II. Urban Geographies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aalseth Aaron Aarup Aasen Aasheim Abair Abanatha Abandschon Abarca Abarr Abate Abba Abbas Abbate Abbe Abbett Abbey Abbott Abbs

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 35 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 306 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 98.500 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

Albuquerque Morning Journal, 01-02-1910 Journal Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 1-2-1910 Albuquerque Morning Journal, 01-02-1910 Journal Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_mj_news Recommended Citation Journal Publishing Company. "Albuquerque Morning Journal, 01-02-1910." (1910). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ abq_mj_news/3879 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIXTEEN PAGE- S- ALBUQUERQUE MO THIRTY-FIRS- T an- -. YEAR, Vol. CXXV., No. 2. ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO, SUNDAY, JANUARY 2, 1910. fit nnn 1unfh- huusk- f H.-- . o- hm. ' r-- M .ssu.. netiv ily. It I ii tu be reasonably ox poet, d ' thill till- - Hlaili) lililí ('iH lliti districts, ,'11 ho dointr KuriO't blip," mill you ran GREAT YEAR AHEAD FOR afford hi keep your ei,. on vmir mvn WHITE BREETVVAB DEDULRED i humo district in tho Sandui and .Man- -' rano mountains lor thiiivas will ho do-- . Inn there l ulo- I am mistaken HUt'l w ill wn- - Now Mexico v. , II started to- - j !0ENLE nn a prod uocr cop-- ward tier place a3 of I DAY 'f WnTt"r!f mm mm 1 ALBUQUERQUE IRE por, loud and zinc. She ii!r"aily has! REÍCEPTIDN TRAGEDY POVERTY PLEA II 1 t i I hor plaoo as a oonl producer, lavel-- j 1 ill fiifw w k mm mmt mm iopmi'iit of otht-- mineral resources j will prohahly ho slow or, huí w,. -

Banquettes and Baguettes

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Banquettes and Baguettes “In the city’s early days, city blocks were called islands, and they were islands with little banks around them. Logically, the French called the footpaths on the banks, banquettes; and sidewalks are still so called in New Orleans,” wrote John Chase in his immensely entertaining history, “Frenchmen, Desire Good Children…and Other Streets of New Orleans!” This was mostly true in 1949, when Chase’s book was first published, but the word is used less and less today. In A Creole Lexicon: Architecture, Landscape, People by Jay Dearborn Edwards and Nicolas Kariouk Pecquet du Bellay de Verton, one learns that, in New Orleans (instead of the French word trottoir for sidewalk), banquette is used. New Orleans’ historic “banquette cottage (or Creole cottage) is a small single-story house constructed flush with the sidewalk.” According to the authors, “In New Orleans the word banquette (Dim of banc, bench) ‘was applied to the benches that the Creoles of New Orleans placed along the sidewalks, and used in the evenings.’” This is a bit different from Chase’s explanation. Although most New Orleans natives today say sidewalks instead of banquettes, a 2010 article in the Time-Picayune posited that an insider’s knowledge of New Orleans’ time-honored jargon was an important “cultural connection to the city”. The article related how newly sworn-in New Orleans police superintendent, Ronal Serpas, “took pains to re-establish his Big Easy cred.” In his address, Serpas “showed that he's still got a handle on local vernacular, recalling how his grandparents often instructed him to ‘go play on the neutral ground or walk along the banquette.’” A French loan word, it comes to us from the Provençal banqueta, the diminutive of banca, meaning bench or counter, of Germanic origin. -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Old San Juan

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 OLD SAN JUAN HISTORIC DISTRICT/DISTRITO HISTÓRICO DEL VIEJO SAN JUAN Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Old San Juan Historic District/Distrito Histórico del Viejo San Juan Other Name/Site Number: Ciudad del Puerto Rico; San Juan de Puerto Rico; Viejo San Juan; Old San Juan; Ciudad Capital; Zona Histórica de San Juan; Casco Histórico de San Juan; Antiguo San Juan; San Juan Historic Zone 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Western corner of San Juan Islet. Roughly bounded by Not for publication: Calle de Norzagaray, Avenidas Muñoz Rivera and Ponce de León, Paseo de Covadonga and Calles J. A. Corretejer, Nilita Vientos Gastón, Recinto Sur, Calle de la Tanca and del Comercio. City/Town: San Juan Vicinity: State: Puerto Rico County: San Juan Code: 127 Zip Code: 00901 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: X District: _X_ Public-State: X_ Site: ___ Public-Federal: _X_ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 699 128 buildings 16 6 sites 39 0 structures 7 19 objects 798 119 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 772 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form ((Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 OLD SAN JUAN HISTORIC DISTRICT/DISTRITO HISTÓRICO DEL VIEJO SAN JUAN Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Plaaces Registration Form 4. -

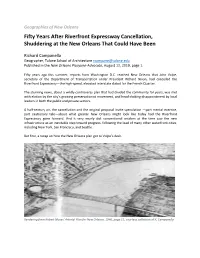

Riverfront Expressway Cancellation, Shuddering at the New Orleans That Could Have Been

Geographies of New Orleans Fifty Years After Riverfront Expressway Cancellation, Shuddering at the New Orleans That Could Have Been Richard Campanella Geographer, Tulane School of Architecture [email protected] Published in the New Orleans Picayune-Advocate, August 12, 2019, page 1. Fifty years ago this summer, reports from Washington D.C. reached New Orleans that John Volpe, secretary of the Department of Transportation under President Richard Nixon, had cancelled the Riverfront Expressway—the high-speed, elevated interstate slated for the French Quarter. The stunning news, about a wildly controversy plan that had divided the community for years, was met with elation by the city’s growing preservationist movement, and head-shaking disappointment by local leaders in both the public and private sectors. A half-century on, the cancellation and the original proposal invite speculation —part mental exercise, part cautionary tale—about what greater New Orleans might look like today had the Riverfront Expressway gone forward. And it very nearly did: conventional wisdom at the time saw the new infrastructure as an inevitable step toward progress, following the lead of many other waterfront cities, including New York, San Francisco, and Seattle. But first, a recap on how the New Orleans plan got to Volpe’s desk. Rendering from Robert Moses' Arterial Plan for New Orleans, 1946, page 11, courtesy collection of R. Campanella The initial concept for the Riverfront Expressway emerged from a post-World War II effort among state and city leaders to modernize New Orleans’ antiquated regional transportation system. Toward that end, the state Department of Highways hired the famous—many would say infamous—New York master planner Robert Moses, who along with Andrews & Clark Consulting Engineers, released in 1946 his Arterial Plan for New Orleans. -

In Search of the Amazon: Brazil, the United States, and the Nature of A

IN SEARCH OF THE AMAZON AMERICAN ENCOUNTERS/GLOBAL INTERACTIONS A series edited by Gilbert M. Joseph and Emily S. Rosenberg This series aims to stimulate critical perspectives and fresh interpretive frameworks for scholarship on the history of the imposing global pres- ence of the United States. Its primary concerns include the deployment and contestation of power, the construction and deconstruction of cul- tural and political borders, the fluid meanings of intercultural encoun- ters, and the complex interplay between the global and the local. American Encounters seeks to strengthen dialogue and collaboration between histo- rians of U.S. international relations and area studies specialists. The series encourages scholarship based on multiarchival historical research. At the same time, it supports a recognition of the represen- tational character of all stories about the past and promotes critical in- quiry into issues of subjectivity and narrative. In the process, American Encounters strives to understand the context in which meanings related to nations, cultures, and political economy are continually produced, chal- lenged, and reshaped. IN SEARCH OF THE AMAzon BRAZIL, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE NATURE OF A REGION SETH GARFIELD Duke University Press Durham and London 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Scala by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in - Publication Data Garfield, Seth. In search of the Amazon : Brazil, the United States, and the nature of a region / Seth Garfield. pages cm—(American encounters/global interactions) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

New Orleans FREE Attractions and Sites

map not to scale to not map map not to scale to not map PM 7 WT 6 WT 5 WT map not to scale to not map New Orleans WT1 FREE Attractions and Sites The New Orleans Power Pass includes admission to some of the most popular paid attractions and tours in New Orleans. The city is also home to a number of great attractions and sites that don’t charge admission. So while you won’t need your Power Pass to get in, you may enjoy spending time exploring the following locations: Bourbon Street Bourbon street is a famous and historic street VISIT THE BEST VISIT THE BEST that runs the length of the French Quarter. When founded in 1718, the city was originally centered New Orleans Attractions New Orleans Attractions around the French Quarter. New Orleans has since expanded, but “The Quarter” remains the cultural for ONE low price! for ONE low price! hub, and Bourbon Street is the street best known by visitors. The street is home to many bars, restaurants, clubs, as well as t-shirt and souvenir Terms & Conditions shops. Bourbon Street is alive both day and night, particularly during the French Quarter’s many New Orleans Power Pass has done its best to ensure the accuracy of the information about the attractions described on our web site and in our festivals - the most popular of these being Mardi guides. However, conditions at these attractions may change at any time. Gras, when Bourbon Street teems with hundreds of We cannot guarantee that each facility will continue to honor its indicated thousands of tourists. -

Common Catalogue of Varieties of Vegetable Species 28Th Complete Edition (2009/C 248 A/01)

16.10.2009 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 248 A/1 II (Information) INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS AND BODIES COMMISSION Common catalogue of varieties of vegetable species 28th complete edition (2009/C 248 A/01) CONTENTS Page Legend . 7 List of vegetable species . 10 1. Allium cepa L. 10 1 Allium cepa L. — Aggregatum group — Shallot . 10 2 Allium cepa L. — Cepa group — Onion or Echalion . 10 2. Allium fistulosum L. — Japanese bunching onion or Welsh onion . 34 3. Allium porrum L. — Leek . 35 4. Allium sativum L. — Garlic . 41 5. Allium schoenoprasum L. — Chives . 44 6. Anthriscus cerefolium L. — Hoffm. Chervil . 44 7. Apium graveolens L. 44 1 Apium graveolens L. — Celery . 44 2 Apium graveolens L. — Celeriac . 47 8. Asparagus officinalis L. — Asparagus . 49 9. Beta vulgaris L. 51 1 Beta vulgaris L. — Beetroot, including Cheltenham beet . 51 2 Beta vulgaris L. — Spinach beet or Chard . 55 10. Brassica oleracea L. 58 1 Brassica oleracea L. — Curly kale . 58 2 Brassica oleracea L. — Cauliflower . 59 3 Brassica oleracea L. — Sprouting broccoli or Calabrese . 77 C 248 A/2 EN Official Journal of the European Union 16.10.2009 Page 4 Brassica oleracea L. — Brussels sprouts . 81 5 Brassica oleracea L. — Savoy cabbage . 84 6 Brassica oleracea L. — White cabbage . 89 7 Brassica oleracea L. — Red cabbage . 107 8 Brassica oleracea L. — Kohlrabi . 110 11. Brassica rapa L. 113 1 Brassica rapa L. — Chinese cabbage . 113 2 Brassica rapa L. — Turnip . 115 12. Capsicum annuum L. — Chili or Pepper . 120 13. Cichorium endivia L. 166 1 Cichorium endivia L. -

A Presentation of the Historic New Orleans Collection 533 Royal Street New Orleans, Louisiana 70130 (504) 523-4662 •

From the Director 2 Schedule 3 Sesssions and Speakers 4 French Quarter Antiques Stroll 14 French Quarter Open House Tour 15 French Quarter Dining Options 17 About The Collection 20 New Orleans Antiques Forum 2009 21 Acknowledgments A presentation of The Historic New Orleans Collection 533 Royal Street New Orleans, Louisiana 70130 (504) 523-4662 • www.hnoc.org NOAF Program final2.indd 1 7/31/08 8:29:09 AM FROM THE DIRECTOR Welcome to the inaugural New Orleans Antiques Forum, and thank you for joining us for the exciting beginning of a new tradition. The Historic New Orleans Collection, home to a vast array of historical decorative arts and situated in the Vieux Carré, is an ideal loca- tion for the exploration and examination of antiques. We look forward to hosting the New Orleans Antiques Forum for years to come, with new topics and speakers at each forum. This event has been in the works for several years, and we would not be here today were it not for the dedication and tireless efforts of many people, especially our generous sponsors. I wish to extend special thanks to L’Hermitage, Evergreen, and Whitney plantations for opening their doors for our pre-forum plantation tour, and to Eugene Cizek and Lloyd Sensat for providing history along the way. The tour sold out very quickly, so register early for next year’s optional trip. I am also grateful to our speakers and the institutions they represent; their support of this event is sincerely appreciated. In addition, I thank the antique shops who will stay open late on a Friday in August for our French Quarter Antiques Stroll, as well as those individuals who will open their homes to attendees on Saturday. -

Hand-Built Ceramics at 810 Royal and Intercultural Trade in French Colonial New Orleans

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Summer 8-5-2019 Hand-built Ceramics at 810 Royal and Intercultural Trade in French Colonial New Orleans Travis M. Trahan [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Trahan, Travis M., "Hand-built Ceramics at 810 Royal and Intercultural Trade in French Colonial New Orleans" (2019). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2681. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2681 This Thesis-Restricted is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis-Restricted in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis-Restricted has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hand-Built Ceramics at 810 Royal and Intercultural Trade in French Colonial New Orleans A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Urban Studies by Travis Trahan B.A. Loyola University of New Orleans, 2015 August, 2019 Table of Contents List of Figures and List of Tables ..................................................................................... -

Louisiana 2 Historic Tax Credit Economic Data 2002-2018

FEDERAL HISTORIC Rep. Cedric Richmond TAX CREDIT PROJECTS Louisiana | District 2 A total of 878 Federal Historic Tax Credit projects received Part 3 certifications from the National Park Service between fiscal year 2002 through 2018, resulting in over $2,956,092,700 in total development. Data source: National Park Service, 2018 ¦¨§55 ¦¨§59 Baton Rouge 3 ¦¨§12 Bayou Goula White Castle ¦¨§10 6 Donaldsonville Garyville New Orleans Vacherie Pauline ¦¨§310 860 Gretna Federal Historic Tax Credit Projects !( 1 !( 6 to 10 0 90 180 360 540 (! 2 to 5 11 and over !( Miles [ Provided by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Historic Tax Credit Coalition For more information, contact Shaw Sprague, NTHP Senior Director of Government Relations | (202) 588-6339 | [email protected] or Patrick Robertson, HTCC Executive Director | (202) 302-2957 | [email protected] Louisiana District 2 Economic Impacts of Federal HTC Investment, FY02 - FY18 Total Qualified Rehabilitation Expenditures Provided by National Park Service Total Number of Projects Rehabilitated: ( 878) Total Development Costs: ($ 2,956,092,700) Total Qualified Rehabilitation Expenditures: ($ 2,570,515,391) Federal HTC Amount: ($ 514,103,078) Preservation Economic Impact Model (PEIM) Investment Data Created by Rutgers University for the National Park Service Total Number of Jobs Created: 45738 Construction: 21243 Permanent: 24495 Total Income Generated: ($ 2,514,735,500) Household: ($ 1,368,475,400) Business: ($ 1,146,260,100) Total Taxes Generated: ($ 530,861,400) Local: ($ 59,523,500) State: ($ 71,460,100) Federal: ($ 399,877,800) Louisiana – 2nd Congressional District Historic Tax Credit Projects, FY 2002-2018 Project Name Address City Year Qualified Use Expenditures Olinde's Furniture Store 1854 North Street Baton Rouge 2014 $6,119,373 Housing Scott Street School 900 N 19th Street Baton Rouge 2012 $2,649,385 Housing no reported project name 724 Europe Street Baton Rouge 2001 $58,349 Not Reported J. -

A Perceptual History of New Orleans Neighborhoods

June 2014 http://www.myneworleans.com/New-Orleans-Magazine/ A Glorious Mess A perceptual history of New Orleans neighborhoods Richard Campanella Tulane School of Architecture We allow for a certain level of ambiguity when we speak of geographical regions. References to “the South,” “the West” and “the Midwest,” for example, come with the understanding that these regions (unlike states) have no precise or official borders. We call sub-regions therein the “Deep South,” “Rockies” and “Great Plains,” assured that listeners share our mental maps, even if they might outline and label them differently. It is an enriching ambiguity, one that’s historically, geographically and culturally accurate on account of its imprecision, rather than despite it. (Accuracy and precision are not synonymous.) Regions are largely perceptual, and therefore imprecise, and while many do embody clear geophysical or cultural distinctions – the Sonoran Desert or the Acadian Triangle, for example – their morphologies are nonetheless subject to the vicissitudes of human discernment. Ask 10 Americans to delineate “the South,” for instance, and you’ll get 10 different maps, some including Missouri, others slicing Texas in half, still others emphatically lopping off the Florida peninsula. None are precise, yet all are accurate. It is a fascinating, glorious mess. So, too, New Orleans neighborhoods – until recently. For two centuries, neighborhood identity emerged from bottom-up awareness rather than top-down proclamation, and mental maps of the city formed soft, loose patterns that transformed over time. Modern city planning has endeavored to “harden” these distinctions in the interest of municipal order – at the expense, I contend, of local cultural expressiveness.