Diversity, Endemism and Evolution of the Australian Insect Fauna: Examples from Select Orders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Prairie Restoration on Hemiptera

CAN THE ONE TRUE BUG BE THE ONE TRUE ANSWER? THE INFLUENCE OF PRAIRIE RESTORATION ON HEMIPTERA COMPOSITION Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Science in Biology By Stephanie Kay Gunter, B.A. Dayton, Ohio August 2021 CAN THE ONE TRUE BUG BE THE ONE TRUE ANSWER? THE INFLUENCE OF PRAIRIE RESTORATION ON HEMIPTERA COMPOSITION Name: Gunter, Stephanie Kay APPROVED BY: Chelse M. Prather, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor Associate Professor Department of Biology Ryan W. McEwan, Ph.D. Committee Member Associate Professor Department of Biology Mark G. Nielsen Ph.D. Committee Member Associate Professor Department of Biology ii © Copyright by Stephanie Kay Gunter All rights reserved 2021 iii ABSTRACT CAN THE ONE TRUE BUG BE THE ONE TRUE ANSWER? THE INFLUENCE OF PRAIRIE RESTORATION ON HEMIPTERA COMPOSITION Name: Gunter, Stephanie Kay University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Chelse M. Prather Ohio historically hosted a patchwork of tallgrass prairies, which provided habitat for native species and prevented erosion. As these vulnerable habitats have declined in the last 200 years due to increased human land use, restorations of these ecosystems have increased, and it is important to evaluate their success. The Hemiptera (true bugs) are an abundant and varied order of insects including leafhoppers, aphids, cicadas, stink bugs, and more. They play important roles in grassland ecosystems, feeding on plant sap and providing prey to predators. Hemipteran abundance and composition can respond to grassland restorations, age of restoration, and size and isolation of habitat. -

The Planthopper Genus <I>Acanalonia </I>In the United

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida September 1995 The planthopper genus Acanalonia in the United States (Homoptera: Issidae): male and female genitalic morphology Rebecca Freund University of South Dakota, Vermillion, SD Stephen W. Wilson Central Missouri State University, Warrensburg, MO Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Entomology Commons Freund, Rebecca and Wilson, Stephen W., "The planthopper genus Acanalonia in the United States (Homoptera: Issidae): male and female genitalic morphology" (1995). Insecta Mundi. 133. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/133 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 9, No. 3-4, September - December, 1995 195 The planthopper genus Acanalonia in the United States (Homoptera: Issidae): male and female genitalic morphology Rebecca Freund Department of Biology, University of South Dakota, Vermillion, SD 57069 and Stephen W. Wilson Department of Biology, Central Missouri State University, Warrensburg, MO 64093 Abstract: The issidplanthopper genus Acanalonia is reviewed anda key to the 18 speciesprovided. Detailed descriptions and illustrationsof the complete external morphology ofA. conica (Say), anddescriptionsandillustrationsof the male and female external genitalia ofthe species ofunited States Acanalonia are given. The principal genitalic features usedto separate species included: male - shape andlength ofthe aedeagalcaudal andlateralprocesses, and presence ofcaudalextensions; female -shape ofthe 8th abdominal segment and the number of teeth on the gonapophysis ofthe 8th segment. -

Food Load Manipulation Ability Shapes Flight Morphology in Females Of

Polidori et al. Frontiers in Zoology 2013, 10:36 http://www.frontiersinzoology.com/content/10/1/36 RESEARCH Open Access Food load manipulation ability shapes flight morphology in females of central-place foraging Hymenoptera Carlo Polidori1*, Angelica Crottini2, Lidia Della Venezia3,5, Jesús Selfa4, Nicola Saino5 and Diego Rubolini5 Abstract Background: Ecological constraints related to foraging are expected to affect the evolution of morphological traits relevant to food capture, manipulation and transport. Females of central-place foraging Hymenoptera vary in their food load manipulation ability. Bees and social wasps modulate the amount of food taken per foraging trip (in terms of e.g. number of pollen grains or parts of prey), while solitary wasps carry exclusively entire prey items. We hypothesized that the foraging constraints acting on females of the latter species, imposed by the upper limit to the load size they are able to transport in flight, should promote the evolution of a greater load-lifting capacity and manoeuvrability, specifically in terms of greater flight muscle to body mass ratio and lower wing loading. Results: Our comparative study of 28 species confirms that, accounting for shared ancestry, female flight muscle ratio was significantly higher and wing loading lower in species taking entire prey compared to those that are able to modulate load size. Body mass had no effect on flight muscle ratio, though it strongly and negatively co-varied with wing loading. Across species, flight muscle ratio and wing loading were negatively correlated, suggesting coevolution of these traits. Conclusions: Natural selection has led to the coevolution of resource load manipulation ability and morphological traits affecting flying ability with additional loads in females of central-place foraging Hymenoptera. -

New Species of Aenetus from Sumatra, Indonesia (Lepidoptera

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Entomofauna Jahr/Year: 2018 Band/Volume: 0039 Autor(en)/Author(s): Grehan John R., Witt Thomas Josef, Ignatyev Nikolay N. Artikel/Article: New Species of Aenetus from Sumatra, Indonesia (Lepidoptera: Hepialidae) and a 5,000 km biogeographic disjunction 849-862 Entomofauna 39/239/1 HeftHeft 19:##: 849-862000-000 Ansfelden, 31.2. Januar August 2018 2018 New Species of Aenetus from Sumatra, Indonesia (Lepidoptera: Hepialidae) and a 5,000 km biogeographic disjunction John R. GREHAN, THOMAS J. WITT & NIKOLAI IGNATEV Abstract Discovery of Aenetus sumatraensis nov.sp. from northern Sumatra expands the distribution range of this genus well into southeastern Asia along the Greater and Lesser Sunda. The species belongs to the A. tegulatus clade distributed between northern Australia, New Gui- nea, islands west of New Guinea and the Lesser Sunda that are separated by over 5,000 km from A. sumatraensis nov.sp.. The Sumatran record either represents local differentiation from a formerly widespread ancestor or it is part a larger distribution of the A. tegulatus clade in the Greater Sunda that has not yet been discovered. The bursa copulatrix of the Australian species referred to as A. tegulatus is different from specimens examined in New Guinea and Ambon Islands (locality for the type) and is therefore referred to here as A. ther- mistes stat.rev. Zusammenfassung Die Entdeckung von Aenetus sumatraensis nov.sp. in Nord-Sumatra dehnt das Verbreitungs- gebiet dieser Gattung aus bis nach Südostasien entlang der Großen und Kleinen Sundainseln. -

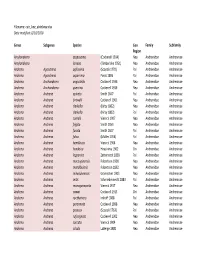

Anthophila List

Filename: cuic_bee_database. -

A Monographic Revision of the Genus Platycoelia Dejean (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Rutelinae: Anoplognathini) Andrew B

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Bulletin of the University of Nebraska State Museum, University of Nebraska State Museum 2003 A Monographic Revision of the Genus Platycoelia Dejean (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Rutelinae: Anoplognathini) Andrew B. T. Smith University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumbulletin Part of the Entomology Commons, and the Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Smith, Andrew B. T., "A Monographic Revision of the Genus Platycoelia Dejean (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Rutelinae: Anoplognathini)" (2003). Bulletin of the University of Nebraska State Museum. 3. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumbulletin/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletin of the University of Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A Monographic Revision of the Genus Platycoelia Dejean (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Rutelinae: Anoplognathini) Andrew B. T. Smith Bulletin of the University of Nebraska State Museum Volume 15 A Monographic Revision of the Genus Platycoelia Dejean (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Rutelinae: Anoplognathini) by Andrew B. T. Smith UNIVERSITY. OF, ( NEBRASKA "-" STATE MUSEUM Published by the University of Nebraska State Museum Lincoln, Nebraska 2003 Bulletin of the University of Nebraska State Museum Volume 15 Issue Date: 7 July 2003 Editor: Brett C. Ratcliffe Cover Design: Angie Fox Text design and layout: Linda J. Ratcliffe Text fonts: New Century Schoolbook and Arial Bulletins may be purchased from the Museum. Address orders to: Publications Secretary W436 Nebraska Hall University of Nebraska State Museum Lincoln, NE 68588-0514 U.S.A. -

Check List of the Rutelinae (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae) of Oceania

CHECK LIST OF THE RUTELINAE (COLEOPTERA, SCARABAEIDAE) OF OCEANIA By FRIEDRICH OHAUS BERNICE P. BISHOP MUSEUM OCCASIONAL PAPERS VOLUME XI, NUMBER 2 HONOLULU, HAWAII PUBLISHED BY THE MUSJ-:UM 1935 CHECK LIST OF THE RUTELINAE (COLEOPTERA, SCARABAEIDAE) OF OCEANIA By FRIEDRICH OHAUS MAINZ, GERMANY BIOLOGY The RuteIinae are plant feeders. In Parastasia the beetle (imago) visits flowers, and the grub (larva) lives in dead trunks of more or less hard wood. In Anomala the beetle is a leaf feeder, and the grub lives in the earth, feeding on the roots of living plants. In Adoretus the beetle feeds on flowers and leaves; the grub lives in the earth and feeds upon the roots of living plants. In some species of Anornala and Adoretus, both beetles and grubs are noxious to culti vated plants, and it has been observed that eggs or young grubs of these species have been transported in the soil-wrapping around roots or parts of roots of such plants as the banana, cassava, and sugar cane. DISTRIBUTION With the exception of two species, the Rutelinae found on the continent of Australia (including Tasmania) belong to the subtribe Anoplognathina. The first exception is Anomala (Aprosterna) antiqua Gyllenhal (australasiae Blackburn), found in northeast Queensland in cultivated places near the coast. This species is abundant from British India and southeast China in the west to New Guinea in the east, stated to be noxious here and there to cultivated plants. It was probably brought to Queensland by brown or white men, as either eggs or young grubs in soil around roots of bananas, cassava, or sugar cane. -

The Mcguire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity

Supplemental Information All specimens used within this study are housed in: the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity (MGCL) at the Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, USA (FLMNH); the University of Maryland, College Park, USA (UMD); the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris, France (MNHN); and the Australian National Insect Collection in Canberra, Australia (ANIC). Methods DNA extraction protocol of dried museum specimens (detailed instructions) Prior to tissue sampling, dried (pinned or papered) specimens were assigned MGCL barcodes, photographed, and their labels digitized. Abdomens were then removed using sterile forceps, cleaned with 100% ethanol between each sample, and the remaining specimens were returned to their respective trays within the MGCL collections. Abdomens were placed in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes with the apex of the abdomen in the conical end of the tube. For larger abdomens, 5 mL microcentrifuge tubes or larger were utilized. A solution of proteinase K (Qiagen Cat #19133) and genomic lysis buffer (OmniPrep Genomic DNA Extraction Kit) in a 1:50 ratio was added to each abdomen containing tube, sufficient to cover the abdomen (typically either 300 µL or 500 µL) - similar to the concept used in Hundsdoerfer & Kitching (1). Ratios of 1:10 and 1:25 were utilized for low quality or rare specimens. Low quality specimens were defined as having little visible tissue inside of the abdomen, mold/fungi growth, or smell of bacterial decay. Samples were incubated overnight (12-18 hours) in a dry air oven at 56°C. Importantly, we also adjusted the ratio depending on the tissue type, i.e., increasing the ratio for particularly large or egg-containing abdomens. -

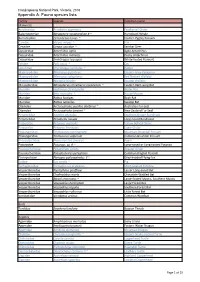

Report-VIC-Croajingolong National Park-Appendix A

Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, 2016 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Mammals Acrobatidae Acrobates pygmaeus Feathertail Glider Balaenopteriae Megaptera novaeangliae # ~ Humpback Whale Burramyidae Cercartetus nanus ~ Eastern Pygmy Possum Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox Cervidae Cervus unicolor ^ Sambar Deer Dasyuridae Antechinus agilis Agile Antechinus Dasyuridae Antechinus mimetes Dusky Antechinus Dasyuridae Sminthopsis leucopus White-footed Dunnart Felidae Felis catus ^ Cat Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropodidae Macropus rufogriseus Red Necked Wallaby Macropodidae Wallabia bicolor Swamp Wallaby Miniopteridae Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis ~ Eastern Bent-wing Bat Muridae Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Muridae Mus musculus ^ House Mouse Muridae Rattus fuscipes Bush Rat Muridae Rattus lutreolus Swamp Rat Otariidae Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus ~ Australian Fur-seal Otariidae Arctocephalus forsteri ~ New Zealand Fur Seal Peramelidae Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Peramelidae Perameles nasuta Long-nosed Bandicoot Petauridae Petaurus australis Yellow Bellied Glider Petauridae Petaurus breviceps Sugar Glider Phalangeridae Trichosurus cunninghami Mountain Brushtail Possum Phalangeridae Trichosurus vulpecula Common Brushtail Possum Phascolarctidae Phascolarctos cinereus Koala Potoroidae Potorous sp. # ~ Long-nosed or Long-footed Potoroo Pseudocheiridae Petauroides volans Greater Glider Pseudocheiridae Pseudocheirus peregrinus -

Erster Nachtrag Zur Mikrolepidopterenfauna Zyperns

©Entomologischer Verein Apollo e.V. Frankfurt am Main; download unter www.zobodat.at Nachr. entomol. Ver. Apollo, N.F. 17 (2): 209-224 (1996) 209 Erster Nachtrag zur Mikrolepidopterenfauna Zyperns Ernst Arenberger und Josef Wimmer Ernst A renberger, Börnergasse 3, 4/6, A-1190 Wien, Österreich Josef Wimmer, Feldstraße 3 D, A-4400 Steyr, Österreich Zusammenfassung: Vor allem durch die Aufsammlungen von J. Wimmer, Steyr, wird die Liste der von Zypern bekannten Mikrolepidopterenfauna um 35 Arten vermehrt und auf insgesamt 496 Taxa ergänzt. Schlüsselwörter: Insecta, Lepidoptera, Mikrolepidoptera, Systematik, Fauni- stik, palaearktische Region, Fauna Zyperns. First Supplement to the microlepidopteran fauna of Cyprus Abstract: The list of the species of microlepidoptera of Cyprus is increased from 461 species to 496 taxa now in total, especially by the collections of J. Wimmer, Steyr, Austria. Key words: Insecta, Lepidoptera, Microlepidoptera, systematics, faunistics, Palaearctic region, fauna of Cyprus. Einleitung Schon kurze Zeit nach Erscheinen der Zusammenfassung aller bisher ge meldeten Meldungen über die Mikrolepidopteren Zyperns (Arenberger 1995) liegen wieder zahlreiche noch unveröffentlichte Funde aus Zypern vor. Es handelt sich insbesondere um Aufsammlungen von J. Wimmer in den Jahren 1993-1995 in der Umgebung von Paphos. Die bisherigen Sam melergebnisse bezogen sich einerseits auf den Norden der Insel, der Um gebung von Kyrenia, und andererseits auf das gebirgige Zentrum im Troodos-Gebirge sowie das Küstengebiet des Südens (Karte siehe bei Arenberger 1995). Jetzt können auch Angaben über die Fauna des westli chen Teiles der Insel gemacht werden. Ergänzt wird der vorliegende Beitrag durch restliche Arten aus den Aus beuten K. Mikkolas und des Autors, die bei Arenberger (1995) nicht ein bezogen werden konnten, sowie einige Funde von R. -

Hymenoptera, Apoidea)

>lhetian JMfuseum ox4tates PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 2 2 24 AUGUST I7, I 965 The Biology and Immature Stages of Melitturga clavicornis (Latreille) and of Sphecodes albilabris (Kirby) and the Recognition of the Oxaeidae at the Family Level (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) BYJEROME G. ROZEN, JR.' Michener (1944) divided the andrenid subfamily Panurginae into two tribes, the Panurgini and Melitturgini, with the latter containing the single Old World genus Melitturga. This genus was relegated to tribal status apparently on the grounds that the adults, unlike those of other panurgines, bear certain striking resemblances to the essentially Neo- tropical Oxaeinae of the same family. In 1951 Rozen showed that the male genitalia of Melitturga are unlike those of the Oxaeinae and are not only typical of those of the Panurginae in general but quite like those of the Camptopoeum-Panurgus-Panurginus-Epimethea complex within the sub- family. On the basis of this information, Michener (1954a) abandoned the idea that the genus Melitturga represents a distinct tribe of the Panur- ginae. Recently evidence in the form of the larva of Protoxaea gloriosa Fox (Rozen, 1965) suggested that the Oxaeinae were so unlike other Andreni- dae that they should be removed from the family unless some form inter- 1 Chairman and Associate Curator, Department of Entomology, the American Museum of Natural History. 2 AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES NO. 2224 mediate between the two subfamilies is found. In spite of the structure of the male genitalia, Melitturga is the only known possible intermediary. -

Lepidoptera of the Tolman Bridge Area (2000-2011)

LEPIDOPTERA OF THE TOLMAN BRIDGE AREA, ALBERTA, 2000-2011 Charles Bird, 8 March 2012 Box 22, Erskine, AB T0C 1G0 [email protected] The present paper includes a number of redeterminations and additions to the information in earlier reports. It also follows the up-to-date order and taxonomy of Pohl et al. (2010), rather than that of Hodges et al. (1983). Brian Scholtens, Greg Pohl and Jean-François Landry collecting moths at a sheet illuminated by a mercury vapor (MV) light, Tolman Bridge, 24 July 2003, during the 2003 Olds meetings of the Lepidopterist’s Society (C.D. Bird image). Tolman Bridge, is located in the valley of the Red Deer River, 18 km (10 miles) east of the town of Trochu. The bridge and adjoining Park land are in the north half of section 14, range 22, township 34, west of the Fourth Meridian. The coordinates at the bridge are 51.503N and 113.009W. The elevation ranges from around 600 m at the river to 800 m or so near the top of the river breaks. In a Natural Area Inspection Report dated 25 June 1982 and in the 1989 Trochu 82 P/14, 1:50,000 topographic map, the land southwest of the bridge was designated as the “Tolman Bridge Municipal Park” while that southeast of the bridge was referred to as the “Tolman Bridge Recreation Area”. In an Alberta, Department of the Environment, Parks and Protected Areas Division paper dated 9 May 2000, the areas on both sides of the river are included in “Dry Island Buffalo Jump Provincial Park”.