Tributaries to Totten Eld and Little Skookum Inlets Fecal Coliform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On-Site Sewage System Management Plan January 7, 2008

Thurston County Public Health and Social Services Department Environmental Health Division On-Site Sewage System Management Plan January 7, 2008 Thurston County On-site Sewage System Management Plan January 7, 2008 Table of Contents: Section Page Acknowledgements 3 Executive Summary 4 On-site Sewage System Management Plan 8 Part I – Database Enhancement 10 Part 2 – Identification of Sensitive Areas 16 Part 3 – Operation, Monitoring and Maintenance in Sensitive Areas 28 Part 4 – Marine Recovery and Sensitive Area Strategy 34 Part 5 – Education 39 Part 6 – Plan Summary 42 Appendices A – Amanda Reports 53 B – Henderson Watershed Protection Area Description 58 C – Process for Evaluation of Potential MRA’s and LMA’s 62 D – Marine Recovery Area and Local Management Area Designation Tool 63 E – Measurable Outcomes 70 F – Thurston County Septic Park 71 Page 2 of 71 Thurston County On-site Sewage System Management Plan January 7, 2008 Acknowledgements Thurston County Public Health and Social Services would like to acknowledge all those who have been instrumental in our process to develop our Local Management Plan (LMA). First of all we appreciate the contributions of the Article IV Advisory Committee in assisting the Environmental Health Division. Your dedication to providing direction and tone for the LMA has been invaluable. We would also like to recognize the Environmental Health, Development Services and Geodata staff for supplying input, recommendations and attending committee meetings to offer insight into our program areas. Our appreciation is also extended to the Washington State Department of Health. We are grateful for their staff support and funding. We especially appreciate the use of the guidance document, which has provided section descriptions and format for our plan. -

Chapter 13 -- Puget Sound, Washington

514 Puget Sound, Washington Volume 7 WK50/2011 123° 122°30' 18428 SKAGIT BAY STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA S A R A T O 18423 G A D A M DUNGENESS BAY I P 18464 R A A L S T S Y A G Port Townsend I E N L E T 18443 SEQUIM BAY 18473 DISCOVERY BAY 48° 48° 18471 D Everett N U O S 18444 N O I S S E S S O P 18458 18446 Y 18477 A 18447 B B L O A B K A Seattle W E D W A S H I N ELLIOTT BAY G 18445 T O L Bremerton Port Orchard N A N 18450 A 18452 C 47° 47° 30' 18449 30' D O O E A H S 18476 T P 18474 A S S A G E T E L N 18453 I E S C COMMENCEMENT BAY A A C R R I N L E Shelton T Tacoma 18457 Puyallup BUDD INLET Olympia 47° 18456 47° General Index of Chart Coverage in Chapter 13 (see catalog for complete coverage) 123° 122°30' WK50/2011 Chapter 13 Puget Sound, Washington 515 Puget Sound, Washington (1) This chapter describes Puget Sound and its nu- (6) Other services offered by the Marine Exchange in- merous inlets, bays, and passages, and the waters of clude a daily newsletter about future marine traffic in Hood Canal, Lake Union, and Lake Washington. Also the Puget Sound area, communication services, and a discussed are the ports of Seattle, Tacoma, Everett, and variety of coordinative and statistical information. -

South Puget Sound Forum Environmental Quality – Economic Vitality Indicators Report Updated July 2006

South Puget Sound Forum Environmental Quality – Economic Vitality Indicators Report Updated July 2006 Making connections and building partnerships to protect the marine waters, streams, and watersheds of Nisqually, Henderson, Budd, Eld and Totten Inlets The economic vitality of South Puget Sound is intricately linked to the environmental health of the Sound’s marine waters, streams, and watersheds. It’s hard to imagine the South Sound without annual events on or near the water - Harbor Days Tugboat Races, Wooden Boat Fair, Nisqually Watershed Festival, Swantown BoatSwap and Chowder Challenge, Parade of Lighted Ships – and other activities we prize such as beachcombing, boating, fishing, or simply enjoying a cool breeze at a favorite restaurant or park. South Sound is a haven for relaxation and recreation. Businesses such as shellfish growers and tribal fisheries, tourism, water recreational boating, marinas, port-related businesses, development and real estate all directly depend on the health of the South Sound. With strong contributions from the South Sound, statewide commercial harvest of shellfish draws in over 100 million dollars each year. Fishing, boating, travel and tourism are all vibrant elements in the region’s base economy, with over 80 percent of the state’s tourism and travel dollars generated in the Puget Sound Region. Many other businesses benefit indirectly. Excellent quality of life is an attractor for great employees, and the South Puget Sound has much to offer! The South Puget Sound Forum, held in Olympia on April 29, 2006, provided an opportunity to rediscover the connections between economic vitality and the health of South Puget Sound, and to take action to protect the valuable resources of the five inlets at the headwaters of the Puget Sound Basin – Totten, Eld, Budd, Henderson, and the Nisqually Reach. -

In the Eye of the European Beholder Maritime History of Olympia And

Number 3 August 2017 Olympia: In the Eye of the European Beholder Maritime History of Olympia and South Puget Sound Mining Coal: An Important Thurston County Industry 100 Years Ago $5.00 THURSTON COUNTY HISTORICAL JOURNAL The Thurston County Historical Journal is dedicated to recording and celebrating the history of Thurston County. The Journal is published by the Olympia Tumwater Foundation as a joint enterprise with the following entities: City of Lacey, City of Olympia, City of Tumwater, Daughters of the American Revolution, Daughters of the Pioneers of Washington/Olympia Chapter, Lacey Historical Society, Old Brewhouse Foundation, Olympia Historical Society and Bigelow House Museum, South Sound Maritime Heritage Association, Thurston County, Tumwater Historical Association, Yelm Prairie Historical Society, and individual donors. Publisher Editor Olympia Tumwater Foundation Karen L. Johnson John Freedman, Executive Director 360-890-2299 Katie Hurley, President, Board of Trustees [email protected] 110 Deschutes Parkway SW P.O. Box 4098 Editorial Committee Tumwater, Washington 98501 Drew W. Crooks 360-943-2550 Janine Gates James S. Hannum, M.D. Erin Quinn Valcho Submission Guidelines The Journal welcomes factual articles dealing with any aspect of Thurston County history. Please contact the editor before submitting an article to determine its suitability for publica- tion. Articles on previously unexplored topics, new interpretations of well-known topics, and personal recollections are preferred. Articles may range in length from 100 words to 10,000 words, and should include source notes and suggested illustrations. Submitted articles will be reviewed by the editorial committee and, if chosen for publication, will be fact-checked and may be edited for length and content. -

2000 Puget Sound Update Puget Sound Water Quality Action Team

2000 Puget Sound update Puget Sound Water Quality Action Team Seventh Report of the Puget Sound Ambient Monitoring Program March 2000 Puget Sound Water Quality Action Team P.O. Box 40900 Olympia,Washington 98504-0900 360/407-7300 or 800/54-SOUND http://www.wa.gov/puget_sound The Puget Sound Water Quality Action Team is an equal opportunity employer. If you have special accommodation needs, or need this document in an alternative format, please contact the Action Team’s ADA representative at (360) 407-7300. The Action Team’s TDD number is 1 (800) 833-6388. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is the product of the Puget Sound Ambient Monitoring Program and the Puget Sound Water Quality Action Team. Prepared by Action Team staff. Compiled and written by Scott Redman and Lori Scinto. Edited by Melissa Pearlman. Layout and graphics by Toni Weyman Droscher and Jill Williams. The PSAMP Steering and Management committees directed the development of this report. The members of these committees and the following people contributed material, comments and advice. Their contributions were essential to the development of this document. Shelly Ament, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife John Armstrong Ken Balcomb, Center for Whale Research Greg Bargmann, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Allison Beckett, Washington Department of Ecology John Calambokidis, Cascadia Research Collective Liz Carr, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Denise Clifford, Puget Sound Water Quality Action Team Wayne Clifford, Washington Department of Health Andrea -

Laura Johnson Office of Shellfish and Water Protection February 19, 2015

Laura Johnson Office of Shellfish and Water Protection February 19, 2015 Public Health – Always Working for a Safer and Healthier Washington 2014 Season • Vibrio parahaemolyticus Illnesses • Closures and time-to- temperature reductions • Environmental monitoring • Outreach • Other Vibrios Control Plan Rule Revision 2 Commercial shellstock oysters Non-commercial Single-source 26 Clams (geoduck and butter) 2 Multi-source 50 Crab 2 WA only 18 Oysters 8 WA and other states and provinces 32 Raw 5 Other commercial products Cooked 2 Shucked oysters 3 Both 1 Steamed clams 1 Salmon 1 Other Documented post harvest abuse 18 No traceback 7 3 Total Vibrio Illnesses from Oyster Consumption (Attributed to Washington State Growing Areas by Year) 120 100 80 60 Number of Number IIll ndividuals 40 20 0 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Year Single Source Multi Source Recreational 4 TTC Reduction Growing Area Harvest Reduction Date Hood Canal 6 5/28/2014 Oakland bay 7/25/2014 Samish Bay 7/25/2014 Henderson Inlet 7/29/2014 Totten Inlet 7/31/2014 Reach Island 7/31/2014 Hammersley Inlet 8/1/2014 Pickering Passage 8/4/2014 Hood Canal 7 8/5/2014 Nahcotta 8/7/2014 Grays Harbor 8/13/2014 Rocky Bay 8/13/2014 Rocky Bay 8/20/2014 Hood Canal 1 8/21/2014 Eld Inlet 8/27/2014 Skookum Inlet 8/27/2014 Hood Canal 9 9/4/2014 Drayton Harbor 9/4/2014 Peale Passage 9/5/2014 Annas Bay 9/15/2014 Nisqually Reach 9/15/2014 Burley Lagoon 9/19/2014 5 tlh level Sporadic illness tlh level and sporadic illness High Vibrio Level Closure Growing Area Closure Date Reopening -

Natonal Register of Historic Places •-•Vcu «F I Multiple

NPS Form 10-900-0 (Jan 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service RECEIVED dl Natonal Register of Historic Places •-•vcu «f I Multiple Property Documentation Form ' /W 2 01995 This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic j Lexts. See instructions n Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each ijem.b_^markinc box or bj entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-9J A. Name of Multiple Property Listing NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Related Cultural Resources Along Budd Inlet, Thurston County, WA, Prehistory to 1943 B. Associated Historic Contexts____________________________________________ Maritime History of Budd Inlet C. Geographical Data_______________________________________________ The area is adjacent to or inmediately upland within 1000 feet of Budd Inlet on Puget Sound from Dofflemyer Point on the east, south to Olympia, north of Capitol Lake and west to Cooper Point. These are the properties which were considered to fall within the close water to land relationship addressed in this document. LJSee continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related/p/operties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requ/reFfients set fo/ffi in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature ertifying official Date Washin on State Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

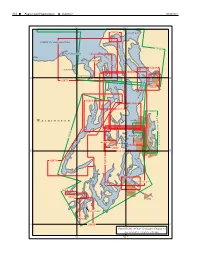

Appendix B: Inventory

THURSTON COUNTY SHORELINE MASTER PROGRAM UPDATE Inventory and Characterization Report Final Draft – June 30, 2013 APPENDIX B: INVENTORY Introduction Thurston County is currently updating its Shoreline Master Program (SMP). As a part of this update, the County initiated its Shoreline Inventory process in November 2007. The Shoreline Inventory was conducted according to the County’s SMP Grant Proposal and the provisions in Washington Administrative Code (WAC) 173-26-201(3)(c). The purpose of the Shoreline Inventory was to identify the baseline of available information on which to base the Analysis and Characterization (document to which this appendix is attached). The Inventory presented here, primarily in matrix form, is the result of an initial collection/collation of information, review on the part of the County and its Scientific Technical Advisory Council (STAG), and subsequent revision. The following Inventory is representative of identified (and dismissed) information sources following those reviews. Subsequent to the inventory review, and over the course of the Analysis and Characterization process, additional geospatial data has been provided by the Thurston County Geodata Center, and the Thurston County Planning Department. Those data are identified in Appendix C, but have not been specifically incorporated into this Inventory. During the Inventory process, a thorough review of existing information was conducted. General sources for information included: Thurston County’s document library (hard copy and digital); Thurston County’s geodata library (map products and GIS data, including County versions of other State geodata resources); Publically available geodata (various on-line mapping programs); and Other publically available documents, reports, and information pertinent to Thurston County (digital and hardcopy). -

Hope Island State Park Hope Island State Park

$ Q ! B % > B ! > ! ! ¼ ! ! D ! $ ! ¼ ! ¼ % ¼ ! ! ¼% $ ! ¼ % % !$ ! !! ! %% $¼ $ ¼ % ! ¼ ¼ % % % % ¼ % % % ¼$ % % > ¼ ¼ $ ! ! ¼ ! ! ¼ !! ¼ % ¼ % Q % ¼ %$ B $ ¼ ! ! ! ! % $ ¼ % ! : ! ¼ ! ! ¼ % $ % ¼ ¼ % % % ¼ D $ : > B % > % % ¼ % ! ! !$ ¼ % $ % B > ! % D ¼ D > > $ % B % : $ B $ % : > % B : B : B ¼ $ % % $ ¼ > : $ ! B Q % ¼ [ D ! % ¼ ! % % % $ ¼ ¼ % % Q ¼ $ % ú ¼ $ ¼ % B> ¼ % : > % % D $ ! B D $ % % Q D $ B % $ ¼ % B : % $ > ¼ Q ! > % % D %% $ ! ¼ B $ % ¼ % ¼ % D % % ¼ % > B $ % f ¼ Q % B $ B % B $ ¼ > % % > > % D $ % % B > % $ D Q > % ¼ ¼ Q % % ¼ D $ : : % ¼ $ > ! > B % ! > % B Q South Sound South Sound/Hope Island State Park Hope Island State Park Cascadia Marine Trail Hope Island State Park This jewel of an island plays host to an old farm and serene hiking trails. If you’re Number of Sites: Overflow Camping: there in the fall, bring an appetite for the apples that abound near the site. Keep 2 group sites (please do not camp in Yes, 8 other sites in a different area on your eyes peeled for the semi-tame deer which feed in the orchard clearing and near the orchard) island, but walkable. caretaker's house. Great view of Mt. Rainier from the steps down to the beach. Water: Sanitation Facilities: Natural History: No Vault toilet approx. 150 ft NE of site. Hope Island was named by Commander Charles Wilkes for one of his crew in 1841. Wilkes Extras: Ownership: was engaged in the mission of charting Puget Sound. The sea-life in the area consists of Mc Micken Island SP A hiking trail around the island Washington State Parks and Recreation beds of huge sea stars, sea cucumbers, shellfish,UV3 shrimp, and a variety of fish. Look for bioluminescence in the water on_ mid-summer nights. Fees: Fire Restrictions: ! H H H H H _H $12/night for up to 8 in site Gas-burning stoves only. -

Budd Inlet Scientific Study: an Overview of Findings

LOTT August 2000 Wastewater Resource Management Plan Budd Inlet Scientific Study: An Overview of Findings The LOTT Partners – Lacey, Olympia, Tumwater, and Thurston County – have invested over $3 million in an 18-month long scientific study of Budd Inlet. The results helped show to what extent Budd Inlet could be relied upon for continued and/or expanded discharge of the community’s treated wastewater flows in the future. If environmentally acceptable, additional winter discharge could offer a comparatively low cost way to gain reserve capacity as LOTT moves toward new wastewater recycling options. The scientific study final report was published in August 1998, and findings are also summarized in LOTT’s Wastewater Resource Management Plan. Summary of Study Findings The Budd Inlet Scientific Study is designed to answer several questions What’s Inside? which are key to LOTT’s Wastewater Resource Management Plan. The following presents a capsule summary of some answers offered by the Budd Inlet’s “Bathtub Theory” is Down the Drain ....... page 2 study: • Initial modeling results confirm that increased winter LOTT discharge Beachcombers Contribute to Budd Inlet Study .......... page 2 won’t harm Budd Inlet. Dissolved oxygen levels and other key water Study Pinpoints Bacteria Sources ............................... page 3 quality factors will remain largely unchanged. • Circulation in Budd Inlet is much stronger than previously under- Dissolved Oxygen Impacted by Plankton Growth ...... page 3 stood. Follow the Nutrients ................................................. page 3 • Circulation is good in both winter and Sediments Don’t Muddy the Waters .......................... page 3 summer months – it takes just 8 to 12 Scientific Information Collected days to replace the for Budd Inlet Study ................................................. -

Movement Patterns of Coastal Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus Clarki Clarki) in South Puget Sound, Washington 2006-2007

Movement Patterns of Coastal Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus clarki clarki) in South Puget Sound, Washington 2006-2007. by Sarah R. Haque A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Environmental Study The Evergreen State College June 2008 2008 by Sarah R. Haque. All rights reserved. This Thesis for the Master of Environmental Study Degree by Sarah R. Haque has been approved for The Evergreen State College by ________________________ Amy Cook PhD Member of the Faculty ________________________ Paul Butler PhD Member of the Faculty ________________________ Joseph M. Jauquet, PhD, MES ________________________ Date Abstract Movement Patterns of Coastal Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus clarki clarki) in South Puget Sound, Washington 2006-2007. Sarah Haque Few studies have focused on the anadromous life-history form of coastal cutthroat. Migratory pathways of coastal cutthroat, especially short-distance estuarine migrations, are even less understood. Previous studies on coastal cutthroat trout primarily focused on freshwater systems and described spawning and rearing characteristics, population structures, and genetics of the freshwater life-history forms. This study collected baseline data on movements and nearshore habitat use of two sample populations (Totten-Little Skookum Inlets and Squaxin/Hope Island) of anadromous coastal cutthroat trout in South Puget Sound using acoustic tracking technology. A total of forty cutthroat were captured in their marine environment, surgically implanted with acoustic transmitters and tracked for eight months via a network of multi-channel acoustic receivers placed throughout the deep South Sound area of South Puget Sound. Analysis suggested a difference in movement patterns and distances traveled between sample populations; however, the overall trend for both sample groups was a movement towards the extreme terminal areas of the study area. -

OFR 2003-25, Geologic Map of the Tumwater 7.5-Minute Quadrangle, Thurston County, Washington

WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES OPEN FILE REPORT 2003-25 Division of Geology and Earth Resources Ron Teissere - State Geologist 122°52¢30² 123°00¢00² R.3W. R.2W. 57¢30² 55¢00² 47°07¢30² 47°07¢30² Qps INTRODUCTION DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS and boulders commonly faceted and (or) striated; ranges in ACKNOWLEDGMENTS adjacent oceans during the last glaciation: Geological Society of Qgt Qgof Qp Qgt Qp thickness from wispy, discontinuous layers less than 1 in. America DNAG Geology of North America, v. K-3, p. 111-125. Qp The Tumwater quadrangle is located at the south end of Puget Sound Quaternary Unconsolidated Deposits We have benefited greatly from discussions with Derek Booth and Qls Qps thick to more than 30 ft thick; thicknesses of 2 to 10 ft are In Qa and includes the cities of Tumwater and Olympia. The quadrangle is Kathy Troost (Univ. of Wash.) and Ray Wells and Brian Sherrod (U.S. Morrison, R. B., 1991, Introduction. Morrison, R. B., editor, Qp most common; may include outwash clay, sand, silt, and Qgt mostly urban and residential land. HOLOCENE NONGLACIAL DEPOSITS Geological Survey). This map is supported by the National Geologic Quaternary nonglacial geology—Conterminous U.S.: Geological Qps gravel, or ablation till that is too thin to substantially mask Qp Mapping Program under Cooperative Agreement No. 01HQAG0105 Society of America DNAG Geology of North America, v. K-2, p. 1- Qpg Fill—Clay, silt, sand, gravel, organic matter, shells, rip-rap, the underlying, rolling till plain; erratic boulders are Qf with the U.S.