Role-Playing Methods in the Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Splash Pad Opens in Lynn Haven

DEATH TOLL RISES IN INDONESIAN EARTHQUAKE | A10 PANAMA CITY LOCAL | B1 FISHERMAN CATCHES MASSIVE 330-POUND WARSAW GROUPER Tuesday, October 2, 2018 www.newsherald.com @The_News_Herald facebook.com/panamacitynewsherald 75¢ Search for Second splash pad missing woman continues opens in Lynn Haven Mayor Family asks aid in the Margo for help, fears search, Anderson ‘kidnapping’ Meither has stands under not been a bucket of By Zack McDonald seen since. water with 747-5071 | @PCNHzack | Sev- children. The [email protected] Meither eral family Leon Miller members Splash Pad PANAMA CITY BEACH have now taken to social offi cially — Days after a Kentucky media in hopes of receiving opened on woman disappeared while help from the public. Monday at on the beach, her family “She has six grandchil- Cain-Griffi n continues its pleas for the dren – she is their every Park in Lynn public’s help in locating thing and they are all Haven. [PATTI her. heartbroken,” said Mike BLAKE/THE Nancy Meither, 66, of Meither, Nancy’s youngest NEWS HERALD] Dry Ridge, Kentucky, was son. “We need to find her. last seen Friday at about 10 She is my everything and p.m. beach side. She was my family’s everything… last seen wearing a black We need answers please.” and gray one-piece swim- Mike Meither said he suit behind the Sunbird wasn’t in Panama City Condominiums, 9850 S Beach at the time but has Thomas Drive, where her since driven down to join husband had left her to go to the search. He said he hopes their room. -

Pizzas $ 99 5Each (Additional Toppings $1.40 Each)

AJW Landscaping • 910-271-3777 August 18 - 24, 2018 Mowing – Edging – Pruning – Mulching FREE Estimates – Licensed – Insured – Local References Fiercely MANAGEr’s SPECIAL funny females 2 MEDIUM 2-TOPPING Pizzas $ 99 5EACH (Additional toppings $1.40 each) 1352 E Broad Ave. 1227 S Main St. Issa Rae and Yvonne Orji as Rockingham, NC 28379 Laurinburg, NC 28352 seen in “Insecure” (910) 997-5696 (910) 276-6565 *Not valid with any other offers Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street Laurinburg, NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, August 18, 2018 — Laurinburg Exchange Third time’s the charm: HBO comedy ‘Insecure’ is back for season 3 By Kyla Brewer a tight-knit group of black wom- She’s directed a number of epi- TV Media en, who are often underrepre- sodes of “Insecure,” and her in- sented in prime-time television. volvement led to Knowles becom- s young women navigate the This season, the women strive to ing the show’s music consultant. Aups and downs of modern make the right decisions as they Music is a big part of the series. life, it helps to have a crew of continue to evolve in their 30s. In Featuring indie acts and estab- steadfast girlfriends along for the an interview with the Hollywood lished artists, the show’s sound- ride. Reporter, Rae talked about how track has earned praise from crit- Issa Dee (Issa Rae, “The Misad- the characters grow in season 3. ics and fans, who can’t get ventures of Awkward Black Girl”) “This season is about not act- enough of Rae’s raps in front of relies on her close friends in an- ing like you’re naive anymore or her mirror. -

Think Christian – a Theology of the Office

A Theology of the office 8½ x 11 in 20 lb Text 21.5 x 27.9 cm 75 GSM Bright White 92 Brightness 500 Sheets 30% Post-Consumer Recycled Fiber RFM 20190610 TC TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction by JOSH LARSEN 1 The Awkward Promise of The Office by JR. FORASTEROS 3 Can Anything Good Come Out of Scranton? by BETHANY KEELEY-JONKER 6 St. Bernard and the God of Second Chances by AARIK DANIELSEN 8 The Irrepressible Joy of Kelly Kapoor by KATHRYN FREEMAN 11 Let Scott’s Tots Come Unto Me by JOE GEORGE 13 The Office is Us by JOSH HERRING 16 Editors JOSH LARSEN & ROBIN BASSELIN Design & Layout SCHUYLER ROOZEBOOM Introduction by JOSH LARSEN You know the look. Someone (usually Michael) says something cringeworthy and someone else (most often Jim) glances at the camera, slightly widens his eyes, and imperceptibly grimaces. That was weird, his face says, for all of us. That look was the central gag of The Office, NBC’s reimagining of a British television sitcom about life amidst corporate inanity. The joke never got old over nine seasons. Part of the show’s conceit is that a documentary camera crew is on hand capturing all this footage, allowing the characters to break the fourth wall with a running, reaction-shot commentary. A textbook example can be found in “Koi Pond,” from Season 6, when Jim (John Krasinski) finds the camera after Michael (Steve Carell) makes yet another inappropriate analogy during corporate sensitivity training. Don’t even try to count the number of times throughout The Office that eyebrows are alarmingly raised. -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064. -

Template 734..773

Journal of the Senate Number 21—Regular Session Monday, March 7, 2016 CONTENTS Senate in the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag of the United States of America. Address by President . .748 Bills on Third Reading . 734, 749 BILLS ON THIRD READING Call to Order . 734, 742 Co-Introducers . .773 CS for CS for SB 7000—A bill to be entitled An act relating to growth management; amending s. 163.3184, F.S.; clarifying statutory House Messages, Final Action . 773 language; amending s. 380.06, F.S.; providing that a proposed devel- House Messages, First Reading . 768 opment that is consistent with certain comprehensive plans is not re- Motions . 742, 767 quired to undergo review pursuant to the state coordinated review Recognition of President . 742 process; providing applicability; providing an effective date. Remarks . 742 —was read the third time by title. Reports of Committees . .768 Senate Pages . 773 On motion by Senator Simpson, CS for CS for SB 7000 was passed Special Guests . 742 and certified to the House. The vote on passage was: Special Presentation . 747, 748 Unveiling of Portrait . 747 Yeas—32 Vote Preference . 734, 735, 736, 737, 738, 739, 740, 741, 750, 751, 765 Mr. President Diaz de la Portilla Margolis Abruzzo Evers Montford CALL TO ORDER Altman Gaetz Negron Bean Galvano Richter The Senate was called to order by President Gardiner at 10:00 a.m. A quorum present—33: Benacquisto Gibson Ring Bradley Grimsley Simmons Mr. President Diaz de la Portilla Margolis Brandes Hays Simpson Abruzzo Evers Montford Bullard Hukill Soto Altman Gaetz -

How Do Bishops Decide When to Speak? an Exclusive Excerpt from a New Report

NOVEMBER 26, 2018 THE JESUIT REVIEW OF FAITH AND CULTURE 2018 CPA MAGAZINE OF THE YEAR How Do Bishops Decide When to Speak? An exclusive excerpt from a new report p20 #ChurchToo: A Story Finding God in a of Clergy Misconduct Newsroom Shooting p28 p34 The Evolution of René Girard p40 CHRISTMAS GIFTS These gifts are for Faith, Comfort, & Joy Read together and share stories of faith this Christmas. 20% off for a limited time!* Using simple yet profound truths, this book helps children quiet their minds and listen to their hearts to know that we are all deeply loved by God. Visit www.GodIsintheSilence.com for fun activities to do at home. English | PB | 978-0-8294-4657-9 | $8.95 $7.16 Bilingual | PB | 978-0-8294-4696-8 | $8.95 $7.16 Leo’s a shy, six-year-old boy who overcomes his self-doubt and discovers that he has a beautiful gift to share with the world – just in time for Christmas! Visit www.LeosGift.com for fun activities to do at home. Hardcover | 978-0-8294-4600-5 | $19.95 $15.96 This vibrantly illustrated book will help children appreciate the symbols of faith all around us, especially those we see during the seasons of Advent and Christmas. Each symbol includes a description for younger readers, as well as a more detailed explanation to appeal to a wide range of ages. Hardcover | 978-0-8294-4651-7 | $19.95 $15.96 *Use promo code 4905 to receive 20% off these select items. Shipping and handling are additional. -

Thesis – Dissertation Example

A Good Example of a Christian Counseling Thesis / Dissertation for the MA / MCC / DCC / Th.D. Programs MASTER’S THESIS 25 CASE STUDIES October 6, 2006 Table of Contents Case Study Page Number CASE STUDY ON ABANDOMENT 1 CASE STUDY ON ALCOHOLISM……………………………………………………..5 CASE STUDY ON ANGER …………………………………………………………...10 CASE STUDY ON ANGER …………………………………………………………...14 CASE STUDY ON BITTERNESS …………………………………………………….19 CASE STUDY ON DEPRESSION …………………………………………………….24 CASE STUDY ON DEPRESSION …………………………………………………….30 CASE STUDY ON ANXIETY …………..……………………………………………35 CASE STUDY ON FEAR ……………………………………………………………...41 CASE STUDY ON GRIEF ……………………………………………………………..47 CASE STUDY ON GRIEF AND LOSS ……………………………………………….51 CASE STUDY ON GRIEVING TEEN ………………………………………………...56 CASE STUDY ON LIVING WITH DEFORMITY ……………………………………61 CASE STUDY ON MARITAL CONFLICT …………………………………………...66 CASE STUDY ON MARRIAGE BURNOUT …………………………………………72 CASE STUDY ON NONSEXUAL ABUSE …………………………………………...78 CASE STUDY ON OCCULTISM ……………………………………………………..83 CASE STUDY ON PEER REJECTION ……………………………………………….87 CASE STUDY ON POST-ABORTION ……………………………………………….92 CASE STUDY ON SEXUAL ABUSE ………………………………………………...97 CASE STUDY ON STRESS ………………………………………………………….102 CASE STUDY ON SUFFERING SANGUINE ………………………………………106 CASE STUDY ON SUSPECTED ADHD ……………………………………………111 CASE STUDY ON THE DYING PROCESS ………………………………………...118 CASE STUDY ON UNPLANNED PREGNANCY ………………………………….122 CASE STUDY ON ABANDONMENT Personal Background Information Name: Regina Sex: Female Age: 32 Martial Status: Separated Children: 1 girl Reason For Seeking Counseling 1. Abandonment of husband as he no longer wanted to be married 2. She learned she had cancer two months before her husband walked out Overview Her A.P.S. report indicated that she was: 1. Phlegmatic Choleric in Inclusion 2. Phlegmatic Supine in Control 3. Supine in Affection Session Notes: Session One: Regina came to my office as she was seeking Christian based counseling and began by pouring out all of her problems with out hardly a pause. -

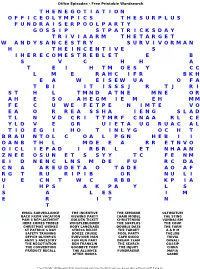

T H E N E G O T I a T I O N O F F I C E O L Y M P I C S T H E S U R P L U S F U N D R a I S E R P O O L P a R T Y G O S S I

Office Episodes - Free Printable Wordsearch THENEGOTIATION OFFICEOLYMPICS THESURPLUS FUNDRAISERPOOLPARTY GOSSIPSTP ATRICKSDAY TRIVIAARMTHETA RGET WANDYSANCESTRY SURVIVORMAN HTHEI NCENTIVES IHERECOMESTREBLET EB SV CHH A TEI HTMOESY CC LME RAHCIFR BKH EAWEI SEWUAO FA TBIIT ISSSJRTJ RI STHL TMNDATNEMNE OR AHESO AHEGMIEMEH MM FECUWE FETPENIMTE VO EAORREA SSHAIENG SLAD TLNVDCR ITTMRFCNAA RLCE YLDVEGR UIETAUGRUACA L TIOEGIHO TINLYGOC HT BRAUNTOLCOA LPGNHEBI I OANBTHL MDEEARR ETNVO OICLIEFADI RBRLET NHAAN ZNEEOSUNETS SYYTC FENM EIDNENCLNS MDEFU RCDA CNAAREUDETA OTADE AOAF RGTRURI PIBOR NULI UECNT WCRBB KPIA IHPS AKPAY LS SA LES IM ER IT N T EMAIL SURVEILLANCE THE INCENTIVE THE SEMINAR ULTIMATUM BACK FROM VACATION VIEWING PARTY CHAIR MODEL THE STING PAM S REPLACEMENT GOLDEN TICKET CHRISTENING VANDALISM HERE COMES TREBLE WHISTLEBLOWER THE SURPLUS THE COUP CHRISTMAS WISHES BODY LANGUAGE DOUBLE DATE THE FARM ST PATRICK S DAY STRESS RELIEF THE TARGET AARM SAFETY TRAINING BOOZE CRUISE POOL PARTY THE JOB OFFICE OLYMPICS SURVIVOR MAN CAFE DISCO TRIVIA ANDY S ANCESTRY FUN RUN PART DREAM TEAM DIWALI THE NEGOTIATION BEN FRANKLIN THE SEARCH GOSSIP THE CONVENTION GOODBYE TOBY THE INJURY CHINA PRODUCT RECALL THE ALLIANCE FUNDRAISER MAFIA AFTER HOURS SABRE Free Printable Wordsearch from LogicLovely.com. Use freely for any use, please give a link or credit if you do. Office Episodes - Free Printable Wordsearch ACNIGHT OUTPROMOS SP NAT AM GSHTHEDELIVE RY MU RIET DTEH YNDGH ESVCS AOUEESUITWARE HOUSEXIIETS T NNETD ERRHNON DILTE THEBOATMSHDTUAL U YGYP ACDHTNTO -

Fiercely Funny Females

Alignment Services August 18 - 24, 2018 for Passenger, Light Truck, & Heavy Duty Monday - Friday 8am - 5pm 517 Warsaw Road Fiercely Clinton, North Carolina 28328 Email: [email protected] Michael Edwards Ph:910-490-1292 • Fax 910-490-1286 funny Owner Our Seafood is females Off the Hook! Best Hush Puppies ...............................1st Best Seafood .........................(tied for) 1st Best Cole Slaw ................................... 2nd Best Restaurant for Lunch ................... 3rd See our specials on page 8. 125 Southeast Blvd Clinton, NC 910-490-1321 Issa Rae and Yvonne Orji as seen in “Insecure” Open Mon-Sat 11am to 9:30pm Sunday 11am to 5pm Page 2 — Saturday, August 18, 2018 — Sampson Independent Third time’s the charm: HBO comedy ‘Insecure’ is back for season 3 By Kyla Brewer sions as they continue to evolve in Rae revealed one of this season’s TV Media their 30s. In an interview with the major themes. Hollywood Reporter, Rae talked “I love black masculinity as it re- s young women navigate the about how the characters grow in lates to black women,” Rae said. “I Aups and downs of modern life, it season 3. think that’s something interesting helps to have a crew of steadfast “This season is about not acting that we haven’t gotten a chance to girlfriends along for the ride. like you’re naive anymore or that explore yet — and specifically toxic Issa Dee (Issa Rae, “The Misad- you don’t know better,” Rae ex- male black masculinity as it relates ventures of Awkward Black Girl”) plained. “So it is about, what does it to black women. -

The Sounding Board, Fall 2020

FALL 2020 The Sounding Board The Publication of the National Federation of the Blind of New Jersey IN THIS ISSUE LINDA MELENDEZ Provides an Update on Access Link Services SERENA CUCCO Shares the Story of a Life that Inspired Confidence MELISSA LOMAX Reflects on Mentoring Difficult Students JONATHAN ZOBEK Reveals How his Cooking Skills Improved during COVID-19 CARLEY MULLIN Describes the Louisiana Tech Training Live the Life You Want Fall 2020 The Sounding Board 2 THE SOUNDING BOARD Fall 2020 Katherine Gabry, Editor Co-Editors: Annemarie Cooke, Mark Gasaway, Jerilyn Higgins & Mary Jo Partyka Published by e-mail and on the Web through Newsline by The National Federation of the Blind of New Jersey www.nfbnj.org Joseph Ruffalo, President State Affiliate Office 254 Spruce Street Bloomfield, NJ 07003 Email: [email protected] Articles for future editions should be submitted to the State Affiliate Office at [email protected] Advertising rates are $25 for a half page and $40 for a full page. Ads for future editions should be sent to [email protected] The editorial staff reserves the right to edit all articles and advertising for space and/or clarity considerations. Donations should be made payable to the National Federation of the Blind of New Jersey and sent to the State Affiliate office. To subscribe via Newsline, contact Jane Degenshein 973-736-5785 or [email protected] DREAM MAKERS CIRCLE You can help build a future of opportunity for the blind by becoming a member of our Dream Makers Circle. It is easier than you think. You can visit your bank and convert an account to a P.O.D. -

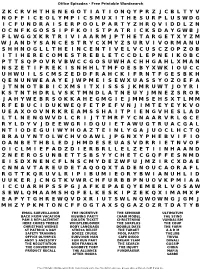

Z K C R V H T H E N E G O T I a T I O N Q Y P R Z J C B L T Y V N O F F I C E O L Y M P I C S M U X I T H E S U R P L U S W

Office Episodes - Free Printable Wordsearch ZKCRVHTHENEGOTIATIO NQYPRZJCBLTYV NOFFICEOLYMPICSMUXI THESURPLUSWDG ICFUNDRAISERPOOLPAR TYZHRQVIDDLZN OCNFKGOSSIPFKOISTPA TRICKSDAYGWBJ FLWGGXKRTRIVIAARMJP THETARGETXYZM WJANDYSANCESTRYCXMYZ SURVIVORMANU SHHNOGLLTHEINCENTIV ELVCUSCZOPZOB ITIHERECOMESTREBLET CCDLEPNEIKOBC PTTSQPOVRVBWCCGOSUWHAC HHGAHLXMAN NSZETIFREKISNHHLTMF OESBYXWKIOUCC UHWUILSCMSZEDDFRAHCK IFRNTFGESBKH QENUNWEAAYEJWPMEISEWX UASSYOZOEFA JTNNOTBBICXMSITXIS SSJKMRUWTJOYRI KSTNTHDRLVSKTMNDLATN EUYJMNEZSROR JAHYWEBRSOKKAHEGMGIE JMMSEHSXTLMM RFEBUCIDUKWEQFETPEFV NJIMTEYEYKVO UEAXOOVNRKREAMSSHAIT PIENGVHESLAD LTLNENGWVDLCRIJTTMR FYCNAARVRLGCE RYLDYVJDEEWGRIDQUIE TAWUGTRUACGAL NTIODEGUIWYHOAZTEIN LYGAJUOCLHCTQ BRAUYNTOLWCHVOAWLJPGN XYPHEBVIFIO OANBETHBLEDJHMDESEUA SVDRRIETNVOF OICLMIEFADZDIERBRL LELZETIINHAAND ZNEEROSUNBETTSBSYYCH ETCGQFFESNMD EISDXNENCFLNSCMYDEZW FUJMZIRCXDAE CNNAVTAREUDETAQOQXTAD ENOUCAORAFL RGTTKQRUVLRIPIBUMI EORYBWIANUHLID UUKERJCNGTKVWRCHFURBB PNUOVKPMIAA ICCUARHPSSPGJAFKEPA EQYEMERLVOSAW SEWLQMAAMSHQFELKESKIP ZEKQXIMAMXP EAPYTGHREWQVDXRIUTSWL NQWOWNGJGMJ MHZYPKMTONCFFOGTAXSQG AZOZRTDATYB EMAIL SURVEILLANCE THE INCENTIVE THE SEMINAR ULTIMATUM BACK FROM VACATION VIEWING PARTY CHAIR MODEL THE STING PAM S REPLACEMENT GOLDEN TICKET CHRISTENING VANDALISM HERE COMES TREBLE WHISTLEBLOWER THE SURPLUS THE COUP CHRISTMAS WISHES BODY LANGUAGE DOUBLE DATE THE FARM ST PATRICK S DAY STRESS RELIEF THE TARGET AARM SAFETY TRAINING BOOZE CRUISE POOL PARTY THE JOB OFFICE OLYMPICS SURVIVOR MAN CAFE DISCO TRIVIA ANDY S ANCESTRY FUN -

Pilot Earth Skills Earth Kills Murphy's Law Twilight's Last Gleaming His Sister's Keeper Contents Under Pressure Day Trip Unity

Pilot Earth Skills Earth Kills Murphy's Law Twilight's Last Gleaming His Sister's Keeper Contents Under Pressure Day Trip Unity Day I Am Become Death The Calm We Are Grounders Pilot Murmurations The Dead Don't Stay Dead Hero Complex A Crowd Of Demons Diabolic Downward Spiral What Ever Happened To Baby Jane Hypnos The Comfort Of Death Sins Of The Fathers The Elysian Fields Lazarus Pilot The New And Improved Carl Morrissey Becoming Trial By Fire White Light Wake-Up Call Voices Carry Weight Of The World Suffer The Children As Fate Would Have It Life Interrupted Carrier Rebirth Hidden Lockdown The Fifth Page Mommy's Bosses The New World Being Tom Baldwin Gone Graduation Day The Home Front Blink The Ballad Of Kevin And Tess The Starzl Mutation The Gospel According To Collier Terrible Swift Sword Fifty-Fifty The Wrath Of Graham Fear Itself Audrey Parker's Come And Gone The Truth And Nothing But The Truth Try The Pie The Marked Till We Have Built Jerusalem No Exit Daddy's Little Girl One Of Us Ghost In The Machine Tiny Machines The Great Leap Forward Now Is Not The End Bridge And Tunnel Time And Tide The Blitzkrieg Button The Iron Ceiling A Sin To Err Snafu Valediction The Lady In The Lake A View In The Dark Better Angels Smoke And Mirrors The Atomic Job Life Of The Party Monsters The Edge Of Mystery A Little Song And Dance Hollywood Ending Assembling A Universe Pilot 0-8-4 The Asset Eye Spy Girl In The Flower Dress FZZT The Hub The Well Repairs The Bridge The Magical Place Seeds TRACKS TAHITI Yes Men End Of The Beginning Turn, Turn, Turn Providence The Only Light In The Darkness Nothing Personal Ragtag Beginning Of The End Shadows Heavy Is The Head Making Friends And Influencing People Face My Enemy A Hen In The Wolf House A Fractured House The Writing On The Wall The Things We Bury Ye Who Enter Here What They Become Aftershocks Who You Really Are One Of Us Love In The Time Of Hydra One Door Closes Afterlife Melinda Frenemy Of My Enemy The Dirty Half Dozen Scars SOS Laws Of Nature Purpose In The Machine A Wanted (Inhu)man Devils You Know 4,722 Hours Among Us Hide..