Pepsico's Restaurants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OUTPUT-WSIB Voting Report

2006 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/09/2006 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No.Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.3Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.4Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 2Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Certificate of Incorporation to Declassify the 3Board Mgmt For For For STOCKHOLDER PROPOSAL REGARDING EXECUTIVE 4COMPENSATION ShrHoldr Against Against For STOCKHOLDER PROPOSAL REGARDING 3M S ANIMAL 5WELFARE POLICY ShrHoldr Against Against For STOCKHOLDER PROPOSAL REGARDING 3M S BUSINESS 6OPERATIONS IN CHINA ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/28/2006 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No.Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3Elect W. Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6Elect Jack Greenberg Mgmt For For For 1.7Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.8Elect Boone Powell, Jr. Mgmt For For For 1.9Elect W. Ann Reynolds Mgmt For For For 1.10Elect Roy Roberts Mgmt For For For 1.11Elect William Smithburg Mgmt For For For 1.12Elect John Walter Mgmt For For For 1.13Elect Miles White Mgmt For For For RATIFICATION OF DELOITTE & 2TOUCHE LLP AS AUDITORS. Mgmt For For For SHAREHOLDER PROPOSAL - PAY-FOR-SUPERIOR- 3PERFORMANCE ShrHoldr Against Against For Page 1 of 139 2006 Proxy Voting Report SHAREHOLDER PROPOSAL - 4POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS ShrHoldr Against Against For SHAREHOLDER PROPOSAL - 5THE ROLES OF CHAIR AND CEO . -

Printmgr File

702 Southwest 8th Street Bentonville, Arkansas 72716-0215 (479) 273-4000 Corporate website: www.walmartstores.com NOTICE OF 2011 ANNUAL SHAREHOLDERS’ MEETING To Be Held June 3, 2011 Please join us for the 2011 Annual Shareholders’ Meeting of Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. The meeting will be held on Friday, June 3, 2011, at 7:00 a.m. Central time in Bud Walton Arena, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas. The purposes of the 2011 Annual Shareholders’ Meeting are: (1) to elect as directors the 15 nominees named in the attached proxy statement; (2) to ratify the appointment of Ernst & Young LLP as the company’s independent accountants for the fiscal year ending January 31, 2012; (3) to vote on a non-binding, advisory resolution to approve the compensation of the company’s named executive officers, as described in the Compensation Discussion and Analysis and tabular compensation disclosure in the attached proxy statement; (4) to vote, on a non-binding, advisory basis, regarding the frequency of future advisory votes on the compensation of the company’s named executive officers; (5) to vote on the five shareholder proposals described in the attached proxy statement; and (6) to transact other business properly brought before the 2011 Annual Shareholders’ Meeting. Important Notice Regarding the Availability of Proxy Materials for the 2011 Annual Shareholders’ Meeting. This year, we will once again take advantage of the rules of the Securities and Exchange Commission that allow us to furnish our proxy materials over the internet. As a result, we are mailing a notice of availability of the proxy materials over the internet, rather than a full paper set of the proxy materials, to many of our shareholders. -

Pizza Hut Outparcel to Lowe’S Center

INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY PIZZA HUT OUTPARCEL TO LOWE’S CENTER ST.TILTON, PAUL, MNNH OFFERED AT: $1,826,000 | 5.75% CAP EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PROPERTY INFORMATION TENANT OVERVIEW AREA OVERVIEW TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Offering Summary 5 Investment Highlights 6 Lease Summary & Rent Overview PROPERTY INFORMATION 8 Location Maps 9 Property Photos 11 Neighboring Tenants 13 Aerials TENANT OVERVIEWS 20 About Pizza Hut AREA OVERVIEW 22 Tilton/Concord Overview 23 Demographics Confidentiality Agreement & Disclosures EXCLUSIVELY REPRESENTED BY RYAN BARR RYAN BENNETT Principal Principal 760.448.2446 760.448.2449 [email protected] [email protected] JENNIFER D. STEIN JDS Real Estate Services, Inc. NH Real Estate Broker Lic No. 2738 213.446.5366 Color Scheme RGB R:145 / G:0 / B:40 CMYK C:0 / M:100 / Y:65 / K:47 RGB R:119 / G:120 / B:123 CMYK C:0 / M:0 / Y:0 / K65 Fonts GOTHAM/ BLACK GOTHAM/ MEDIUM GOTHAM/ LIGHT PIZZA HUT | Tilton, NH | 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PIZZA HUT, TILTON NH EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PROPERTY INFORMATION TENANT OVERVIEW AREA OVERVIEW • Offering Summary • Investment Highlights Lease Summary & Rent Overview -- OFFERING SUMMARY -- INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS Offering Price: $1,826,000 Net Operating Income: $105,000 Cap Rate: 5.75% Price/SF: $471 PROPERTY OVERVIEW 15 Lowes Dr Address: Tilton, NH 03276 Property Size: Approx 3,871 Sq. Ft. Ownership: Fee Simple Year Built: 2006 Lee & Associates is pleased to exclusively offer for sale to qualified investors the opportunity to purchase a 100% fee-simple interest in a Pizza Hut property located at 15 Lowes Drive in Tilton, New Hampshire (the “Property). -

Under Fire, Fast Food Giants Switch to Healthier Fare

_______________________________________________________________________ USA Today, McLean, VA Under Fire, Food Giants Switch to Healthier Fare July 1, 2003 Bruce Horovitz <<<>>> This document is available on the Education Policy Studies Laboratory website at http://www.asu.edu/educ/epsl/CERU/Articles/CERU-0307-127-OWI.doc ________________________________________________________________________ Junk food's best consumers are kids -- increasingly obese kids. So that's not the dinner bell you hear. It's an alarm bell raising Oreo-size goose bumps for the giant makers of now-unfashionable sugary, fatty and calorie-laden foods. All are faced with this new reality: As concern about obesity rises, they're within a few cookie crumbs of becoming the next Big Tobacco for trial lawyers. "You can't stop tobacco from being unhealthy," says Sam Hirsch, an attorney whose obese clients filed lawsuits against McDonald's. "But you can make food less unhealthy." Consumer groups are screaming. Parents are steaming. Lawyers are suing. The obese are stewing. Lawmakers are threatening a "fat tax." And some analysts are giving food stocks the ax. That's why, faster than you can say "supersize it," the nation's food behemoths are responding: * Kraft Foods, the nation's largest food company, will announce today a sweeping, global overhaul of the way it creates, packages and promotes its foods. Kraft plans to reduce the portion size, fat and calories of many of its foods, a move that other major food companies worldwide are expected to mimic. "This will force everyone else to review their policies and get on board," says Derek Yach, coordinator of diet and physical activity at the powerful World Health Organization. -

Senior Executive Board Meeting Materials

Senior Executive Board Meeting Materials November 11-12th, 2009 Located in “The Study” at Ritz Carlton - Charlotte, NC Details for Charlotte Board Meeting Ritz Carlton location 201 E Trade St Charlotte, NC 28202 (704) 549-4177 We will be Located in “The Study” at the Ritz Carlton Meal Times 7:45am breakfast November 11 in “The Studio” 12:00pm lunch November 11 in “The Studio” 7:00pm dinner at Bentleys 7:45am breakfast November 12th meeting 12:00pm lunch November 12 in “The Studio” Airports Charlotte Douglas International Airport 11 minutes from the Ritz Carlton Meeting Begins 7:45am November 11th Meeting Ends 5:05pm November 12th Senior Executive Board Meeting: HIGH LEVEL AGENDA High Level Agenda Day 1 Morning– David Noer, author of Revitalizing the Downsized Organization Day 1 Afternoon Jac Fitz-enz, author of the ROI of Human Capital Day 1 Evening Dinner at Bentleys Restaurant at 7:00pm Day 2 Morning– Reuven Bar-On, creator of Bar-On EQ Day 2 Afternoon – Steven Reinemund, former Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo and Dean of Wake Forest University Business School Senior Executive Board Meeting: AGENDA Agenda for Wednesday, November 11th, 2009 7:45 arrive in “The Study” at the Ritz Carlton, Charlotte, NC for breakfast 9:00 Introduction: Louis Carter, founder and Chair, Brian Fishel, Co-Chair 9:30 David Noer addresses group on his new book, Healing the Wounds: Overcoming the Trauma of Layoffs and Revitalizing Downsized Organizations with dialogue and q&a 10:15 Clinic Sessions with David 12:00-1:00 Working Lunch 1:00-2:00 Jac Fitz-enz addresses group on The ROI of Human Capital: Measuring the Economic Value of Employee Performance with dialogue and q&a 2:30-5:00 Clinic Sessions with Jac Fitz-enz 7:00 Dinner at Bentleys Senior Executive Board Meeting: AGENDA Agenda for Thursday, November 12th, 2009 7:45 arrive in "The Study" at the Ritz Carlton, Charlotte, NC for breakfast 9:15: Reuven Bar-On, creator of the Bar-On EQ speaks about Emotional Intelligence and applications to leadership development, recruitment, and retention. -

Cannibalization Definition

CANNIBALIZATION: Cannibalization refers to the notion of a company making a conscious business decision that will have a negative impact on either a current product or member of a distribution channel (or entire channel, via disintermediation). This type of decision is typically designed to allow the company to survive in the long-term, and avoid having its products challenged by competitors' products as technology progresses. PRODUCT BUILDING Product Bundling refers to the bundling together of more than one product for a sale. This is very common for digital products, where the marginal costs of each product is very low. If most of the marginal cost is associated with packaging and distribution, this is further reduced when the products are bundled together, as they share the same costs of packaging and distribution. Thus the incremental cost to the firm (i.e. Microsoft!) for bundling together additional software products is very small (actually zero aside from any opportunity cost). Thus a suite of products may allow for greater market penetration into different software markets than if the software was sold separately. For software that is not currently used by the consumer, but is purchased through a bundled package, it works to lock-in the consumer once he/she decides to use that category of software. Thus bundled software can ensure strong market positions across multiple markets. While product bundling is a regular phenomena for software and related products, product unbundling may occur in the traditional content provider markets as microtransactions can provide payment options for smaller increments of the product. Thus rather than having to buy an entire CD (a bundling of different song titles, mostly of little relevance to each other) the consumer may be able to pay for a single song title, unbundled. -

Business Quiz Page 1 of 73

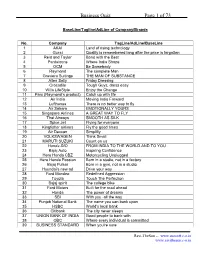

Business Quiz Page 1 of 73 BaseLine/Tagline/AdLine of Company/Brands No. Company TagLine/AdLine/BaseLine 1 AKAI Land of rising technology 2 Gucci Quality is remembered long after the price is forgotten 3 Reid and Taylor Bond with the Best 4 Pantaloons Where India Shops 5 OCM Be Somebody 6 Raymond The complete Man 7 Graviera Suitings THE MAN OF SUBSTANCE 8 Allen Solly Friday Dressing 9 Crocodile Tough Guys, dress easy 10 Wills LifeStyle Enjoy the Change 11 Parx (Raymond’s product) Catch up with life 12 Air India Moving India Forward 13 Lufthansa There is no better way to fly 14 Air Sahara EMOTIONALLY YOURS 15 Singapore Airlines A GREAT WAY TO FLY 16 Thai Airways SMOOTH AS SILK 17 Spice Jet Flying for everyone 18 Kingfisher airlines Fly the good times 19 Air Deccan Simplifly 20 VOLKSWAGEN Think Small 21 MARUTI SUZUKI Count on us 22 Honda DIO FROM INDIA TO THE WORLD.AND TO YOU 23 Bajaj Auto Inspiring Confidence 24 Hero Honda CBZ Motorcycling Unplugged 25 Hero Honda Passion Born in a studio, not in a factory 26 Bajaj Pulsar Born in a gym, not in a studio 27 Hyundai's new ad Drive your way 28 Ford Mondeo Redefined Aggression 29 Toyota Touch The Perfection 30 Bajaj spirit The college bike 31 Ford Motors Built for the road ahead 32 Honda The power of dreams 33 SBI With you all the way 34 Punjab National Bank The name you can bank upon 35 HSBC World's local bank 36 Citibank The city never sleeps 37 UNION BANK OF INDIA Good people to bank with 38 OBC Where every individual is committed 39 BUSINESS STANDARD When you're sure RaviTheSun www.sunsoft.co.in -

Repatriating Offshore Funds: 2004 Tax Windfall for Select Multinationals

United States Senate PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Carl Levin, Chairman Tom Coburn, Ranking Minority Member REPATRIATING OFFSHORE FUNDS: 2004 TAX WINDFALL FOR SELECT MULTINATIONALS MAJORITY STAFF REPORT PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE October 11, 2011 PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS SENATOR CARL LEVIN Chairman ELISE J. BEAN Staff Director and Chief Counsel ROBERT L. ROACH Counsel & Chief Investigator ALLISON F. MURPHY Counsel MARCELLE D. JOHNS Detailee MICHAEL J. MARTINEAU Detailee MARY D. ROBERTSON Chief Clerk 10/20/11 Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations 199 Russell Senate Office Building – Washington, D.C. 20510 Main Number: 202/224-9505 Web Address: www.hsgac.senate.gov [Follow Link to “Subcommittees,” to “Investigations”] REPATRIATING OFFSHORE FUNDS: 2004 TAX WINDFALL FOR SELECT MULTINATIONALS Table of Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................. 3 A. Subcommittee Review ................................................... 3 B. Report Findings ........................................................ 4 1. U.S. Jobs Lost Rather Than Gained ..................................... 4 2. Research and Development Expenditures Did Not Accelerate . 4 3. Stock Repurchases Increased After Repatriation . 4 4. Executive Compensation Increased After Repatriation . 4 5. Only A Narrow Sector of Multinationals Benefited . 4 6. Most Repatriated Funds Flowed from Tax Havens . 4 7. Offshore Funds Increased After -

Who's Who in at Target

Who’s Who in CUSTOMER TEAMS at Target As seen in WHO’S WHO IN CUSTOMER TEAMS AT TARGET ANALYSIS: Temporary Displays at Target We’ve noticed a marked increase in temporary merchandising displays utilized as part of Target’s seasonal campaigns, especially holiday and back-to-school, but even for occasions such as Father’s Day. The activity has been ramping up steadily for the last two years. This began as floorstands in apparel departments, generally merchandis- ing small giftables such as socks and accessories. More recently, they have also stocked such items as Axe body products, Keurig K-Cup packs, and Pepperidge Patrycja Malinowska Farm Goldfish crackers. Associate Director – Content Other departments – grocery, health and beauty immediately come to mind – P2PI.org increasingly utilize sidekicks, power wings (for convenience items such as tape or turkey oven bags) and floorstands (for small giftables). Glorifiers have also made their way onto shelves in the toy department. With few exceptions, the temporary displays are always customized for Target. If pushed to give a very non-scientific guesstimate, I’d say Target saw double the number of temporary displays for holiday 2014 than the previous year. The broader in-store landscape is similarly changing as Target employs a test-and-learn method to quickly try out a variety of new in-store display initiatives. The retailer is killing those that don’t work, while rolling out more successful programs. The initiatives it is keeping seem to be those that help stores tell more stories and provide more well-rounded “experiences.” Must-Know Terms Thought Starters n Cartwheel: A digital savings program launched n Target wants to stock exciting and innovative in 2013 with technological support from Face- merchandise, so provide exclusive product book that offers registered users hundreds of lines, SKUs or packaging – or promotions dan- in-store only discounts redeemable at checkout. -

Leadershipat Every Level

LEADERSHIPAt Every Level Advocacy Education Outreach The National Restaurant Association and the National Restaurant Association Educational Foundation provide leader- ship on many fronts. We advocate poli- cy changes that aid the industry. We mobilize restaurateurs on grassroots issues and philanthropic initiatives. We provide tools to empower operators, advance employees and build our future workforce. We track economic trends that could influence the way our mem- bers do business. Whether you’re a deli owner or fine-dining operator, a family- restaurant proprietor, or a CEO, we work for you. TABLE OF CONTENTS Leading Our Members Forward . .5 Advocating Pro-Restaurant Policies . .7 Serving Our Communities . .11 Promoting the Restaurant Industry . .13 Helping Operators Manage Risk . .15 Empowering Our Workforce . .17 Nurturing Future Workers . .19 Advancing Diversity . .21 Bringing Industry Leaders Together . .23 Hennessy Program Turns 50 . .25 Leadership . .27-39 Photo Credits . .40 NRA Show® 2005 was one of the year’s highlights for the National Restaurant Association, attracting more than 73,000 attendees to Chicago. 2 Dear Colleague: We have never been more proud to be a part of this great industry. It’s been quite a year. Three months after we assumed chairmanship of the National Restaurant Association and National Restaurant Association Educational Foundation last May, Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. Within six weeks, more than 17,000 restaurants from around the country, led by the National Restaurant Association, pulled together in an unprecedented grassroots effort that ultimately raised more than $12.5 million for the American Red Cross’s hurricane-relief efforts. The Dine for America effort is one example of how restaurateurs lead. -

Pepsico Is the World’S Largest Snack Food Company and Is Among the Top Five Largest Food and Beverage Companies in Terms of Annual Revenue

i Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: Organizational Profile............................................................................................ 2 1.1 Operations ................................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Main Customers ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Bottlers...................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Brands....................................................................................................................................... 4 1.5 Executives ................................................................................................................................ 6 1.6 Board of Directors ................................................................................................................... 6 1.7 University Links ....................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter Two: Economic Profile.................................................................................................. 10 2.1 Financial Data........................................................................................................................ -

Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar

Voyage #43 15th April 2010 Students’ Wall Magazine Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar also known as Babasaheb, was an Indian jurist, political lead- er, Buddhist activist, philosopher, thinker, an- thropologist, historian, orator, prolific writer, economist, scholar, editor, revolutionary and a revivalist for Buddhism in India Dr. B.R. Ambedkar was elected as the chairman of the drafting committee that was constituted by the Constituent Assembly to draft a constitution for the independent India; he was the first Law Minister of India; conferred Bharat Ratna in 1990. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar is viewed as messiah of dalits and downtrodden in India. He was the Dr. Bhimrao R. Ambedkar chairman of the drafting committee that was 14 April 1891 - 06 Dec1956 constituted by the Constituent Assembly in 1947 to draft a constitution for the independent India. He played a seminal role in the framing of the constitution. He was the fourteenth child of Ramji and Bhimabai Sakpal Ambavedkar. B.R. Ambedkar belonged to the "untouchable" Mahar Caste. His father and grandfather served in the British Army. In those days, the government ensured that all the army personnel and their children were educated and ran special schools for this purpose. This ensured good education for Bhimrao Ambedkar, which would have otherwise been denied to him by the virtue of his caste. Bhimrao Ambedkar experienced caste discrimination right from the child- hood. After his retirement, Bhimrao's father settled in Satara, Maharashtra. Bhimrao was enrolled in the local school. Here, he had to sit on the floor in one corner in the classroom and teachers would not touch his notebooks.