Wealth and Its Social Worth Consumers in the Land of Gandhi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2019-2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 ANNUAL Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 © Gandhi and People Gathering by Shri Upendra Maharathi Mahatma Gandhi by Shri K.V. Vaidyanath (Courtesy: http://ngmaindia.gov.in/virtual-tour-of-bapu.asp) (Courtesy: http://ngmaindia.gov.in/virtual-tour-of-bapu.asp) ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti ANNUAL REPORT - 2019-2020 Contents 1. Foreword ...................................................................................................................... 03 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 05 3. Structure of the Samiti.................................................................................................. 13 4. Time Line of Programmes............................................................................................. 14 5. Tributes to Mahatma Gandhi......................................................................................... 31 6. Significant Initiatives as part of Gandhi:150.................................................................. 36 7. International Programmes............................................................................................ 50 8. Cultural Exchange Programmes with Embassies as part of Gandhi:150......................... 60 9. Special Programmes..................................................................................................... 67 10. Programmes for Children............................................................................................. -

The Lion Awakes Adventures in Africas Economic Miracle 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE LION AWAKES ADVENTURES IN AFRICAS ECONOMIC MIRACLE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ashish J Thakkar | 9781137280145 | | | | | The Lion Awakes Adventures in Africas Economic Miracle 1st edition PDF Book Welcome back. Through the turmoil of leaving Uganda, a day-old daughter in her arms, to making decisions that would protect us in Rwanda, she was — and is — our rock. It's the year anniversary for Mara in August. Rating details. A rather interesting, challenging book; something that at first one feared would be a bit of a tiresome, egocentric personal reflection but within a few paragraphs the author had expertly sold the idea to the reader. In several areas, Africa still accounts for less than its expected share of global activity. His family's efforts to rebuild their lives inspired him to drop out of school at 15 and start an IT business, buying and selling computer parts. Equally damaging is the silent exodus of its young professionals to the West in search of the 'better life'. This interview has been edited for clarity and length. My parents, my sister, and I were refugees for 35 of the days of the genocide. Escape the Present with These 24 Historical Romances. All rights reserved. I hated being that little boy. Coronavirus News U. Opinion Show more Opinion. Africa needs to create right skills, provide funding for its young entrepreneurs, says Ashish Thakkar. It's not going to be government-created employment. James Lynam rated it it was amazing Jun 01, A good read overall, it's clear that Thakkar is well versed in technology and industry. -

District Planning Office BHAVNAGAR INDEX Sr

District Human Development Plan (Moving from DHDR to DHDP) District-Bhavnagar District Planning Office BHAVNAGAR INDEX Sr. Particular Page No. No. 1. District Profile 3-15 2. Sector Profile 16-26 Education Sector Health Care, Sanitation and Environment Livelihood Patterns and Opportunities 3. District Specific Issues 27-28 4. Sector Wise Planning 29-38 4 (a): Gap Analysis 4 (b): Action Plan 5. Financial Planning 39-42 Education Sector Health Sector Livelihood and Agriculture Sector 6. Recommendation of DHDR 43-45 7. Success Story 46-51 1 | Page -: Published By :- Shri Banchhanidhi Pani (IAS) Collector and District Magistrate, Bhavnagar -: Edited By :- Shri B. K. Joshi District Planning Officer, Bhavnagar -: Cooperation By :- Shri A. R. Trivedi Senior Project Associate cum Consultant, Bhavnagar Shri K. J. Dave Senior Project Associate, Bhavnagar 2 | Page Chapter-1 3 | Page District Profile Around 1260 AD, they moved down to the Gujarat coast and established three capitals; Sejakpur, Umrala and Sihor. In 1722–1723, forces led by Khanthaji Kadani and Pilaji Gaekwad attempted to raid Sihor but were repelled by Maharaja Bhavsinhji Gohil. After the war Bhavsinhji realised the reason for repeated attack was the location of Sihor (old Bhavnagar). In 1823, he established a new capital near Vadva village, 20 km away from Sihor, and named it Bhavnagar. It was a carefully chosen strategic location because of its potential for maritime trade. Naturally, Bhavnagar City became the capital of Bhavnagar State Bhavnagar Boroz. The old town of Bhavnagar was a fortified town with gates leading to other important regional towns. It remained a major port for almost two centuries, trading commodities with Mozambique, Zanzibar, Singapore, and the Persian Gulf. -

Archana Srivastava

BETWEEN EXPECTATION AND EXPERIENCE: Lives of Gujarati and Sikh women ageing in London Archana Srivastava Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London February 1995 Department of Anthropology and Sociology School Of Oriental And African Studies 1 ProQuest Number: 10673199 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673199 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This ethnographic study traces the ageing process as conditioned by the migration experience, and the social, economic and cultural backgrounds of Gujarati and Sikh women in London. This research was conducted amongst women of the two communities who frequented various Asian organizations and places of worship in Wood Green, Wembley and Southall in London. The data were collected through unstructured interviews. The essential experiences which condition the lives of informants include their migratory history, their residential patterns, the perceived threat from western morality, concern for their cultural identity, and actual and perceived racism. These experiences have demanded various adjustments from Indian women, such as the need to go out of their houses to work. -

Morari Bapu – Translations and Excerpts from Satsangs and Kathas

Morari Bapu – Translations and Excerpts from Satsangs and Kathas Biography Morari Bapu was born to Prabhudas Bapu and Savitri Ma Hariyani on the auspicious day of Maha-Shivratri in Talgajarda, a small village near Mahuva in the District of Bhavnagar and State of Gujarat, India. Born into the Vaishnav Bava Sadhu Nimbarka lineage (parampara) where every male is called “Bapu” from childhood, Morari Bapu is commonly referred to as “Bapu” (meaning Father). Bapu has five brothers and two sisters, and is married with one son, three daughters and several grandchildren. Bapu spent most of his childhood under the guidance of his paternal grandmother, Amrit Ma, often spending hours listening to folk tales from her of traditional India. At the age of five, Bapu began learning the Ram Charit Manas from his paternal grandfather, who is his only Guru, Tribhovandas Bapu. Both of Bapu's paternal grandparents were the influential guiding forces behind his upbringing. Tribhovandas Bapu, affectionately called Dadaji, was a principled and learned scholar of the Ram Charit Manas. He would teach Bapu five couplets (chaupais) with its meaning each day. As the nearest school was approximately seven kilometres from Talgajarda, Bapu would utilise his time while walking to and from school to memorise the couplets with their meanings he had learnt earlier in the day, often singing to the trees and the plant life on his path. Upon his return home, Bapu would recite back to Dadaji what he had memorized. At a young age, Bapu was also encouraged through letters from his paternal grandfather’s brother, Mahamandleshwar Vishnudevanand Giriji Maharaj, an ascetic of the Kailas Ashram in Rishikesh, to be proficient in the Bhagvat Gita and the Vedas. -

Challenges of Tribal Cultural Traditions and Customs: a Study of Gujarat

KCG-Portal of Journals Continuous Issue-47|February – March 2021 Challenges of Tribal cultural Traditions and Customs: A study of Gujarat Abstract Today, the tribals of Gujarat are facing a different problem because they are getting caught up in the so- called development process. The tribals are stuck in a paradoxical situation. On the one hand, they are forced to migrate and migrate in the name of development. On the other hand, the culture of tribals is being destroyed by various means. Such as the tribalization of Sanskritization due to the effect of modernization and urbanization. Due to such problems, tribals are facing the problem of survival. The tribals are being forced to forget their indigenous identity. Tribals are being brought into the mainstream through religion. They are being misled and separated from their culture in the name of religion. The influence of Hindu and Christianity is increasing among the tribals. Religious thinking is being imposed on the tribals through various newspapers and other organized methods. Media is playing an important role in this process. Adivasis are forgetting their traditional and indigenous culture and imitating other's culture. Imitation of Hindu and Christian culture is taking place on a large scale. Both religions are trying to propagate religious thinking and there are also attempts to create communal disputes between religions. Both religions are unilaterally propagated in tribal areas. In the name of religion, the converted Hindu and Christian tribals are forced to fight among themselves. Due to the influence of these religions, tribals are leaving their culture behind and practicing Hindu and Christianity on a large scale. -

S P E C I a L E D I T I

CELEBRATING 50 YEARS OF SANGH IN THE UK SPECIAL EDITION sev yam ak a Sa w n S g u h d U n i K H • • m S ymve gº Ne ¥t a Sv | n n a s th k Est. 1966 a a¯ g r • n Sewa¯ • Sa FIFTY YEARS OF CONTRIBUTION 1 2 taking you through 50 years... 3 Contents Invocations Bob Blackman (MP) Praises HSS Activities Golden Jubilee Geet – Jay Ghosh Sanskriti Ka History and Relevance of Sangh Geet Editorial Important Sangh Departments Goodwill Messages Images from 1996 to 2006 Images from 1966 to 1976 Glimpse of Activities of HSS UK Sanskaar Sewa Sanghathan Evolution of Shakha in UK Before the Formation of HSS Empowering a Child – Balagokulam Early Days of Sangh Work in the UK Hindu Sevika Samiti UK How Ilford Shakha Started The Role of Hindu Women and Samiti Welcome to the 60’s Sewa Activities of HSS (UK) Founding Trustees of HSS (UK) Community Champions Present KKM of HSS (UK) Expansion of HSS UK – Vistaarak Yojana A Few Veterans of the UK Sangh Work Sangh Karyalayas Images from 1976 to 1986 Publications of HSS (UK) Milestone Events Sangh Inspired Organisations Prominent Persons at HSS Events Images from 2006 – 2016 HSS Shakhas on UK Map Experience of Sangh Pariwar Landmarks in the 50 Year Journey Sangh Prarthana of HSS (UK) Sangh Influence on my Life My 26 Years Sojourn in UK Vishwa Dharma Kee Jai! Sangh Shiksha Varg (SSV) Leading through Innovation in UK Sangh Work 4 5 Invocations Invocations asato mā sadgamaya tamaso mā jyotirgamaya mrityormā’mrataṃ gamaya असतो मा सद् गमय तमसो मा !योितग’मय मृयोमा’|मृतं गमय O Almighty, lead me from the untruth to the truth. -

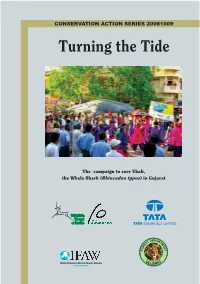

Turning the Tide

CONSERVATION ACTION SERIES 20081009 Turning the Tide The campaign to save Vhali, the Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus) in Gujarat CHEMICALS LIMITED TURNING THE TIDE The campaign to save Vhali, the whale shark (Rhincodon typus) in Gujarat Rupa Gandhi Chaudhary, Dhiresh Joshi, Aniruddha Mookerjee, Vivek Talwar and Vivek Menon for the benefit of the rural population in an around the company’s plants and township. Over the years it has initiated a number of development, welfare and relief activities. TATA Chemicals won the Green Governnance Award 2005 for the Whale Shark Conservation Project. The award was given by Dr Manmohan Singh, Hon’ble Prime Minister of India on November 10, 2005 in New Delhi. Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), is a non-profit conservation organisation, committed to help conserve nature, especially endangered species and threatened habitats, in partnership with communities and governments. Its principal concerns are crisis management and the provision of quick, efficient aid to those areas that require it the most. In the longer term it hopes to achieve, through proactive reforms, an atmosphere conducive to conserving India's wildlife and its habitat. The Gujarat Forest Departmnet is entrusted with the prime responsibility of protection, conservation and development of forests and wldlife of the state. They have extended support to the Whale Shark campaign even beyond the shores of the state. Suggested Citation: Rupa Gandhi Choudhary, Dhiresh The International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) Joshi, Aniruddha Mookerjee, Vivek Talwar and Vivek works to improve the welfare of wild and domestic Menon (2008). Turning the Tide - The campaign to animals through out the world by reducing save Vhali, the whale shark in Gujarat. -

Vaishali Shah Is an Author with Having Written a Unique Book Series on Indian Culture Called Hindu Culture and Lifestyle Studies

Vaishali Shah is an author with having written a unique book series on Indian culture called Hindu Culture and Lifestyle Studies. The book series aims to create awareness about the Indian culture worldwide. She is an avid reader, philanthropist, blogger and traveler. She has master degree in International Business and also done diploma in Internet Technology. Her interest in ancient Indian sciences made her to get into research of scriptures and its related subjects. Founder of Shrivedant Foundation: Shrivedant Foundation was established as a family Trust in the year 2001. The primary aim in setting up this Foundation is to unravel the treasures of our ancient Vedic heritage and make it available to all those who are interested in acquainting themselves with the priceless wisdom that has been handed down the ages. Our effort to secure this legacy has been extremely successful. We have been able to digitize Scriptures and make it available to all seekers at the click of the button in the relative comfort of their homes. We have created more than forty thousand researched content in the field of holistic lifestyle, wellness, health, culture, heritage, lifestyle, yoga and other related subjects. The guiding principle of Shrivedant Foundation is Inspire, Believe, Betterment. The foundation also engages the urban, educated, modern populace across the world with spiritual masters for many intellectual and soul stirring discourses that open up new vistas and unfurls an entirely new purpose to life. Some of the regular activities of the Foundation -

INDEX for Hypocrisy of Swadhyay

INDEX FOR Hypocrisy of Swadhyay INDAX PAGE 1. Hypocrisy of Swadhyay 2 2. Human Dignity & Swadhyay 3 3. Reply to an Email sent by Didi Mrs. 5 Talwalkar 4. Issues 8 5. Gita Ch. 9 V. 22 10 6. Concepts 11 7. Story of Nabhag 13 8. X-Ray of Religious Terrorism 14 9. Intoxication of a Cult 17 10. Mr. Athavale is the root of all the 18 troubles ailing Swadhyay 11. Where are the other Lectures? 22 12. Jai Fraudeshwar 24 13. Books of Swadhyay 25 14. Analysis of Swadhyay Followers 26 15. After Effects 30 16. Thoughts on Swadhyay 30 17. Dada’s Bhav Pheri 32 18. Swadhyay: A Money Making Scam 33 19. Honest Questions 38 20. Bhav Samarpan: True Story 39 21. “Good actions done with bad motives 41 are bad. Bad actions done with good motives are good.” 22. Divine Traits of Swadhyay 42 23. Dada & Morarji Desai 45 24. Unfit 47 25. Practice of Swadhyay 49 26. What is Happning? 50 27. Exaggerated Claim 52 28. Flaw in Explanation 53 29. Crime or Sin? 55 30. Holy Geeta 57 31. Hypocrisy, Thy Name 59 32. Gita Learning 60 33. Krishnam Vande Jagat Gurum 62 34. Vedic Sanskriti & Swadhyay 65 35. Ravan & Pandurang 66 36. Dada vs. Anna 67 37. False Propaganda 70 38. Lessons from Mahabharat 72 39. Implications of Asmita 74 40. Daily Gita Learning 76 Page 1 of 108 41. Hinduism or Christianity 78 42. Which Philosophy 79 43. Gorakh Dhandha 81 44. Recollection of an Old Timer 91 45. Lessons from Ramayan 92 46. -

The Need for Better Political and Emotional Spaces

Quarterly Magazine Volume 2, Issue 3 - June 2020 / Dhul Qa'dah 1441 ISSN 2632-3168 £5 where sold The Nation and the New World: The Need for Better Political and Emotional Spaces AMRIT WILSON ROSHAN SALIH SADEK HAMID JOÃO SILVA JORDÃO From Nagpur to Muslims need to Is a Better World The Underlying Myths Nairobi to Neasden – create their own Possible? Muslims, that Fuel Divisions in tracing global Social Media Leadership and the Islam …and how we Hindutva Platforms Coronavirus Crisis can Demolish them In the Name of Allah, the Most Beneficent, the Most Merciful ndia’s pr oblem with fascism is well docu - also proved to be a useful tool in propagating mented. While many point to the 1992 de - anti-Muslim views. Among the more prepos - molition of the historic Babri Masjid as a terous anti-Muslim campaigns being waged by seminal point in the rise of Hindutva India’s ruling BJP is the Corona-jihad, the idea Contents: Isupremacist politics, the seeds of today’s domi - that Muslims are deliberately infecting Hindus nation of the national political landscape were with the Covid-19 virus in pursuit of a religious planted several decades before India’s first war. As the pandemic rages across India, the prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru hoisted the ubiquity of social media has simply provided 3 Amrit Wilson: national flag above the Lahori Gate of the Red another opportunity to demonise Muslims in From Nagpur to Fort in Delhi in 1947. Far less has been written India, leading amongst other things to the about the spread of these ideas - inspired by scapegoating of the country’s Tabligh-Jamaat Nairobi to Neasden – Mussolini and Hitler - in the Indian diaspora. -

Manual for Inter-Religious Dialogue Manual for Interreligious Dialogue - Chemchemi Ya Ukweli

MANUAL MANUAL The Writers Allan Kalafa Kefa (BA Div-Bread of Life Bible College) is a Pastor, Mentor and life Coach. He is also a trainer and MANUAL in charge of program development at Visionaries Inc- a consultant on Organizational development and leadership development. INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE INTER-RELIGIOUS INTER-RELIGIOUS Ombuge .M. Moses (BA Sociology) is a trainer in participatory approaches and theatre in peace building and an expert in DIALOGUE Drama for conflict transformation. He works with youth and children using drama and film for behaviour change. In Cooperation with: MANUAL FOR INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE MANUAL FOR INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE - CHEMCHEMI YA UKWELI A Publicati on of: Chemchemi Ya Ukweli The Active Non-Violence Movement in Kenya Civil Peace Service Kenya Waumini House P.O. Box 14370-00800 Nairobi-Westlands, Kenya Tel: +254 2 4446570, 4442254 Email: [email protected] Website: www.chemichemi.org Illustrations by Mwangi Gikonyo Printed by: Franciscan Kolbe Press P.O. Box 468 00127 Limuru 2012 Email: [email protected] ii MANUAL FOR INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE MANUAL FOR INTERRELIGIOUS DIALOGUE - CHEMCHEMI YA UKWELI TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms .................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgement ..................................................................................... vii Forward .................................................................................................... ix Introduction ................................................................................................1