PGT Course Details Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Thin, white, and saved : fat stigma and the fear of the big black body Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/55p6h2xt Author Strings, Sabrina A. Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Thin, White, and Saved: Fat Stigma and the Fear of the Big Black Body A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Sabrina A. Strings Committee in charge: Professor Maria Charles, Co-Chair Professor Christena Turner, Co-Chair Professor Camille Forbes Professor Jeffrey Haydu Professor Lisa Park 2012 Copyright Sabrina A. Strings, 2012 All rights reserved The dissertation of Sabrina A. Strings is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 i i i DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my grandmother, Alma Green, so that she might have an answer to her question. i v TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE …………………………………..…………………………….…. iii DEDICATION …...…....................................................................................................... iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ……………………………………………………....................v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS …………………...…………………………………….…...vi VITA…………………………..…………………….……………………………….…..vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION………………….……....................................viii -

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences

Shrews, Moneylenders, Soldiers, and Moors: Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Harelik, M.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Professor Lesley Ferris, Adviser Professor Jennifer Schlueter Professor Shilarna Stokes Professor Robin Post Copyright by Elizabeth Harelik 2016 Abstract Shakespeare’s plays are often a staple of the secondary school curriculum, and, more and more, theatre artists and educators are introducing young people to his works through performance. While these performances offer an engaging way for students to access these complex texts, they also often bring up topics and themes that might be challenging to discuss with young people. To give just a few examples, The Taming of the Shrew contains blatant sexism and gender violence; The Merchant of Venice features a multitude of anti-Semitic slurs; Othello shows characters displaying overtly racist attitudes towards its title character; and Henry V has several scenes of wartime violence. These themes are important, timely, and crucial to discuss with young people, but how can directors, actors, and teachers use Shakespeare’s work as a springboard to begin these conversations? In this research project, I explore twenty-first century productions of the four plays mentioned above. All of the productions studied were done in the United States by professional or university companies, either for young audiences or with young people as performers. I look at the various ways that practitioners have adapted these plays, from abridgments that retain basic plot points but reduce running time, to versions incorporating significant audience participation, to reimaginings created by or with student performers. -

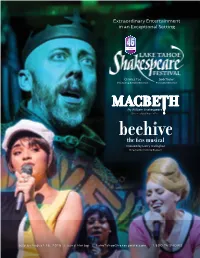

Extraordinary Entertainment in an Exceptional Setting

Extraordinary Entertainment in an Exceptional Setting Charles Fee Bob Taylor Producing Artistic Director Executive Director By William Shakespeare Directed by Charles Fee Created by Larry Gallagher Directed by Victoria Bussert July 6–August 26, 2018 | Sand Harbor | L akeTahoeShakespeare.com | 1.800.74.SHOWS Enriching lives, inspiring new possibilities. At U.S. Bank, we believe art enriches and inspires our community. That’s why we support the visual and performing arts organizations that push our creativity and passion to new levels. When we test the limits of possible, we fi nd more ways to shine. usbank.com/communitypossible U.S. Bank is proud to support the Lake Tahoe Shakespeare Festival. Incline Village Branch 923 Tahoe Blvd. Incline Village, NV 775.831.4780 ©2017 U.S. Bank. Member FDIC. 171120c 8.17 “World’s Most Ethical Companies” and “Ethisphere” names and marks are registered trademarks of Ethisphere LLC. 2018 Board of Directors Patricia Engels, Chair Michael Chamberlain, Vice Chair Atam Lalchandani, Treasurer Mary Ann Peoples, Secretary Wayne Cameron Scott Crawford Katharine Elek Amanda Flangas John Iannucci Vicki Kahn Charles Fee Bob Taylor Nancy Kennedy Producing Artistic Director Executive Director Roberta Klein David Loury Vicki McGowen Dear Friends, Judy Prutzman Welcome to the 46th season of Lake Tahoe Shakespeare Festival, Nevada’s largest professional, non-profit Julie Rauchle theater and provider of educational outreach programming! Forty-six years of Shakespeare at Lake Tahoe D.G. Menchetti, Director Emeritus is a remarkable achievement made possible by the visionary founders and leaders of this company, upon whose shoulders we all stand, and supported by the extraordinary generosity of this community, our board Allen Misher, Director Emeritus of directors, staff, volunteers, and the many artists who have created hundreds of evenings of astonishing Warren Trepp, Honorary Founder entertainment under the stars. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

SUPPORT FOR THE 2021 SEASON OF THE TOM PATTERSON THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY THE HARKINS & MANNING FAMILIES IN MEMORY OF SUSAN & JIM HARKINS LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

Postmaster and the Merton Record 2019

Postmaster & The Merton Record 2019 Merton College Oxford OX1 4JD Telephone +44 (0)1865 276310 www.merton.ox.ac.uk Contents College News Edited by Timothy Foot (2011), Claire Spence-Parsons, Dr Duncan From the Acting Warden......................................................................4 Barker and Philippa Logan. JCR News .................................................................................................6 Front cover image MCR News ...............................................................................................8 St Alban’s Quad from the JCR, during the Merton Merton Sport ........................................................................................10 Society Garden Party 2019. Photograph by John Cairns. Hockey, Rugby, Tennis, Men’s Rowing, Women’s Rowing, Athletics, Cricket, Sports Overview, Blues & Haigh Awards Additional images (unless credited) 4: Ian Wallman Clubs & Societies ................................................................................22 8, 33: Valerian Chen (2016) Halsbury Society, History Society, Roger Bacon Society, 10, 13, 36, 37, 40, 86, 95, 116: John Cairns (www. Neave Society, Christian Union, Bodley Club, Mathematics Society, johncairns.co.uk) Tinbergen Society 12: Callum Schafer (Mansfield, 2017) 14, 15: Maria Salaru (St Antony’s, 2011) Interdisciplinary Groups ....................................................................32 16, 22, 23, 24, 80: Joseph Rhee (2018) Ockham Lectures, History of the Book Group 28, 32, 99, 103, 104, 108, 109: Timothy Foot -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

St Andrews Institute of Legal and Constitutional Research

St Andrews Institute of Legal and Constitutional Research 2016-17 Report Now in its second year, the St Andrews Institute of Legal and Constitutional Research (ILCR) has built upon its successes in the 2015 - 2016 academic year and experienced another busy, enjoyable, and intellectually stimulat- ing period of activity. Over the past year, the ILCR has enjoyed success in a number of areas: internationally recognised academic pub- lications; innovative public engagement activities; unique research projects; world-leading workshops; and the award of major research grants. At the beginning of the 2016 Martinmas term the ILCR also welcomed the first students on the Institute’s new Legal and Constitutional Research M.Litt, studying a range of topics including international law, political history and medieval and early-modern law. The 2017 - 2018 academic year promises to be equally stimulating. It will witness the first full year of activity on a major ERC Advanced Grant funded project on medieval legal history undertaken within the ILCR, the arrival of the second cohort of students taking the Legal and Constitutional Research M.Litt degree, and the development of further innovative research projects. This report contains information about the activities of the Institute and its members over the course of the 2016 - 2017 academic year. Contents Events and research activities: 2 Conferences and colloquiums: 3 Visiting scholars: 4 Awards and other news: 5 Publications and research: 6 - 7 The Legal and Constitutional Studies M.Litt 2016 - 2017 cohort with Professor Caroline Humfress: Photo - Friederike Ritzmann School of History, University of St Andrews, 71 South Street, St Andrews, Fife, KY16 9QW [email protected] 2016-2017 Events and Research Activities Lectures Annual Lecture (April 2017): The ILCR’s Annual Lecture was given by Professor William Ian Miller (Thomas G. -

Winner of the Wolfson History Prize 2017 Announced

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release Monday 15 May 2017 WINNER OF THE WOLFSON HISTORY PRIZE 2017 ANNOUNCED The winner of this year’s Wolfson History Prize, awarded for excellence in accessible and scholarly history, has been announced as Dr Christopher de Hamel for his book Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts. De Hamel, who receives the £40,000 prize, is Fellow and former librarian of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. He was one of six authors shortlisted for the Prize earlier this year. Awarded annually by the Wolfson Foundation for over forty years, the Wolfson History Prize has become synonymous with celebrating outstanding history. Established in 1972, it has awarded more than £1.1 million in recognition of the best historical writing being produced in the UK, reflecting qualities of both readability and excellence in writing and research. Sir David Cannadine, Chair of the Prize Judges, said: “Christopher de Hamel's outstanding and original book pushes the boundaries of what it is and what it means to write history. By framing each manuscript of which he writes as the story of his own personal encounter with it, he leads the reader on many unforgettable journeys of discovery and learning. Deeply imaginative, beautifully written, and unfailingly humane, Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts distils a lifelong love of these astonishing historical treasures, which the author brings so vividly to life. It is a masterpiece.” About the Prize-winning book: Part travel book, part detective story, part conversation with the reader, Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts conveys the fascination and excitement of encountering some of the greatest works of art in our culture which, in the originals, are to most people completely inaccessible. -

Download Original Attachment

FACULTY OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE M.St./M.Phil. English Course Details 2015-16 Further programnme information is available in the M.St./M.Phil. Handbook CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO THE… M.St. in English Literature (by period, English and American and World Literatures) 4 M.St. in English Language 6 M.Phil. in English (Medieval Studies) 8 STRAND SPECIFIC COURSE DESCRIPTIONS (A- and Hilary Term B- Courses) M.St. 650-1550/first year M.Phil. (including Michaelmas Term B-Course) 9 M.St. 1550-1700 18 M.St. 1700-1830 28 M.St. 1830-1914 35 M.St. 1900-present 38 M.St. English and American Studies 42 M. St. World Literatures in English 46 M.St. English Language (including Michaelmas Term B-Course) 51 B-COURSE, POST-1550 - MICHAELMAS TERM 62 Material Texts, 1550-1830 63 Material Texts, 1830-1914 65 Material Texts, Post-1900 66 Transcription Classes 71 C-COURSES - MICHAELMAS TERM You can select any C-Course The Age of Alfred 72 The Language of Middle English Literature 73 Older Scots Literature 74 Tragicomedy from the Greeks to Shakespeare 77 Documents of Theatre History 80 Romantic to Victorian: Wordsworth’s Writings 1787-1845 85 Literature in Brief 86 Women’s Poetry 1700-1830 89 Aestheticism, Decadence and the Fin de Siècle 91 Late Modernist Poetry in America and Britain 93 High Modernism at play: Modernists and Children’s Literature 94 Reading Emerson 95 Theories of World Literature 96 Legal Fictions: Law in Postcolonial and World Literature 99 Lexicography 101 2 C-COURSES - HILARY TERM You can select any C-Course The Anglo-Saxon Riddle -

LIVES in BOOK TRADE HISTORY Changing Contours of Research Over 40 Years

40th Annual Conference on Book Trade History LIVES IN BOOK TRADE HISTORY Changing contours of research over 40 years Sunday 25 & Monday 26 November 2018 at Stationers’ Hall Ave Maria Lane, London EC4M 7DD Organised by Robin Myers, Michael Harris & Giles Mandelbrote in association with the ABA Educational Trust INTRODUCTION In celebration of the 40th year of the conference series, this year’s conference on book trade history will explore themes and developments in this field through the eyes and experience of some of its most widely respected exponents. Leading authorities will discuss their engagement with book trade history, looking back over their own work to identify significant influences upon them and changes in focus and research methods over time. THE SPEAKERS Maureen Bell’s earliest research was into the activities of women in the 16th- and 17th-century book trades. She worked on vol. 4 of The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain and edited, with D.F. McKenzie, A Chronology and Calendar of Documents Relating to the London Book Trade 1641-1700. Formerly Director of the British Book Trade Index, she is on the editorial board of the Cambridge project ‘Editing Aphra Behn in the Digital Age’. Peter W. M. Blayney is Adjunct Professor of English at the University of Toronto and Distinguished Fellow of the Folger Shakespeare Library, and has published on a variety of aspects of the book trade in early modern London. At present he is working on both a study of the Elizabethan Book of Common Prayer and a sequel (extending to 1616) to The Stationers’ Company and the Printers of London, 1501–1557. -

Read Keith Thomas' the Wolfson History Prize 1972-2012

THE WOLFSON HISTORY PRIZE 1972-2012 An Informal History Keith Thomas THE WOLFSON HISTORY PRIZE 1972-2012 An Informal History Keith Thomas The Wolfson Foundation, 2012 Published by The Wolfson Foundation 8 Queen Anne Street London W1G 9LD www.wolfson.org.uk Copyright © The Wolfson Foundation, 2012 All rights reserved The Wolfson Foundation is grateful to the National Portrait Gallery for allowing the use of the images from their collection Excerpts from letters of Sir Isaiah Berlin are quoted with the permission of the trustees of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust, who own the copyright Printed in Great Britain by The Bartham Group ISBN 978-0-9572348-0-2 This account draws upon the History Prize archives of the Wolfson Foundation, to which I have been given unrestricted access. I have also made use of my own papers and recollections. I am grateful to Paul Ramsbottom and Sarah Newsom for much assistance. The Foundation bears no responsibility for the opinions expressed, which are mine alone. K.T. Lord Wolfson of Marylebone Trustee of the Wolfson Foundation from 1955 and Chairman 1972-2010 © The Wolfson Foundation FOREWORD The year 1972 was a pivotal one for the Wolfson Foundation: my father, Lord Wolfson of Marylebone, became Chairman and the Wolfson History Prize was established. No coincidence there. History was my father’s passion and primary source of intellectual stimulation. History books were his daily companions. Of all the Foundation’s many activities, none gave him greater pleasure than the History Prize. It is an immense sadness that he is not with us to celebrate the fortieth anniversary.