly miniature primates and surreal recently the Philippines landscapes, I was sold. had eluded me. To be honest, I had Frankly, I had never even heard of Onever really considered traveling to the Bohol before my trip to the Philippines. Philippines, mainly because I knew very Located a stone’s throw from Cebu City, little about it. the tropical island is wildly popular with Then, after fi nding a cheap promo domestic tourists. Despite remaining ticket through AirAsia, I suddenly found under the international tourist radar, it myself boarding a last-minute fl ight is actually one of the most frequented SAMPLING THE DELIGHTFUL to Cebu City. As the archipelago was destinations in the country. The few uncharted territory for me, I was clueless foreign visitors who venture there do so CHOCOLATE HILLS OF THE PHILIPPINES. about where to go, other than visiting the to explore the pristine coral reefs that WORDS JUSTINE LOPEZ | PHOTOS TONY KUEHN world-famous beaches of Boracay. I spent surround the island and give Bohol its 10 JPLUS November 23, 2014 wanderLUST reputation as one of the top 10 dive spots in place is so great, why had I never heard of it the world. before? And why don’t more people visit it? Because I’m not a diver, I came to check `I booked a hotel room in the quaint were surprisingly few tourists.