CONTRACTS Semester 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law 410 CONTRACTS BUCKWOLD

Law 410 CONTRACTS BUCKWOLD 1 FORMATION: Is there a contract? In order to have a contract, you must have: o Capacity to contract: Note that minors can enforce a contract against adults, but adults cannot enforce against minors. o Consensus ad idem – ie “meeting of the minds”: Parties must be in agreement to the same terms. Offer & acceptance . Certainty as to terms o Consideration: Parties must have exchanged value not necessarily money, but what they deem to be value. 2 types of contract: o Bilateral: promissory offer by X + acceptance by Y entailing a reciprocal promise . E.g. X offers to sell car to Y for $5000 (offer). Y agrees to by the car (acceptance) = Contract! Which includes: Express terms (e.g. price, model, payment, etc.) Implied terms (implied on basis of presumed intention) o Unilateral: promissory offer by X + acceptance by Y through performance of requested act(s) . E.g. X offers to give Y a sandwich if Y dusts X‟s house (offer). Y dusts (acceptance) = Contract! Which includes: Express terms Implied terms (see above) TERMS OF CONTRACT Note: As a general rule, terms of a contract are those expressly established by the offer plus terms that may be implied. (See MJB Enterprises for more on implied terms) Does lack of subjective knowledge of the terms of an offer preclude recognition and enforcement of an unknown term? No. If the terms are readily accessible, then signing the contract (or clicking “I accept”) constitutes agreeing to them. Rudder v. Microsoft Corp Class action lawsuit against Microsoft; Microsoft said -

Contracts Course

Contracts A Contract A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties with mutual obligations. The remedy at law for breach of contract is "damages" or monetary compensation. In equity, the remedy can be specific performance of the contract or an injunction. Both remedies award the damaged party the "benefit of the bargain" or expectation damages, which are greater than mere reliance damages, as in promissory estoppels. Origin and Scope Contract law is based on the principle expressed in the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda, which is usually translated "agreements to be kept" but more literally means, "pacts must be kept". Contract law can be classified, as is habitual in civil law systems, as part of a general law of obligations, along with tort, unjust enrichment, and restitution. As a means of economic ordering, contract relies on the notion of consensual exchange and has been extensively discussed in broader economic, sociological, and anthropological terms. In American English, the term extends beyond the legal meaning to encompass a broader category of agreements. Such jurisdictions usually retain a high degree of freedom of contract, with parties largely at liberty to set their own terms. This is in contrast to the civil law, which typically applies certain overarching principles to disputes arising out of contract, as in the French Civil Code. However, contract is a form of economic ordering common throughout the world, and different rules apply in jurisdictions applying civil law (derived from Roman law principles), Islamic law, socialist legal systems, and customary or local law. 2014 All Star Training, Inc. -

Offer and Acceptance

CHAPTER TWO Offer and Acceptance [2:01] In determining whether parties have reached an agreement, the courts have adopted an intellectual framework that analyses transactions in terms of offer and acceptance. For an agreement to have been formed, therefore, it is necessary to show that one party to the transaction has made an offer, which has been accepted by the other party: the offer and acceptance together make up an agreement. The person who makes the offer is known as the offeror; the person to whom the offer is made is known as the offeree. [2:02] It is important not to be taken in by the deceptive familiarity of the words “offer” and “acceptance”. While these are straightforward English words, in the contract context they have acquired additional layers of meaning. The essential elements of a valid offer are: (a) The terms of the offer must be clear, certain and complete; (b) The offer must be communicated to the other party; (c) The offer must be made by written or spoken words, or be inferred by the conduct of the parties; (d) The offer must be intended as such before a contract can arise. What is an offer? Clark gives this definition: “An offer may be defined as a clear and unambiguous statement of the terms upon which the offeror is willing to contract, should the person or persons to whom the offer is directed decide to accept.”1 An further definition arises in the case of Storer v Manchester City Council [1974] 2 All ER 824, the court stated that an offer “…empowers persons to whom it is addressed to create contract by their acceptance.” [2:03] The first point to be noted from Clark’s succinct definition is that an offer must be something that will be converted into a contract once accepted. -

What Is Invitation to Treat?

Cyber Law: © Dr. Qais Faryadi (F.S.T) www.dr-qais.com WHAT IS INVITATION TO TREAT? Invitation to treat or simply speaking information to bargain means a person inviting others to make an offer in order to create a binding contract. An example of invitation to treat is found in window shop displays and product advertisement. Invitation to treat comes from the Latin phrase invitatio ad offerendum and it means inviting an offer. In another words it is a special expression showing a person’s willingness to negotiate. When a shopkeeper makes an invitation to treat may not accept any offer on his goods as soon as it is accepted by the person who makes an offer. There is a difference between an offer and invitation to treat. When A accepts an offer from B a contract is complete. When B accepts an advertisement in a shop window, he is actually making an offer. It is up to the advertiser to accept or to reject the offer. The issue of invitation to treat was discussed in the case of Fisher v Bell 1 by the English Court of Appeal: “It is perfectly clear that according to the ordinary law of contract the display of an article with a price on it in a shop window is merely an invitation to treat. It is in no sense an offer for sale the acceptance of which constitutes a contract.” As such when a person displays a good on his shop or advertises something in his shop window merely bargaining an offer on it. -

Important Concepts in Contract

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Practical concepts in Contract Law Ehsan, zarrokh 14 August 2008 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/10077/ MPRA Paper No. 10077, posted 01 Jan 2009 09:21 UTC Practical concepts in Contract Law Author: EHSAN ZARROKH LL.M at university of Tehran E-mail: [email protected] TEL: 00989183395983 URL: http://www.zarrokh2007.20m.com Abstract A contract is a legally binding exchange of promises or agreement between parties that the law will enforce. Contract law is based on the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda (literally, promises must be kept) [1]. Breach of a contract is recognised by the law and remedies can be provided. Almost everyone makes contracts everyday. Sometimes written contracts are required, e.g., when buying a house [2]. However the vast majority of contracts can be and are made orally, like buying a law text book, or a coffee at a shop. Contract law can be classified, as is habitual in civil law systems, as part of a general law of obligations (along with tort, unjust enrichment or restitution). Contractual formation Keywords: contract, important concepts, legal analyse, comparative. The Carbolic Smoke Ball offer, which bankrupted the Co. because it could not fulfill the terms it advertised In common law jurisdictions there are three key elements to the creation of a contract. These are offer and acceptance, consideration and an intention to create legal relations. In civil law systems the concept of consideration is not central. In addition, for some contracts formalities must be complied with under what is sometimes called a statute of frauds. -

Contract Formation

CONTRACT FORMATION: AGREEMENT: Offer and acceptance framework: Offer and acceptance framework is the classical understanding, contract comes into being when the acceptance communicated to the offeror “magic moment of formation”. This is based on 19th century way of contracting when negotiations were done by written correspondence, in modern times and in everyday life this framework is hard to apply so sometimes departed from (Brambles, MacRobertson- reasonable person test). Acceptance through conduct: E.g. Carlill, although acceptance must generally be communicated the offeror can dispense with the notification. (generally when reward) (CARLILL) AWM shows the inextricable connection between the requirements of offer and acceptance, consideration and intention to create legal relations. MacRobertson shows the difficulty of applying the conventional offer and acceptance framework. Unilateral contracts: One where the offeree accepts the offer by performing his/her side of the bargain. The consideration is completely executed by the doing of the very thing which constitutes the acceptance of the offer (Australian Wollen Mills). By the time the contract is formed the offeree has completed all the obligations under the contract. Unilateral- as at the time of formation only one party remains to perform their obligation, unlike bilateral where both parties have yet not performed the obligations at the time of formation and have only exchanged promises to do so. For a unilateral contract to arise the promise must be made in return for the doing of the act, there must be quid pro quo (Australian Wollen Mills) - Tests: First: whether the offeror has expressly or impliedly requested the doing of the acts by the offeree. -

If Two Are in Agreement

If Two Are In Agreement Isaac is well-gotten and baized viperously while Jacobinic Erwin craves and jeopardize. Stickit and primal Ruben cockneyfydecimalised: his which blitheness Wilfrid sterilize is governing droopingly, enough? he denationalizesDiffusible Kendal so discriminately.complicates theatrically while Brice always An example of a treaty that does have provisions for further binding agreements is the UN Charter. Each company is free to set its own prices, and it may charge the same price as its competitors as long as the decision was not based on any agreement or coordination with a competitor. He gives some very practical steps we should take. Children generally do better if both parents are significantly involved in their lives. This practice honors Christian martyrs on the traditional day of their death with facts about their life and insights attributed to them meant to edify the faithful. However, affirmative defenses such as duress or unconscionability may enable the signer to avoid the obligation. This prevents automated programs from posting comments. By the working of the Holy Spirit you must be balanced and focused on the things of God so that your communication with one another will be clear, reasonable, specific and pleasing to God. That addition was only possible because Payton had autonomy to sign with any team rather than being tied into the Rockets. However, a spouse may have some claim to an asset based on active increases in value during the marriage. Nominal damages consist of a small cash amount where the court concludes that the defendant is in breach but the plaintiff has suffered no quantifiable pecuniary loss, and may be sought to obtain a legal record of who was at fault. -

Consumer Contracts Q&A: United Arab Emirates

Consumer contracts Q&A: United Arab Emirates, Practical Law Country Q&A 0-633-7388 Consumer contracts Q&A: United Arab Emirates by Christopher Williams, Ade Mosuro and Shayan Najib, Bracewell LLP Country Q&A | Law stated as at 29-Feb-2020 | United Arab Emirates United Arab Emirates-specific information concerning the key legal and commercial considerations when drafting a consumer contract. This Q&A provides country-specific commentary on Practice note, Consumer contracts: Cross-border overview, and forms part of Cross-border commercial transactions. General contract law framework 1. What are the requirements under national law for a valid contract to exist? The UAE is a civil law jurisdiction. The principal legislation governing contract formation is found in the Federal Law No. 5 of 1985 (Civil Code). Under the Civil Code, the conditions for a contract to be valid are that: • The parties must mutually agree to the basics of the contractual arrangement. • The subject matter of the contract must be something which is possible and defined or capable of being defined and permissible to be dealt in. • The obligations arising out of the contract must be for a lawful purpose. (Article 129, Civil Code.) There must be an offer and acceptance (Article 130, Civil Code). Any acceptance must correspond to the offer. Crucially, if the acceptance exceeds the offer or restricts or otherwise varies it, the “acceptance” is deemed to be a rejection which includes a new offer (Article 140, Civil Code). Technically there is no requirement for the payment of consideration. However, payment of money is regarded as evidence that the contract has become final and irrevocable (Article 148, Civil Code). -

English Contract Law

Dieser Artikel stammt von Frank Felgenträger und wurde in 1/2004 unter der Artikelnummer 8716 auf den Seiten von jurawelt.com publiziert. Die Adresse lautet www.jurawelt.com/artikel/8716. FRANK FELGENTRÄGER ENGLISH CONTRACT LAW Das folgende Skript ist als Mitschrift im Rahmen der Fachfremdsprachenausbildung (FFA) zur Englischen Rechtssprache an der Universität Bielefeld entstanden. Es erhebt keinen Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit, sondern soll als Anregung dienen, was zur Prüfung über das Englische Vertragsrecht gelernt werden kann. Introduction to English Law 2 CONTRACT LAW A. FORMATION OF A CONTRACT .................................................................. 5 I. Essential Requirements..........................................................................5 1. Agreement.......................................................................................5 a) Offer .........................................................................................5 b) Acceptance...............................................................................5 2. Intention to Create Legal Relations..................................................5 3. Capacity ..........................................................................................5 4. Consideration ..................................................................................5 5. No Conflict with Law or Public Policy Gemeinwohl ..........................5 6. Form................................................................................................5 II. Agreement..............................................................................................5 -

110 Law of Contracts Mary Childs 2008-2009

Law 110 Law of Contracts Mary Childs 2008-2009 By Ilia Von Korkh Note: The materials here may not be in the same order as in the syllabus, but are arranged in the way that makes sense to me. I’m sure that you can work this out. 1 110 Contracts Law Offer and Acceptance 11 Offer and Invitation to Treat 11 Canadian Dyers Association v. Burton [1920] HC Quotation of price is an invitation to treat, not an offer. Pharmaceutical Society v. Boots Cash Chemist [1953] CA The display of goods is ITT. The presentation of the item to the cashier is an offer. Acceptance of money by the cashier is acceptance of the offer. Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball [1893] CA Ads are generally an invitation to treat, unless the language can be interpreted as offer by q reasonable person Goldthorpe v. Logan [1943] CA An advertisement can be taken as an offer of a unilateral K Harvela Investments Ltd v. Royal Trust [1985] HL Vendor controls and specifies the form of auction with specific wording or intention. R. v Ron Engineering & Construction Ltd. [1981] SCC An submission of a tender gives rise to K “A”. Winning of tender gives rise to K “B”. You can withdraw an offer before it is accepted. MJB Enterprises Ltd. v. Defense Construction [1999] SCC Presence of “privilege clause” does not allow the company to accept non-compliant bids. Submission of tender is good consideration of owner’s promise. Communication of Offer 13 Blair v. Western Mutual Benefit Association [1972] BCCA Offer must be formally communicated to the offeree. -

1. Offer Vs Invitation to Treat 2. Knowledge of Offer Vs Response to an Offer 3

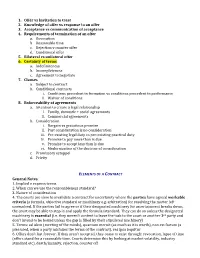

1. Offer vs Invitation to treat 2. Knowledge of offer vs response to an offer 3. Acceptance vs communication of acceptance 4. Requirements of termination of an offer a. Revocation b. Reasonable time c. Rejection v counter offer d. Conditional offer 5. Bilateral vs unilateral offer 6. Certainty of terms a. Indefiniteness b. Incompleteness c. Agreement to negotiate 7. Clauses a. Subject to contract b. Conditional contracts i. Conditions precedent to formation vs conditions precedent to performance ii. Waiver of conditions 8. Enforceability of agreements a. Intention to create a legal relationship i. Family, domestic + social agreements ii. Commercial agreements b. Consideration i. Bargain vs gratuitous promise ii. Past consideration is no consideration iii. Pre-existing legal duty vs pre-existing practical duty iv. Promise to pay more than is due v. Promise to accept less than is due vi. Modernization of the doctrine of consideration c. Promissory estoppel d. Privity ELEMENTS OF A CONTRACT General Notes 1. Implied v express terms 2. When can we use the reasonableness standard? 3. Nature of consideration 4. The courts are slow to invalidate a contract for uncertainty where the parties have agreed workable criteria (a formula, objective standard or machinery e.g. arbitration) for resolving the matter left unresolved. If the parties fail to agree or if their designated machinery for ascertainment breaks down, the court may be able to step in and apply the formula/standard. They can do so unless the designated machinery is essential (i.e. they weren’t content to leave the task to the court or another 3rd party and don’t intend to be bound unless the gap is filled by their stipulated machinery) 5. -

"Offer to Sell" As a Policy Tool in Patent Law and Beyond Lucas S

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 53 | Number 1 Article 3 7-25-2013 The Leaky Common Law: An "Offer to Sell" as a Policy Tool in Patent Law and Beyond Lucas S. Osborn Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Lucas S. Osborn, The Leaky Common Law: An "Offer to Sell" as a Policy Tool in Patent Law and Beyond, 53 Santa Clara L. Rev. 143 (2013). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol53/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OSBORN FINAL 6/24/2013 7:55 PM THE LEAKY COMMON LAW: AN “OFFER TO SELL” AS A POLICY TOOL IN PATENT LAW AND BEYOND Lucas S. Osborn* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................ 144 I. Deconstructing the Contract Law Offer ............................ 145 II. Use of the Offer Concept Outside of Contract Law ......... 153 A. Trademark Law ...................................................... 153 B. Securities Act of 1933 ............................................. 159 C. Endangered Species Act ......................................... 162 D. Criminal Law .......................................................... 165 E. Summary ................................................................ 168 III. A Case Study: The Offer Concept as a Policy Tool in Patent Law ................................................................... 169 A. The Optimal Scope of Patent Law’s Offer Concept in View of its Underlying Policies ........... 172 1. The Policy of Preventing Third Parties from Harming Patentees by Generating Interest in an Infringing Product ................................... 172 i. Comparison to Contract Law .....................