SCOTTISH ECCLESIASTICAL SECESSIONS by PRINCIPAL A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minister of the Gospel at Haddington the Life and Work of the Reverend John Brown (1722-1787)

Minister of the Gospel at Haddington The Life and Work of the Reverend John Brown (1722-1787) David Dutton 2018 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wales: Trinity St. David for the degree of Master of Theology in Church History School of Theology, Religious Studies and Islamic Studies Faculty of Humanities and Performing Arts 1 Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. David W Dutton 15 January 2018 2. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in Church History. David W Dutton 15 January 2018 3. This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. David W Dutton 15 January 2018 4. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying, inter- library loan, and for deposit in the University’s digital repository David W Dutton 15 January 2018 Supervisor’s Declaration. I am satisfied that this work is the result of the student’s own efforts. Signed: …………………………………………………………………………... Date: ………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract This dissertation takes a fresh look at the life and work of the Reverend John Brown (1722-1787), minister of the First Secession Church in Haddington and Professor of Divinity in the Associate (Burgher) Synod, who is best known as the author of The Self-Interpreting Bible (1778). -

Elspeth Buchan and the Buchanite Movement

Elspeth Buchan and the Buchanite Movement Author: Jill Strong Author: Rowan Strong Published: 27th April 2021 Jill Strong and Rowan Strong. "Elspeth Buchan and the Buchanite Movement." In James Crossley and Alastair Lockhart (eds.) Critical Dictionary of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements. 27 April 2021. Retrieved from www.cdamm.org/articles/buchanites Origins of the Buchanite Sect Elspeth Buchan (1738–91), the wife of a potter at the Broomielaw Delftworks in Glasgow, Scotland, and mother of three children, heard Hugh White, minister of the Irvine Relief Church since 1782, preach at a Sacrament in Glasgow in December 1782. As the historian of such great occasions puts it, ‘Sacramental [ie Holy Communion] occasions in Scotland were great festivals, an engaging combination of holy day and holiday’, held over a number of days, drawing people from the surrounding area to hear a number of preachers. Robert Burns composed one of his most famous poems about them, entitled ‘The Holy Fair’ (Schmidt 1989, 3).Consequently, she entered into correspondence with him in January 1793, identifying White as the person purposed by God to share in a divine commission to prepare a righteous people for the second coming of Christ. Buchan had believed she was the recipient of special insights from God from as early as 1774, but she had received little encouragement from the ministers she had approached to share her ‘mind’ (Divine Dictionary, 79). The spiritual mantle proffered by Buchan was willingly taken up by White. When challenged over erroneous doctrine by the managers and elders of the Relief Church there within three weeks of Buchan’s arrival in Irvine in March 1783, White refused to desist from preaching both publicly and privately Buchan’s claim of a divine commission to prepare for the second coming of Christ. -

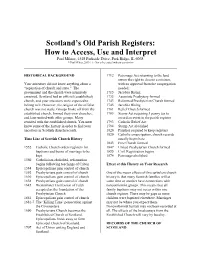

Scotland's Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret

Scotland’s Old Parish Registers: How to Access, Use and Interpret Paul Milner, 1548 Parkside Drive, Park Ridge, IL 6068 © Paul Milner, 2003-11 - Not to be copied without permission HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1712 Patronage Act returning to the land owner the right to choose a minister, Your ancestors did not know anything about a with no approval from the congregation “separation of church and state.” The needed. government and the church were intimately 1715 Jacobite Rising entwined. Scotland had an official (established) 1733 Associate Presbytery formed church, and your ancestors were expected to 1743 Reformed Presbyterian Church formed belong to it. However, the religion of the official 1745 Jacobite Rising church was not static. Groups broke off from the 1761 Relief Church formed established church, formed their own churches, 1783 Stamp Act requiring 3 penny tax to and later united with other groups. Many record an event in the parish register reunited with the established church. You must 1793 Catholic Relief Act know some of the history in order to find your 1794 Stamp Act abolished ancestors in Scottish church records. 1820 Parishes required to keep registers 1829 Catholic emancipation, church records Time Line of Scottish Church History usually begin here 1843 Free Church formed 1552 Catholic Church orders registers for 1847 United Presbyterian Church formed baptisms and banns of marriage to be 1855 Civil Registration begins kept 1874 Patronage abolished 1560 Catholicism abolished, reformation begins following teachings of Calvin Effect of this History on Your Research 1584 Episcopalians gain control of church 1592 Presbyterians gain control of church One of the major effects of this turbulent church 1610 Episcopalians gain control of church history is that many Scottish families will at 1638 Presbyterians gain control of church some time or another have connections with 1645 Westminster Confession of Faith nonconformist groups. -

A Singular Solace: an Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000

A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 David William Dutton BA, MTh October 2020 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Stirling for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History. Division of History and Politics 1 Research Degree Thesis Submission Candidates should prepare their thesis in line with the code of practice. Candidates should complete and submit this form, along with a soft bound copy of their thesis for each examiner, to: Student Services Hub, 2A1 Cottrell Building, or to [email protected]. Candidate’s Full Name: DAVID WILLIAM DUTTON Student ID: 2644948 Thesis Word Count: 49,936 Maximum word limits include appendices but exclude footnotes and bibliographies. Please tick the appropriate box MPhil 50,000 words (approx. 150 pages) PhD 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by publication) 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by practice) 40,000 words (approx. 120 pages) Doctor of Applied Social Research 60,000 words (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Business Administration 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Education 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Midwifery / Nursing / Professional Health Studies 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Diplomacy 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Thesis Title: A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 Declaration I wish to submit the thesis detailed above in according with the University of Stirling research degree regulations. I declare that the thesis embodies the results of my own research and was composed by me. Where appropriate I have acknowledged the nature and extent of work carried out in collaboration with others included in the thesis. -

History of the Presbyterian Churches of the World, Adapted for Use in the Class Room

History of the Presbyterian Churches of the World Adapted for use in the Class Room BY R. C. REED D. D. Professor of Church History in the Presbyterian Theological Seminary at Columbia, South Carolina; author of •• The Gospel as Taught by Calvin." PHILADELPHIA Zbe TKIlestminster press 1912 BK ^71768 Copyright. 1905, by The Trustees of the I'resbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work. Contents CHAPTER PAGE I INTRODUCTION I II SWITZERLAND 14 III FRANCE 34 IV THE NETHERLANDS 72 V AUSTRIA — BOHEMIA AND MORAVIA . 104 VI SCOTLAND 126 VII IRELAND 173 VIII ENGLAND AND WALES 205 IX THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA . 232 X UNITED STATES (Continued) 269 XI UNITED STATES (Continued) 289 XII UNITED STATES (Continued) 301 XIII UNITED STATES (Continued) 313 XIV UNITED STATES (Continued) 325 • XV CANADA 341 XVI BRITISH COLONIAL CHURCHES .... 357 XVII MISSIONARY TERRITORY 373 APPENDIX 389 INDEX 405 iii History of the Presbyterian Churches CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION WRITERS sometimes use the term Presbyterian to cover three distinct things, government, doctrine and worship ; sometimes to cover doctrine and government. It should be restricted to one thing, namely, Church Government. While it is usually found associated with the Calvinistic system of doctrine, yet this is not necessarily so ; nor is it, indeed, as a matter of fact, always so. Presbyterianism and Calvinism seem to have an affinity for one another, but they are not so closely related as to be essential to each other. They can, and occasionally do, live apart. Calvinism is found in the creeds of other than Presby terian churches ; and Presbyterianism is found professing other doctrines than Calvinism. -

The Emergence of Schism: a Study in the History of the Scottish Kirk from the National Covenant to the First Secession

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bilkent University Institutional Repository THE EMERGENCE OF SCHISM: A STUDY IN THE HISTORY OF THE SCOTTISH KIRK FROM THE NATIONAL COVENANT TO THE FIRST SECESSION A Master’s Thesis by RAVEL HOLLAND Department of History İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara September 2014 To Cadoc, for teaching me all the things that didn’t happen. THE EMERGENCE OF SCHISM: A STUDY IN THE HISTORY OF THE SCOTTISH KIRK FROM THE NATIONAL COVENANT TO THE FIRST SECESSION Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by RAVEL HOLLAND In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2014 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. ----------------------------- Assoc. Prof. Cadoc Leighton Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. ----------------------------- Asst. Prof. Paul Latimer Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. ----------------------------- Asst. Prof. Daniel P. Johnson Examining Committee Member Approval of the Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences ----------------------------- Prof. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 {\ C, - U 7 (2» OMB NoJU24,0018 (Rev. 10-90) ^ 2280 Ktw^-^J^.———\ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. sW-irTSffuctions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name _____Lower Long Cane Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church and Cemetery other names/site number Long Cane Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church and Cemetery 2. Location street & number 4 miles west of Trov on SR 33-36_______________ not for publication __ city or town Trov___________________________________ vicinity __X state South Carolina code SC county McCormick______ code 065 zip code 29848 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _ nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The Interaction of Scottish and English Evangelicals

THE INTERACTION OF SCOTTISH AND ENGLISH EVANGELICALS 1790 - 1810 Dudley Reeves M. Litt. University of Glasgov 1973 ProQuest Number: 11017971 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11017971 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to the following: The Rev. Ian A. Muirhead, M.A., B.D. and the Rev. Garin D. White, B.A., B.D., Ph.D. for their most valuable guidance and criticism; My wife and daughters for their persevering patience and tolerance The staff of several libraries for their helpful efficiency: James Watt, Greenock; Public Central, Greenock; Bridge of Weir Public; Trinity College, Glasgow; Baptist Theological College, Glasgow; University of Glasgow; Mitchell, Glasgow; New College, Edinburgh; National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh; General Register House, Edinburgh; British Museum, London; Sion College, London; Dr Williams's, London. Abbreviations British and Foreign Bible Society Baptist Missionary Society Church Missionary Society London Missionary Society Ii§I I Ii§I Society for Propagating the Gospel at Home SSPCK Scottish Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge CONTENTS 1. -

CHAPTER 4 the 18TH-CENTURY SCOTTISH SERMON : Bk)DES of RHETORIC Ýý B

r CHAPTER 4 THE 18TH-CENTURY SCOTTISH SERMON: bk)DES OF RHETORIC B ýý 18f G Z c9. ;CJ . 'f 259. TILE 18TH-CENTURY SCOTT ISi1 SERMON: )JODES OF RHETORIC Now-a-days, a play, a real or fictitious history, or a romance, however incredible and however un- important the subject may be with regard to the beat interests of men, and though only calculated to tickle a volatile fancy, arcImore valued than the best religious treatise .... This statement in the preface to a Scottish Evangelical tract of the 1770s assembles very clearly the reaction in Evangelical circles to contemporary trends in 18th-century Scottish letters, The movement in favour of a less concen- trated form of religion and the attractions of the new vogue for elegant and melodic sermons were regarded by the majority of Evangelicals as perilous innovations. From the 1750s onwards, the most important task facing Moderate sermon- writers was how to blend the newly-admired concepts of fine feeling and aesthetic taste with a modicum of religious teaching. The writers of Evangelical sermons, on the other hand, remained faithful to the need to restate the familiar tenets of doctrinal faith, often to the exclusion of all else. The Evangelicals regarded the way in which Moderate divines courted fine feeling in their pulpits as both regrettable and ominous. In some quarters, it even assumed the character of a possible harbinger of doom for Scottish prosperity. This reaction on the part of the Evangelicals accounts for the frequent 'alarms' published in connexion with religious topics in 18th-century Scotland. -

The Erskine Halcro Genealogy

u '^A. cpC National Library of Scotland *B0001 37664* Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/erskinehalcrogen1890scot THE ERSKINE-HALCRO GENEALOGY PRINTED FEBRUARY I 895 Impression 250 copies Of which 210 are for sale THE Erskine-Halcro Genealogy THE ANCESTORS AND DESCENDANTS OF HENRY ERSKINE, MINISTER OF CHIRNSIDE, HIS WIFE, MARGARET HALCRO OF ORKNEY, AND THEIR SONS, EBENEZER AND RALPH ERSKINE BY EBENEZER ERSKINE SCOTT A DESCENDANT NEW EDITION, ENLARGED Thefortune of the family remains, And grandsires' grandsires the long list contains. Dryden'S Virgil : Georgic iv. 304. (5 I M EDINBURGH GEORGE P. JOHNSTON 33 GEORGE STREET 1895 Edinburgh : T. and A. Constable, Printers to Her Majesty CONTENTS PAGE Preface to Second Edition, ..... vii Introduction to the First Edition, .... ix List of some of the Printed Books and MSS. referred to, xviii Table I. Erskine of Balgownie and Erskine of Shielfield, I Notes to Table I., 5 Table II. Halcro of Halcro in Orkney, 13 Notes to Table II., . 17 Table III. Stewart of Barscube, Renfrewshire, 23 Notes to Table III., . 27 Table IV. Erskine of Dun, Forfarshire, 33 Notes to Table IV., 37 Table V. Descendants of the Rev. Henry Erskine, Chirnside— Part I. Through his Older Son, Ebenezer Erskine of Stirling, . 41 Part II. Through his Younger Son, Ralph Erskine of Dunfermline, . 45 Notes to Table V., Parts I. and II., 49 — PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION By the kind assistance of friends and contributors I have been enabled to rectify several mistakes I had fallen into, and to add some important information unknown to me in 1890 when the first edition was issued. -

Jeanette Currie-27072009.Pdf

JANETTE CURRE History, Hagiography, and Fakestory: Representations of the Scottsh Covenanters in Non-Fictional and Fictional Texts from 1638 to 1835 Submitted for the degree of Phd. 29th September, 1999 Department of English, University of Stirling, STIRLING. FK94LA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to Drs. David Reid and Douglas Mack who shared the supervision of my disserttion. I would also like to record my thans to the varous libraries that have assisted me in the course of my studies; the staff at both the National Librar of Scotland and the Mitchell Librar in Glasgow were paricularly helpfuL. To my family, I am indebted for their patience. CONTENTS PAGE List of Abbreviations 1 List of Illustrations 11 Introduction 11 CHATER ONE 1 Representations and Misrepresentations of the Scottish Covenanters from 1638 to 1688 CHATER TWO 58 Discordant Discourses: Representations of the Scottish Covenanters in the eighteenth century CHATER THRE 108 "The Hoop of Rags": Scott's Notes As National History CHATER FOUR 166 Scott's anti-Covenanting satire CHATER FIVE 204 Unquiet Graves: Representations of the Scottish ConclusionCovenanters from 1817 to 1835 258 APPENDIX 261 'The Fanaticks New-Covenant' BIBLIOGRAHY 271 LIST OF ABBREVITIONS The Brownie The Brownie ofBodsbeck and other tales The Minstrelsy Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border W Waverley TOM The Tale of Old Mortality HoM The Heart of Midlothian LWM A Legend of the Wars ofMontrose ME The Mountain Bard TWM Tales of the Wars of Montrose 11 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ' 1. Title page of A Sermon Preached at Glasgow' (1679?) p.41a 2. The front-piece to the first edition of A Hind Let Loose (1687) p.53a 3. -

The Forgotten General

FOR REFERENCE Do Not Take From This Room 9 8 1391 3 6047 09044977 7 REF NJ974.9 HFIIfnKi.% SSf?rf?ttr" rn.fg f ° United St.?.. The Forgotten General BY ALBERT H. HEUSSER,* PATERSON, NEW JERSEY Foreword—We have honored Lafayette, Pulaski and Von Steu- ben, but we have forgotten Erskine. No monument, other than a tree planted by Washington beside his gravestone at Ringwood, N. J., has ever been erected to the memory of the noble young Scotchman who did so much to bring the War of the Revolution to a successful issue. Robert Erskine, F. R. S., the Surveyor-General of the Conti- nental Army and the trusted friend of the Commander-in-chief, was the silent man behind the scenes, who mapped out the by-ways and the back-roads over the mountains, and—by his familiarity with the great "middle-ground" between the Hudson Highlands and the Delaware—provided Washington with that thorough knowledge of the topography of the country which enabled him repeatedly to out- maneuver the enemy. It is a rare privilege to add a page to the recorded history of the American struggle for independence, and an added pleasure thereby to do justice to the name of one who, born a subject of George III, threw in his lot with the champions of American lib- erty. Although never participating in a battle, he was the means of winning many. He lost his life and his fortune for America; naught was his reward save a conscience void of offense, and the in- *Mr.