Humanizing Mathematics and Its Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

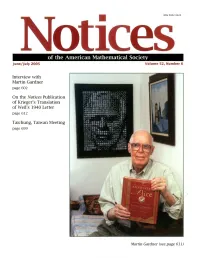

Interview with Martin Gardner Page 602

ISSN 0002-9920 of the American Mathematical Society june/july 2005 Volume 52, Number 6 Interview with Martin Gardner page 602 On the Notices Publication of Krieger's Translation of Weil' s 1940 Letter page 612 Taichung, Taiwan Meeting page 699 ., ' Martin Gardner (see page 611) AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY A Mathematical Gift, I, II, Ill The interplay between topology, functions, geometry, and algebra Shigeyuki Morita, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan, Koji Shiga, Yokohama, Japan, Toshikazu Sunada, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan and Kenji Ueno, Kyoto University, Japan This three-volume set succinctly addresses the interplay between topology, functions, geometry, and algebra. Bringing the beauty and fun of mathematics to the classroom, the authors offer serious mathematics in an engaging style. Included are exercises and many figures illustrating the main concepts. It is suitable for advanced high-school students, graduate students, and researchers. The three-volume set includes A Mathematical Gift, I, II, and III. For a complete description, go to www.ams.org/bookstore-getitem/item=mawrld-gset Mathematical World, Volume 19; 2005; 136 pages; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3282-4; List US$29;AII AMS members US$23; Order code MAWRLD/19 Mathematical World, Volume 20; 2005; 128 pages; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3283-2; List US$29;AII AMS members US$23; Order code MAWRLD/20 Mathematical World, Volume 23; 2005; approximately 128 pages; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3284-0; List US$29;AII AMS members US$23; Order code MAWRLD/23 Set: Mathematical World, Volumes 19, 20, and 23; 2005; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3859-8; List US$75;AII AMS members US$60; Order code MAWRLD-GSET Also available as individual volumes .. -

Linking Together Members of the Mathematical Carlos Rocha, University of Lisbon; Jean Taylor, Cour- Community from the US and Abroad

NEWSLETTER OF THE EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Features Epimorphism Theorem Prime Numbers Interview J.-P. Bourguignon Societies European Physical Society Research Centres ESI Vienna December 2013 Issue 90 ISSN 1027-488X S E European M M Mathematical E S Society Cover photo: Jean-François Dars Mathematics and Computer Science from EDP Sciences www.esaim-cocv.org www.mmnp-journal.org www.rairo-ro.org www.esaim-m2an.org www.esaim-ps.org www.rairo-ita.org Contents Editorial Team European Editor-in-Chief Ulf Persson Matematiska Vetenskaper Lucia Di Vizio Chalmers tekniska högskola Université de Versailles- S-412 96 Göteborg, Sweden St Quentin e-mail: [email protected] Mathematical Laboratoire de Mathématiques 45 avenue des États-Unis Zdzisław Pogoda 78035 Versailles cedex, France Institute of Mathematicsr e-mail: [email protected] Jagiellonian University Society ul. prof. Stanisława Copy Editor Łojasiewicza 30-348 Kraków, Poland Chris Nunn e-mail: [email protected] Newsletter No. 90, December 2013 119 St Michaels Road, Aldershot, GU12 4JW, UK Themistocles M. Rassias Editorial: Meetings of Presidents – S. Huggett ............................ 3 e-mail: [email protected] (Problem Corner) Department of Mathematics A New Cover for the Newsletter – The Editorial Board ................. 5 Editors National Technical University Jean-Pierre Bourguignon: New President of the ERC .................. 8 of Athens, Zografou Campus Mariolina Bartolini Bussi GR-15780 Athens, Greece Peter Scholze to Receive 2013 Sastra Ramanujan Prize – K. Alladi 9 (Math. Education) e-mail: [email protected] DESU – Universitá di Modena e European Level Organisations for Women Mathematicians – Reggio Emilia Volker R. Remmert C. Series ............................................................................... 11 Via Allegri, 9 (History of Mathematics) Forty Years of the Epimorphism Theorem – I-42121 Reggio Emilia, Italy IZWT, Wuppertal University [email protected] D-42119 Wuppertal, Germany P. -

OF the AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY 157 Notices February 2019 of the American Mathematical Society

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) Notices ofof the American MathematicalMathematical Society February 2019 Volume 66, Number 2 THE NEXT INTRODUCING GENERATION FUND Photo by Steve Schneider/JMM Steve Photo by The Next Generation Fund is a new endowment at the AMS that exclusively supports programs for doctoral and postdoctoral scholars. It will assist rising mathematicians each year at modest but impactful levels, with funding for travel grants, collaboration support, mentoring, and more. Want to learn more? Visit www.ams.org/nextgen THANK YOU AMS Development Offi ce 401.455.4111 [email protected] A WORD FROM... Robin Wilson, Notices Associate Editor In this issue of the Notices, we reflect on the sacrifices and accomplishments made by generations of African Americans to the mathematical sciences. This year marks the 100th birthday of David Blackwell, who was born in Illinois in 1919 and went on to become the first Black professor at the University of California at Berkeley and one of America’s greatest statisticians. Six years after Blackwell was born, in 1925, Frank Elbert Cox was to become the first Black mathematician when he earned his PhD from Cornell University, and eighteen years later, in 1943, Euphemia Lofton Haynes would become the first Black woman to earn a mathematics PhD. By the late 1960s, there were close to 70 Black men and women with PhDs in mathematics. However, this first generation of Black mathematicians was forced to overcome many obstacles. As a Black researcher in America, segregation in the South and de facto segregation elsewhere provided little access to research universities and made it difficult to even participate in professional societies. -

Proving Is Convincing and Explaining

REUBEN HERSH PROVING IS CONVINCING AND EXPLAINING ABSTRACT. In mathematical research, the purpose of proof is to convince. The test of whether something is a proof is whether it convinces qualified judges. In the classroom, on the other hand, the purpose of proof is to explain. Enlightened use of proofs in the mathematics classroom aims to stimulate the students' understanding, not to meet abstract standards of "rigor" or "honesty." I. WHAT IS PROOF? This is one question we mathematics teachers and students would normally never think of asking. We've seen proofs, we've done proofs. Proof is what we've been watching and doing for 10 or 20 years! In the Mathematical Experience (Davis and Hersh, 1981, pp. 39-40) this almost unthinkable question is asked of the Ideal Mathematician (the I.M. - the most mathematician-like mathematician) by a student of philosophy: "What is a mathematical proof?" The I.M. responds with examples - the Fundamental Theorem of This, the Fundamental Theorem of That. But the philosophy student wants a general definition, not just some examples. The I.M. tells the philosophy student about proof as it's portrayed in formal logic: permutation of logical symbols according to certain formal rules. But the philosophy student has seen proofs in mathematics classes, and none of them fit this description. The Ideal Mathematician crumbles. He confides that formal logic is rarely employed in proving theorems, that the real truth of the matter is that a proof is just a convincing argument, as judged by competent judges. The philosophy student is appalled by this betrayal of logical standards. -

NRC Aiming for June Launch of Education Board

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA VOLUME 5NUMBER3 MAY-JUNE 1985 NRC Aiming for June Launch of Education Board he National Research Council (NRC) of the National The purpose of the Board, which will report directly to the Academy of Sciences is aiming for a June 1985 launch leadership of the National Research Council, is to provide a Tdate for its new Board on Mathematical Sciences Edu continuing national capability to assess and support edu cation. [See FOCUS, March-April 1985.] cational conditions and needs in the area of mathematical A major step in this direction was taken on April 12-13, sciences education across the country. NRC hopes the Board when the NRC called a meeting of some 50 mathematical will be a practical response to present problems in devel scientists, educators, and administrators to discuss the pre oping quality instruction in mathematical sciences educa liminary plans for the composition, funding, and projects of tion. The Board's activities will be designed to provide advice the Board. Meeting participants included MAA President Lynn and insight to users across the country who seek to rebuild A. Steen; F. Joe Crosswhite, President, National Council of the quality of mathematical sciences education. Teachers of Mathematics; Gordon M. Ambach, President, Key issues in precollege mathematical sciences education Council of Chief State School Officers; and Bassam Z. Shak which have been identified for early action by the Board are hashiri, Assistant Director, Science and Engineering Edu testing, curriculum guidelines, staff development, commu cation Directorate of the National Science Foundation. The nication and dissemination, and computer-enhanced math meeting was chaired by James Ebert, President of the Car ematics education. -

1970-2020 TOPIC INDEX for the College Mathematics Journal (Including the Two Year College Mathematics Journal)

1970-2020 TOPIC INDEX for The College Mathematics Journal (including the Two Year College Mathematics Journal) prepared by Donald E. Hooley Emeriti Professor of Mathematics Bluffton University, Bluffton, Ohio Each item in this index is listed under the topics for which it might be used in the classroom or for enrichment after the topic has been presented. Within each topic entries are listed in chronological order of publication. Each entry is given in the form: Title, author, volume:issue, year, page range, [C or F], [other topic cross-listings] where C indicates a classroom capsule or short note and F indicates a Fallacies, Flaws and Flimflam note. If there is nothing in this position the entry refers to an article unless it is a book review. The topic headings in this index are numbered and grouped as follows: 0 Precalculus Mathematics (also see 9) 0.1 Arithmetic (also see 9.3) 0.2 Algebra 0.3 Synthetic geometry 0.4 Analytic geometry 0.5 Conic sections 0.6 Trigonometry (also see 5.3) 0.7 Elementary theory of equations 0.8 Business mathematics 0.9 Techniques of proof (including mathematical induction 0.10 Software for precalculus mathematics 1 Mathematics Education 1.1 Teaching techniques and research reports 1.2 Courses and programs 2 History of Mathematics 2.1 History of mathematics before 1400 2.2 History of mathematics after 1400 2.3 Interviews 3 Discrete Mathematics 3.1 Graph theory 3.2 Combinatorics 3.3 Other topics in discrete mathematics (also see 6.3) 3.4 Software for discrete mathematics 4 Linear Algebra 4.1 Matrices, systems -

Introduction to Representation Theory

Introduction to representation theory by Pavel Etingof, Oleg Golberg, Sebastian Hensel, Tiankai Liu, Alex Schwendner, Dmitry Vaintrob, and Elena Yudovina with historical interludes by Slava Gerovitch Contents Chapter 1. Introduction 1 Chapter 2. Basic notions of representation theory 5 x2.1. What is representation theory? 5 x2.2. Algebras 8 x2.3. Representations 10 x2.4. Ideals 15 x2.5. Quotients 15 x2.6. Algebras defined by generators and relations 17 x2.7. Examples of algebras 17 x2.8. Quivers 19 x2.9. Lie algebras 22 x2.10. Historical interlude: Sophus Lie's trials and transformations 26 x2.11. Tensor products 31 x2.12. The tensor algebra 35 x2.13. Hilbert's third problem 36 x2.14. Tensor products and duals of representations of Lie algebras 37 x2.15. Representations of sl(2) 37 iii iv Contents x2.16. Problems on Lie algebras 39 Chapter 3. General results of representation theory 43 x3.1. Subrepresentations in semisimple representations 43 x3.2. The density theorem 45 x3.3. Representations of direct sums of matrix algebras 47 x3.4. Filtrations 49 x3.5. Finite dimensional algebras 49 x3.6. Characters of representations 52 x3.7. The Jordan-H¨oldertheorem 53 x3.8. The Krull-Schmidt theorem 54 x3.9. Problems 56 x3.10. Representations of tensor products 59 Chapter 4. Representations of finite groups: Basic results 61 x4.1. Maschke's theorem 61 x4.2. Characters 63 x4.3. Examples 64 x4.4. Duals and tensor products of representations 67 x4.5. Orthogonality of characters 67 x4.6. Unitary representations. Another proof of Maschke's theorem for complex representations 71 x4.7. -

Mathematics and Philosophy

P1: KPB MABK002-02 MABK002/Gold May 29, 2008 15:49 2 Implications of Experimental Mathematics for the Philosophy of Mathematics1 Jonathan Borwein2 Faculty of Computer Science Dalhousie University From the Editors When computers were first introduced, they were much more a tool for the other sciences than for mathematics. It was many years before more than a very small subset of mathematicians used them for anything beyond word-processing. Today, however, more and more mathematicians are using computers to actively assist their mathematical research in a range of ways. In this chapter, Jonathan Borwein, one of the leaders in this trend, discusses ways that computers can be used in the development of mathematics, both to assist in the discovery of mathematical facts and to assist in the development of their proofs. He suggests that what mathematics requires is secure knowledge that mathematical claims are true, and an understanding of why they are true, and that proofs are not necessarily the only route to this security. For teachers of mathematics, computers are a very helpful, if not essential, component of a constructivist approach to the mathematics curriculum. Jonathan Borwein holds a Canada Research Chair in the Faculty of Computer Science at Dalhousie University (users.cs.dal.ca/ jborwein/). His research interests include scientific computation, numerical optimization, image reconstruction, computational number theory, experimental mathematics, and collaborative technology. He was the founding Director of the Centre for Experimental and Constructive Mathematics, a Simon Fraser University research center within the Departments of Mathematics and Statistics and Actuarial Science, established in 1993. He has received numerous awards including the Chauvenet Prize of the MAA in 1993 (with 1 The companion web site is at www.experimentalmath.info 2 Canada Research Chair, Faculty of Computer Science, 6050 University Ave, Dalhousie University, Nova Scotia, B3H 1W5 Canada. -

What Is Mathematics, Really? Reuben Hersh Oxford University Press New

What Is Mathematics, Really? Reuben Hersh Oxford University Press New York Oxford -iii- Oxford University Press Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 1997 by Reuben Hersh First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 1997 First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 1999 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hersh, Reuben, 1927- What is mathematics, really? / by Reuben Hersh. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-19-511368-3 (cloth) / 0-19-513087-1 (pbk.) 1. Mathematics--Philosophy. I. Title. QA8.4.H47 1997 510 ′.1-dc20 96-38483 Illustration on dust jacket and p. vi "Arabesque XXIX" courtesy of Robert Longhurst. The sculpture depicts a "minimal Surface" named after the German geometer A. Enneper. Longhurst made the sculpture from a photograph taken from a computer-generated movie produced by differential geometer David Hoffman and computer graphics virtuoso Jim Hoffman. Thanks to Nat Friedman for putting me in touch with Longhurst, and to Bob Osserman for mathematical instruction. The "Mathematical Notes and Comments" has a section with more information about minimal surfaces. Figures 1 and 2 were derived from Ascher and Brooks, Ethnomathematics , Santa Rosa, CA.: Cole Publishing Co., 1991; and figures 6-17 from Davis, Hersh, and Marchisotto, The Companion Guide to the Mathematical Experience , Cambridge, Ma.: Birkhauser, 1995. -

Modern Birkhäuser Classics

Modern Birkhäuser Classics Many of the original research and survey monographs, as well as textbooks, in pure and applied mathematics published by Birkhäuser in recent decades have been groundbreaking and have come to be regarded as foundational to the subject. Through the MBC Series, a select number of these modern classics, entirely uncorrected, are being re-released in paperback (and as eBooks) to ensure that these treasures remain accessible to new genera- tions of students, scholars, and researchers. The Mathematical Experience, Study Edition Philip J. Davis Reuben Hersh Elena Anne Marchisotto Reprint of the 1995 Edition Updated with Epilogues by the Authors Philip J. Davis Reuben Hersh Division of Applied Mathematics Department of Mathematics Brown University and Statistics Providence, RI 02912 University of New Mexico USA Albuquerque, NM 87131 [email protected] USA [email protected] Elena Anne Marchisotto Department of Mathematics California State University, Northridge Northridge, CA 91330 [email protected] Originally published as a hardcover edition under the same title by Birkhäuser Boston, ISBN 978-0-8176-3739-2, ©1995 ISBN 978-0-8176-8294-1 e-ISBN 978-0-8176-8295-8 DOI 10.1007/978-0-8176-8295-8 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Library of Congress Control Number: 2011939204 © Springer Science+B usiness Media, LLC 2012 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. -

Reuben Hersh (1927-2020) in Memoriam

Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 10 | Issue 2 July 2020 The Human Face of Mathematics: Reuben Hersh (1927-2020) In Memoriam Elena Anne Corie Marchisotto California State University, Northridge Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Mathematics Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Marchisotto, E. "The Human Face of Mathematics: Reuben Hersh (1927-2020) In Memoriam," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 10 Issue 2 (July 2020), pages 539-552. DOI: 10.5642/ jhummath.202002.25 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol10/iss2/25 ©2020 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. The Human Face of Mathematics: Reuben Hersh (1927-2020) In Memoriam Cover Page Footnote This memoriam to Reuben Hersh includes parts excerpted from a chapter entitled “A Case -

National Math Festival MIT Wins Putnam Call for Papers at JMM MAA National Positions Filled

0$$)2&86 NEWSMAGAZINE OF THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA, VOL. 35, NO. 3, JUNE/JULY 2015 National Math Festival MIT Wins Putnam Call for Papers at JMM MAA National Positions Filled 0$$)2&86is published by the he MAA Officers Election ended on May 4. The officers elected are Mathematical Association of America in as follows: February/March, April/May, June/July, T August/September, October/November, and December/January. Advertising inquiries: [email protected] MAA FOCUS Staff Director of Publications: Jim Angelo Editor: Ivars Peterson, [email protected] Managing Editor & Art Director: Lois M. Baron, [email protected] Staff Writer: Alexandra Branscombe President-Elect First Vice President Second Vice President Deanna Matt Boelkins Tim Chartier MAA Officers President: Francis Edward Su Haunsperger Grand Valley State Davidson College Past President: Robert L. Devaney Carleton College University First Vice President: Jenna Carpenter Second Vice President: Karen Saxe Two new members of the nominating committee were elected: Secretary: Barbara T. Faires Treasurer: Jim Daniel Chair, Council on Publications and Communications: Jennifer J. Quinn Executive Director Michael Pearson MAA FOCUS Editorial Board Donald J. Albers, Janet L. Beery, David M. Bressoud, Susan J. Colley, Brie Finegold, Joseph A. Gallian, Jacqueline B. Giles, Fernando Q. Gouvêa, Rick Cleary Susan Jane Colley Jacqueline A. Jensen, Colm Mulcahy, Adriana J. Babson College Oberlin College Salerno, Amy Shell-Gellasch, Francis E. Su, Laura Taalman, Gerard A. Venema All terms begin February 1, 2016. The MAA congratulates the new Letters to the editor should be addressed to officers and thanks all who participated in the election. Ivars Peterson, Mathematical Association of America, 1529 18th Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036, or by email to [email protected].