Answer the Call

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DNR Letterhead

ATU F N RA O L T R N E E S M O T U STATE OF MICHIGAN R R C A P DNR E E S D MI N DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES CHIG A JENNIFER M. GRANHOLM LANSING REBECCA A. HUMPHRIES GOVERNOR DIRECTOR Michigan Frog and Toad Survey 2009 Data Summary There were 759 unique sites surveyed in Zone 1, 218 in Zone 2, 20 in Zone 3, and 100 in Zone 4, for a total of 1097 sites statewide. This is a slight decrease from the number of sites statewide surveyed last year. Zone 3 (the eastern half of the Upper Peninsula) is significantly declining in routes. Recruiting in that area has become necessary. A few of the species (i.e. Fowler’s toad, Blanchard’s cricket frog, and mink frog) have ranges that include only a portion of the state. As was done in previous years, only data from those sites within the native range of those species were used in analyses. A calling index of abundance of 0, 1, 2, or 3 (less abundant to more abundant) is assigned for each species at each site. Calling indices were averaged for a particular species for each zone (Tables 1-4). This will vary widely and cannot be considered a good estimate of abundance. Calling varies greatly with weather conditions. Calling indices will also vary between observers. Results from the evaluation of methods and data quality showed that volunteers were very reliable in their abilities to identify species by their calls, but there was variability in abundance estimation (Genet and Sargent 2003). -

American Toad (Anaxyrus Americanus) Fowler's Toad (Anaxyrus Fowleri

Vermont has eleven known breeding species of frogs. Their exact distributions are still being determined. In order for these species to survive and flourish, they need our help. One way you can help is to report the frogs that you come across in the state. Include in your report as much detail as you can on the appearance and location of the animal; also include the date of the sighting, your name, and how to contact you. Photographs are ideal, but not necessary. When attempting to identify a particular species, check at least three different field markings so that you can be sure of what it is. To contribute a report, you may use our website (www.vtherpatlas.org) or contact Jim Andrews directly at [email protected]. American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) American Toad (Anaxyrus americanus) The American Bullfrog is our largest frog and can reach 7 inches long. The Bullfrog is one of the three The American Toad is one of Vermont’s two toad species. Toads can be distinguished from other green-faced frogs in Vermont. It has a green and brown mottled body with dark stripes across its legs. frogs in Vermont by their dry and bumpy skin, and the long oval parotoid glands on each side of their The Bullfrog does not have dorsolateral ridges, but it does have a ridge that starts at the eye and goes necks. The American Toad has at least one large wart in each of the large black spots found along its around the eardrum (tympana) and down. The Bullfrog’s call is a deep low jum-a-rum. -

Species Status Assessment Report for the Eastern Population of The

Species Status Assessment Report for the Eastern Population of the Boreal Toad, Anaxyrus boreas boreas Prepared by the Western Colorado Ecological Services Field Office U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Grand Junction, Colorado EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This species status assessment (SSA) reports the results of the comprehensive biological status review by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) for the Eastern Population of the boreal toad (Anaxyrus boreas boreas) and provides a thorough account of the species’ overall viability and, therefore, extinction risk. The boreal toad is a subspecies of the western toad (Anaxyrus boreas, formerly Bufo boreas). The Eastern Population of the boreal toad occurs in southeastern Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, northern New Mexico, and most of Utah. This SSA Report is intended to provide the best available biological information to inform a 12-month finding and decision on whether or not the Eastern Population of boreal toad is warranted for listing under the Endangered Species Act (Act), and if so, whether and where to propose designating critical habitat. To evaluate the biological status of the boreal toad both currently and into the future, we assessed a range of conditions to allow us to consider the species’ resiliency, redundancy, and representation (together, the 3Rs). The boreal toad needs multiple resilient populations widely distributed across its range to maintain its persistence into the future and to avoid extinction. A number of factors influence whether boreal toad populations are considered resilient to stochastic events. These factors include (1) sufficient population size (abundance), (2) recruitment of toads into the population, as evidenced by the presence of all life stages at some point during the year, and (3) connectivity between breeding populations. -

Signs of the Seasons: a New England Phenology Program Indicator

Signs of the Seasons: A New England Phenology Program Indicator Species Fact Sheet Eastern American Toad, Anaxyrus americanus The American toad is commonly found throughout New England and is native to eastern North America. Considered habitat generalists, these toads can be found anywhere that moisture and ample food are available, including multiple forest types, fields and urban areas. Toads play an important ecosystem role as insect consumers, thereby keeping populations in check. Appearance: Toads are shades of brown in color and are covered with warts. They have a wide head and short front limbs. Behind the eyes, there are kidney bean shaped glands; J.D. Willson, USGS Savannah River Ecology Lab, http://srel.uga.edu/ these paratoid glands produce toxins that give the toad an unpleasant taste. The toads range in length from 2-4 ½ inches. Females are slightly larger than males and lack the characteristic dark colored throat seen on males. Feeding: American toads are known to feed from early morning into the evening. They consume what is available and may eat a variety of larval insects, slugs, spiders, and centipedes, for example. Tadpoles feed on algae within their pools. Life History: Breeding season is triggered by the arrival of warmer temperatures and longer days. It begins in March or April when the toads arrive at shallow, fresh water pools. Males grasp the females around the belly in order to fertilize the eggs as they are laid. Between 4,000-12,000 eggs are laid in long parallel strands. They will hatch in 3-12 days, requiring 5-10 weeks to complete metamorphosis and 2-4 years to reach sexual maturity. -

Wildlife in Your Young Forest.Pdf

WILDLIFE IN YOUR Young Forest 1 More Wildlife in Your Woods CREATE YOUNG FOREST AND ENJOY THE WILDLIFE IT ATTRACTS WHEN TO EXPECT DIFFERENT ANIMALS his guide presents some of the wildlife you may used to describe this dense, food-rich habitat are thickets, T see using your young forest as it grows following a shrublands, and early successional habitat. timber harvest or other management practice. As development has covered many acres, and as young The following lists focus on areas inhabited by the woodlands have matured to become older forest, the New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis), a rare amount of young forest available to wildlife has dwindled. native rabbit that lives in parts of New York east of the Having diverse wildlife requires having diverse habitats on Hudson River, and in parts of Connecticut, Rhode Island, the land, including some young forest. Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire, and southern Maine. In this region, conservationists and landowners In nature, young forest is created by floods, wildfires, storms, are carrying out projects to create the young forest and and beavers’ dam-building and feeding. To protect lives and shrubland that New England cottontails need to survive. property, we suppress floods, fires, and beaver activities. Such projects also help many other kinds of wildlife that Fortunately, we can use habitat management practices, use the same habitat. such as timber harvests, to mimic natural disturbance events and grow young forest in places where it will do the most Young forest provides abundant food and cover for insects, good. These habitat projects boost the amount of food reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals. -

Frogs and Toads Defined

by Christopher A. Urban Chief, Natural Diversity Section Frogs and toads defined Frogs and toads are in the class Two of Pennsylvania’s most common toad and “Amphibia.” Amphibians have frog species are the eastern American toad backbones like mammals, but unlike mammals they cannot internally (Bufo americanus americanus) and the pickerel regulate their body temperature and frog (Rana palustris). These two species exemplify are therefore called “cold-blooded” (ectothermic) animals. This means the physical, behavioral, that the animal has to move ecological and habitat to warm or cool places to change its body tempera- similarities and ture to the appropriate differences in the comfort level. Another major difference frogs and toads of between amphibians and Pennsylvania. other animals is that amphibians can breathe through the skin on photo-Andrew L. Shiels L. photo-Andrew www.fish.state.pa.us Pennsylvania Angler & Boater • March-April 2005 15 land and absorb oxygen through the weeks in some species to 60 days in (plant-eating) beginning, they have skin while underwater. Unlike reptiles, others. Frogs can become fully now developed into insectivores amphibians lack claws and nails on their developed in 60 days, but many (insect-eaters). Then they leave the toes and fingers, and they have moist, species like the green frog and bullfrog water in search of food such as small permeable and glandular skin. Their can “overwinter” as tadpoles in the insects, spiders and other inverte- skin lacks scales or feathers. bottom of ponds and take up to two brates. Frogs and toads belong to the years to transform fully into adult Where they go in search of this amphibian order Anura. -

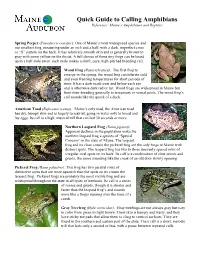

Quick Guide to Calling Amphibians Reference: Maine’S Amphibians and Reptiles

Quick Guide to Calling Amphibians Reference: Maine’s Amphibians and Reptiles Spring Peeper (Pseudacris crucifer): One of Maine’s most widespread species and our smallest frog, measuring under an inch and a half, with a dark, imperfect cross or “X” pattern on the back. It has relatively smooth skin and is generally brown to gray with some yellow on the throat. A full chorus of these tiny frogs can be heard up to a half-mile away; each male makes a shrill, pure, high-pitched breeding call. Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica): The first frog to emerge in the spring, the wood frog can tolerate cold and even freezing temperatures for short periods of ©USGS NEARMI time. It has a dark mask over and below each eye ©USGS NEARMI and is otherwise dark red or tan. Wood frogs are widespread in Maine but limit their breeding generally to temporary or vernal pools. The wood frog’s call sounds like the quack of a duck. ©James Hardy ©James Hardy American Toad (Bufo americanus): Maine’s only toad, the American toad has dry, bumpy skin and is largely terrestrial, going in water only to breed and lay eggs. Its call is a high, musical trill that can last 30 seconds or more. Northern Leopard Frog (Rana pipiens): Apparent declines in the population make the northern leopard frog a species of “Special Concern” in the state of Maine. The leopard frog and its close cousin the pickerel frog are the only frogs in Maine with distinct spots. The leopard frog has two to three unevenly spaced rows of irregular oval spots on its back. -

Yosemite Toad Conservation Assessment

United States Department of Agriculture YOSEMITE TOAD CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT A Collaborative Inter-Agency Project Forest Pacific Southwest R5-TP-040 January Service Region 2015 YOSEMITE TOAD CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT A Collaborative Inter-Agency Project by: USDA Forest Service California Department of Fish and Wildlife National Park Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Technical Coordinators: Cathy Brown USDA Forest Service Amphibian Monitoring Team Leader Stanislaus National Forest Sonora, CA [email protected] Marc P. Hayes Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Research Scientist Science Division, Habitat Program Olympia, WA Gregory A. Green Principal Ecologist Owl Ridge National Resource Consultants, Inc. Bothel, WA Diane C. Macfarlane USDA Forest Service Pacific Southwest Region Threatened Endangered and Sensitive Species Program Leader Vallejo, CA Amy J. Lind USDA Forest Service Tahoe and Plumas National Forests Hydroelectric Coordinator Nevada City, CA Yosemite Toad Conservation Assessment Brown et al. R5-TP-040 January 2015 YOSEMITE TOAD WORKING GROUP MEMBERS The following may be the contact information at the time of team member involvement in the assessment. Becker, Dawne Davidson, Carlos Harvey, Jim Associate Biologist Director, Associate Professor Forest Fisheries Biologist California Department of Fish and Wildlife Environmental Studies Program Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest 407 West Line St., Room 8 College of Behavioral and Social Sciences USDA Forest Service Bishop, CA 93514 San Francisco State University 1200 Franklin Way (760) 872-1110 1600 Holloway Avenue Sparks, NV 89431 [email protected] San Francisco, CA 94132 (775) 355-5343 (415) 405-2127 [email protected] Boiano, Daniel [email protected] Aquatic Ecologist Holdeman, Steven J. Sequoia/Kings Canyon National Parks Easton, Maureen A. -

Exotic and Invasive Alien Species in Newfoundland and Labrador

EXOTIC SPECIES: For More Information: Exotic and Invasive Alien Species Plants, animals and micromicro----organismsorganisms in Newfoundland and Labrador existing in habitats beyond their natural distribution. Their introduction is Department of Environment and usually caused by humans or human Conservation activities but most do not become Wildlife Division Newfoundland and Labrador is home to tens of invasive. Exotic species are also referred to Endangered Species and Biodiversity thousands of animals, plants, and other organisms. as introduced, nonnon----native,native, alien and nonnon---- Phone: (709) 637-2026 Together, these species create the unique indigenous species. www.gov.nl.ca/ environment and diverse habitats of the province. INVASIVE ALIEN SPECIES: However, intentionally or accidentally, exotic Botanical Gardens of Memorial University species have been introduced to the province. Harmful exotic species whose Memorial University of Newfoundland and While most exotics may have little or no impact on introduction or spread threatens the Labrador Cabbage White, S. Pardy Moores local ecosystems, some species may become environment, economy, or society, Phone: (709) 737-8590 www.mun.ca/botgarden invasive. including human health. PATHWAYS OF INTRODUCTION: Exotic and Canadian Biodiversity Network The activity, most commonly human, www.cbin.ec.gc.ca that provides the opportunity for species to establish in new habitats. Wild Species 2005 Invasive Alien www.wildspecies.ca THREATS: IAS Concepts, Terms & Context, CAB The potential negative outcomes to a http://www.cabi.org/ias_ctc.asp?Heading=Terms Species in habitat or species after the introduction of an exotic species. Threats include IUCN 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species biodiversity loss, introduction of www.issg.org/database Newfoundland Snowshoe Hare Coltsfoot predators, and loss of food source. -

Peatlands Many Wildlife Species Use Peatlands for Part of Their Life Cycle, Whether for Breeding, Feeding, Species Focus Cover Or Nesting

Wildlife found in peatlands Many wildlife species use peatlands for part of their life cycle, whether for breeding, feeding, Species Focus cover or nesting. Below are some examples of species that depend on peatland habitats. Be on of conservation concern the lookout for these species and other wildlife associated with peatlands. Follow stewardship guidelines to help maintain or enhance peatlands. Species of conservation concern--those wildlife Bog Lemming species identified in the Wildlife Action Plan as having the greatest need of conservation--appear in There are two species of bog lemming found in Bog Lemming New Hampshire: northern (which is very rare) and bold typeface. southern. Both have very short tails, distinguishing them from voles and other small rodents. They inhabit peatlands, digging burrows 6-12” beneath · Blanding’s turtle** · Ribbon snake the peat. They also build runways through surface · Eastern towhee · Ringed boghaunter dragonfly** vegetation, which they use for foraging on the · Mink frog · Rusty blackbird tender parts of grasses and sedges (look for · Southern bog lemming · Spotted turtle* distinctive piles of bright green fecal pellets). In · Northern bog lemming · Spruce grouse the summer, bog lemmings may nest in surface Palm warbler · runways instead of underground nests, making * state-threatened species them particularly vulnerable to trampling. Lemming ** state-endangered species populations fluctuate greatly and are poorly understood. Rusty Blackbird Where to get help If you have information about a wildlife species of conservation concern, contact NH Fish & Game’s Wildlife Rusty Blackbird Division at 603-271-2461. Contact the UNH Cooperative Extension Wildlife Specialist at 603-862-3594 for Rusty blackbirds are a northern species (e.g. -

Chirp, Croak, and Snore

MINNESOTA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER Young Naturalists Teachers Guide Prepared by “Chirp, Croak, and Snore” Multidisciplinary Jack Judkins, Classroom Activities Curriculum Teachers guide for the Young Naturalists article “Chirp, Croak, and Snore” by Mary Hoff. Connections Published in the March–April 2014 Minnesota Conservation Volunteer, or visit www.dnr.state.mn.us/young_naturalists/frogs-and-toads-of-minnesota/index.html. Minnesota Young Naturalists teachers guides are provided free of charge to classroom teachers, parents, and students. This guide contains a brief summary of the article, suggested independent reading levels, word count, materials list, estimates of preparation and instructional time, academic standards applications, preview strategies and study questions overview, adaptations for special needs students, assessment options, extension activities, Web resources (including related Minnesota Conservation Volunteer articles), copy-ready study questions with answer key, and a copy-ready vocabulary sheet and vocabulary study cards. There is also a practice quiz (with answer key) in Minnesota Comprehensive Assessments format. Materials may be reproduced and/or modified to suit user needs. Users are encouraged to provide feedback through an online survey at www.mndnr.gov/education/teachers/activities/ynstudyguides/survey.html. *All Minnesota Conservation Volunteer articles published since 1940 are now online in searchable PDF format. Visit www.mndnr.gov/magazine and click on past issues. Summary “Chirp, Croak, and Snore” surveys -

Forest Hill FIELD GUIDE

Forest Hill FIELD GUIDE FOREST HILL ALMA COLLEGE GIRESD ii • Forest Hill History • Forest Hill Nature Area www.GratiotConservationDistrict.org Forest Hill Nature Area, located in northern Gratiot County, Michigan, is land that has been set aside for the preservation and appreciation of the natural world. The nature area has walking trails through 90 acres of gently rolling hills, open fields, wetlands, Let children walk with nature. Let them see the beautiful blendings willow thickets, and woodlots. Forest Hill Nature Area is home to a and communions of death and life. Their joys inseparable unity. As variety of wildlife such as white-tailed deer, muskrats, ducks and taught in woods and meadows. Plains and mountains. And turkeys. streams. -John Muir Also, over the years, some farm buildings were demolished while others were renovated. The Nature Area has evolved into an Forest Hill Nature Area: important outdoor educational resource for the school children in Gratiot and Isabella Counties as well as the citizens of Mid- In 1992, the Gratiot County Soil Conservation District acquired a Michigan. Since 1993, thousands of school children and adults 90 acre abandoned farm from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. have participated in field trips and nature programs at Forest Hill In 1993, the District leased the property to the Gratiot-Isabella Nature Area. RESD to develop an outdoor education center. The RESD named the property, the Forest Hill Nature Area and in partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began a major wetland restoration project. 3 Digital Nature Trail Forest Hill is brimming with biodiversity and all it entails: succession, evolution, adaptation, wildlife and food chains.