2. Stratification and Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bang on a Can Announces Onebeat Marathon #2 Live Online! Sunday, May 2, 2021 from 12PM - 4PM EDT

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press contact: Maggie Stapleton, Jensen Artists 646.536.7864 x2, [email protected] Bang on a Can Announces OneBeat Marathon #2 Live Online! Sunday, May 2, 2021 from 12PM - 4PM EDT A Global Music Celebration curated and hosted by Found Sound Nation. Four Hours of LIVE Music at live.bangonacan.org Note: An embed code for the OneBeat Marathon livestream will be available to press upon request, to allow for hosting the livestream on your site. The OneBeat Virtual Marathon is back! OneBeat, a singular global music exchange led by our Found Sound Nation team, employs collaborative original music as a potent new form of cultural diplomacy. We are thrilled to present this second virtual event, showcasing creative musicians who come together to make music, not war. The OneBeat Marathon brings together disparate musical communities, offering virtuosic creators a space to share their work. These spectacular musicians join us from across the globe, from a wide range of musical traditions. They illuminate our world, open our ears, and break through the barriers that keep us apart. - Julia Wolfe, Bang on a Can co-founder and co-artistic director Brooklyn, NY — Bang on a Can is excited to present the second OneBeat Marathon – Live Online – on Sunday, May 2, 2021 from 12PM - 4PM ET, curated by Found Sound Nation, its social practice and global collaboration wing. Over four hours the OneBeat Marathon will share the power of music and tap into the most urgent and essential sounds of our time. From the Kyrgyz three-stringed komuz played on the high steppe, to the tranceful marimba de chonta of Colombia's pacific shore, to the Algerian Amazigh highlands and to the trippy organic beats of Bombay’s underground scene – OneBeat finds a unifying possibility of sound that ties us all together. -

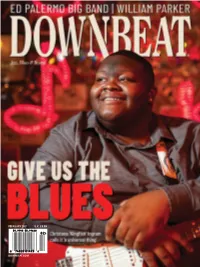

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Squeezeboxnew Directions in Music

NEW DIRECTIONS IN MUSIC SQUEEZEBOXNEW DIRECTIONS IN MUSIC NEW DIRECTIONS IN MUSIC ARTISTIC DIRECTOR’S WELCOME It was the accordion in Kurt Weill’s The Threepenny Opera that hooked me on this chameleon of an instrument. Its very sound conjures up such an aching nostalgia—bittersweet and decadent—that one could feel and smell the Berlin cabarets. It simply gets under your skin. From giddy hysteria to the depths of depression, the accordion family plumbs the full spectrum of human emotion. An instrument that is at home on the street corner as well as in the concert hall, it occupies a unique place in cultures around the globe. Two extraordinary Canadian pioneers, Joseph Macerollo and Joseph Petric, lifted the accordion from novelty status to full-fledged concert instrument, contributing to the creation and performance of new works on a monumental scale. We are delighted to have Joseph Macerollo and his protégé Michael Bridge with us tonight, playing definitive Canadian works by R. Murray Schafer, Alexina Louie, and Marjan Mozetich. The accordion developed in Europe in the 1770s, a descendent of the Chinese sheng, but powered by bellows instead of the breath. Virtuoso performer gamin’s instrument, the Korean saenghwang, is also descended from the sheng. She performs Korean composer Taejong Park and a world premiere by Canadian Anna Pidgorna. The bandoneón, used in popular and religious music, evolved in the 1880s and was brought to Argentina in the 20th century. There, Proud to support SoundMakers. in the streets, it gave birth to the sensational tango and milonga genres, performed tonight in a return visit by legendary Argentinian bandoneón player Héctor del Curto. -

Coexistence of Classical Music and Gugak in Korean Culture1

International Journal of Korean Humanities and Social Sciences Vol. 5/2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14746/kr.2019.05.05 COEXISTENCE OF CLASSICAL MUSIC AND GUGAK IN KOREAN CULTURE1 SO HYUN PARK, M.A. Conservatory Orchestra Instructor, Korean Bible University (한국성서대학교) Nowon-gu, Seoul, South Korea [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7848-2674 Abstract: Classical music and Korean traditional music ‘Gugak’ in Korean culture try various ways such as creating new music and culture through mutual interchange and fusion for coexistence. The purpose of this study is to investigate the present status of Classical music in Korea that has not been 200 years old during the flowering period and the Japanese colonial period, and the classification of Korean traditional music and musical instruments, and to examine the preservation and succession of traditional Gugak, new 1 This study is based on the presentation of the 6th international Conference on Korean Humanities and Social Sciences, which is a separate session of The 1st Asian Congress, co-organized by Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland and King Sejong Institute from July 13th to 15th in 2018. So Hyun PARK: Coexistence of Classical Music and Gugak… Korean traditional music and fusion Korean traditional music. Finally, it is exemplified that Gugak and Classical music can converge and coexist in various collaborations based on the institutional help of the nation. In conclusion, Classical music and Korean traditional music try to create synergy between them in Korean culture by making various efforts such as new attempts and conservation. Key words: Korean Traditional Music; Gugak; Classical Music; Culture Coexistence. -

(EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli

FAMILY (EN) GROUP (EN) KEYWORD (EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli Wind Accordions Accordion Strings Zithers Accord‐zither Percussion Drums Adufe Strings Musical bows Adungu Strings Zithers Aeolian harp Keyboard Organs Aeolian organ Wind Others Aerophone Percussion Bells Agogo Ogebe ; Ugebe Percussion Drums Agual Agwal Wind Trumpets Agwara Wind Oboes Alboka Albogon ; Albogue Wind Oboes Algaita Wind Flutes Algoja Algoza Wind Trumpets Alphorn Alpenhorn Wind Saxhorns Althorn Wind Saxhorns Alto bugle Wind Clarinets Alto clarinet Wind Oboes Alto crumhorn Wind Bassoons Alto dulcian Wind Bassoons Alto fagotto Wind Flugelhorns Alto flugelhorn Tenor horn Wind Flutes Alto flute Wind Saxhorns Alto horn Wind Bugles Alto keyed bugle Wind Ophicleides Alto ophicleide Wind Oboes Alto rothophone Wind Saxhorns Alto saxhorn Wind Saxophones Alto saxophone Wind Tubas Alto saxotromba Wind Oboes Alto shawm Wind Trombones Alto trombone Wind Trumpets Amakondere Percussion Bells Ambassa Wind Flutes Anata Tarca ; Tarka ; Taruma ; Turum Strings Lutes Angel lute Angelica Percussion Rattles Angklung Mechanical Mechanical Antiphonel Wind Saxhorns Antoniophone Percussion Metallophones / Steeldrums Anvil Percussion Rattles Anzona Percussion Bells Aporo Strings Zithers Appalchian dulcimer Strings Citterns Arch harp‐lute Strings Harps Arched harp Strings Citterns Archcittern Strings Lutes Archlute Strings Harps Ardin Wind Clarinets Arghul Argul ; Arghoul Strings Zithers Armandine Strings Zithers Arpanetta Strings Violoncellos Arpeggione Keyboard -

THE FUSION of KOREAN and WESTERN ELEMENTS in ISANG YUN's KONZERT FÜR FLÖTE UND KLEINES ORCHESTER by SONIA CHOY (Under

THE FUSION OF KOREAN AND WESTERN ELEMENTS IN ISANG YUN’S KONZERT FÜR FLÖTE UND KLEINES ORCHESTER by SONIA CHOY (Under the Direction of Angela Jones-Reus and Stephen Valdez) ABSTRACT The Korean born composer, Isang Yun (1917-1995) is renowned for his synthesis of traditional Korean music and Taoist philosophy with Western compositional techniques. Yun adapted the Eastern concept of a single tone as the basis of a work into Western music. Yun’s early works (1959-1975) are based on the twelve tone system, while the compositions in his later periods (1975-1992) use a simplified musical language based on Eastern sounds. Yun’s Konzert für Flöte und Kleines Orchester (Concerto for Flute and Small Orchestra, 1977) features this language. The Konzert is influenced by three elements: first, the sound and performance techniques of traditional Korean wind instruments including the daegum, the danso, and the piri; second, Taoism, particularly in the way the work evokes a pervasive dialectic of Yin and Yang; and third, a programmatic fantasy influenced by two Korean poems, the anonymous Chungsanboelkok (Poem of a Clear Mountain) and Seok-cho Sin’s related poem, Chungsana, Malhayeora (Speak, the Clear Mountain). Focusing on the intersection of these three elements, this document explores the flute concerto in detail. It includes an overview of Yun’s stylistic influences, in particular the Korean instruments and performance practice he evokes in the work. It also describes the short period in which Yun composed his thirteen concertos (1976-1992), the musical style of which reflects his experience of abduction and imprisonment as well as his broader political and social concerns. -

Coreanas MUNDIAL Estas Estatuillas De Gres Datan De Los Siglos V-VI De Nuestra Era (Época Antigua De Silla)

Una ventana El C]orT*Pf) ^e ^a unesco abierta al mundo S? ¿?- ¡Í£aúd££i». Hi TESOROS DEL ARTE Figurillas coreanas MUNDIAL Estas estatuillas de gres datan de los siglos V-VI de nuestra era (época antigua de Silla). Aunque a menudo de factura rudimentaria, este tipo de figurillas no carecen de expresividad, mostrando incluso un sentido agudo de la observación y un alegre humorismo. En la foto, un hombre (8,5 cm de altura) y una mujer (5.3) obra de los antiguos alfareros escultores coreanos, que mostraban no menor talento en la República reproducción de animales de todas clases (reptiles, perros, vacas, tigres, pájaros, conejos, etc.) de Corea Foto © Kim Tae-byok, Seúl ei Correo ^e *a unesc° páginas 4 CORRIENTES ESPIRITUALES EN LA COREA TRADICIONAL por Chang Byung-kil DICIEMBRE 1978 AÑO XXXI 11 200 AÑOS ANTES DE GUTENBERG, PUBLICADO EN 19 IDIOMAS LOS VERDADEROS INVENTORES DE LA TIPOGRAFÍA por Chon Hye-bong Español Italiano Turco Hindi Urdu Inglés 13 UN ALFABETO QUE RETRATA LA VOZ HUMANA Francés Tamul Catalán por Lee Ki-mun Ruso Hebreo Malayo Alemán . Persa Coreano 14 "EL CANTO DE LA TIERRA" Arabe Portugués (Fotos) Japonés Neerlandés 16 UN FRESCO ANIMADO DE LA VIDA COTIDIANA 19 UN APORTE ORIGINAL A LA PINTURA ORIENTAL Publicación mensual de la UNESCO por Choe Sun-u (Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura) 22 UN ARTE VIVIENTE QUE VUELVE DE ULTRATUMBA Venta y distribución : por Kim Won-yong Unesco, place de Fontenoy, 75700 París Tarifas de suscripción : 31 LOS MAESTROS CERAMISTAS DE COREA un año : 35 francos (España : 750 pesetas) dos años : 58 francos. -

The Far East

1 Gallery Guide St. Louis, A Musical Gateway: THE FAR EAST Asia, the world’s largest continent on earth, is surrounded by the Pacific, Arctic, and Indian Oceans. Featured in Rooms 1 & 2 of the display are musical instruments from the East Asia geographical region. This region shows the musical intersections influenced by travel and trade among the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, Mongolia, Japan, Tibet, and South and North Korea. This exhibit is the third in a series that celebrates St. Louis’ multicultural heritage communities. It features rare and beautiful instruments of the Far East and Oceania drawn from the Hartenberger World Music Collection of Historical Instruments Dr. Aurelia & Jeff Hartenberger, Karrie Bopp, Dr. Jaclyn Hartenberger and Kevin Hartenberger. 2 The Far East The musical traditions of the Far East serve to demonstrate important aspects of the social, spiritual, and aesthetic values of their cultures of origin. These traditions have also been shaped over centuries, as people traveled by land and sea along trade routes spanning vast territories. Merchants and travelers exchanged silk and spices as well as languages, ideas, music, and musical instruments. By the eleventh (11th) century musical instruments from the Middle East and Central Asia could be found both in Europe and in parts of East, South, and Southeast Asia. In ancient China, musical instruments were divided into "eight sounds" — based on the materials used in their construction: Metal (jin), stone (shi), silk (si), bamboo (zhu), gourd (pao), clay (tao), leather (ge) and wood (mu). Today, instruments associated with this early classification system are reconstructed for use in ensembles that perform in museums and historical buildings. -

Enculturation of Kledi Dayak Kebahan Penyelopat (Inheritance

Enculturation of Kledi Dayak kebahan Penyelopat (Inheritance, Organology Study, and playing techniques of Traditional Musical Instrumentin remote area of West Kalimantan) Imam Ghozali Lecturer in Performing Arts Education Study Program FKIP University Tanjungpura Pontianak. ([email protected]) ABSTRACT The background of this study is Kledi's conservation problems, musical instruments that have local wisdom values are still traditionally preserved in West Kalimantan. Kledi is the production of local culture tradition of the people especially in Engkurai areawhich has been very difficult to find. Therefore it is necessary to maintain and develop it. Thus it is necessary to do assessmentofthe musical instrument through this research. The study used qualitative methods with interpretive analytic descriptive research.The data collected are in the form of matters relating to inheritance pattern, the way of making, basic materials, and the technique for playing Kledi's musical instrument. Data collection technique use technical observation, interview, and document study. Test of the validity in the data is done through in-depth interview and triangulation of source also technique. Based on data processing result and analysiswhich have been done, it can be concluded that organologically Kledi traditional musical instrument isinflatable devicemusical instrument typically of Dayak Kebahan Penyelopatpeople, because all the constituent elements of the tool are found in nature and in typical of local areasuch as reed, pumpkin, apin, and gum klulut. Technique of Traditional Musical Instrument ofDayak Kebahan Penyelopat generally has the same technique with other inflatable device, specifically it can be played homophone, added with one distinctive tone of traditional musical instrument that ise tone. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Chong, Kee Yong Multi-layered ethnic and cultural influences in my musical compositions Original Citation Chong, Kee Yong (2016) Multi-layered ethnic and cultural influences in my musical compositions. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/31091/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ MULTI-LAYERED ETHNIC AND CULTURAL INFLUENCES IN MY MUSICAL COMPOSITIONS KEE YONG CHONG A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Huddersfield CeReNeM, Centre for Research in New Music July 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Copyright statement --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 Acknowledgements ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Abstract ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 Chapter I. Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1. -

Test 7: Final Crossword - Chinese Musical Instruments

10 Test 7: Final Crossword - Chinese Musical Instruments 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Across: Down: 2 The English word for SHENG 1 Chinese seven-stringed-zither 5 One categorie of the ancient Chinese system 3 Dynasty in China with rich development of cultural for musical instruments (stringed instruments) forms of expression, music instruments and 7 Metal gong with a sound bending upwards ensembles 8 Other name of the flower-drum 4 Province in China, where the first BIAN ZHONG was found in a tomb 9 Shape of the YUE QIN 6 Stone chime instruments 10 The contrabass instrument in a Chinese 9 Wooden fish in front of Chinese Buddhist temples or orchestra on the left side of the altar 12 Racket with a big bell at the right side of the 11 Main material of Chines flute instruments entrance of Chinese Buddhist temples 13 The animal, which gives the skin for the ER HU 9 Test 6: Mixed Questions: Chinese Idiophones and Membranophones 1. In which Chinese province did researchers find the eldest Chinese membranophone? a) Yunnan b) Henan c) Anhui 2. Which type of LION DANCE DRUM can you identify in the PowerPointPresentation? a) The "southern" type b) The "northern" type c) The "eastern" type 3. Stone-chimes played in ancient China were played during... a) banquets b) ceremonies c) temple services d) birthdays 4. The BIAN ZHONG originates from the following dynasty: a) HAN b) ZHOU c) MING d) SHANG 5. How many octaves can we find in the BIAN ZHONG? a) six b) three c) five d) four 6. -

Metropolis New Music Festival 2018

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra & Melbourne Recital Centre present Metropolis New Music Festival 2018 19 & 21 APRIL 2018 CONCERT PROGRAM Presented in association with Melbourne Recital Centre and Monash University, the MSO’s Metropolis New Music Festival Education Partner. MEET THE ARTISTS METROPOLIS 1 THURSDAY 19 APRIL Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Clark Rundell conductor Wu Wei sheng Australian String Quartet Ligeti String Quartet No.1 Métamorphoses nocturnes Chin Šu – Australian premiere MELBOURNE SYMPHONY UNSUK CHIN ORCHESTRA COMPOSER INTERVAL Established in 1906, the Melbourne Unsuk Chin’s music has been performed by Vincent Hood Yourself In Stars – world premiere Symphony Orchestra (MSO) is an arts ensembles such as the Berlin Philharmonic, Chin ParaMetaString leader and Australia’s longest-running Boston Symphony, Deutsches professional orchestra. Chief Conductor Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Ensemble Sir Andrew Davis has been at the helm intercontemporain, Kronos Quartet, ___ of MSO since 2013. Engaging more than Hilliard Ensemble, and Klangforum Wien, 3 million people each year, the MSO and conducted by Kent Nagano, Simon METROPOLIS 2 reaches a variety of audiences through Rattle, and Neeme Järvi, among others. live performances, recordings, TV and Awards include the 2004 Grawemeyer for SATURDAY 21 APRIL radio broadcasts and live streaming. her Violin Concerto and last year’s Wihuri Melbourne Symphony Orchestra The MSO also works with Associate Sibelius Prize. The Bavarian State Opera Clark Rundell conductor Conductor Benjamin Northey and Cybec production of Alice in Wonderland was Assistant Conductor Tianyi Lu, as well as selected ‘Premiere of the Year’ in 2007 by Jennifer Koh violin with such eminent recent guest conductors the German opera magazine Opernwelt.