Monday Morning in Mernda Peter Mares

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MERNDA STRATEGY PLAN – 3.8.2 Heritage Buildings and Structures

CITY OF WHITTLESEA 1 CONTENTS 3.7.4 Drainage Functions .............................................................................................................................. 34 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 4 3.8 Heritage & culture ......................................................................................................................... 36 3.8.1 Aboriginal Archaeological Sites ............................................................................................................ 36 2.0 UNDERSTANDING AND USING THE MERNDA STRATEGY PLAN – 3.8.2 Heritage Buildings and Structures ........................................................................................................ 36 INCORPORATED DOCUMENT ....................................................................................................................... 6 3.9 Servicing & drainage ..................................................................................................................... 36 3.9.1 Sewerage and water ........................................................................................................................... 36 3.0 KEY OBJECTIVES & STRATEGIC ACTIONS ................................................................. 8 3.9.2 Drainage ............................................................................................................................................... 36 3.1 Planning & Design ........................................................................................................................... -

Not Biting the Hand That Feeds

Theories for understanding government advertising in Australia Sally Young Media and Communications Program The University of Melbourne In recent weeks, there has been increased commentary on government advertising as a result of the Howard government running some controversial ads on its planned industrial relations changes. Although the full IR campaign has not yet hit full steam, it is estimated that the total campaign will cost at least $20 million and possibly even $100 million.1 This is part of a pattern which, in recent years, has seen Australian governments dramatically increase their spending on advertising—particularly on television.2 The federal government now spends at least $100 million per year on government advertising and, in 1999-00, as a result of high spending on advertising the new Goods and Services Tax (GST), spent a record $211 million.3 There are a number of theories which can help us to understand this trend and these originate from a range of disciplinary perspectives including political science, legal studies, media and journalism studies. Each suggests conceptual frameworks for analysing this phenomenon and each emphasises different aspects of the problem. 1 Schubert, Misha, 2005, ‘Work law ad blitz may cost $100m’, the Age, 5 August. 2 Young, Sally, 2004, The Persuaders: Inside the Hidden Machine of Political Advertising, North Melbourne, Pluto Press, pp.122-39. 3 Grant, Richard, 2003-04, ‘Research Note no.62 2003-04: Federal government advertising’, Canberra, Parliamentary Library, Parliament of Australia. -

15 February 2008

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Official Hansard 20TH ANNIVERSARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE SYSTEM FRIDAY, 15 FEBRUARY 2008 CANBERRA BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Friday, 15 February 2008 HOR COMMS 1 Seminar commenced at 9.05 am Participants ANDREWS, The Hon. Kevin, MP BARRIE, Mr Keith DUNCAN, Mr Tom HALLIGAN, Professor John HARRIS, Mr Ian, AO HAWKER, Mr David, MP HULL, Mrs Kay, MP JACOBS, Professor Kerry JENKINS, The Hon. Harry, MP LANGMORE, Professor John LARKIN, Dr Philip LEYNE, Ms Siobhan LINDELL, Professor Geoffrey MARSH, Professor Ian MARTIN, Professor the Hon. Stephen MONK, Mr David SAWFORD, Mr Rod STEPHENS, The Hon. Tom THOMSON, Mr Kelvin, MP WEBBER, Ms Robyn ZAPPIA, Mr Tony 20TH ANNIVERSARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEES HOR COMMS 2 Friday, 15 February 2008 The SPEAKER—Members of the Commonwealth Parliament of Australia, members of state and territory parliaments, ladies and gentlemen, friends one and all: this morning I have the great pleasure of welcoming you to a seminar to mark 20 years of the operation of the House of Representatives system of general purpose standing committees. Some have said that, at the end of the sort of week we have had in this place, perhaps this is the last thing I would want to do. Can I say most definitely that this is something that I would not have missed because if there is anything that has driven me over 22 years as a member of the House of Representatives it has been very much the work of the committees. I would like to add to what I believe others will say: our committee system in the House is much undervalued. -

July 2021 Circular Viewable

Box 2446 GPO Melbourne 3001 Affiliated with Issued free to members CIRCULAR www.melbournewalkingclub.org JULY 2021 JULY WALKS Monday 5 Patterson Rd – Cape Schanck Jim Smith Wednesday 7 Mt Evelyn – Lilydale Stn Tony Cagney Sunday 11 Crossroads – Sailors Creek Rd Kim Rosen Wednesday 14 Olinda – Boronia Oliver Lucas Sunday 18 Mt Donna Buang CANCELLED Sunday 18 Kalorama – Mt Evelyn Jenny Hosking 3rd Wed 21 Yarran Dheran – Mullum Creek Graeme Barker Sunday 25 Sailors Creek Rd – Daylesford Kim Rosen Monday 26 Mernda Stn – Hawkstowe Stn Gordon Proudfoot Wednesday 28 Heidelberg – Doncaster Charlie Freedman Copy for August to: Charlie Freedman - Phone: 0415 558 249 email: [email protected] by the 1st Wednesday in the month, 7th July. Submissions may be edited for space and other considerations. Laughter Is The Best Medicine Do you remember the times you walk into a spider web, and suddenly turn into a karate master. Visitors Fee A $5.00 fee is now charged to all visitors attending club walks. Walk leaders are to collect the cash from each visitor. Trevor Rosen, President. Extreme Conditions & Fire Bans On days of EXTREME WEATHER CONDITIONS leaders may cancel the activity at their discretion. If a day of TOTAL FIRE BAN is declared in a walk area, ALL outdoor activities in that area are CANCELLED . 1 July 2021 Office Bearers 2020 -2021 Club Executive President: Trevor Rosen General Committee: Kim Rosen, Senior Vice President: Charlie Freedman David Jones, & Secretary: Michael Corrigan Richard Simpson Assistant Secretary: Jennifer Horne -

Denying the Public's Right to Know

Denying the Public’s Right to Know A critique of the operation of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 Prepared for Kelvin Thomson MP, Shadow Minister for Public Accountability, by Michal Alhadeff, Intern, Australian National Internships Program October 2006 1 “Information about government operations is not, after all, some kind of ‘favour’ to be bestowed by a benevolent government or to be extorted from a reluctant bureaucracy. It is, quite simply, a public right.” - Bob Hawke, 1983 2 ABBREVIATIONS AAT Administrative Appeals Tribunal ALRC Australian Law Reform Commission APC Australian Press Council ARC Administrative Review Council AusAID Australian Agency for International Development AWB AWB Limited (formerly the Australian Wheat Board) DFAT Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade OFF Oil-for-Food Programme UN United Nations US United States of America $AU Australian Dollar Value 3 PREFACE The impetus for this report stemmed from a series of fruitless Freedom of Information requests submitted by Shadow Minister for Public Accountability, Kelvin Thomson MP. The requests sought the disclosure of information relating to government knowledge of the AU$290m in kickbacks funnelled to the Iraqi regime by AWB Limited (AWB). The failure of FOI laws to produce any substantive information about an issue which ignited such significant public interest compelled this study of FOI in Australia. This report is concerned solely with FOI as it relates to requests for non- personal information. There is academic consensus that treatment of this type of request provides the most telling critique of an FOI system.1 Thus Thomson’s AWB-related claims, being contentious and topical, provide an appropriate case study through which to consider Australia’s FOI regime. -

Plenty Gorge Park Draft Master Plan Summary Document

Stages and Timing Plenty Gorge Park The engagement and development of the master plan is divided into Draft Master Plan five phases, with approximate dates summarised below: Summary Document Phase 1 (complete) Background Analysis and Initial Engagement Period Community Engagement November 2017 Phase 2 (complete) Vision, Principles and Concept Plan Community Engagement Phase 3a (mid 2017) Draft Master Plan - Preparation Phase 3b (current) Draft Master Plan Community Engagement Phase 4 (early 2018) Master Plan Finalisation Phase 5 (2018) Approval and release More information Parks Victoria www.parks.vic.gov.au or call 13 1963 Vision Key objectives Plenty Gorge Park will provide diverse visitor experiences, reflect community interests and cherish the The master plan outlines three key Objective 2 heritage and nature within the unique geological setting of Plenty Gorge. objectives, each containing specific actions Increase park awareness and involvement necessary to achieve the vision for Plenty Gorge Park. The following proposed actions Improve Nioka Bush Camp and increase are considered priorities. use by the Traditional Owners and various About the park community and school groups. Located only 20km north of Melbourne, Objective 1 Develop and implement a mountain bike Plenty Gorge Park extends 11km along the Improve access and connections trail plan in collaboration with local groups Plenty River from Mernda to Bundoora. to rationalise trails and protect significant Proposed Mayeld The action of the river over time hasMernda led to X vegetation, habitat, and cultural values. Station Complete the 21km Plenty River Trail BRID the dramatic landforms found throughout GE INN R Mernda D to link visitor sites and to provide important the gorge, which make the park popular for walking and cycling access between Prepare a wayfinding and interpretation i nature-based recreational activities. -

Protecting the Future: Federal Leadership for Australia's

PROTECTING THE FUTURE Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment This research paper is a project of the Chifley Research Centre, the official think tank of the Australian Labor Party. This paper has been prepared in conjunction with the Labor Environment Action Network (LEAN). The report is not a policy document of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party. Publication details: Wade, Felicity. Gale, Brett. “Protecting the Future: Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment” Chifley Research Centre, November 2018. PROTECTING THE FUTURE Federal Leadership for Australia’s Environment FOREWORD Australians are immensely proud of our natural environment. From our golden beaches to our verdant rainforests, Australia seems to be a nation blessed with an abundance of nature’s riches. Our natural environment has played a starring role in Australian movies and books and it is one of our key selling points in attracting tourists down under. We pride ourselves on our clean, green country and its contrast to many other places around the world. Why is it then that in recent decades pride in our The mission of the Chifley Research Centre (CRC) is to natural environment has very rarely translated into champion a Labor culture of ideas. The CRC’s policy action to protect it? work aims to set the groundwork for a fairer and more progressive Australia. Establishing a long-term agenda We have one of the highest rates of fauna extinctions for solving societal problems for progressive ends in the world, globally significant rates of deforestation, is a key aspect of the work undertaken by the CRC. plastics clogging our waterways, and in many regions, The research undertaken by the CRC is designed to diminishing air, water and soil quality threaten human stimulate public policy debate on issues outside of day wellbeing and productivity. -

Australia's Relations with Iran

Policy Paper No.1 October 2013 Shahram Akbarzadeh ARC Future Fellow Australia’s Relations with Iran Policy Paper 1 Executive summary Australia’s bilateral relations with Iran have experienced a decline in recent years. This is largely due to the imposition of a series of sanctions on Iran. The United Nations Security Council initiated a number of sanctions on Iran to alter the latter’s behavior in relation to its nuclear program. Australia has implemented the UN sanctions regime, along with a raft of autonomous sanctions. However, the impact of sanctions on bilateral trade ties has been muted because the bulk of Australia’s export commodities are not currently subject to sanctions, nor was Australia ever a major buyer of Iranian hydrocarbons. At the same time, Australian political leaders have consistently tried to keep trade and politics separate. The picture is further complicated by the rise in the Australian currency which adversely affected export earnings and a drought which seriously undermined the agriculture and meat industries. Yet, significant political changes in Iran provide a window of opportunity to repair relations. Introduction Australian relations with the Islamic Republic of Iran are complicated. In recent decades, bilateral relations have been carried out under the imposing shadow of antagonism between Iran and the United States. Australia’s alliance with the United States has adversely affected its relations with Iran, with Australia standing firm on its commitment to the United States in participating in the War on Terror by sending troops to Afghanistan and Iraq. Australia’s continued presence in Afghanistan, albeit light, is testimony to the close US-Australia security bond. -

Yan Yean Road Duplication (Stage 2)

s YAN YEAN ROAD DUPLICATION (STAGE 2) LAND USE AND PLANNING ASSESSMENT Prepared on behalf of: MRPV 20 November 2020 © Urbis Pty Ltd 50 105 256 228 urbis.com.au CONTENTS Land Use and Planning Assessment .................................................................................................. 1 1. introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Overview .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Qualifications and experience .............................................................................................. 1 2. Summary of key issues, Opinions and recommendations ........................................................... 2 2.1. Key land use Impacts........................................................................................................... 2 2.1.1. Key Issues ............................................................................................................ 2 2.1.2. Opinions and Recommendations ......................................................................... 2 2.2. Declaration ........................................................................................................................... 6 3. Project description ............................................................................................................................ 7 4. Existing land use Context ............................................................................................................... -

Offset Management Plan: 60 Watts Road, Yan Yean, Victoria (EPBC 2016/7674)

Redacted version. Personal affairs information has been redacted for publication. Final Report Offset Management Plan: 60 Watts Road, Yan Yean, Victoria (EPBC 2016/7674) Prepared for Level Crossing Removal Project April 2019 Ecology and Heritage Partners Pty Ltd MELBOURNE: 292 Mt Alexander Road, Ascot Vale VIC 3032 GEELONG: 230 Latrobe Terrace, Geelong West Vic 3218 BRISBANE: Level 22, 127 Creek Street, Brisbane QLD 4000 ADELAIDE: 22 Greenhill Road, Wayville SA 5034 CANBERRA: PO Box 6067, O’Connor ACT 2602 SYDNEY: Level 5, 616 Harris Street, Ultimo, NSW, 2007 www.ehpartners.com.au | (03) 9377 0100 DOCUMENT CONTROL Assessment EPBC 2016/7674: Offset Management Plan Address 60 Watts Road, Yan Yean, Victoria Project number Project manager Report reviewer Mapping File name Client Level Crossing Removal Project a division of Major Transport Infrastructure Authority Bioregion Victorian Volcanic Plain CMA Port Phillip and Westernport Council Whittlesea Council Comments updated Report versions Comments Date submitted by Draft 19/02/2019 Draft V2 12/04/2019 Final 29/04/2019 Acknowledgements We thank the following people for their contribution to the project: Level Crossing Removal Project for project information; The Department of the Environment and Energy for providing comments on the draft Plan; and The Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning for access to ecological databases. Copyright © Ecology and Heritage Partners Pty Ltd This document is subject to copyright and may only be used for the purposes for which it was commissioned. The use or copying of this document in whole or part without the permission of Ecology and Heritage Partners Pty Ltd is an infringement of copyright. -

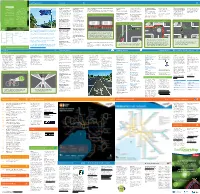

Travelsmart Map (PDF 1.3MB)

Getting around Cycling On the road www.ptv.vic.gov.au applicable laws. laws. applicable timetables visit visit timetables Is a bicycle a legal road Is it OK to drive a car in a Who is at fault when a car door is opened into the path of Is it legal to ride two of the tram until the doors Do I need to signal all stopping, but you may Why do some signalised Drivers of motor vehicles may equipment and follow any any follow and equipment transport information and and information transport abreast? close and the road is free of turns when I’m riding my choose to signal at these intersections have special be fined for allowing any part abilities, wear protective protective wear abilities, For up-to-date public public up-to-date For vehicle? bicycle lane? someone on a bike? Yes, but you must not ride crossing pedestrians. This bike? times to let other traffic know waiting boxes for bikes? of their vehicle to enter the sense. Stay within your your within Stay sense. Yes, bicycles are classified as Only for 50 metres or less The car driver or passenger who opens the door is at fault and can more than 1.5 metres apart. rule is the same whether you You are required to give a what you’re doing. These line markings are designated bike area whilst undertaken using common common using undertaken the time of printing. of time the vehicles under the Victorian and only in the following be fined. ‘Car dooring’ can cause life-threatening injuries to cyclists. -

Victorian Heritage Database Place Details - 27/9/2021 MERNDA 3, PLENTY RIVER FLUME

Victorian Heritage Database place details - 27/9/2021 MERNDA 3, PLENTY RIVER FLUME Location: YAN YEAN PIPE TRACK MERNDA, Whittlesea City Heritage Inventory (HI) Number: H7922-0038 Listing Authority: HI Heritage Inventory Citation High. Has been listed on Govt Buildings register and classified by Nat Trust. Statement of Significance: The Plenty River Flume is part of the Yan Yean Water Supply System and originally supplied water to Melbourne. The flume was constructed in 1879 to replace an old damaged bridge which formed part of the Morang Aqueduct and carried water from the Yan Yean Reservoir to a small storage basin known as the pipe- head reservoir. The flume was designed by engineer William Davidson and is supported by three basalt piers which were locally quarried and hewn. Each pier has a clean, dressed cutwater to cope with the Plenty River floods and has coursed face basalt blockwork abutments with dressed basalt cappings. The flume itself is of bolted wrought iron plate construction, approximately 1.5 by 1.2 metres and 70 metres long. There is a set of rollers above each basalt column to accommodate expansion and contraction of the metal flume. The flume is no longer used and whilst now uncovered, was covered with timber when in use. The Plenty River Flume is of historical and architectural importance to the State of Victoria. The Plenty River Flume is of historical importance for its association with the supply of reticulated water to Melbourne from the Yan Yean Reservoir. The Yan Yean reservoir and its associated structures are of exceptional importance as the earliest metropolitan water supply system in Victoria and its construction represented a major engineering feat in the late 1850s.