90Yearson Masterpiecetomass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

Reassessing Marshal Ferdinand Foch

Command in a Coalition War 91 Command in a Coalition War: Reassessing Marshal Ferdinand Foch Elizabeth Greenhalgh* Marshal Ferdinand Foch is remembered, inaccurately, as the unthinking apostle of the offensive, one of the makers of the discredited strategy of the “offensive à outrance” that was responsible for so many French deaths in 1914 and 1915. His acceptance of the German signature on the armistice document presented on behalf of the Entente Allies in 1918 has been overshadowed by postwar conflicts over the peace treaty and then over France’s interwar defense policies. This paper argues that with the archival resources at our disposal it is time to examine what Foch actually did in the years be- tween his prewar professorship at the Ecole Supérieure de Guerre and the postwar disputes at Versailles. I The prewar stereotype of the military leader was influenced by military and diplomat- ic developments on the island of Corsica during the eighteenth century that resulted in the Genoese selling the sovereignty of the island in 1768 to France. This meant that Carlo Buonaparte’s son would be a Frenchman and not Italian, thus altering the face of Europe. The achievements of France’s greatest of “great captains” thus became a benchmark for future French military leaders. A French family from the southwest corner of France near the Pyrenees saw service with Napoleon Bonaparte, and in 1832 one member of that family, named Napoleon Foch for the general, consul and empe- ror, married Mlle Sophie Dupré, the daughter of an Austerlitz veteran. Their second surviving son was named Ferdinand. -

Poland – Germany – History

Poland – Germany – History Issue: 18 /2020 26’02’21 The Polish-French Alliance of 1921 By Prof. dr hab. Stanisław Żerko Concluded in February 1921, Poland’s alliance treaty with France, which was intended to afford the former an additional level of protection against German aggression, was the centerpiece of Poland’s foreign policy during the Interwar Period. However, from Poland’s viewpoint, the alliance had all along been fraught with significant shortcomings. With the passage of time, it lost some of its significance as Paris increasingly disregarded Warsaw’s interests. This trend was epitomized by the Locarno conference of 1925, which marked the beginning of the Franco-German rapprochement. By 1933-1934, Poland began to revise its foreign policy with an eye to turning the alliance into a partnership. This effort turned out to be unsuccessful. It was not until the diplomatic crisis of 1939 that the treaty was strengthened and complemented with an Anglo-Polish alliance, which nevertheless failed to avert the German attack on Poland. Despite both France and Great Britain having declared war against the Reich on September 3, 1939, neither provided their Polish ally with due assistance. However, French support was the main factor for an outcome that was generally favorable to Poland, which was to redraw its border with Germany during the Paris peace conference in 1919. It seems that the terms imposed on the Reich in the Treaty of Versailles were all that Poland could ever have hoped to achieve given the balance of power at the time. One should bear in mind that France made a significant contribution to organizing and arming the Polish Army, especially when the Republic of Poland came under threat from Soviet Russia in the summer of 1920. -

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days

University of Washington Tacoma UW Tacoma Digital Commons History Undergraduate Theses History Winter 3-12-2020 The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days Offensive: Looking at Reconnaissance, Bombing and Pursuit Aviation in the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Operations. Duncan Hamlin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/history_theses Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Hamlin, Duncan, "The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days Offensive: Looking at Reconnaissance, Bombing and Pursuit Aviation in the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Operations." (2020). History Undergraduate Theses. 44. https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/history_theses/44 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UW Tacoma Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of UW Tacoma Digital Commons. The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days Offensive: Looking at Reconnaissance, Bombing and Pursuit Aviation in the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Operations. A Senior Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Undergraduate History Program of the University of Washington By Duncan Hamlin University of Washington Tacoma 2020 Advisor: Dr. Nicoletta Acknowledgments I would first like to thank Dr. Burghart and Dr. Nicoletta for guiding me along with this project. This has been quite the process for me, as I have never had to write a paper this long and they both provided a plethora of sources, suggestions and answers when I needed them. -

Marshal Ferdinand Foch and the British, 1919–1931

Commemorating the Victor: Marshal Ferdinand Foch and the British, 1919–1931 Elizabeth Greenhalgh University of New South Wales Synergies Royaume-Uni Royaume-Uni Summary: There has always been an understandable tension between the justified pride of Sir Douglas Haig in the achievements of the British Army in 23-33 pp. the 1918 victory and the fact that he had accepted an Allied generalissimo et in the person of General Ferdinand Foch and had agreed to place the British Irlande Army under his orders. The agreement barely survived the Armistice, and was destroyed by the treaty negotiations. By 1931, with the publication of Foch’s n° 4 memoirs and Basil Liddell Hart’s biography, the tension had become hostility. This paper charts the decline in Foch’s reputation from the 1919 victory parades, - 2011 through the fuss over the commemorative statue to be erected in London and over the appointment to the new Marshal Foch chair in Oxford University, to the final disenchantment. It argues that the antipathy of the British military and political establishment and the greater influence of the maison Pétain in Paris on French security matters hastened a decline in the esteem which Foch had enjoyed in 1918 and 1919 – a decline which has persisted to this day. Keywords: Foch, Haig, Liddell Hart, commemoration, Great War Résumé : On comprend facilement la tension entre la fierté de Sir Douglas Haig devant les exploits de l’armée britannique pendant la marche à la victoire de 1918 et l’obligation où il s’était trouvé d’accepter un généralissime, le Maréchal Ferdinand Foch, et de placer son armée sous ses ordres. -

Centenary WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas

First World War Centenary WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas www.1914.org WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas - Foreword Foreword The Prime Minister, Rt Hon David Cameron MP The centenary of the First World War will be a truly national moment – a time when we will remember a generation that sacrificed so much for us. Those brave men and boys were not all British. Millions of Australians, Indians, South Africans, Canadians and others joined up and fought with Britain, helping to secure the freedom we enjoy today. It is our duty to remember them all. That is why this programme to honour the overseas winners of the Victoria Cross is so important. Every single name on these plaques represents a story of gallantry, embodying the values of courage, loyalty and compassion that we still hold so dear. By putting these memorials on display in these heroes’ home countries, we are sending out a clear message: that their sacrifice – and their bravery – will never be forgotten. 2 WW1 Victoria Cross Recipients from Overseas - Foreword Foreword FCO Senior Minister of State, Rt Hon Baroness Warsi I am delighted to be leading the commemorations of overseas Victoria Cross recipients from the First World War. It is important to remember this was a truly global war, one which pulled in people from every corner of the earth. Sacrifices were made not only by people in the United Kingdom but by many millions across the world: whether it was the large proportion of Australian men who volunteered to fight in a war far from home, the 1.2 million Indian troops who took part in the war, or the essential support which came from the islands of the West Indies. -

The French Army and the First World War'

H-War Fogarty on Greenhalgh, 'The French Army and the First World War' Review published on Saturday, May 5, 2018 Elizabeth Greenhalgh. The French Army and the First World War. Armies of the Great War Series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. xv + 469 pp. $88.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-107-01235-6; $30.99 (paper), ISBN 978-1-107-60568-8. Reviewed by Richard Fogarty (University at Albany, SUNY)Published on H-War (May, 2018) Commissioned by Margaret Sankey (Air War College) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=46655 Elizabeth Greenhalgh has written an indispensable book on France in the Great War. In fact, the book is indispensable more broadly to the history of the First World War, and to the history of modern France. One of the author’s primary arguments is that English-language historiography all too often underplays the critical importance of the French army to all aspects of the fighting, from the war’s beginning to its very end. After all, “France provided moral leadership” to the Allied coalition “by supplying the largest army of the belligerent democracies” (p. 2), and the decisive western front lay almost entirely in France. But beyond this argument about the war, Greenhalgh shows just how important the French army’s experience in the war was in shaping the nation and argues that by 1919 “the relationship between France and its Army could not have been closer” (p. 401). Since 1870, France had slowly made its army republican, but the war accelerated and finished the job, and joined the institution to the nation of citizens ever more closely. -

Passchendaele – Canada's Other Vimy Ridge

MILITARY HISTORY Canadian War Museum CWM8095 Canadian Gunners in the Mud, Passchendaele 1917, by Alfred Bastien. PASSCHENDAELE – CANADA’S OTHERVIMYRIDGE by Norman S. Leach ...I died in Hell (they called it Passchendaele) through the mud again and amid the din of the my wound was slight and I was hobbling back; and bursting shells I called to Stephens, but got then a shell burst slick upon the duckboards; no response and just assumed he hadn’t heard me. so I fell into the bottomless mud, and lost the light. He was never seen or heard from again. He had not deserted. He had not been captured. One – Siegfried Sassoon of those shells that fell behind me had burst and Stephens was no more. Introduction – Private John Pritchard Sudbury ...At last we were under enemy gunfire and Wounded at Passchendaele I knew now that we had not much further to carry 26 October 1917.1 all this weight. We were soaked through with rain and perspiration from the efforts we had been By the spring of 1917, it was clear that the Allies were making to get through the clinging mud, so in trouble on the Western Front. British Admiral Jellicoe that when we stopped we huddled down in the had warned the War Cabinet in London that shipping nearest shell hole and covered ourselves with losses caused by German U-Boats were so great that a groundsheet, hoping for some sort of comfort Britain might not be able to continue fighting into 1918. out of the rain, and partly believed the sheet would also protect us from the rain of shells. -

The Fallen of Embleton Chapter 4 – 1917

[1] The Fallen of Embleton Chapter 4 – 1917 A tribute to the men of Embleton who fell in the Great War Written and researched by Terry Howells Mary Kibble Monica Cornall [2] Chapter 4 1917 Despite the results, or rather the lack of results, of the 1916 fighting the Allies decided to continue with their great offensives into 1917. The Russians would attack at both ends of their front whilst the Italians would continue to campaign on the Isonzo, the French would seize the Chemin des Dames and the British would push out from the Arras area. Meanwhile the Germans looked to strengthen their positions, but had no plans to attack the Russians. In France they undertook a withdrawal to their Hindenburg Line, giving up territory they had defended fiercely during the battle of the Somme and destroying everything useful in their wake. This was a strong defensive line running from Arras to Soisson (110 miles, 180 km) featuring a series of strongly fortified positions. It lay some 15 miles to their rear and was heavily protected by artillery. In March the Russian revolution broke out, destroying any hope of a spring offensive on the eastern front. The British were now the first to attack as part of the Allied spring offensive. Their First Army was tasked with seizing Vimy Ridge to protect the flank of the Third Army, which was to break through the Hindenburg Line. Vimy Ridge was captured on April 9th, the attack being supported by a British offensive from Arras. The Third Army advanced for over a mile across its whole front but then stalled due to logistical problems. -

Newsletter Feb 2018 PDF.Pdf

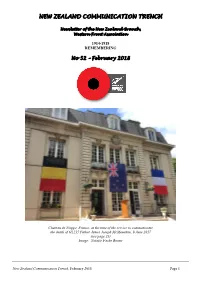

NEW ZEALAND COMMUNICATION TRENCH Newsletter of the New Zealand Branch, Western Front Association 1914-1918 REMEMBERING No 52 – February 2018 Chateau de Nieppe, France, at the time of the service to commemorate the death of 6/1215 Father James Joseph McMenamin, 8 June 2017 (see page 23) Image: Natalie Fache Boone New Zealand Communication Trench, February 2018 Page 1 ww100 theme for 2018: The Darkness Before the Dawn. By year’s end 1918, hostilities were over and the Allies had secured victory. Commemoration of the Liberation of Le Quesnoy 4 November 2018 Notes from the editor Thank you to all the people who have contributed to the newsletter: from New Zealand, Australia, the UK, and Belgium. This newsletter wouldn’t have been possible without your contributions and to each and every one of you, a very big thank you. Thank you also to Geoff McMillan and Paul Simadas for their help with some proof-reading. It’s a small world … three people with connections to the New Zealand Branch quite coincidentally were on the same tour of the battlefields in Israel in November 2017: Paul Simadas (chairman of the Australian Branch), Gary Murdoch (New Zealand Branch member from Wellington), and Edward Holman (who had contacted me earlier in the year about photos of VC graves and headstones). These men must have had a fantastic trip and Paul and Gary have shared their experiences with us. I couldn’t find appropriate photos on the internet showing the New Zealand silhouette recently unveiled at the Scottish Memorial in Zonnebeke, so a call for help to Richard Pursehouse sent him on a mission contacting his friends on Facebook. -

Armistice of November 1918: Centenary Table of Contents Debate on 5 November 2018 1

Armistice of November 1918: Centenary Table of Contents Debate on 5 November 2018 1. Events Leading to the Armistice of November 1918 Summary 2. Armistice of November 1918 This House of Lords Library Briefing has been prepared in advance of the debate due to take place on 5 November 2018 in the House of Lords on the 3. Centenary motion moved by Lord Ashton of Hyde (Conservative), “that this House takes Commemorations of the note of the centenary of the armistice at the end of the First World War”. Armistice in the UK On 11 November 1918, an armistice between the Allied Powers and Germany was signed, ending the fighting on the western front during the First World War. The armistice was signed at 5am in a French railway carriage in Compiègne, and the guns stopped firing six hours later, at 11am. Under the terms of the armistice, Germany was to relinquish all the territory it had conquered since 1914, as well as Alsace-Lorraine. The Rhineland would be demilitarised, and the German fleet was to be interned in harbours of neutral countries or handed to the British. Announcing the terms in the House of Commons, the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, expressed relief at the “end[ing of] the cruellest and most terrible war that has ever scourged mankind”. The centenary of the signing of the armistice will be marked on 11 November 2018 by a series of events. The traditional national service of remembrance at the Cenotaph will take place, as well as the Royal British Legion’s veteran dispersal and march past the Cenotaph.