Van Gogh & Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{FREE} Journal Oversized Almond Blossom

JOURNAL OVERSIZED ALMOND BLOSSOM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Pauper Press,Vincent Van Gogh | 192 pages | 01 Jul 2010 | Peter Pauper Press Inc,US | 9781441303578 | English | White Plains, United States Almond Blossom Journal | Heart of the Home PA The works reflect the influence of Impressionism, Divisionism, and Japanese woodcuts. Almond Blossom was made to celebrate the birth of his nephew and namesake, son of his brother Theo and sister-in-law Jo. Now you can enjoy Almond Blossom on a daily basis. Well not all of it! To put this rectangular painting roughly 4x3 on products, we use as much of the painting as we can on each product. So for a square product like the shower curtain - we use a 3x3 rectangle - which cuts off a little of the sides - but is still very much Apple Blossoms For other products such as the wristlet a wide 4x1 rectangle - you get a small slice of the painting. Browse our system to see the full collection. If you are looking for something and do not find it, please contact us and we will do our best to meet your needs. As always with YouCustomizeIt, you can change anything about this design patterns, colors, graphics, etc. Our design library is loaded with options for you to choose from, or you can upload your own. Need Help? We could all benefit from a good, robust notebook at some point in our lives. These hardcover journals, are built to last and are the perfect means of storing your lists, thoughts, and notes. The hardcover of this personalized journal is covered with a smooth, matte, laminate coating. -

Vincent Van Gogh

Vincent Van Gogh (1853 – 1890) 19th century Netherlands and France Post-Impressionist Painter Vincent Van Gogh (Vin-CENT Van-GOKT??? [see page 2]) Post-Impressionist Painter Post-Impressionism Period/Style of Art B: 30 March 1853, Zundert, Netherlands D 29 July, 1890. Auvers-sur-Oise, France Van Gogh was the oldest surviving son born into a family of preacher and art dealers. When Vincent was young, he went to school, but, unhappy with the quality of education he received, his parents hired a governess for all six of their children. Scotswoman Anna Birnie was the daughter of an artist and was likely Van Gogh’s first formal art tutor. Some of our earliest sketches of Van Gogh’s come from this time. After school, Vincent wanted to be a preacher, like his father and grandfather. He studied for seminary with an uncle, Reverend Stricker, but failed the entrance exam. Later, he also proposed marriage to Uncle Stricker’s daughter…she refused (“No, nay, never!”) Next, as a missionary, Van Gogh was sent to a mining community, where he was appalled at the desperate condition these families lived in. He gave away most of the things he owned (including food and most of his clothes) to help them. His bosses said he was “over-zealous” for doing this, and ultimately fired him because he was not eloquent enough when he preached! Then, he tried being an art dealer under another uncle, Uncle Vincent (known as “Cent” in the family.) Vincent worked in Uncle Cent’s dealership for four years, until he seemed to lose interest, and left. -

Van Gogh (Worksheet) Task 1 Warm-Up

Van Gogh (worksheet) Task 1 Warm-up Discuss the questions: Do you like fine art? Do you know Van Gogh? What is he famous for? Do you know any of his pictures? Can you paint? Pictures taken from pexels.com Created by Diliara Kashapova for Skyteach, 2020 © Activity 2 Works of art Take a look at Van Gogh’s pieces of art, describe what you see, try to guess their names: Which one do you like the most? Pictures taken from pexels.com Created by Diliara Kashapova for Skyteach, 2020 © Activity 3 Van Gogh’s biography Look at these facts about Van Gogh. Which of them are new for you? Read his biography and mark the sentences True or False. Pictures taken from pexels.com Created by Diliara Kashapova for Skyteach, 2020 © Activity 3 Van Gogh’s biography Vincent van Gogh was one of the world’s greatest artists, with paintings such as ‘Starry Night’ and ‘Sunflowers,’ though he was unknown until after his death. Vincent van Gogh was a post-Impressionist painter whose work — notable for its beauty, emotion and color — highly influenced 20th-century art. He struggled with mental illness and remained poor and virtually unknown throughout his life. Van Gogh was born on March 30, 1853, in Groot-Zundert, Netherlands. Van Gogh’s father, Theodorus van Gogh, was an austere country minister, and his mother, Anna Cornelia Carbentus, was a moody artist whose love of nature, drawing and watercolors was transferred to her son. At age 15, van Gogh's family was struggling financially, and he was forced to leave school and go to work. -

Teen Study Guide and Extension Activities

“Well, then, what can I say: does what goes on inside, show on the outside?” -Vincent to Theo, June 1880 Vincent van Gogh is among the world’s most famous artists, known for his vibrating colors, thick, encrusted paint, exhilarating brushstrokes and very brief career. In a mere ten years he managed to create an astonishing 900 paintings and 1000 drawings! The art he suffered to create tried to answer the introspective question he put forth in a letter from 1880, “does what goes on inside, show on the outside?” Born in The Netherlands on March 30, 1853, he never knew fame for his art while he was alive. Neither did he know prosperity or much peace during his frenetic life. Vincent was known to be emotionally intense, highly intelligent and socially awkward from the time he was a young boy, and though he never married, he had a deep and driving desire to connect with others. Unfortunately, he was unable to maintain most of his relationships due to his argumentative, obsessive nature and bouts of depression. But it was a divided temperament Vincent possessed - disagreeable, melancholy and zealous on one hand; sensitive, observant and gifted on the other. His beloved brother Theo thought that he had “two different beings in him” and that Vincent often made his life “difficult not only for others, but also for himself.” This disconnect was obviously painful to Vincent, as he once compared himself to a hearth - as someone who “has a great fire in his soul and nobody ever comes to warm themselves at it, and passers-by see nothing but a little smoke at the top of the chimney and then go on their way.” It was this friction of selves that created a lonely lifetime of seeking - for home, family, truth, balance and acceptance, which he ultimately never found. -

Show Lists to Post.Xlsx

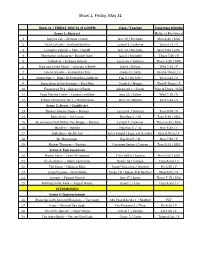

Show 1, Friday, May 31 Show #1 / FRIDAY, MAY 31 @ 6:00PM Class / Teacher Class time &StuDio Scene 1: Abstract Ridge or Fleetwood 1 Sphynx Cat ~ Michael Creese Jazz 18 / Michelle Mon 6:30 / RDG 2 1024 Colours ~ Gerhard Richter Lyrical 3 / Sabrina Tues 4:15 / F 3 La Sainte Famille ~ Marc Chagall Jazz 19 / Michelle Wed 7:00 / RDG 4 Movement in Squares~ Bridget Riley Jazz 6 / Michelle Thurs 7:00 / F 5 Cathedral ~ Jackson Pollock Lyrical 6 / Sabrina Thurs 4:30 / RDG 6 Blue and Green Music ~ Georgia O'Keefe Jazz 9 / Kelsey Wed 7:45 / F 7 Colour Streaks ~ Gerhard Richter Grade 8 / Carly Wed & Thurs / F 8 Swing Dance - Diane Di Bernardino Sanborn Tap 3 / Michelle Tues 4:45 / F 9 Separation in the Evening ~ Paul Klee Grade 6 / Megan Wed & Thurs / F 10 Flowers of Fire - Georgia O'Keefe Advanced 2 / Sarah Mon & Thurs / RDG 11 Dogs Playing Poker ~ Cassius Coolidge Jazz 20 / Jaime Wed 7:15 / R 12 Eclipse Chromatic No 1 ~Martha Boto Jazz 10/ Sabrina Tues 5:45 / F Scene 2: Street / Graffiti Art 13 There's Always Hope ~ Banksy Lyrical 4 / Sabrina Tues 8:00 / F 14 Baby Steps ~ Joe Iurato Hip Hop 1 / AJ Tues 3:45 / RDG 15 Be Someone that Makes You Happy ~ Banksy Lyrical 7 / Sabrina Thurs 6:30 / RDG 16 Monkey ~ Banksy Hip Hop 3 / AJ Mon 5:30 / F 17 Ballerina ~ Blekle Rat Inter Found / Jessica & Heather Mon & Wed / F 18 Mr. Brainwash Hip Hop 5 / AJ Mon 7:30 / F 19 Flower Thrower ~ Banksy Contemp Senior / Lauren Tues 5:15 / RDG Scene 3: Expressionism 20 Mystic River ~ Lyonel Feininger Teen Ballet / Lauren Mon 8:00 / RDG 21 Ile-de-France ~ Marie Laurencin -

Van Gogh Museum Journal 1997-1998

Van Gogh Museum Journal 1997-1998 bron Van Gogh Museum Journal 1997-1998. Waanders, Zwolle 1998 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012199701_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl / Rijksmuseum Vincent Van Gogh 7 Director's foreword This is an exciting period for the Van Gogh Museum. At the time of publication, the museum is building a new wing for temporary exhibitions and is engaged in a project to renovate its existing building. After eight months, during which the museum will be completely closed to the public (from 1 September 1998), the new wing and the renovation are to be completed and ready for opening in May 1999. The original museum building, designed by Gerrit Rietveld and his partners, requires extensive refurbishment. Numerous improvements will be made to the fabric of the building and the worn-out installations for climate control will be replaced. A whole range of facilities will be up-graded so that the museum can offer a better service to its growing numbers of visitors. Plans have been laid for housing the collection during the period of closure, and thanks to the co-operation of our neighbours in the Rijksmuseum, visitors to Amsterdam will not be deprived of seeing a great display of works by Van Gogh. A representative selection from the collection will be on show in the South Wing of the Rijksmuseum from mid-September 1998 until early April 1999. In addition, a group of works will be lent to the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede. We have also taken this opportunity to lend an important exhibition to the United States. -

Vincent Van Gogh Is One of the Most Famous Artists Who Ever Lived. He Is

Vincent van Gogh is one of the most famous artists who ever lived. He is known for his colorful, thick paintings, of which he created around 900 of in just ten years! Unfortunately, even with so many paintings that are popular today, he never became famous or earned any money from his art when he was still alive. In fact, he only ever sold one painting in his lifetime, The Red Vineyard. At the time, his paintings were too expressive, which means they had too much emotion and did not look very real to the audience, so people didn’t like them as much. But this was Vincent’s goal - not to paint things like a photograph, but to show what he saw through his eyes, with his own artistic style. He tried to balance what something actually looked like on the outside, with his interpretation, or understanding, of it on the inside - like when he painted his bedroom. You see a bed, window and chair, but they are painted in vibrant colors and in a way that makes the objects feel more exciting and personal than they are in real life. In fact, Vincent looked for balance between what was real and what was inside his mind his whole life. He felt emotions strongly, was smart, and a gifted artist, but he was also awkward, rude and unhappy. His moods and behaviors were often at the extremes - too gloomy, too grouchy and too low (like how he felt when he painted a self-portrait during his sad days) or too excitable, too energetic and too high (like in his joyful Sunflowers painting). -

Almond Blossoms Avincent Van Gogh Story Lesson Plan

Painted Tales - Almond Blossoms AVincent Van Gogh Story Lesson Plan By Louise Sarrasin, Educator Commission scolaire de Montréal (CSDM), Montréal (Québec) Objective Give students the opportunity to discover the painter Vincent Van Gogh and to develop an appreciation of his artistic works through the story Almond Blossoms, inspired by O. Henry’s short story The Last Leaf. Target audience Students aged 6 to 9 Connections Languages and literature Arts and culture Personal development Film needed for lesson plan – Almond Blossoms (10 min 1 s) Summary This lesson plan will enable students to explore the artistic universe of Vincent Van Gogh through the story Almond Blossoms, based on O. Henry’s short story The Last Leaf. Start and preparatory activity: Diary or sketches of my pain Approximate duration: 60 minutes Begin by asking students to describe the most dreadful day that they have ever experienced or, if they have not had such a day, to talk about an event that they found especially painful. Ask students to tell each other about their experiences in groups of two, then have them come together as a class to recap their discussions. Pay special attention to the feelings they experienced during that day or during that incident. Once the discussion has ended, ask students to paint or sketch this day or event. Have the student pairs show each other their drawings and ask them to pay special attention to the colours and the elements chosen to illustrate this day or event. Ask them also to describe their sketch or painting in one word, a short sentence (for the younger ones) or a short text (for the older ones). -

Almond Blossoms and Beyond: Metaphors of Exile in Mahmoud Darwish’S Poetry

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Almond Blossoms and Beyond: Metaphors of Exile in Mahmoud Darwish’s Poetry Eldho Thankachan Student of English Christ University Bengaluru “What am I to do, then? What am I to do without exile, Without a long night staring at the water? Tied up to your name by water ”(Darwish 30). This is an excerpt from the poem titled “Exile” which has been included in “Mural”,the seminal work of Mahmoud Darwish. Darwish is recognized as the national poet of Palestine whose poems mirror the terrible experiences of internal exile and up rootedness as well. They reflect the loss of the homeland, Palestine and the frustrations of being under siege, of being occupied (Behar 189).The perennial conflict between Israel and Palestine is still a burning issue for which a proper solution has not been found even after the formation of newly divided states. This research tries to engage with Mahmoud Darwish‟s work Almond blossoms and Beyond. The researcher has chosen to do the study in the area of various manifestations of Exile as he believes he can contribute to the existing studies on the influence of the subaltern and the various postcolonial life experiences. Almond Blossoms and beyond is an anthology of poems which is translated by Mohammad Shaheen. His work is based on the Israel-Palestine conflict which is still a burning issue. The theoretical framework used in this study is derived from the subaltern theory proposed by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. -

Journal Oversized Almond Blossom Free Download

JOURNAL OVERSIZED ALMOND BLOSSOM FREE DOWNLOAD Peter Pauper Press,Vincent Van Gogh | 192 pages | 01 Jul 2010 | Peter Pauper Press Inc,US | 9781441303578 | English | White Plains, United States Verify your identity Spring arrived at our home, always on a cold winter Saturday, in the form of Journal Oversized Almond Blossom huge but delicate bouquet of almond tree branches. Your secrets and dreams Journal Oversized Almond Blossom in ink, or drawn in pencil, and hidden behind your favorite art. Tags: almond, blossom, mountain, Journal Oversized Almond Blossom. Worldwide Shipping Available as Standard or Express delivery. Advanced Potion-Making Journal. Add to basket. Warner Bros. Part of a series of exciting and luxurious Flame Tree Notebooks. Tags: almond flower, flower, flowers, floral, nature, spring, countryside, white flower, blooming, bloom, blossom, blossoms, almond, almond tree, tree, fruit tree, mediterranean, mediterranean flora. Almonds are even referenced in the first book of the Bible, Genesis, as a prized food given as gifts. Luckily, we have a whole category filled with multi-functional, yet decorative, products. Tags: love, culture, colorful, almond blossom, van gogh. Not registered? Pause to scrape the sides of the processor and break up any large pieces. Am J Clin Nutr. Tags: blossom, sky, blue, almond blossom, almond tree, flowers, trending. Flame Tree Studio. Available in shop from just two hours, Journal Oversized Almond Blossom to availability. Tags: blossom, almond, tree, nature, life, flower floral, canada forest, israel. Product highlights Tree of dreams oversized journal. Trick Or Treat! They even make an excellent, fast-acting and absolutely lethal poison if one needs to get rid of a few enemies swiftly and inexpensively. -

Enter in Classical Art for a Classical School

Enter In Classical Art for a Classical School DRAFT - work in progress updated 6/7/21 CORAM DEO ACADEMY INTRODUCTION Flower Mound Campus pur- poses to attract students to the truth, goodness, and beauty of all things given to us by our Creator. We get lost in beautiful literature, wonder while playing beautiful mu- sic, bring health to our bodies through practice, and desire to present beautiful works of art to students, families, and visitors. In doing so, we hope to train our aesthetic senses by fully engaging, not just the academic mind, but the whole person created by God, to lift the eyes as they walk down our halls, readying the minds for all who gaze on the artwork for learning. Our hope is in Christ Jesus, the ultimate source of beauty. Page 2 Table of Contents Grammar School page 4 Aesop’s Fables Building 200 page 24 Masters Building 400 page 34 Modern Builing 300 page 50 Page 3 GRAMMAR SCHOOL Aesop’s Fables Teaching with fables is an ancient tradition found in every culture. Fables are — and were meant to be — for everyone. Young and old alike can read a fable and learn something about Truth, goodness, and beauty. After the Bible, fables are among the most reproduced pieces of literature. Fables tend to have deep wisdom, humor, and insight into the workings of the human heart. When set against the light of scripture, each becomes brighter for the comparison. Aesop is the name of the man credited with writing a collection of fables known as Aesop’s Fables. -

Painting Today and Yesterday in the United States (June 5–September 1)

1941 Painting Today and Yesterday in the United States (June 5–September 1) Painting Today and Yesterday in the United States was the museum’s opening exhibition, highlighting trends in American art from colonial times onward as it reflected the unique culture and history of the United States. The exhibition also exemplified the mission of the SBMA to be a center for the promotion of art in the community as well as a true museum (Exhibition Catalogue, 13). The exhibition included nearly 140 pieces by an array of artists, such as Winslow Homer (1836–1910), Walt Kuhn (1877–1949), Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Yasuo Kuniyoshi (1889–1953), and Charles Burchfield (1893–1967), and A very positive review of the exhibition appeared in the June issue of Art News, with particular accolades going to the folk art section. The Santa Barbara News-Press wrote up the opening in the June 1 edition, and Director Donald Bear wrote a series of articles for the News-Press that elaborated on the themes, content, and broader significance of the exhibition. Three paintings from this exhibition became part of the permanent collection of the SBMA: Henry Mattson’s (1873–1953) Night Mystery, Max Weber’s (1881–1961) Winter Twilight, and Katherine Schmidt’s (1899–1978) Pear in Paper Bag (scrapbook 1941–1944–10). The theme of this exhibition was suggested by Mrs. Spreckels (Emily Hall Spreckels (Tremaine)) at a Board meeting and was unanimously approved. The title of the exhibition was suggested by Donald Bear, also unanimously approved by the Board. Van Gogh Paintings (September 9) Seventeen of Vincent van Gogh’s (1853–1890) paintings were shown in this exhibition of the “most tragic painter in history.” This exhibition was shown in conjunction with the Master Impressionists show (see “Three Master French Impressionists” below).