Spindle Shaped Virus (SSV) : Mutants and Their Infectivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bacteriophage of Enterococcus Species for Microbial Source Tracking

Bacteriophage of Enterococcus species for microbial source tracking Sarah Elizabeth Purnell A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2012 School of Environment and Technology University of Brighton United Kingdom Abstract Contamination of surface waters with faeces may lead to increased public risk of human exposure to pathogens through drinking water supply, aquaculture, and recreational activities. Determining the source(s) of contamination is important for assessing the degree of risk to public health, and for selecting appropriate mitigation measures. Phage-based microbial source tracking (MST) techniques have been promoted as effective, simple and low-cost. The intestinal enterococci are a faecal “indicator of choice” in many parts of the world for determining water quality, and recently, phages capable of infecting Enterococcus faecalis have been proposed as a potential alternative indicator of human faecal contamination. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate critically the suitability and efficacy of phages infecting host strains of Enterococcus species as a low-cost tool for MST. In total, 390 potential Enterococcus hosts were screened for their ability to detect phage in reference faecal samples. Development and implementation of a tiered screening approach allowed the initial large number of enterococcal hosts to be reduced rapidly to a smaller subgroup suitable for phage enumeration and MST. Twenty-nine hosts were further tested using additional faecal samples of human and non-human origin. Their specificity and sensitivity were found to vary, ranging from 44 to 100% and from 17 to 83%, respectively. Most notably, seven strains exhibited 100% specificity to cattle, human, or pig samples. -

Novel Sulfolobus Virus with an Exceptional Capsid Architecture

GENETIC DIVERSITY AND EVOLUTION crossm Novel Sulfolobus Virus with an Exceptional Capsid Architecture Haina Wang,a Zhenqian Guo,b Hongli Feng,b Yufei Chen,c Xiuqiang Chen,a Zhimeng Li,a Walter Hernández-Ascencio,d Xin Dai,a,f Zhenfeng Zhang,a Xiaowei Zheng,a Marielos Mora-López,d Yu Fu,a Chuanlun Zhang,e Ping Zhu,b,f Li Huanga,f aState Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China bNational Laboratory of Biomacromolecules, CAS Center for Excellence in Biomacromolecules, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China cState Key Laboratory of Marine Geology, Tongji University, Shanghai, China dCenter for Research in Cell and Molecular Biology, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica eDepartment of Ocean Science and Engineering, South University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China fCollege of Life Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China ABSTRACT A novel archaeal virus, denoted Sulfolobus ellipsoid virus 1 (SEV1), was isolated from an acidic hot spring in Costa Rica. The morphologically unique virion of SEV1 contains a protein capsid with 16 regularly spaced striations and an 11-nm- thick envelope. The capsid exhibits an unusual architecture in which the viral DNA, probably in the form of a nucleoprotein filament, wraps around the longitudinal axis of the virion in a plane to form a multilayered disk-like structure with a central hole, and 16 of these structures are stacked to generate a spool-like capsid. SEV1 harbors a linear double-stranded DNA genome of ϳ23 kb, which encodes 38 predicted open reading frames (ORFs). -

Phylogenetics of Archaeal Lipids Amy Kelly 9/27/2006 Outline

Phylogenetics of Archaeal Lipids Amy Kelly 9/27/2006 Outline • Phlogenetics of Archaea • Phlogenetics of archaeal lipids • Papers Phyla • Two? main phyla – Euryarchaeota • Methanogens • Extreme halophiles • Extreme thermophiles • Sulfate-reducing – Crenarchaeota • Extreme thermophiles – Korarchaeota? • Hyperthermophiles • indicated only by environmental DNA sequences – Nanoarchaeum? • N. equitans a fast evolving euryarchaeal lineage, not novel, early diverging archaeal phylum – Ancient archael group? • In deepest brances of Crenarchaea? Euryarchaea? Archaeal Lipids • Methanogens – Di- and tetra-ethers of glycerol and isoprenoid alcohols – Core mostly archaeol or caldarchaeol – Core sometimes sn-2- or Images removed due to sn-3-hydroxyarchaeol or copyright considerations. macrocyclic archaeol –PMI • Halophiles – Similar to methanogens – Exclusively synthesize bacterioruberin • Marine Crenarchaea Depositional Archaeal Lipids Biological Origin Environment Crocetane methanotrophs? methane seeps? methanogens, PMI (2,6,10,15,19-pentamethylicosane) methanotrophs hypersaline, anoxic Squalane hypersaline? C31-C40 head-to-head isoprenoids Smit & Mushegian • “Lost” enzymes of MVA pathway must exist – Phosphomevalonate kinase (PMK) – Diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase – Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase (IPPI) Kaneda et al. 2001 Rohdich et al. 2001 Boucher et al. • Isoprenoid biosynthesis of archaea evolved through a combination of processes – Co-option of ancestral enzymes – Modification of enzymatic specificity – Orthologous and non-orthologous gene -

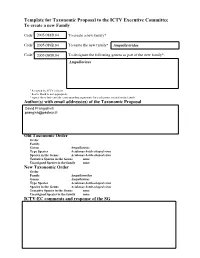

Template for Taxonomic Proposal to the ICTV Executive Committee to Create a New Family

Template for Taxonomic Proposal to the ICTV Executive Committee To create a new Family Code† 2005.088B.04 To create a new family* Code† 2005.089B.04 To name the new family* Ampullaviridae † Code 2005.090B.04 To designate the following genera as part of the new family*: Ampullavirus † Assigned by ICTV officers ° Leave blank is not appropriate * repeat these lines and the corresponding arguments for each genus created in the family Author(s) with email address(es) of the Taxonomic Proposal David Prangishvili [email protected] Old Taxonomic Order Order Family Genus Ampullavirus Type Species Acidianus bottle-shaped virus Species in the Genus Acidianus bottle-shaped virus Tentative Species in the Genus none Unassigned Species in the family none New Taxonomic Order Order Family Ampullaviridae Genus Ampullavirus Type Species Acidianus bottle-shaped virus Species in the Genus Acidianus bottle-shaped virus Tentative Species in the Genus none Unassigned Species in the family none ICTV-EC comments and response of the SG Argumentation to create a new family: We propose classifying the Acidianus bottle-shaped virus as a first representative of a new family because of the unique bottle-shaped morphology of the virion which, to our knowledge, has not previously been observed in the viral world. Moreover, the complex asymmetric virion, lacking elements with icosahedral or regular helical symmetry, with two completely different structures at each end and an envelope encasing a funnel-shaped core represents, as far as we can judge, represents a principally novel type of virus particle. The funnel-shaped core of the enveloped virion consists of three distinct structural units: the “stopper”, the nucleoprotein cone, consisting of double-stranded DNA and DNA-binding proteins, and the inner core. -

The LUCA and Its Complex Virome in Another Recent Synthesis, We Examined the Origins of the Replication and Structural Mart Krupovic , Valerian V

PERSPECTIVES archaea that form several distinct, seemingly unrelated groups16–18. The LUCA and its complex virome In another recent synthesis, we examined the origins of the replication and structural Mart Krupovic , Valerian V. Dolja and Eugene V. Koonin modules of viruses and posited a ‘chimeric’ scenario of virus evolution19. Under this Abstract | The last universal cellular ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population model, the replication machineries of each of of organisms from which all cellular life on Earth descends. The reconstruction of the four realms derive from the primordial the genome and phenotype of the LUCA is a major challenge in evolutionary pool of genetic elements, whereas the major biology. Given that all life forms are associated with viruses and/or other mobile virion structural proteins were acquired genetic elements, there is no doubt that the LUCA was a host to viruses. Here, by from cellular hosts at different stages of evolution giving rise to bona fide viruses. projecting back in time using the extant distribution of viruses across the two In this Perspective article, we combine primary domains of life, bacteria and archaea, and tracing the evolutionary this recent work with observations on the histories of some key virus genes, we attempt a reconstruction of the LUCA virome. host ranges of viruses in each of the four Even a conservative version of this reconstruction suggests a remarkably complex realms, along with deeper reconstructions virome that already included the main groups of extant viruses of bacteria and of virus evolution, to tentatively infer archaea. We further present evidence of extensive virus evolution antedating the the composition of the virome of the last universal cellular ancestor (LUCA; also LUCA. -

On the Biological Success of Viruses

MI67CH25-Turner ARI 19 June 2013 8:14 V I E E W R S Review in Advance first posted online on June 28, 2013. (Changes may still occur before final publication E online and in print.) I N C N A D V A On the Biological Success of Viruses Brian R. Wasik and Paul E. Turner Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8106; email: [email protected], [email protected] Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013. 67:519–41 Keywords The Annual Review of Microbiology is online at adaptation, biodiversity, environmental change, evolvability, extinction, micro.annualreviews.org robustness This article’s doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102833 Abstract Copyright c 2013 by Annual Reviews. Are viruses more biologically successful than cellular life? Here we exam- All rights reserved ine many ways of gauging biological success, including numerical abun- dance, environmental tolerance, type biodiversity, reproductive potential, and widespread impact on other organisms. We especially focus on suc- cessful ability to evolutionarily adapt in the face of environmental change. Viruses are often challenged by dynamic environments, such as host immune function and evolved resistance as well as abiotic fluctuations in temperature, moisture, and other stressors that reduce virion stability. Despite these chal- lenges, our experimental evolution studies show that viruses can often readily adapt, and novel virus emergence in humans and other hosts is increasingly problematic. We additionally consider whether viruses are advantaged in evolvability—the capacity to evolve—and in avoidance of extinction. On the basis of these different ways of gauging biological success, we conclude that viruses are the most successful inhabitants of the biosphere. -

Viruses in a 14Th-Century Coprolite

AEM Accepts, published online ahead of print on 7 February 2014 Appl. Environ. Microbiol. doi:10.1128/AEM.03242-13 Copyright © 2014, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. 1 Title: Viruses in a 14th-century coprolite 2 Running title: Viruses in a 14th-century coprolite 3 4 Sandra Appelt1,*, Laura Fancello1,*, Matthieu Le Bailly2, Didier Raoult1, Michel Drancourt1, 5 Christelle Desnues†,1 6 7 1 Aix Marseille Université, URMITE, UM63, CNRS 7278, IRD 198, Inserm 1095, 13385 8 Marseille, France. 9 2 Franche-Comté University, CNRS UMR 6249 Chrono-Environment, 25 030 Besançon, France. 10 * These authors have contributed equally to this work 11 † Corresponding author: 12 Christelle Desnues, Unité de recherche sur les maladies infectieuses et tropicales émergentes 13 (URMITE), UM63, CNRS 7278, IRD 198, Inserm 1095, Faculté de médecine, Aix Marseille 14 Université, 27 Bd Jean Moulin, 13385 Marseille, France. Tel: (+33) 4 91 38 46 30, Fax: (+33) 4 15 91 38 77 72. 16 Email: [email protected] 17 Number of words in Abstract: 133 words 18 Number of words in Main Text: 2538 words 19 Number of words in Methods: 954 words 20 Figures: 4, Supplementary Figures: 3 21 Tables: 0, Supplementary Tables: 6 22 Keywords: coprolite, paleomicrobiology, metagenomics, bacteriophages, viruses, ancient DNA 1 23 Abstract 24 Coprolites are fossilized fecal material that can reveal information about ancient intestinal and 25 environmental microbiota. Viral metagenomics has allowed systematic characterization of viral 26 diversity in environmental and human-associated specimens, but little is known about the viral 27 diversity in fossil remains. Here, we analyzed the viral community of a 14th-century coprolite 28 from a closed barrel in a Middle Age site in Belgium using electron microscopy and 29 metagenomics. -

Viruses of Hyperthermophilic Archaea: Entry and Egress from the Host Cell

Viruses of hyperthermophilic archaea : entry and egress from the host cell Emmanuelle Quemin To cite this version: Emmanuelle Quemin. Viruses of hyperthermophilic archaea : entry and egress from the host cell. Microbiology and Parasitology. Université Pierre et Marie Curie - Paris VI, 2015. English. NNT : 2015PA066329. tel-01374196 HAL Id: tel-01374196 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01374196 Submitted on 30 Sep 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Pierre et Marie Curie – Paris VI Unité de Biologie Moléculaire du Gène chez les Extrêmophiles Ecole doctorale Complexité du Vivant ED515 Département de Microbiologie - Institut Pasteur 7, quai Saint-Bernard, case 32 25, rue du Dr. Roux 75252 Paris Cedex 05 75015 Paris THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PIERRE ET MARIE CURIE Spécialité : Microbiologie Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE PIERRE ET MARIE CURIE VIRUSES OF HYPERTHERMOPHILIC ARCHAEA: ENTRY INTO AND EGRESS FROM THE HOST CELL Présentée par M. Emmanuelle Quemin Soutenue le 28 Septembre 2015 devant le jury composé de : Prof. Guennadi Sezonov Président du jury Prof. Christa Schleper Rapporteur de thèse Dr. Paulo Tavares Rapporteur de thèse Dr. -

WO 2015/061752 Al 30 April 2015 (30.04.2015) P O P CT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2015/061752 Al 30 April 2015 (30.04.2015) P O P CT (51) International Patent Classification: Idit; 816 Fremont Street, Apt. D, Menlo Park, CA 94025 A61K 39/395 (2006.01) A61P 35/00 (2006.01) (US). A61K 31/519 (2006.01) (74) Agent: HOSTETLER, Michael, J.; Wilson Sonsini (21) International Application Number: Goodrich & Rosati, 650 Page Mill Road, Palo Alto, CA PCT/US20 14/062278 94304 (US). (22) International Filing Date: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 24 October 2014 (24.10.2014) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (25) Filing Language: English BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, (26) Publication Language: English DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, (30) Priority Data: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, 61/895,988 25 October 2013 (25. 10.2013) US MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, 61/899,764 4 November 2013 (04. 11.2013) US PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, 61/91 1,953 4 December 2013 (04. 12.2013) us SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 61/937,392 7 February 2014 (07.02.2014) us TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Sulfolobus As a Model Organism for the Study of Diverse

SULFOLOBUS AS A MODEL ORGANISM FOR THE STUDY OF DIVERSE BIOLOGICAL INTERESTS; FORAYS INTO THERMAL VIROLOGY AND OXIDATIVE STRESS by Blake Alan Wiedenheft A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Microbiology MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana November 2006 © COPYRIGHT by Blake Alan Wiedenheft 2006 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a dissertation submitted by Blake Alan Wiedenheft This dissertation has been read by each member of the dissertation committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Mark Young and Dr. Trevor Douglas Approved for the Department of Microbiology Dr.Tim Ford Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a doctoral degree at Montana State University – Bozeman, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. I further agree that copying of this dissertation is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for extensive copying or reproduction of this dissertation should be referred to ProQuest Information and Learning, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106, to whom I have granted “the exclusive right to reproduce and distribute my dissertation in and from microfilm along with the non-exclusive right to reproduce and distribute my abstract in any format in whole or in part.” Blake Alan Wiedenheft November, 2006 iv DEDICATION This work was funded in part through grants from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Program (NAG5-8807) in support of Montana State University’s Center for Life in Extreme Environments (MCB-0132156), and the National Institutes of Health (R01 EB00432 and DK57776). -

Sp. Nov. and Acidianus Brierleyi Comb

INTERNATIONALJOURNAL OF SYSTEMATICBACTERIOLOGY, Oct. 1986, p. 559-564 Vol. 36, No. 4 0020-7713/86/040559-06$02.OO/O Copyright 0 1986, International Union of Microbiological Societies Acidianus infernus gen. nov.? sp. nov. and Acidianus brierleyi comb. nov. : Facultatively Aerobic, Extremely Acidophilic Thermophilic Sulfur-Metabolizing Archaebacteria ANDREAS SEGERER,l ANNEMARIE NEUNER,I JAKOB K. KRISTJANSSON,2 AND KARL 0. STETTER1* Lehrstuhl fur Mikrobiologie, Universitat, 8400 Regensburg, Federal Republic of Germany' and Institute of Biology, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Icelana A new genus, Acidianus, is characterized from studies of 26 isolates of thermoacidophilic archaebacteria from different solfatara fields and marine hydrothermal systems; these isolates grow as facultative aerobes by lithotrophic oxidation and reduction of So, respectively, and are therefore different from the strictly aerobic Sulfolobus species. The Acidianus isolates have a deoxyribonucleic acid guanine-plus-cytosinecontent of 31 mol%. In contrast, two of three Sulfolobus species, including the type species, have a guanine-plus-cytosine content of 37 mol%; Sulfolobus brierleyi is the exception, with a guanine-plus-cytosine content of 31 mol%. In contrast to its earlier descriptions, S. brierleyi is able to grow strictly anaerobically by hydrogen-sulfur autotrophy. Therefore, it is described here as a member of the genus Acidiunus. The following species are assigned to the genus Acidiunus: Acidiunus infernus sp. nov. (type strain, strain DSM 3191) and Acidiunus brierleyi comb. nov. (type strain, strain DSM 1651). The following two major groups of extremely thermophilic MATERIALS AND METHODS So-metabolizing archaebacteria (12) that thrive within acidic solfatara fields have been described previously: (i) the genus Bacterial strains. -

2018-2019 Update from the ICTV Bacterial and Archaeal Viruses

Archives of Virology (2020) 165:1253–1260 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-020-04577-8 VIROLOGY DIVISION NEWS: Taxonomy of prokaryotic viruses: 2018‑2019 update from the ICTV Bacterial and Archaeal Viruses Subcommittee Evelien M. Adriaenssens1 · Matthew B. Sullivan2 · Petar Knezevic3 · Leonardo J. van Zyl4 · B. L. Sarkar5 · Bas E. Dutilh6,7 · Poliane Alfenas‑Zerbini8 · Małgorzata Łobocka9 · Yigang Tong10 · James Rodney Brister11 · Andrea I. Moreno Switt12 · Jochen Klumpp13 · Ramy Karam Aziz14 · Jakub Barylski15 · Jumpei Uchiyama16 · Rob A. Edwards17,18 · Andrew M. Kropinski19,20 · Nicola K. Petty21 · Martha R. J. Clokie22 · Alla I. Kushkina23 · Vera V. Morozova24 · Siobain Dufy25 · Annika Gillis26 · Janis Rumnieks27 · İpek Kurtböke28 · Nina Chanishvili29 · Lawrence Goodridge19 · Johannes Wittmann30 · Rob Lavigne31 · Ho Bin Jang32 · David Prangishvili33,34 · Francois Enault35 · Dann Turner36 · Minna M. Poranen37 · Hanna M. Oksanen37 · Mart Krupovic33 Published online: 11 March 2020 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Austria, part of Springer Nature 2020 Abstract This article is a summary of the activities of the ICTV’s Bacterial and Archaeal Viruses Subcommittee for the years 2018 and 2019. Highlights include the creation of a new order, 10 families, 22 subfamilies, 424 genera and 964 species. Some of our concerns about the ICTV’s ability to adjust to and incorporate new DNA- and protein-based taxonomic tools are discussed. Introduction Taxonomic updates The prokaryotic virus community is represented in the Inter- Over the past two years, our subcommittee