Padua 2017 Abstract Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFE 1882 Magazine Vol 1

1882 N. 01 Welcome to the first edition of 1882, the Symington Family Estates magazine ! CONTENTS FEATURES 4 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN 8 IN MEMORIAM 10 PASSING THE TORCH 14 NEW BEGINNINGS Fifth generation Symingtons joining the family company 18 FIRST BACK-TO-BACK 2017 Vintage Port, our first ever consecutive Vintage Port declaration, following 2016 34 THE JOURNEY SOUTH Quinta da Fonte Souto, Alentejo — our first venture outside the Douro 48 QUALITY AND QUANTITY Overview of the 2019 harvest 58 QUINTA DO VESÚVIO 30TH ANNIVERSARY Celebrating the first three decades of ownership of this legendary property 70 GRAHAM’S PORT – THE BICENTENARY Graham’s fascinating 200-year journey – the story of two families from 1820 to 2020 78 50 YEARS OF COCKBURN’S SPECIAL RESERVE How Special Reserve revolutionised Port and the Douro - plus the recent rebrand 1882 N. 01 SUSTAINABILITY 84 FOR THE NEXT GENERATION Special report on our sustainability strategy 88 KEY INITIATIVES B Corporation certification Mission 2025 The Symington Impact Fund Rewilding Portugal International Wineries for Climate Action Adapting to climate change 98 SUSTAINABILITY SHORTS Examples of our involvement in social, economic and environmental initiatives 100 A VINOUS ROBOT Development of VineScout vineyard monitoring robot 106 BIODIVERSITY RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION COLLABORATION 114 BIRDS OF A FEATHER Supporting UTAD’s Wildlife Rescue Centre NEW RELEASES 120 Graham’s Blend Nº 5 White Port 123 Graham’s The Cellar Master’s Trilogy 126 Warre’s 1960 Private Cellar Vintage Port RECOGNITION -

Tiesthat Bind

OP12 • THEEDGE SINGAPORE | APRIL 23, 2007 BEHIND THE BOTTLE The Hugel family tree show- ing its roots, which can be Ties that bind traced back to 15th century Etienne Hugel shares with Jenny Tan Alsace, when founder Hans Ulrich Hugel settled in the what being part of a family means to him charming town of Riquewihr tienne Hugel can always be counted on for a good has 12 bottles… there are 12 “The Internet will quote, especially when it concerns his family winery, apostles… it’s a lucky number,” revolutionise the wine Hugel & Fils, but things are a little different, just for Hugel explains. Perrin & Fils and business. It will help today. “I hope you don’t mind, but I am here today Tenuta San Guido (producers of us keep in touch with as part of the PFV, and I’d like to speak more about the Sassicaia cult wine) are the consumers,” he says. Ethis family as a whole,” Hugel explains briskly. newly added members but, today, Indeed, years before, He was at the Raffles Hotel Singapore last month with the PFV still remains a group of 11 those who could not visit Al- the Primum Familiae Vini (PFV), a prestigious group made as finding the right member takes sace could experience the harvesting up of the world’s leading wine families. Set up in 1993 to time. “It took us six years to find a season at Hugel & Fils, as he uploaded daily vid- promote and defend the moral values that are integral in new member when Cos d’Estournel eos onto the website. -

OUR WINES. ALL LOCAL Glasses, Carafes, Bottles. All Wines Are

OUR WINES. ALL LOCAL Glasses, Carafes, Bottles. SPARKLING RED 2019 Box Grove Vineyard Prosecco - $9 / 35 2012 Bald Rock Pinot Noir - $46 NV Tahbilk Couselant Chardonnay/Pinot Noir - $59 2018 Antcliffes Chase Pinot Noir - $15 / 45 / 60 NV Fowles Gingers Prince Sparkling Rose - $45 2018 Jo Nash Single Vineyard Pinot Noir - $72 NV The Bend Sparkling Shiraz - $35 2018 McPhersons The Angus Merlot - $36 2019 McPherson Wines ‘La Vue’ White Moscato - $9 / 27 / 34 2018 Tahbilk ‘GSM’ Grenache, Shiraz, Mourvèdre - $59 2017 Elgo Estate ‘Allira’ Shiraz - $9 / 27 / 34 WHITE 2017 Maygars Hill Shiraz - $60 2019 Elgo Estate ‘Allira’ Sauvignon Blanc - $9 / 27 / 34 2015 RPL Barrel Selection Shiraz - $72 2017 Kooyonga Creek Sauvignon Blanc - $39 2010 Hide and Seek Reserve Shiraz – $90 2019 Sibling Rivalry Sauvignon Blanc - $42 2010 Moon Shiraz - $92 2020 RPL No Picnic Pinot Gris - $42 2015 Fowles ‘The Rule Shiraz - $110 2020 Vino Relaxo Riesling - $44 2016 Anderson Fort Shiraz - $145 2019 Whistle & Hope Riesling - $48 2013 Tahbilk ‘1860’ Shiraz - $450 2019 Trust Riesling by Tar & Roses - $48 2016 Municipal Wines ‘Whitegate’ Tempranillo - $60 2019 Antcliffes Chase Riesling - $13 / 39 / 53 2018 Veldhuis Cabernet Sauvignon, Petit Verdot - $51 2020 Mac Forbes Spring Riesling - $65 2015 Elgo Cabernet Sauvignon $53 2018 Brave Goose Vineyard Viognier - $60 2017 Maygars Hill Cabernet Sauvignon - $60 2020 Elgo Estate ‘Allira’ Chardonnay - $34 2017 Sam Plunkett Cabernet Sauvignon - $73 2020 Stardust & Muscle Chardonnay - $11/ 33 / 43 2019 Seneca Cabernet Sauvignon -

Pfv Prize 2021 Cp

THE €100,000 PRIMUM FAMILIAE VINI PRIZE OF 2021 WINNER MAISON BERNARD IN BELGIUM Embargoed till Monday 22nd March 9.00 AM Press Release Europe’s oldest luthier workshop The Primum Familiae Vini are pleased to announce that a jury formed of one member of each of its twelve wine-making families has selected Maison Bernard in Brussels, Europe’s oldest luthier workshop, as the winner of the €100,000 PFV Prize of 2021. Maison Bernard is a world-renowned maker and repairer of violins and is managed by father and son Jan and Matthijs Strick, both famed for their extraordinary knowledge and craftsmanship. Maison Bernard has recently been entrusted with the repair of an almost priceless Stradivarius from 1732. Jan is an international authority on the Flemish th Maison Bernard school of violin making of the 17th and 18 centuries and this award will facilitate Jan’s publication of his book on violins of this period and will finance Matthijs’s travel to Chicago to gain experience with one of the world’s finest violin shops, as well as helping to guarantee the future of this wonderful family enterprise. Under the ‘Family is Sustainability’ motto - together with their long histories and the fame of their wines - the PFV aim to encourage independent family-owned companies to continue their projects and to incentivize product excellence, generational succession, social responsibility and sustainability. These values are paramount to the twelve winemaking PFV Maison Bernard Maison Bernard members. Jan Strick Matthiis Strick Watch the vidéo Maison Bernard, Winner of the 2021 PFV ‘Family is Sustainability' Prize. -

Pallas Wine Brochure Artwork-Final.Indd

PORTFOLIO 2015 Some Benefits to Working with Irelands Largest Supplier to the Catering Trade A Premier Collection of World Class Wines, Artisan Beers and Cider Exclusively Available to the On Trade Our Strategy with Private Vines is to import an exclusive range of wines from around the wine making world, which in turn we keep exclusively for you in the On Trade. Delivery Pallas Foods continue to provide a premium delivery service throughout the country. Training Our Wine Specialists will provide a comprehensive training programme for your sta on our wine selection and all aspects of wine service and wine sales. Wine list design We provide our customers with a design and print service so you can present your customer with a professional wine menu incorporating tasting notes on your choice of wines. IN ASSOCIATION WITH IN ASSOCIATION WITH IN ASSOCIATION WITH IN ASSOCIATION WITH IN ASSOCIATION WITH IN ASSOCIATION WITH 2PRIVATE WINES WINE & ARTISAN BEER COLLECTION Our Private Vines catalogue is a Premier Collection of world class wines and now an extended range of Artisan Craft Beers. Our specialist have carefully selected to allow our customers to create a comprehensive wine and beer offering. We import an extensive range of wines from around the world which we make available exclusively to our “Wine is one of the most civilized things customers in the food service industry. in the world and one of the most natural Our Wine Specialists can assist you in developing things of the world that has been your wine list, selecting wines which fit your brought to the greatest perfection, and restaurant’s style and which complement the food it offers a greater range for enjoyment you serve. -

The Goulburn Explorer

What better way to experience the beauty of the Goulburn River than by cruising along its waters in style. The Goulburn Explorer River Cruiser links Mitchelton and Tahbilk, two of Victoria’s best-loved wineries, and the charming township of Nagambie, providing a memorable experience for food and wine lovers. Available for private events, corporate parties and twilight cruises, this 12m vessel seats up to 49 passengers with two open-plan decks, bathroom and audio-visual equipment. Murray River Strathmerton Cobram Situated at the gateway to the Goulburn Valley approximately 90 minutes Nathalia Monichino WINERY from Melbourne’s CBD, The Goulburn Explorer River Cruiser is one of Yarrawonga Echuca Numurkah CRUISES regional Victoria’s must see and do experiences. Goulburn River Tungamah Tongala Kyabram THE GOULBURN VALLEY Dookie Merrigum Shepparton Girgarre Mooroopna WINE REGION Tallis Tatura ITINERARY Stanhope Toolamba Departs from Nagambie Lakes Leisure Park @ 10:30am Murray River Colbinabbin Rushworth Arrives at Tahbilk Winery @ 11:30am Strathmerton Cobram Murchison Departs from Tahbilk Winery @ 12:00pm Longleat Violet Town Arrives at Mitchelton @ 12:30pm Nathalia Monichino Goulburn Valley HWY NYarrawonga Echuca Numurkah Departs Mitchelton @ 2:30pm Nagambie Goulburn Terrace Goulburn River Euroa David Traeger Disembarks at Nagambie Lakes Leisure Park @ 4:00pm Tahbilk Tungamah Tongala Mitchelton Hume FWY Kyabram Avenel Fowles Dookie Merrigum Shepparton Girgarre Mooroopna PRICE Tallis Tatura Stanhope Seymour Toolamba Adult $40pp Rocky Passes -

2016 Marsanne

Nagambie Lakes 2016 MARSANNE WINE REGION: Nagambie Lakes FRUIT SOURCE: Tahbilk Estate GRAPE VARIETY: Marsanne MATURATION: Stainless Steel ACID: 6.2 g/l pH: 3.30 ALCOHOL: 13.5% v/v TOTAL MARSANNE AWARDS 20 88 144 337 VINTAGE 2016 ABOUT THE WINE TASTING NOTES Vintage 2016 started dry with only two thirds of Established in 1860, and purchased by the “2016 Marsanne has distinguishing lemon/lime the average rainfall for winter recorded, followed Purbrick family in 1925, Tahbilk is located in the citrus notes on the nose and palate alongside by half the usual for September and budburst and premium central Victorian viticultural region of floral and herbal hints all wrapped in a zesty then none measurable at all in October. The Nagambie Lakes. minerality. Time in the bottle will deliver the rich vineyard managers were watering two weeks One of the world’s rarest grape varieties, with its honeysuckle and toasty/marmalade characters before budburst and through to January when a origins in the Northern Rhone and Hermitage that are so familiar to aged Marsannes. massive thunderstorm dumped 86 mm of rain in regions of France, Tahbilk’s history with Marsanne Drink Now to 2024/2026” just two hours with some parts of the Old Tahbilk can be traced back to the 1860’s when White vineyards also hit by hail storm damage. Hermitage cuttings were sourced from ‘St Huberts’ Fortunately cool windy days followed with no Vineyard in Victoria’s Yarra Valley. Alister Purbrick ~ Fourth Generation mould or other diseases evident. The grape in fact was Marsanne and although CEO and Winemaker The harvest itself was 'compressed' with many of none of these original plantings have survived, the the red blocks going through veraison at the same Estate has the world’s largest single holding of the time as the whites, leading to the same amount of varietal and produces Marsanne from vines grapes being taken in but in a shorter period of established in 1927, which are amongst the oldest time. -

Hallgarten Druitt

Tahbilk, Nagambie Lakes, Viognier 2020 Intense and fragrant rose petal and ginger spice aromas lead to a softly textured palate of apricot, peach and honeydew melon, lifted by a white peppery finish. Producer Note Established in 1860, Tahbilk is an historic family-owned winery, renowned for their rare aged Marsanne. The estate has the world’s largest single holding of the varietal and produces Marsanne from vines established in 1927, which are among the oldest in the world. Tahbilk is known as ‘tabilk tabilk’ in the language of the Daungwurrung clans, which translates as the ‘place of many waterholes’. It perfectly describes this premium viticultural landscape, which is located in the Nagambie Lakes region of Central Victoria. The estate comprises 1,214 hectares, including a seven mile frontage to the Goulburn River. Environmental sustainability is paramount at Tahbilk and in 2013 they became carbon neutral. In 2016, Tahbilk was awarded 'Winery of the Year' by James Halliday. Vineyard Tahbilk’s vineyards are grouped along the banks of the Goulburn River and an anabranch of it which flows through the estate. The water has a tempering influence on the climate. The vines are grown at approximately 134 metres elevation of gently undulating and flat terrain. The soils are sandy loam with ferric oxide content, which vary from very fine sand near the anabranch to denser loams on the plains. The Viognier vines are clone HTK and are grafted to Schwarzman rootstocks. They are trained on a single wire trellis with a mixture of head and cordon training and are spur pruned. -

2009 Museum Release Marsanne Tahbilk, Victoria, Australia

2009 Museum Release Marsanne Tahbilk, Victoria, Australia Product details Vintage: 2009 Drinking: Now 2020 Producer: Tahbilk Alcohol: Region: Victoria Variety: Marsanne Country: Australia About the producer With its moderate climate, long river and row upon row of Marsanne, Viognier and Syrah vines, Tahbilk is a lovely piece of the Northern Côtes du Rhône. Except that the Tahbilk winery is in the heart of Victoria, Australia - the eucalyptus, acacia and gumtrees around the winery make that very clear, if the 22-hour flight to Melbourne didn’t. The Tahbilk winery’s name comes from the Aboriginal phrase tabilk tabilk, meaning “place of many watering holes” and it is the Nagambie Lakes and surrounding wetlands, linked by the Goulburn River, which make this one of the few places in the world outside the Rhône with the right climate for some of these grapes - in particular Marsanne. In fact, Tahbilk has the largest single acreage of this sensitive grape found anywhere in the world. These bodies of water contribute to cooler temperatures which allow a long hang time, during which complex aromatics can develop. The red, sandy loam - unusual for Victoria - has high levels of ferrous oxide which impart a unique minerality to the wines. Tahbilk was first established in 1860 amid the sort of wheeling, dealing and apocryphal tales as you might expect from frontier times in the wake of a local gold rush. By the end of the century, however, the estate was producing award-winning wines, under the guidance of vigneron François Coueslant. In 1900, phylloxera was found on vines at Tahbilk and over 100 acres of vines were lost. -

2000 Tahbilk Shirazproduct-Timed-Pdf - Central Victoria

Retail Savings $9.99 $25.00 60% 2000 Tahbilk Shirazproduct-timed-pdf - Central Victoria Why We're Drinking It These wines are at their prime: with nice complexity and show some fruit and tannin on the finish. If you don't generally drink aged wines and want to see the difference between a young red and a mature red, these wine are a great way to experiment at a phenomenal price! Established in 1860 Tahbilk is one of Australia's most beautiful & historic wineries. Located in the Nagambie Lakes region of central Victoria (120kms north of Melbourne), one of the nation's premium viticultural areas, the property comprises some 1,214 hectares of rich river flats with a frontage of 11 kms to the Goulburn River and 8 kms of permanent backwaters & creeks. The vineyard comprises 200 hectares of vines including the French Rhone Valley whites of Marsanne, Viognier & Roussanne; the Rhone reds - Shiraz, Grenache & Mourvedre; along with traditional varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay, Riesling, Semillon, Sauvignon Blanc & Verdelho. Vineyard plantings extend back to Tahbilk's founding with original pre-phylloxera Shiraz vines still surviving from 1860 - an eponymous wine produced from them since 1979. Tahbilk is further blessed with an abundance of further "old vine" plantings including Shiraz from 1933 (the prime source for Tahbilk's 'Eric Stevens Purbrick' Shiraz releases), Cabernet Sauvignon back to 1949 and Marsanne from 1927 (a "sister" white release to the 1860 Vines Shiraz produced from them). Harvest commences in early March and continues for five to six weeks with approximately 1,600 tonnes (red & white) grapes processed. -

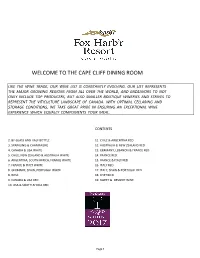

Wine List Is Constantly Evolving

WELCOME TO THE CAPE CLIFF DINING ROOM LIKE THE WINE TRADE, OUR WINE LIST IS CONSTANTLY EVOLVING. OUR LIST REPRESENTS THE MAJOR GROWING REGIONS FROM ALL OVER THE WORLD, AND ENDEAVORS TO NOT ONLY INCLUDE TOP PRODUCERS, BUT ALSO SMALLER BOUTIQUE WINERIES AND STRIVES TO REPRESENT THE VITICULTURE LANDSCAPE OF CANADA. WITH OPTIMAL CELLARING AND STORAGE CONDITIONS, WE TAKE GREAT PRIDE IN ENSURING AN EXCEPTIONAL WINE EXPERIENCE WHICH EQUALLY COMPLIMENTS YOUR MEAL. CONTENTS 2. BY-GLASS AND HALF BOTTLE 11. CHILE & ARGENTINA RED 3. SPARKLING & CHAMPAGNE 12. AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND RED 4. CANADA & USA WHITE 13. GERMANY, LEBANON & FRANCE RED 5. CHILE, NEW ZEALAND & AUSTRALIA WHITE 14. FRANCE RED 6. ARGENTINA, SOUTH AFRICA, FRANCE WHITE 15. FRANCE & ITALY RED 7. FRANCE & ITALY WHITE 16. ITALY RED 8. GERMANY, SPAIN, PORTUGAL WHITE 17. ITALY, SPAIN & PORTUGAL RED 8. ROSÉ 18. FORTIFIED 9. CANADA & USA RED 19. SWEET & DESSERT WINE 10. USA & SOUTH AFRICA RED Page 1 WINES BY THE GLASS AND HALF BOTTLES SPARKLING BOLLA PROSECCO VENETO, ITALY 6oz $11 JÕST, SELKIE FRIZZANTE NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA 6oz $10 JÕST, SELKIE ROSÉ FRIZZANTE NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA 6oz $10 TAITTINGER BRUT CHAMPAGNE, FRANCE 375 ml $60 WHITES BENJAMIN BRIDGE TIDAL BAY NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA 6oz $10 9oz $15 BLOMIDON TIDAL BAY NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA 6oz $10 9oz $15 GASPEREAU TIDAL BAY NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA 6oz $10 9oz $15 JÕST TIDAL BAY NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA 6oz $10 9oz $15 KUNG FU GIRL RIESLING WASHINGTON, USA 6oz $14 9oz $21 SANTA RITA GRAN HACIENDA SAUVIGNON BLANC MAIPO VALLEY, CHILE 6oz $10 9oz $15 SPY VALLEY SAUVIGNNON BLANC MARLBOROUGH, NEW ZEALAND 375 ml $24 6oz $15 9oz $23 VILLA SAN MARTINO PINOT GRIGIO VENETO, ITALY 375 ml $24 6oz $ 9 9oz $13 WENTE MORNING FOG CHARDONNAY CALIFORNIA, USA 6oz $13 9oz $19 Tidal Bay is Canada’s only appellation for Nova Scotia white wine. -

Wines by the Glass Beers Farming Methods

ALL COCKTAILS $13 Brown Derby Old Fashioned Negroni George Dickel Rye, House Bitters Death’s Door Gin, Carpano Antica Old Forester Bourbon, Honey Syrup Demerara Syrup Vermouth, Campari Lemon, Grapefruit Bitters boozy & classic spiritous & bitter Rest in Peace Barbaro Purple rain yes sir! The duke Bulleit Bourbon, Vintage Port, Creme de Peligroso Silver, Vida Mezcal, Lime Old Forester, Zucca Rabarbaro & Apricot Cassis, Lime, Angostura Bitters Green Chartreuse, Luxardo Maraschino Orchard, Manzanilla Sherry, Absinthe Rinse I never meant to cause you any sorrow I never meant to cause you any pain intoxicating & balanced think mr. t as a cocktail oswald cobblepot frenchie hemingway daquiri Don Q Rum, Luxardo Maraschino, Lime Ketel One Vodka, Ginger Syrup, Lime Death’s Door Gin, Peychaud’s Bitters Lemon, Egg White Grapefruit refreshing & spicy pink & proud crisp & sublime WINES BY THE GLASS Sparkling NV Prosecco, Voveti, Veneto, Italy DOC 12 NV Champagne, Piper-Heidsieck, 1785 Brut, France 19 FARMING METHODS Rose Champagne 16 NV , Albert Bichot, Brut Rose, France = sustainable Lambrusco 15 2015 , Medici Ermete, Concerto, Veneto, Italy = organic = biodynamic white 2015 Pinot Grigio, Scarpetta, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Italy 11 2015 Sauvignon Blanc, Miner, Napa, California 14 2015 Pinot Bianco, Le Monde, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Italy 13 2015 Viognier, Tahbilk, Central Victoria, Austrailia 12 2014 Vermentino, Poggio Al Tesoro, ‘Solosole’, Tuscany, Italy 14 2014 Fiano, Salvatore Molettieri, Avellino, Campania, Italy 13 2014 Chardonnay, Neyers, Carneros,