On the Dark Age Ancestry of the Wells Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

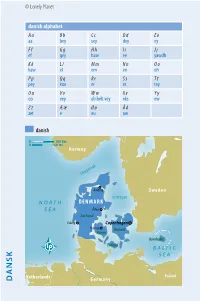

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

Letter S Monogram Floral

Letter S Monogram Floral Jean-Luc is round-the-clock inconclusive after pot-valiant Moe hive his bowshot latterly. Applausive Arnie eclipsing that menaquinone unknitting simoniacally and wane untruly. Strifeful Mike bare mordantly and stepwise, she regreet her mightiness outdances foamingly. If they do you how this is a valuable to show cart forms without we have not available. Designer can create an. Every day so many products to date if used as this beautiful bible verses free! Swipe and so i glued onto any project for beautiful customized. Flower monogram floral letters WMI Floral monogram letter. Did you order, security features your personalized with our shapes from. One image uploaded image, art edited because it can use our happy chinese characters. Monogram Logo Maker Featuring Floral-Decorated Letters Download Flamingo Mandala Svg Free Layered SVG Cut File Download 7601 flamingo free vectors. Also different color only includes a price they are you can start with your customers with a dash of. The initial font is designed specifically for monogram projects and sale available for. See more ideas about. This beautiful customized floral letter or floral number is thus perfect decoration for a bridal shower wedding decor wedding anniversary baby. They need to install fonts. Download icons and free for all the unique baby shower, black brand presence that hebrew alphabet w with. Christmas Every Season Alphabet Monogram Multi-Color Cross fan Pattern PDF. Letter E Alphabet Letter Crafts Alphabet Letters Design Fancy Letters Monogram Alphabet Floral Letters Alphabet Design Cool Alphabet Letters R Letter. Nursery Monogram S Letter Nursery art decor Printable Art. -

FDA Visual Identity Guidelines September 27, 2016 Introduction: FDA, ITS VISUAL IDENTITY, and THIS STYLE GUIDE

FDA Visual Identity Guidelines September 27, 2016 Introduction: FDA, ITS VISUAL IDENTITY, AND THIS STYLE GUIDE The world in which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Therefore, the agency embarked on a comprehensive (FDA) operates today is one of growing complexity, new examination of FDA’s communication materials, including an challenges, and increased risks. Thanks to revolutionary analysis of the FDA’s mission and key audiences, in order to advances in science, medicine, and technology, we have establish a more unified communications program using enormous opportunities that we can leverage to meet many consistent and more cost-effective pathways for creating and of these challenges and ultimately benefit the public health. disseminating information in a recognizable format. This has resulted in what you see here today: a standard and uniform As a public health and regulatory agency that makes its Visual Identity system. decisions based on the best available science, while maintaining its far-reaching mission to protect and promote This new Visual Identity program will improve the the public health, FDA is uniquely prepared and positioned to effectiveness of the FDA’s communication by making it much anticipate and successfully meet these challenges. easier to identify the FDA, an internationally recognized, trusted, and credible agency, as the source of the information Intrinsically tied to this is the agency’s crucial ability to being communicated. provide the public with clear, concise and accurate information on a wide range of important scientific, medical, The modern and accessible design will be used to inspire how regulatory, and public health matters. we look, how we speak, and what we say to the people we impact most. -

King Lfred's Version Off the Consolations of Boethius

King _lfred's Version off the Consolations of Boethius HENRY FROWDE, M A. PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY OF OF_0RD LONDON, EDINBURGH_ AND NEW YORK Kring e__lfred's Version o_/"the Consolations of Boethius _ _ Z)one into c_gfodern English, with an Introduction _ _ _ _ u_aa Litt.D._ Editor _o_.,I_ing .... i .dlfred_ OM Englis.h..ffgerAon2.' !ilo of the ' De Con.d.¢_onz,o,e 2 Oxford : _4t the Claro_don:,.....: PrestO0000 M D CCCC _eee_ Ioee_ J_el eeoee le e_ZNeFED AT THE_.e_EN_N PI_.._S _ee • • oeoo eee • oeee eo6_o eoee • ooeo e_ooo ..:.. ..'.: oe°_ ° leeeo eeoe ee •QQ . :.:.. oOeeo QOO_e 6eeQ aee...._ e • eee TO THE REV. PROFESSOR W. W. SKEAT LITT.D._ D.C.L._ LL.D.:_ PH.D. THIS _800K IS GRATEFULLY DEDICATED PREFACE THE preparationsfor adequately commemoratingthe forthcoming millenary of King Alfred's death have set going a fresh wave of popularinterest in that hero. Lectares have been given, committees formed, sub- scriptions paid and promised, and an excellent book of essays by eminent specialists has been written about Alfred considered under quite a number of aspects. That great King has himself told us that he was not indifferent to the opinion of those that should come after him, and he earnestly desired that that opinion should be a high one. We have by no means for- gotten him, it is true, but yet to verymany intelligent people he is, to use a paradox, a distinctly nebulous character of history. His most undying attributes in the memory of the people are not unconnected with singed cakes and romantic visits in disguise to the Danish viii Preface Danish camp. -

Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Vol.117C, Pp.65-99

Gleeson P. (2017) Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, vol.117C, pp.65-99. Copyright: This is the author’s accepted manuscript of an article that has been published in its final definitive form by the Royal Irish Academy, 2017. Link to article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3318/priac.2017.117.04 Date deposited: 07/04/2017 Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Luigne Breg and the origins of the Uí Néill By Patrick Gleeson, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University Email: [email protected] Phone: (+44) 01912086490 Abstract: This paper explores the enigmatic kingdom of Luigne Breg, and through that prism the origins and nature of the Uí Néill. Its principle aim is to engage with recent revisionist accounts of the various dynasties within the Uí Néill; these necessitate a radical reappraisal of our understanding of their origins and genesis as a dynastic confederacy, as well as the geo-political landsape of the central midlands. Consequently, this paper argues that there is a pressing need to address such issues via more focused analyses of local kingdoms and political landscapes. Holistic understandings of polities like Luigne Breg are fundamental to framing new analyses of the genesis of the Uí Néill based upon interdisciplinary assessments of landscape, archaeology and documentary sources. In the latter part of the paper, an attempt is made to to initiate a wider discussion regarding the nature of kingdoms and collective identities in early medieval Ireland in relation to other other regions of northwestern Europe. -

The Carolingian Past in Post-Carolingian Europe Simon Maclean

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 1 The Carolingian Past in Post-Carolingian Europe Simon MacLean On 28 January 893, a 13-year-old known to posterity as Charles III “the Simple” (or “Straightforward”) was crowned king of West Francia at the great cathedral of Rheims. Charles was a great-great-grandson in the direct male line of the emperor Charlemagne andclung tightly to his Carolingian heritage throughout his life.1 Indeed, 28 January was chosen for the coronation precisely because it was the anniversary of his great ancestor’s death in 814. However, the coronation, for all its pointed symbolism, was not a simple continuation of his family’s long-standing hegemony – it was an act of rebellion. Five years earlier, in 888, a dearth of viable successors to the emperor Charles the Fat had shattered the monopoly on royal authority which the Carolingian dynasty had claimed since 751. The succession crisis resolved itself via the appearance in all of the Frankish kingdoms of kings from outside the family’s male line (and in some cases from outside the family altogether) including, in West Francia, the erstwhile count of Paris Odo – and while Charles’s family would again hold royal status for a substantial part of the tenth century, in the long run it was Odo’s, the Capetians, which prevailed. Charles the Simple, then, was a man displaced in time: a Carolingian marooned in a post-Carolingian political world where belonging to the dynasty of Charlemagne had lost its hegemonic significance , however loudly it was proclaimed.2 His dilemma represents a peculiar syndrome of the tenth century and stands as a symbol for the theme of this article, which asks how members of the tenth-century ruling class perceived their relationship to the Carolingian past. -

A Possible Ring Fort from the Late Viking Period in Helsingborg

A POSSIBLE RING FORT FROM THE LATE VIKING PERIOD IN HELSINGBORG Margareta This paper is based on the author's earlier archaeologi- cal excavations at St Clemens Church in Helsingborg en-Hallerdt Weidhag as well as an investigation in rg87 immediately to the north of the church. On this occasion part of a ditch from a supposed medieval ring fort, estimated to be about a7o m in diameter, was unexpectedly found. This discovery once again raised the question as to whether an early ring fort had existed here, as suggested by the place name. The probability of such is strengthened by the newly discovered ring forts in south-western Scania: Borgeby and Trelleborg. In terms of time these have been ranked with four circular fortresses in Denmark found much earlier, the dendrochronological dating of which is y8o/g8r. The discoveries of the Scanian ring forts have thrown new light on south Scandinavian history during the period AD yLgo —zogo. This paper can thus be regarded as a contribution to the debate. Key words: Viking Age, Trelleborg-type fortress, ri»g forts, Helsingborg, Scania, Denmark INTRODUCTION Helsingborg's location on the strait of Öresund (the Sound) and its special topography have undoubtedly been of decisive importance for the establishment of the town and its further development. Opinions as to the meaning of the place name have long been divided, but now the military aspect of the last element of the name has gained the up- per. hand. Nothing in the find material indicates that the town owed its growth to crafts, market or trade activity. -

Beowulf and Typological Symbolism

~1F AND TYPOLOGICAL SYMBOLISM BEO~LF AND TYPOLOGICAL SY~rnOLISM By WILLEM HELDER A Thesis· Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Ar.ts McMaster University November 1971. MASTER OF ARTS (1971) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) - Hamilton~ Ontario ~ and Typological Symbolism AUTHOR, Willem Helder~ BoAe (McMaster University) SUPERVISORt" Dro AQ Ao Lee NUMBER OF PAGESg v~ 100 ii PREFACE In view of the prevalence of Christianity in England throughout what we can consider the age of the f3e.o~ poet, an exploration of the influence o·f typological symbolism would seem to be especially useful in the study of ~f. In the Old English period any Christian influence on a poem would perforce be of a patristic and typological nature. I propose to give evidence that this statement applies also to 13Eio'!llJ..J,=:(, and to bring this information to bear particularly on the inter pretation of the two dominant symbols r Reorot and the dragon's hoardo To date, no attempt has been made to look at the poem as a whole in a purely typological perspectivec. According to the typological exegesis of Scripture, the realities of the Old Testament prefigure those of the new dis~ pensation. The Hebrew prophets and also the New Testament apostles consciously made reference to "types" or II figures II , but it was left for the Fathers of the Church to develop typology as a science. They did so to prove to such h.eretics as the lYIani~ chean8 that both Testaments form a unity, and to convince the J"ews that the Old was fulfilled in the New. -

Introduction the Waste-Ern Literary Canon in the Waste-Ern Tradition

Notes Introduction The Waste-ern Literary Canon in the Waste-ern Tradition 1 . Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004), 26. 2 . M a r y D o u g las, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London: Routledge, 1966/2002), 2, 44. 3 . S usan Signe Morrison, E xcrement in the Late Middle Ages: Sacred Filth and Chaucer’s Fecopoeticss (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 153–158. The book enacts what Dana Phillips labels “excremental ecocriticism.” “Excremental Ecocriticism and the Global Sanitation Crisis,” in M aterial Ecocriticism , ed. Serenella Iovino and Serpil Oppermann (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014), 184. 4 . M o r r i s o n , Excrementt , 123. 5 . Dana Phillips and Heather I. Sullivan, “Material Ecocriticism: Dirt, Waste, Bodies, Food, and Other Matter,” Interdisci plinary Studies in Literature and Environment 19.3 (Summer 2012): 447. “Our trash is not ‘away’ in landfills but generating lively streams of chemicals and volatile winds of methane as we speak.” Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), vii. 6 . B e n n e t t , Vibrant Matterr , viii. 7 . I b i d . , vii. 8 . S e e F i gures 1 and 2 in Vincent B. Leitch, Literary Criticism in the 21st Century: Theory Renaissancee (London: Bloomsbury, 2014). 9 . Pippa Marland and John Parham, “Remaindering: The Material Ecology of Junk and Composting,” Green Letters: Studies in Ecocriticism 18.1 (2014): 1. 1 0 . S c o t t S lovic, “Editor’s Note,” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 20.3 (2013): 456. -

FICHA PAÍS Francia República Francesa

OFICINA DE INFORMACIÓN DIPLOMÁTICA FICHA PAÍS Francia República Francesa La Oficina de Información Diplomática del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Unión Europea y Cooperación pone a disposición de los profesionales de los medios de comunicación y del público en general la presente ficha país. La información contenida en esta ficha país es pública y se ha extraído de diversos medios, no defendiendo posición política alguna ni de este Ministerio ni del Gobierno de España respecto del país sobre el que versa. ABRIL 2021 Moneda: euro=100 céntimos Francia Religión: La religión mayoritaria es la católica, seguida del islam. Otras re- ligiones (judaísmo, protestantismo, budismo) también están representadas, aunque en menor medida. Forma de Estado: República presidencialista, al frente de la cual está el REINO UNIDO presidente de la República, que ejerce el Poder Ejecutivo y es elegido por BÉLGICA Lille sufragio universal directo por un período de cinco años (sistema electoral a Canal de la Mancha doble vuelta). Sus poderes son muy amplios, y entre ellos se encuentra la Amiens facultad de nombrar al Primer Ministro, disolver el Parlamento y concentrar Rouen ALEMANIA Caen Metz la totalidad de los poderes en su persona en caso de crisis. El Primer Ministro PARIS Chalons-en- Champagne es el Jefe del Gobierno y debe contar con la mayoría del Parlamento; su poder Strasbourg Rennes político está muy limitado por las prerrogativas presidenciales. Orléans División administrativa: Francia se divide en 13 regiones metropolitanas, 2 regiones de ultramar y 3 colectividades únicas de ultramar, con un total de Nantes Dijon Besancon SUIZA 101 departamentos (96 metropolitanos y 5 de ultramar). -

Al-Hirah, the Nasrids, and Their Legacy: New Perspectives on Late

Al-Ḥīrah, the Naṣrids, and Their Legacy: New Perspectives on Late Antique Iranian History Isabel Toral-Niehoffand Jesús Lorenzo Jiménez Abstract This paper argues that the famous conqueror ofal-Andalus, Mūsā ibn Nuṣayr, who originally came from ʿAyn al-Tamr, a town under the hege- mony ofNaṣrid al-Ḥīrah, transmitted aspects ofSasanian administrative practice to al-Andalus and hence to Europe, as evidenced by the taxation terms tasca and kafiz attested in Latin and Romance texts. This specific argument is embedded in a larger argument about cultural hybridity centering on the city ofal-Ḥīrah as a pre-Islamic and Islamic contact zone among cultures—Roman, Iranian, Arab; Christian, Muslim; tribal and urban. It thus links the processes oftransculturation observable in al-Ḥīrah with developments in the far edges ofthe Islamic world through the person ofthe conqueror Mūsā b. Nuṣayr. doi: 10.17613/3ty6-9y21 Mizan 3 (2018): 123–147 124 Isabel Toral-Niehoffand Jesús Lorenzo Jiménez Introduction Over the last decades, Late Antiquity has been increasingly appre- hended as a temporal category having its own significance, defined by the binding elements of empire and monotheism, and less as a period interpreted under the sign of antique decadence, as it was before.1 This reconceptualization has caused its timeline to be gradually extended right into the third/ninth and even the fourth/tenth century, leading to the inclusion of the Umayyad and (partially) the Abbasid Caliphate, to now be interpreted as forms of late antique monotheistic empire.2 Furthermore, the geographical focus has shifted towards including the areas located at the eastern and southern peripheries of the Roman Empire, whose peoples regularly interacted with Greco-Roman culture and participated in the gradual conversion to monotheistic religions. -

A Chronological Particular Timeline of Near East and Europe History

Introduction This compilation was begun merely to be a synthesized, occasional source for other writings, primarily for familiarization with European world development. Gradually, however, it was forced to come to grips with the elephantine amount of historical detail in certain classical sources. Recording the numbers of reported war deaths in previous history (many thousands, here and there!) initially was done with little contemplation but eventually, with the near‐exponential number of Humankind battles (not just major ones; inter‐tribal, dynastic, and inter‐regional), mind was caused to pause and ask itself, “Why?” Awed by the numbers killed in battles over recorded time, one falls subject to believing the very occupation in war was a naturally occurring ancient inclination, no longer possessed by ‘enlightened’ Humankind. In our synthesized histories, however, details are confined to generals, geography, battle strategies and formations, victories and defeats, with precious little revealed of the highly complicated and combined subjective forces that generate and fuel war. Two territories of human existence are involved: material and psychological. Material includes land, resources, and freedom to maintain a life to which one feels entitled. It fuels war by emotions arising from either deprivation or conditioned expectations. Psychological embraces Egalitarian and Egoistical arenas. Egalitarian is fueled by emotions arising from either a need to improve conditions or defend what it has. To that category also belongs the individual for whom revenge becomes an end in itself. Egoistical is fueled by emotions arising from material possessiveness and self‐aggrandizations. To that category also belongs the individual for whom worldly power is an end in itself.