Hoser's Promenade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Reportwednesday APRIL 16, 2014 RUSSIA&INDIA the ECONOMIC TIMES in ASSOCIATION with ROSSIYSKAYA GAZETA, RUSSIA

in.rbth.com Business ReportWEDNESDAY APRIL 16, 2014 RUSSIA&INDIA THE ECONOMIC TIMES IN ASSOCIATION WITH ROSSIYSKAYA GAZETA, RUSSIA DIPLOMACY: Economic rapprochement with the West will continue, but there won’t be blank cheques anymore STATISTICS After Crimea gamble, is Russian Ruble/Rupee dollar rates diplomacy heading for a new era? The Crimea standoff has underlined Moscow’s resolve to draw a line with the West over its vital security interests. Moscow will now be increasingly looking East to protect and promote its economic and geopolitical interests. DMITRY BABICH RIBR Stock Market Index oes Russia have a new diplomacy after its unilateral action in Crimea, Dwhich is seen as “occupation” by the Western powers and as “reunification” by a majority of the Russians and their allies abroad? There are two extremes in answering this question. One is to say that Moscow is trying to recover its old Soviet might, probably even beyond the borders of the former Soviet Union. The other extreme is to say that what happened in Crimea was an “unsuccessful improvisation” and things will soon be back to business as usual – with Russia grudgingly accepting the inclusion into the Western sphere of influence of ever new territories of Putin’s approval rating the former Soviet Union to the tune of talks about “expanding the zone of security and prosperity.” The truth, as always, is between the two extremes. Russia does not want isolation and exclu- sion from the international exchange of la- bour, capitals and knowledge, even though its foes in Euro-Atlantic and EU structures are AP happily tr ying to impose on it just this kind Bold Gamble: Russia’s President Vladimir Putin is poised for a tough diplomatic battle after the controversial Crimea reunification. -

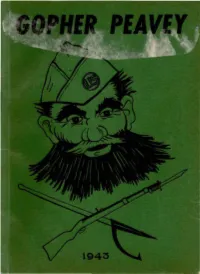

The Gopher Peavey 1943

The Gopher Peavey 1943 GREEN HALL Home of Minnesota Forestry Annual Publicat i on of the Forestry C l ub, University of Minneso ta FOREWORD We worked, fought, argued, and we loafed, laughed, and learned. Our Peavey is out, and we are glad. Our main desire, however, is to have you like it and have the gang in the service receive a little pleasure from it. 1943 Gopher Peavey Staff DEDICATION It would certainly be a fitting thing a t any time to dedicate a state university publica tion to the Governor of the state. However, we are not dedicating this issue to you only as the Governor of Minnesota. We are dedi cating it to you more particularly as an officer in the U.S. Naval Reserve and as the most worthy representa tive of that great company of our students and alumni who have laid down important positions in life to enroll in our armed forces. Lieutenant Commander Stassen, we salute you! And through you all those other Minne sota men who have dedicated themselves to the defense of their country! Table of Contents OUR FORESTRY SCHOOL Faculty 6 Seniors - 8 Juniors - 12 Sophomores - 13 Freshmen 14 ORGANIZATIONS Gopher Peavey Staff - 16 Forestry Club 17 Xi Sigma Pi _ 18 Alpha Zeta 19 FEATURE ARTICLES Forest Conservation and War · 21 We Are It 27 TRADITIONAL ACTIVITIES Foresters' Day 30 Sports 32 ·Bonfire - 33 The Canoe Trip . 34 The Steak Fry 35 SUMMER WORK Freshman Corporation, '42 _ 38 Junior Corporation, '42 _ 41 The Gunflint Trail _ 42 The Southwest , 44 The Northwest 49 ALUMNI SECTION Undergraduates in the Army 53 Incidentals 54 News Fro:rp. -

IIHF 100 Year Review Brochure Cover

TABLE OF CONTENTS SPORT ACTIVITIES 3 IIHF SKILLS CHALLENGE 3 FIRST WORLD WOMEN ‘S U18 CHAMPIONSHIP 5 IIHF WORLD YOUTH HOCKEY TOURNAMENT 5 IIHF WORLD OLDTIMER ’S TOURNAMENT 6 FIRST VICTORIA CUP 8 OFFICIAL IIHF 100 YEAR LOOK AND FEEL 10 IIHF CENTENNIAL ICE RINK 11 PR ACTIVITIES 14 CENTENNIAL ALL -STAR TEAM 14 100 TOP STORIES – THE FINAL COUNTDOWN 15 COMMEMORATION OF THE VICTORIA SKATING RINK 16 IIHF FOUNDATION GALA 17 PUBLICATIONS 18 IIHF CENTENNIAL BOOK 18 IIHF TOP 100 HOCKEY STORIES OF ALL -TIME 19 RE-LAUNCH WWW.IIHF.COM 20 SPECIAL ACTIVITIES 21 IIHF 100 YEAR EXHIBITIONS 21 ARTS & CULTURE 23 IMPLEMENTATION TIMELINE 24 PROJECT MANAGEMENT 25 - Page 2 - SPORT ACTIVITIES IIHF Skills Challenge Season 2007/08 – Worldwide To involve children all over the world in the IIHF 100 th Anniversary, the International Ice Hockey Federation developed a concept of a world wide skills challenge for young male and female ice hockey players up to the age of 15 (1993 born). A global database and website for all test results was supported by video-based test instructions. More than 500 tool kits with shooter tutors had been shipped to the IIHF Member National Associations and the initiative counted more than 4000 participants globally. The IIHF Skills Challenge in Korea 30 IIHF member national associations organized the Skills Challenge tests to determine their most skilled male and female youth ice hockey player. The best players of each participating IIHF member national association were invited to the 2008 IIHF Skills Challenge on the weekend from 2 to 4 May 2008 in Quebec City. -

By-Laws • Regulations • History Effective 2018-2019 Season

By-Laws • Regulations • History Effective 2018-2019 Season HockeyCanada.ca As adopted at Ottawa, December 4, 1914 and amended to May 2018. HOCKEY CANADA BY-L AWS REGULATIONS HISTORY As amended to May 2018 This edition is prepared for easy and convenient reference only. Should errors occur, the contents of this book will be interpreted by the President according to the official minutes of meetings of Hockey Canada. The Playing Rules of Hockey Canada are published in a separate booklet and may be obtained from the Executive Director of any Hockey Canada Member, from any office of Hockey Canada or from Hockey Canada’s web site. HockeyCanada.ca 1 HOCKEY CANADA MISSION STATEMENT Lead, Develop and Promote Positive Hockey Experiences Joe Drago 1283 Montrose Avenue Sudbury, ON P3A 3B9 Chair of the Board Hockey Canada 2018-19 2 HockeyCanada.ca CHAIR’S MESSAGE 2018-2019 The governance model continues to move forward. Operational and Policy Governance are clearly understood. The Board of Directors and Members have adapted well. Again, I stress how pleased I am to work with a team striving to improve our organization and game. The Board recognizes that hockey is a passion with high expectations from our country. The mandatory Initiation Program is experiencing some concern in a few areas; however, I have been impressed with the progress and attitude of the Members actively involved in promoting the value of this program. It is pleasant to receive compliments supporting the Board for this initiative. It is difficult to be critical of a program that works on improvement and develops skills as well as incorporating fun in the game. -

Canada, Hockey and the First World War JJ Wilson

This article was downloaded by: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] On: 9 September 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 783016864] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK International Journal of the History of Sport Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713672545 Skating to Armageddon: Canada, Hockey and the First World War JJ Wilson To cite this Article Wilson, JJ(2005) 'Skating to Armageddon: Canada, Hockey and the First World War', International Journal of the History of Sport, 22: 3, 315 — 343 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09523360500048746 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523360500048746 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

The Birth of Swedish Ice Hockey : Antwerp 1920

The Birth of Swedish Ice Hockey : Antwerp 1920 Hansen, Kenth Published in: Citius, altius, fortius : the ISOH journal 1996 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Hansen, K. (1996). The Birth of Swedish Ice Hockey : Antwerp 1920. Citius, altius, fortius : the ISOH journal, 4(2), 5-27. http://library.la84.org/SportsLibrary/JOH/JOHv4n2/JOHv4n2c.pdf Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 THE BIRTH OF SWEDISH ICE HOCKEY - ANTWERP 1920 by Kenth Hansen Introduction The purpose of this paper is to describe how the Swedes began playing ice hockey and to document the first Olympic ice hockey tournament in Antwerp in 1920, since both events happened at the same time. -

Sam Walker April 23, 2018 My Ego Demands – for Myself – the Success of My Team

What is the Hidden Force that Creates the World’s Greatest Teams? Exploring Leadership in Sports | Sam Walker April 23, 2018 My ego demands – for myself – the success of my team. INTRODUCTION – Bill Russell What’s up everybody? Welcome to this week’s episode of Hidden Forces with me, Demetri Kofinas. Today, I speak with Sam Walker, the Wall Street Journal’s deputy editor for enterprise, the unit that directs the paper’s in-depth page-one features and investigative reporting projects. A former reporter, sports columnist, and sports editor, Walker founded the Journal’s prizewinning daily sports coverage in 2009. Sam is also the author of "The Captain Class: The Hidden Force That Creates the World's Greatest Teams." In addition to The Captain Class, he is the author of Fantasyland, a bestselling account of his attempt to win America’s top fantasy baseball expert competition (of which he is a two-time champion). Sam, welcome to Hidden Forces… WHY DO I CARE? Human beings gravitate naturally towards sports. We love to compete. But our love-affair with athletic performance is not just about rivalry or competition. It’s about so much more. As our lives becomes increasingly intermediated by computer interfaces, spectator sports provide one of the few remaining ways to experience the elegance and power of the human body. In a world that is constantly changing, sports are a window into the old. They offer us a glimpse at millions of years of evolution – the impulses, characteristics, and behavioral urges of our ancestors. In this sense, what interests me most about Sam’s book is that it provides insight about how human beings organize successfully into groups and the unique (and Sam would argue crucial) role of leadership and stewardship in those groups. -

NEWSLETTER Summer 2013

MANITOBA HOCKEY HALL OF FAME NEWSLETTER Summer 2013 Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame to induct 14 individuals and 2013 Induction Dinner honour three teams on Oct. 5 Date: October 5, 2013 Cocktails 5 p.m. in Winnipeg Dinner 6 p.m. The Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame will induct six Location: Canad Inns, Polo Park, Winnipeg players, seven builders and one official in the Fall of Tickets: $120 with a charitable tax receipt. 2013. Three teams also will be honoured. The class of Table of 10 - $1,100 2013 was announced April 15 at a media conference Tickets and Tables can be ordered from: held at the Canad Inns Polo Park in Winnipeg. See pages 3-5 for detailed biographical information. Hall of Fame office Two defencemen, Mike Ford, and Bill Mikkelson, 43 Dickens Drive, Winnipeg R3K OM1 played junior for the both the Brandon Wheat Kings and Winnipeg Jets before moving on to successful pro President Gary Cribbs: careers. Four forwards were selected for induction. email: [email protected] Former Winnipeg Blue Bombers running back Gerry Phone: 204-837-4159 James won a Memorial Cup with the Toronto Marlboros and played for the Toronto Maple Leafs. He got his start at Sir John Franklin Community Club in Winnipeg’s River Heights area. Vaughn Karpan from Fleming's coaching resume included stints at the U The Pas played junior in Brandon, at the University of of M, Europe, the NHL and as an associate coach Manitoba and then spent several seasons with with Canada's gold medal winning team at the Canada's National Team. -

Kennaraháskóli Íslands

Fálkarnir Sigur Vestur-Íslendinga á Ólympíuleikunum árið 1920 Soffía Björg Sveinsdóttir Lokaverkefni til M.Ed.-prófs Háskóli Íslands Menntavísindasvið Fálkarnir Sigur Vestur-Íslendinga á Ólympíuleikunum árið 1920 Soffía Björg Sveinsdóttir Lokaverkefni til M.Ed.-prófs í íþrótta- og heilsufræði Leiðbeinandi: Guðmundur Sæmundsson Íþrótta-, tómstunda- og þroskaþjálfadeild Menntavísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Febrúar 2012 3 Fálkarnir – Sigur Vestur-Íslendinga á Ólympíuleikunum árið 1920. Ritgerð þessi er 40 eininga lokaverkefni til meistaraprófs við Íþrótta-, tómstunda- og þroskaþjálfadeild, Menntavísindasviðs Háskóla Íslands. © 2012 Soffía Björg Sveinsdóttir Ritgerðina má ekki afrita nema með leyfi höfundar. Prentun: Háskólaprent ehf. Reykjavík, 2012. 4 Formáli Rannsókn þessi er meistaraprófsverkefni til M.Ed.-gráðu í íþrótta- og heilsufræðum við Menntavísindasvið Háskóla Íslands og er vægi ritgerðarinnar 40 ECTS einingar. Gagnasöfnunin hófst haustið 2009 og hófust skriftir stuttu eftir það. Leiðbeinandi var Guðmundur Sæmundsson, aðjunkt í íslensku við Menntavísindasvið HÍ og doktorsnemi, og sérfræðingur var Ingibjörg Jónsdóttir Kolka, MA í íslensku og doktorsnemi við Menntavísindasvið HÍ. Um prófarkalestur sá Sveinn Herjólfsson. Mig langar að þakka þessum þremur aðilum sérstaklega fyrir alla þá aðstoð sem þeir veittu mér við gerð þessa verkefnis og hvatningu sem var mér mikils virði. Einnig langar mig til að þakka Ólöfu Zóphóníasdóttur fyrir stuðninginn og Jónínu Zóphóníasdóttur fyrir aðstoð við að finna efni. 5 6 Ágrip Árið 1920 vann íshokkílið Fálkanna gull á Ólympíuleikunum fyrir hönd Kanada en lið Fálkanna samanstóð af annarri kynslóð Vestur-Íslendinga fyrir utan einn kanadískan varamann. Ýmislegt mælti á móti því að liðið ætti möguleika á að ná þessum árangri en nefna má að liðið var skipað vinum sem komu úr litlu samfélagi, þeim var meinað að taka þátt í aðalíshokkídeild Winnipeg, þeir voru fátækir og höfðu lítinn frítíma og allir sem höfðu aldur til gegndu herþjónustu stuttu fyrir Ólympíuleikana. -

DID Norsemen Explore Canada's FAR North?

CANADA’s histORY histORY CANADA’s FREE MUSIC DOWNLOADS SEE P. 9 FOR DETAILS A RCTIC VIKINGS RCTIC DID NORSEMEN EXPLORE CANada'S far NORTH? A P RI L - M CANADASHISTORY.CA APRIL-MAY 2014 APRIL-MAY PM40063001 AY 2014 WHEN SMOKING CANADA'S WAS SIR JOHN A. WAS CHIC CIVIL WAR A RACIST? $ 6.95 Display until May 26 Ride the rails in northern MANITOBA & ONTARIO ALL ABOARD WITH CANADA’S HISTORY TraVELS & RAIL TRAVEL TOURS Enjoy the heritage of Northern FIRST FIVE BOOKINGS ON EACH Manitoba and Ontario on two different rail tours in 2014 or put TOUR WILL GET TO ENJOY A your deposit down now for our FREE COPY OF THE BOOK unique trip to Winnipeg and the Festival du Voyageur in 2015. 100 PHOTOS THAT CHANGED CANADA PHOTO: M MACRI PHOTO: BELUGAS & HERITAGE OF CHURCHILL, MB Tuesday July 29 to Monday August 04, 2014 Roundtrip from Winnipeg to Churchill, Manitoba by rail to experience the amazing heritage and wildlife of Northern Manitoba during summer. This 7 day, 6 night tour features sleeping accommodations on the train and hotel stay in Churchill, town and Hudson Bay shoreline tour, Beluga Whale watching & Fort Prince of Wales Tour; Parks Canada restored Train Station Interpretive Centre, The Eskimo Museum’s renowned collection of Inuit art, Cape Merry Historic Site, Port of Churchill tour and additional heritage experiences. Also optional tour to historic Sloops Cove or a Dog Sled Experience. Price $ 1,995.00 CDN + GST per person in a Train Section or $2,195.00 ONLY 34 SPACES In a Train Room based on double occupancy. -

Canada Men All Time Results

Canada vs Nations 04/19/20 Czechoslovakia – Canada 6 9 Friendship Game In Antwerp, Belgium 04/24/20 Czechoslovakia – Canada (Winnipeg Falcons) 0 15 Olympic Games In Antwerp, Belgium 04/25/20 United States – Canada (Winnipeg Falcons) 0 2 Olympic Games In Antwerp, Belgium 04/26/20 Sweden – Canada (Winnipeg Falcons) 1 12 Olympic Games In Antwerp, Belgium 01/28/24 Czechoslovakia – Canada (Toronto Granites) 0 30 Olympic Games In Chamonix & Mont-Blanc, France 01/29/24 Sweden – Canada (Toronto Granites) 0 22 Olympic Games In Chamonix & Mont-Blanc, France 01/30/24 Switzerland – Canada (Toronto Granites) 0 33 Olympic Games In Chamonix & Mont-Blanc, France 02/01/24 Great Britain – Canada (Toronto Granites) 2 19 Olympic Games In Chamonix & Mont-Blanc, France 02/03/24 United States – Canada (Toronto Granites) 1 6 Olympic Games In Chamonix & Mont-Blanc, France 02/06/24 Great Britain – Canada (Toronto Granites) 1 17 Friendship Game In Paris, France 02/17/28 Sweden – Canada (Toronto Varsity Grads) 0 11 Olympic Games In Saint Mortiz, Switzerland 02/18/28 Great Britain – Canada (Toronto Varsity Grads) 0 14 Olympic Games In Saint Mortiz, Switzerland 02/19/28 Switzerland – Canada (Toronto Varsity Grads) 0 13 Olympic Games In Saint Mortiz, Switzerland 02/22/28 Austria – Canada (Toronto Varsity Grads) 0 13 Friendship Game In Vienna, Austria 02/26/28 Germany – Canada (Toronto Varsity Grads) 2 12 Friendship Game In Vienna, Austria 01/01/30 Sweden – Canada (Toronto Canadas) 2 3 Friendship Game In Berlin, Germany 01/02/30 Sweden – Canada (Toronto Canadas) 0 2 -

Splendid Condition and Enormous 'Grit'": the Ps Orting "Other" and Canadian Identity

Dialogues: Undergraduate Research in Philosophy, History, and Politics Volume 3 Article 2 2020 "Splendid Condition and Enormous 'Grit'": The pS orting "Other" and Canadian Identity Cassidy L. Jean Thompson Rivers University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.tru.ca/phpdialogues Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Jean, Cassidy L. (2020) ""Splendid Condition and Enormous 'Grit'": The pS orting "Other" and Canadian Identity," Dialogues: Undergraduate Research in Philosophy, History, and Politics: Vol. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.tru.ca/phpdialogues/vol3/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ TRU Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dialogues: Undergraduate Research in Philosophy, History, and Politics by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ TRU Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Splendid Condition and Enormous 'Grit'": The pS orting "Other" and Canadian Identity Abstract Canadian identity is mutable, changing in response to outside influences. This phenomenon is especially apparent in sport. This paper focuses on the formation and maintenance of Canadian identity in sport. By connecting the 1867 Paris rowing crew, the 1972 Summit Series, and the 2019 NBA champion Toronto Raptors, this paper seeks to investigate how Canadian identity has been shaped through sport. Using newspaper articles, online editorials, and academic sources, this paper shows how integral the sporting “other” is to the Canadian identity. Keywords Sport, Identity, Canadian, Summit Series, Toronto Raptors, History, Paris Crew, Media Studies This article is available in Dialogues: Undergraduate Research in Philosophy, History, and Politics: https://digitalcommons.library.tru.ca/phpdialogues/vol3/iss1/2 Jean: The Sporting "Other" and Canadian Identity “Splendid Condition and Enormous ‘Grit’:” The Sporting “Other” and Canadian Identity Cassidy L.