Articles and Letters to Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moderating the Mormon Discourse on Modesty

PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF MORMON WOMEN SINCE 1974 EXPONENT II Am I Not a Woman and a Sister? MODERATING THE MODERN DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Jennifer Finlayson-Fife SISTERS SPEAK: THOUGHTS ON MOTHERS’ BLESSINGS VOL. 33 | NO. 3 | WINTER 2014 04 PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF 18 Mormon Women SINCE 1974 14 16 WHAT IS EXPONENT II ? The purpose of Exponent II is to provide a forum for Mormon women to share their life 34 experiences in an atmosphere of trust and acceptance. This exchange allows us to better understand each other and shape the direction of our lives. Our common bond is our connection to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and our commitment to 24 women. We publish this paper as a living history in celebration of the strength and diversity 30 of women. 36 FEATURED STORIES ADDITIONAL FEATURES 03 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 24 FLANNEL BOARD New Recruits in the Armies of Shelaman: Notes from a Primary Man MODERATING THE 04 AWAKENINGS Rob McFarland Making Peace with Mystery: To Prophet Jonah MORMON DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Mary B. Johnston 28 Reflections on a Wedding BY JENNIFER FINLAYSON-FIFE, WILMETTE, ILLINOIS Averyl Dietering 07 SISTERS SPEAK ON THE COVER: I believe the LDS cultural discourse around modesty is important because Sharing Experiences with Mothers’ Blessings 30 SABBATH PASTORALS Page Turner of its very real implications for women in the Church. How we construct Being Grateful for God’s Hand in a World I our sexuality deeply affects how we relate to ourselves and to one another. Moderating the Mormon Discourse on -

Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects by Eugene England

Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects By Eugene England This essay is the culmination of several attempts England made throughout his life to assess the state of Mormon literature and letters. The version below, a slightly revised and updated version of the one that appeared in David J. Whittaker, ed., Mormon Americana: A Guide to Sources and Collections in the United States (Provo, Utah: BYU Studies, 1995), 455–505, is the one that appeared in the tribute issue Irreantum published following England’s death. Originally published in: Irreantum 3, no. 3 (Autumn 2001): 67–93. This, the single most comprehensive essay on the history and theory of Mormon literature, first appeared in 1982 and has been republished and expanded several times in keeping up with developments in Mormon letters and Eugene England’s own thinking. Anyone seriously interested in LDS literature could not do better than to use this visionary and bibliographic essay as their curriculum. 1 ExpEctations MorMonisM hAs bEEn called a “new religious tradition,” in some respects as different from traditional Christianity as the religion of Jesus was from traditional Judaism. 2 its beginnings in appearances by God, Jesus Christ, and ancient prophets to Joseph smith and in the recovery of lost scriptures and the revelation of new ones; its dramatic history of persecution, a literal exodus to a promised land, and the build - ing of an impressive “empire” in the Great basin desert—all this has combined to make Mormons in some ways an ethnic people as well as a religious community. Mormon faith is grounded in literal theophanies, concrete historical experience, and tangible artifacts (including the book of Mormon, the irrigated fields of the Wasatch Front, and the great stone pioneer temples of Utah) in certain ways that make Mormons more like ancient Jews and early Christians and Muslims than, say, baptists or Lutherans. -

Worth Their Salt, Too

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 Worth Their Salt, Too Colleen Whitley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Whitley, C. (2000). Worth their salt, too: More notable but often unnoted women of Utah. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Worth Their Salt, Too More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah WORTH THEIR SALT, TOO More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah Edited by Colleen Whitley UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2000 Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press “Marion Davis Clegg: The Lady of the Lakes” copyright © 2000 Carol C. Johnson All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 All royalties from the sale of this book will be donated to support the Exhibits office of the Utah State Historical Society. Cover photos: Marion Davis Clegg, courtesy of Photosynthesis; Verla Gean FarmanFarmaian, courtesy of Gean FarmanFarmaian; Ora Bailey Harding, courtesy of Lurean S. Harding; Alberta Henry, courtesy of the Deseret News; Esther Peterson, courtesy of Paul A. Allred; Virginia Sorensen, courtesy of Mary Bradford Typography by WolfPack Printed in Canada Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Worth their salt, too : more notable but often unnoted women of Utah / edited by Colleen Whitley. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999

Journal of Mormon History Volume 25 Issue 1 Article 1 1999 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1999) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 25 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999 Table of Contents CONTENTS --In Memoriam: Leonard J. Arrington, 5 --Remembering Leonard: Memorial Service, 10 --15 February, 1999 --The Voices of Memory, 33 --Documents and Dusty Tomes: The Adventure of Arrington, Esplin, and Young Ronald K. Esplin, 103 --Mormonism's "Happy Warrior": Appreciating Leonard J. Arrington Ronald W.Walker, 113 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --In Search of Ephraim: Traditional Mormon Conceptions of Lineage and Race Armand L. Mauss, 131 TANNER LECTURE • --Extracting Social Scientific Models from Mormon History Rodney Stark, 174 • --Gathering and Election: Israelite Descent and Universalism in Mormon Discourse Arnold H. Green, 195 • --Writing "Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview" (1973): Context and Reflections, 1998 Lester Bush, 229 • --"Do Not Lecture the Brethren": Stewart L. Udall's Pro-Civil Rights Stance, 1967 F. Ross Peterson, 272 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss1/ 1 JOURNAL OF MORMON HISTORY SPRING 1999 JOURNAL OF MORMON HISTORY SPRING 1999 Staff of the Journal of Mormon History Editorial Staff Editor: Lavina Fielding Anderson Executive Committee: Lavina Fielding Anderson, Will Bagley, William G. -

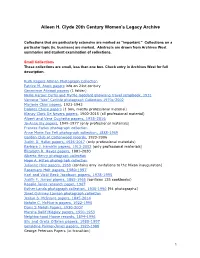

Clyde Archive Finding

Aileen H. Clyde 20th Century Women's Legacy Archive Collections that are particularly extensive are marked as “important.” Collections on a particular topic (ie. business) are marked. Abstracts are drawn from Archives West summaries and student examination of collections. Small Collections These collections are small, less than one box. Check entry in Archives West for full description. Ruth Rogers Altman Photograph Collection Patrice M. Arent papers info on 21st century Genevieve Atwood papers (1 folder) Nellie Harper Curtis and Myrtle Goddard Browning travel scrapbook, 1931 Vervene “Vee” Carlisle photograph Collection 1970s-2002 Marjorie Chan papers, 1921-1943 Dolores Chase papers (1 box, mostly professional material) Klancy Clark De Nevers papers, 1900-2015 (all professional material) Albert and Vera Cuglietta papers, 1935-2016 Jo-Anne Ely papers, 1949-1977 (only professional materials) Frances Farley photograph collection Anne Marie Fox Felt photograph collection, 1888-1969 Garden Club of Cottonwood records, 1923-2006 Judith D. Hallet papers, 1926-2017 (only professional materials) Barbara J. Hamblin papers, 1913-2003 (only professional materials) Elizabeth R. Hayes papers, 1881-2020 Alberta Henry photograph collection Hope A. Hilton photograph collection Julianne Hinz papers, 1969 (contains only invitations to the Nixon inauguration) Rosemary Holt papers, 1980-1997 Karl and Vicki Beck Jacobson papers, 1978-1995 Judith F. Jarrow papers, 1865-1965 (contains 135 cookbooks) Rosalie Jones research paper, 1967 Esther Landa photograph collection, 1930-1990 [94 photographs] Janet Quinney Lawson photograph collection Jerilyn S. McIntyre papers, 1845-2014 Natalie C. McMurrin papers, 1922-1995 Doris S Melich Papers, 1930-2007 Marsha Ballif Midgley papers, 1950-1953 Neighborhood House records, 1894-1996 Stu and Greta O’Brien papers, 1980-1997 Geraldine Palmer-Jones papers, 1922-1988 George Peterson Papers (in transition) 1 Ann Pingree Collection, 2011 Charlotte A. -

Full Issue BYU Studies

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 53 | Issue 3 Article 1 9-1-2014 Full Issue BYU Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Studies, BYU (2014) "Full Issue," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 53 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol53/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Advisory Board Alan L. Wilkins, chairStudies: Full Issue James P. Bell Donna Lee Bowen Douglas M. Chabries Doris R. Dant R. Kelly Haws Editor in Chief John W. Welch Church History Board Richard Bennett, chair 19th-century history Brian Q. Cannon 20th-century history Kathryn Daynes 19th-century history Gerrit J. Dirkmaat Involving Readers Joseph Smith, 19th-century Mormonism Steven C. Harper in the Latter-day Saint documents Academic Experience Frederick G. Williams cultural history Liberal Arts and Sciences Board Barry R. Bickmore, co-chair geochemistry Eric Eliason, co-chair English, folklore David C. Dollahite faith and family life Susan Howe English, poetry, drama Neal Kramer early British literature, Mormon studies Steven C. Walker Christian literature Reviews Board Eric Eliason, co-chair English, folklore John M. Murphy, co-chair Mormon and Western Trevor Alvord new media Herman du Toit art, museums Angela Hallstrom literature Greg Hansen music Emily Jensen new media Megan Sanborn Jones theater and media arts Gerrit van Dyk Church history Specialists Casualene Meyer poetry editor Thomas R. -

Notes from a Mormon Poet

Tschanz Rare Books List 20! Usual terms (we’re a reasonable lot – what do you need?) Call: 801-641-2874 Or email: [email protected] to confirm availability. (it’s all the same to us) Domestic shipping: $10 International and overnight shipping billed at cost. Schmancy New Website! www.tschanzrarebooks.com Exceptional Copy in Deluxe Binding 1- Smith, Joseph. The Book of Mormon: An Account Written by the Hand of Mormon, Upon Plates Taken from the Plates of Nephi. Liverpool: Published by F.D. Richards, 1854. Fifth Edition. 563pp. Duodecimo [15 cm] Fine. Full black grained morocco with a gilt rectangular panel surrounded by a gilt vine like figure inside a gilt ruled border in blind on the board. Decorative floral gilt stamping to the backstrip with the title gilt stamped. Gilt dentelles. A.E.G. Decorative endsheets. Fine. An exceptionally nice copy of this work. When Franklin D. Richards succeeded his brother Samuel as the British Mission President on June 30, 1854, the Liverpool office had 540 copies of the 1852 Book of Mormon in its inventory, the entire fourth edition having been shipped to Salt Lake City in March of the same year. Almost three months later the Millennial Star noted that the fourth edition was out of print, but another edition would "shortly be ready," and on November 11 the Millennial Star had an advertisement of "A List of Books for Sale" that listed the fifth edition available in sheep, calf or morocco. 2,975 copies were printed, 100 copies were bound in the deluxe binding. Crawley 928. -

Mormon Feminism and Prospects for Change in the LDS Church Holly Theresa Bignall Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2010 Hope deferred: Mormon feminism and prospects for change in the LDS church Holly Theresa Bignall Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bignall, Holly Theresa, "Hope deferred: Mormon feminism and prospects for change in the LDS church" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 11699. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/11699 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hope deferred: Mormon feminism and prospects for change in the LDS church by Holly Theresa Bignall A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: Interdisciplinary Graduate Studies (Arts and Humanities) Program of Study Committee: Nikki Bado, Major Professor Heimir Geirsson Chrisy Moutsatsos Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2010 Copyright © Holly Theresa Bignall, 2010. All rights reserved. ii What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore-- And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over-- like a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode? Langston Hughes, Montage of a Dream Deferred iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v ABSTRACT vi CHAPTER 1 – REFLEXIVITY AND THE LATTER-DAY SAINT TRADITION 1 1.a. -

AML 2004 Annual

Annual of the Association for Mormon Letters 2004 Association for Mormon Letters Provo, Utah © 2004 by the Association for Mormon Letters. After publi- cation herein, all rights revert to the authors. The Association for Mormon Letters assumes no responsibility for contri- butors’ statements of fact or opinion. Editor: Linda Hunter Adams Production Director: Marny K. Parkin Staff: Robert Cunningham Marshelle Mason Papa Jena Peterson Amanda Riddle Jared Salter Erin Saunders Anna Swallow Jodi Traveller The Association for Mormon Letters P.O. Box 51364 Provo, UT 84605-1364 (801) 714-1326 [email protected] www.aml-online.org Note: An AML order form appears at the end of this volume. Contents Presidential Address Our Mormon Renaissance Gideon O. Burton 1 Friday Sessions Keynote Address The Place of Knowing Emma Lou Thayne 9 The Tragedy of Brigham City: How a Film about Morality Becomes Immoral Michael Minch 23 The Novelization of Brigham City: An Odyssey Marilyn Brown 29 Pious Poisonings and Saintly Slayings: Creating a Mormon Murder Mystery Genre Lavina Fielding Anderson 35 Murder Most Mormon: Swelling the National Trend (Part II) Conspiring to Commit Paul M. Edwards, read by Tom Kimball 39 God and Man in The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint Bradley D. Woodworth 43 Brady Udall, the Smart-Ass Deacon Mary L. Bingham Lee 47 Egypt and Israel versus Germany and Jews: Comparing Margaret Blair Young’s House without Walls to the Bible Nichole Sutherland 53 iii AML Annual 2004 Stone Tables: Believable Characters in Orson Scott Card’s Historical Fiction -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 27, No. 2, 2001

Journal of Mormon History Volume 27 Issue 2 Article 1 2001 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 27, No. 2, 2001 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2001) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 27, No. 2, 2001," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 27 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol27/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 27, No. 2, 2001 Table of Contents CONTENTS LETTERS vii ARTICLES • --Polygamy and Prostitution: Comparative Morality in Salt Lake City, 1847-1911 Jeffrey D. Nichols, 1 • --"Called by a New Name": Mission, Identity, and the Reorganized Church Mark A. Scherer, 40 • --Samuel Woolley Taylor: Mormon Maverick Historian Richard H. Cracroft, 64 • --Fish and the Famine of 1855-56 D. Robert Carter, 92 • --"As Ugly as Evil" and "As Wicked as Hell": Gadianton Robbers and the Legend Process among the Mormons W.Paul Reeve, 125 • --The East India Mission of 1851-1856: Crossing the Boundaries of Culture, Religion, and Law R. Lanier Britsch, 150 • --Steel Rails and the Utah Saints Richard O. Cowan, 177 • --"That Canny Scotsman": John Sharp and the Negotiations with the Union Pacific Railroad, 1869-1872 Craig L. Foster, 197 • --Charles S. Whitney: A Nineteenth-Century Salt Lake City Teenager's Life Kenneth W. -

Worth Their Salt, Too

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 Worth Their Salt, Too Colleen Whitley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Whitley, C. (2000). Worth their salt, too: More notable but often unnoted women of Utah. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Worth Their Salt, Too More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah WORTH THEIR SALT, TOO More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah Edited by Colleen Whitley UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2000 Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press “Marion Davis Clegg: The Lady of the Lakes” copyright © 2000 Carol C. Johnson All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 All royalties from the sale of this book will be donated to support the Exhibits office of the Utah State Historical Society. Cover photos: Marion Davis Clegg, courtesy of Photosynthesis; Verla Gean FarmanFarmaian, courtesy of Gean FarmanFarmaian; Ora Bailey Harding, courtesy of Lurean S. Harding; Alberta Henry, courtesy of the Deseret News; Esther Peterson, courtesy of Paul A. Allred; Virginia Sorensen, courtesy of Mary Bradford Typography by WolfPack Printed in Canada Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Worth their salt, too : more notable but often unnoted women of Utah / edited by Colleen Whitley. -

The Evolution of the Brigham Young University Women's Conference

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2006-03-21 From Womanhood to Sisterhood: The Evolution of the Brigham Young University Women's Conference Velda Gale Davis Lewis Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Lewis, Velda Gale Davis, "From Womanhood to Sisterhood: The Evolution of the Brigham Young University Women's Conference" (2006). Theses and Dissertations. 1081. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1081 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. FROM WOMANHOOD TO SISTERHOOD: THE EVOLUTION OF THE BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY WOMEN’S CONFERENCE by V. Gale Lewis A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History Brigham Young University April 2006 Copyright © V. Gale Lewis All Rights Reserved BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by V. Gale Lewis This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. ______________________________ ____________________________________ Date Richard I. Kimball, Chair ______________________________ ____________________________________