Peatlands Many Wildlife Species Use Peatlands for Part of Their Life Cycle, Whether for Breeding, Feeding, Species Focus Cover Or Nesting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DNR Letterhead

ATU F N RA O L T R N E E S M O T U STATE OF MICHIGAN R R C A P DNR E E S D MI N DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES CHIG A JENNIFER M. GRANHOLM LANSING REBECCA A. HUMPHRIES GOVERNOR DIRECTOR Michigan Frog and Toad Survey 2009 Data Summary There were 759 unique sites surveyed in Zone 1, 218 in Zone 2, 20 in Zone 3, and 100 in Zone 4, for a total of 1097 sites statewide. This is a slight decrease from the number of sites statewide surveyed last year. Zone 3 (the eastern half of the Upper Peninsula) is significantly declining in routes. Recruiting in that area has become necessary. A few of the species (i.e. Fowler’s toad, Blanchard’s cricket frog, and mink frog) have ranges that include only a portion of the state. As was done in previous years, only data from those sites within the native range of those species were used in analyses. A calling index of abundance of 0, 1, 2, or 3 (less abundant to more abundant) is assigned for each species at each site. Calling indices were averaged for a particular species for each zone (Tables 1-4). This will vary widely and cannot be considered a good estimate of abundance. Calling varies greatly with weather conditions. Calling indices will also vary between observers. Results from the evaluation of methods and data quality showed that volunteers were very reliable in their abilities to identify species by their calls, but there was variability in abundance estimation (Genet and Sargent 2003). -

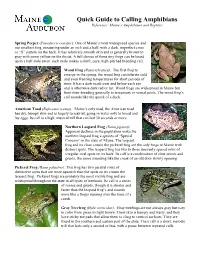

Quick Guide to Calling Amphibians Reference: Maine’S Amphibians and Reptiles

Quick Guide to Calling Amphibians Reference: Maine’s Amphibians and Reptiles Spring Peeper (Pseudacris crucifer): One of Maine’s most widespread species and our smallest frog, measuring under an inch and a half, with a dark, imperfect cross or “X” pattern on the back. It has relatively smooth skin and is generally brown to gray with some yellow on the throat. A full chorus of these tiny frogs can be heard up to a half-mile away; each male makes a shrill, pure, high-pitched breeding call. Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica): The first frog to emerge in the spring, the wood frog can tolerate cold and even freezing temperatures for short periods of ©USGS NEARMI time. It has a dark mask over and below each eye ©USGS NEARMI and is otherwise dark red or tan. Wood frogs are widespread in Maine but limit their breeding generally to temporary or vernal pools. The wood frog’s call sounds like the quack of a duck. ©James Hardy ©James Hardy American Toad (Bufo americanus): Maine’s only toad, the American toad has dry, bumpy skin and is largely terrestrial, going in water only to breed and lay eggs. Its call is a high, musical trill that can last 30 seconds or more. Northern Leopard Frog (Rana pipiens): Apparent declines in the population make the northern leopard frog a species of “Special Concern” in the state of Maine. The leopard frog and its close cousin the pickerel frog are the only frogs in Maine with distinct spots. The leopard frog has two to three unevenly spaced rows of irregular oval spots on its back. -

Exotic and Invasive Alien Species in Newfoundland and Labrador

EXOTIC SPECIES: For More Information: Exotic and Invasive Alien Species Plants, animals and micromicro----organismsorganisms in Newfoundland and Labrador existing in habitats beyond their natural distribution. Their introduction is Department of Environment and usually caused by humans or human Conservation activities but most do not become Wildlife Division Newfoundland and Labrador is home to tens of invasive. Exotic species are also referred to Endangered Species and Biodiversity thousands of animals, plants, and other organisms. as introduced, nonnon----native,native, alien and nonnon---- Phone: (709) 637-2026 Together, these species create the unique indigenous species. www.gov.nl.ca/ environment and diverse habitats of the province. INVASIVE ALIEN SPECIES: However, intentionally or accidentally, exotic Botanical Gardens of Memorial University species have been introduced to the province. Harmful exotic species whose Memorial University of Newfoundland and While most exotics may have little or no impact on introduction or spread threatens the Labrador Cabbage White, S. Pardy Moores local ecosystems, some species may become environment, economy, or society, Phone: (709) 737-8590 www.mun.ca/botgarden invasive. including human health. PATHWAYS OF INTRODUCTION: Exotic and Canadian Biodiversity Network The activity, most commonly human, www.cbin.ec.gc.ca that provides the opportunity for species to establish in new habitats. Wild Species 2005 Invasive Alien www.wildspecies.ca THREATS: IAS Concepts, Terms & Context, CAB The potential negative outcomes to a http://www.cabi.org/ias_ctc.asp?Heading=Terms Species in habitat or species after the introduction of an exotic species. Threats include IUCN 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species biodiversity loss, introduction of www.issg.org/database Newfoundland Snowshoe Hare Coltsfoot predators, and loss of food source. -

Chirp, Croak, and Snore

MINNESOTA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER Young Naturalists Teachers Guide Prepared by “Chirp, Croak, and Snore” Multidisciplinary Jack Judkins, Classroom Activities Curriculum Teachers guide for the Young Naturalists article “Chirp, Croak, and Snore” by Mary Hoff. Connections Published in the March–April 2014 Minnesota Conservation Volunteer, or visit www.dnr.state.mn.us/young_naturalists/frogs-and-toads-of-minnesota/index.html. Minnesota Young Naturalists teachers guides are provided free of charge to classroom teachers, parents, and students. This guide contains a brief summary of the article, suggested independent reading levels, word count, materials list, estimates of preparation and instructional time, academic standards applications, preview strategies and study questions overview, adaptations for special needs students, assessment options, extension activities, Web resources (including related Minnesota Conservation Volunteer articles), copy-ready study questions with answer key, and a copy-ready vocabulary sheet and vocabulary study cards. There is also a practice quiz (with answer key) in Minnesota Comprehensive Assessments format. Materials may be reproduced and/or modified to suit user needs. Users are encouraged to provide feedback through an online survey at www.mndnr.gov/education/teachers/activities/ynstudyguides/survey.html. *All Minnesota Conservation Volunteer articles published since 1940 are now online in searchable PDF format. Visit www.mndnr.gov/magazine and click on past issues. Summary “Chirp, Croak, and Snore” surveys -

Forest Hill FIELD GUIDE

Forest Hill FIELD GUIDE FOREST HILL ALMA COLLEGE GIRESD ii • Forest Hill History • Forest Hill Nature Area www.GratiotConservationDistrict.org Forest Hill Nature Area, located in northern Gratiot County, Michigan, is land that has been set aside for the preservation and appreciation of the natural world. The nature area has walking trails through 90 acres of gently rolling hills, open fields, wetlands, Let children walk with nature. Let them see the beautiful blendings willow thickets, and woodlots. Forest Hill Nature Area is home to a and communions of death and life. Their joys inseparable unity. As variety of wildlife such as white-tailed deer, muskrats, ducks and taught in woods and meadows. Plains and mountains. And turkeys. streams. -John Muir Also, over the years, some farm buildings were demolished while others were renovated. The Nature Area has evolved into an Forest Hill Nature Area: important outdoor educational resource for the school children in Gratiot and Isabella Counties as well as the citizens of Mid- In 1992, the Gratiot County Soil Conservation District acquired a Michigan. Since 1993, thousands of school children and adults 90 acre abandoned farm from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. have participated in field trips and nature programs at Forest Hill In 1993, the District leased the property to the Gratiot-Isabella Nature Area. RESD to develop an outdoor education center. The RESD named the property, the Forest Hill Nature Area and in partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began a major wetland restoration project. 3 Digital Nature Trail Forest Hill is brimming with biodiversity and all it entails: succession, evolution, adaptation, wildlife and food chains. -

Kermit the Frog

written and illustrated by Mrs. Shellenberger’s First Graders Stony Point School April 2006 We dedicate this book to Jerry Pallotta who wrote the greatest books, Mary Lou Lundgren who helped us with art, research and writing, and to all our friends and families. How We Did It! We were reading the Jerry Pallotta alphabet books, The Yucky Reptile Alphabet Book and The Icky Bug Alphabet Book and wondered about making our own alphabet class book. Maysn brought tadpoles for our class and Ms. Shellenberger thought frogs were really cool. We got books from the library and our own class library and brainstormed a list of all the frogs we could find. We never knew there were so many kinds of frogs. We found out a lot of information from the computer. Ms. Shellenberger made us a special research process log to write and draw in. We drew the red-eyed tree frog with MaryLou Lundgren and figured out all the frog parts. We painted frogs on the computer, too. First, we made the outline and then we colored them. We found a dead dried-up frog in the Japanese Garden. It was interesting to see it up close. We used a magnifying glass. We used the magnifying glass to look at the tadpoles, too, so we could sketch them. The tadpoles grew pretty slow. We took pictures of them for the class web page. After we checked out all the books, we decided which frog we wanted to study more. We drew them on the cover of our process log using colored pencils. -

The Frog Files (K-6) [PDF – 5.67

AN EDUCATOR’S GUIDE TO FROGS K-6 Author: Terra Brie Stewart Koval, [email protected] Design & Illustrations: Rost Koval, [email protected], www.mangobonz.150m.com Editor: Neala MacDonald Frogwatch Illustrations: Wallace Edwards, courtesy of the Toronto Zoo This guide has been written by Terra Brie Stewart Koval and designed by Rost Koval through a Science Horizon's Grant with additional support from the Ecological Monitoring and Assessment Network Coordinating Office. This teachers guide is free from copyright when used for educational purposes. If reproduced we ask that you credit the author and the Ecological Monitoring and Assessment Network Coordination Office. DEAR EDUCATOR, Throughout most of history, people have not regarded reptiles and amphibians with high opinion. In fact the 18th century Swedish botanist and zoologist Carolus Linnaeus, famous for his classification system, presented a very strong example of the prevailing attitude toward reptiles and amphibians: "These foul and loathsome animals are abhorrent because of their cold body, pale colour, cartilaginous skeleton, filthy skin, fierce aspect, calculating eye, offensive smell, harsh voice, squalid habitation, and terrible venom; and so their Creator has not exerted his powers to make more of them." Although this attitude may still be representative of many people’s impressions of snakes, it seems that for the most part, our attitude towards frogs has grown to be a little more civilized—or at least it remains so in our children. Children are fascinated by frogs—and with good reason. They are cute, they are easily caught, they make cool sounds, and they have been found in abundance (although their decline is the whole reason programs like FrogWatch have come into existence). -

Alternative Crossings: a Study on Reducing Highway 49 Wildlife

Alternative Crossings: A Study On Reducing Highway 49 Wildlife Mortalities Through The Horicon Marsh Prepared By: Bradley Wolf, Pa Houa Lee, Stephanie Marquardt, & Michelle Zignego Table of Contents Chapter 1: Horicon Marsh Background ........................................................................................................ 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 History of the Horicon Marsh and Highway 49 ......................................................................................... 2 Geography of the Horicon Marsh ............................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 2: Natural History of Target Species ............................................................................................... 6 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Literature Review ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Natural History of the Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) ............................................................................... 7 Natural History of the Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) ...................................................................... 9 Natural History of Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) ............................................................................... -

State Wildlife Grants in Action

Michigan’s Wildlife Action Plan State Wildlife Grants Funding in Action Project Summaries 2005-2010 The Michigan Department of Natural Resources provides equal opportunities for employment and access to Michigan's natural resources. Both State and Federal laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, disability, age, sex, height, weight or marital status under the U.S. Civil Rights Acts of 1964 as amended, 1976 MI PA 453, 1976 MI PA 220, Title V of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 as amended, and the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act, as amended. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility, or if you desire additional information, please write: Human Resources, Michigan Department of Natural Resources, PO Box 30473, Lansing MI 48909-7973, or Michigan Department of Civil Rights, Cadillac Place, 3054 West Grand Blvd, Suite 3-600, Detroit, MI 48202, or Division of Federal Assistance, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Mail Stop MBSP-4020, Arlington, VA 22203. For information or assistance on this publication, contact Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Division, P.O. Box 30444, MI 48909. This publication is available in alternative formats upon request. Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Habitat Management – Project -

Incorporating Climate Change Refugia Into Climate Adaptation in the Acadia National Park Region Jennifer Smetzer Smith College, [email protected]

Smith ScholarWorks Climate Change Refugia in the Acadia National Second Century Stewardship Refugia Products Park Region 2019 Incorporating Climate Change Refugia Into Climate Adaptation in the Acadia National Park Region Jennifer Smetzer Smith College, [email protected] Toni Lyn Morelli University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/second_century_refugia Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons Recommended Citation Smetzer, Jennifer and Morelli, Toni Lyn, "Incorporating Climate Change Refugia Into Climate Adaptation in the Acadia National Park Region" (2019). Article, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/second_century_refugia/44 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Second Century Stewardship Refugia Products by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] INCORPORATING CLIMATE CHANGE REFUGIA INTO CLIMATE ADAPTATION IN THE ACADIA NATIONAL PARK REGION Jennifer Smetzer 1, Toni Lyn Morelli 2 1. Smith College, Department of Statistical & Data Sciences 2. US Geological Survey, University of Massachusetts Amherst, & Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 3 2. Methods .................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 Initial Stakeholder Meeting -

Creating Frog Friendly Landscape Ponds

Creating Frog Friendly Landscape Ponds Frog Habitat - Wisconsin is home to 12 species of frogs, all of which require standing water for breeding. Some species, such as the wood frog, can begin breeding as early as March in a warm year while others, such as the Blanchard’s cricket frog, breed later in the summer. The green frog, American bullfrog, and mink frog typically (although not always) require large permanent waterbodies for breeding because their tadpoles take 1-2 years to develop; however the remaining 9 frog species in Wisconsin routinely utilize smaller waterbodies for breeding, such as landscape ponds. For additional information on Wisconsin’s frogs, please visit the Department of Natural Resources web site: dnr.wi.gov/topic/WildlifeHabitat/herps.asp?mode=table&group=Frogs. Pond Recommendations - If you are considering creating a landscape pond and would like to make it as frog friendly as possible, please follow the recommendations below. You will not need to add frogs to the pond once you have it completed, they will find new suitable habitat very quickly, often in as little as 1 year! With a smaller pond and fairly uniform habitat nearby, you can expect 1-4 species, however with a larger pond and a variety of habitats nearby, you could expect up to 6-8 species throughout the year. Different frog species call during various times of the year, so frogs in your pond may spread out their calling throughout the spring and summer. The size (surface area) of the pond is not extremely important (although typically the larger the better), however, irregular borders or curvature to the shape of the pond are beneficial and create a variety of microhabitats and areas of shelter. -

The Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas 2013 Update

The Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas Ring-necked Snake, photo by Kiley Briggs 2013 Update James S. Andrews with the help of over 5,000 volunteers and cooperating organizations Cartography by Kiley Briggs Funded by: the Lintilhac Foundation, the Norcross Wildlife Foundation, the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, and the Vermont Monitoring Cooperative. Table of Contents Copyright and Recommended Citation ............................................................................................................. 2. Introduction and History .................................................................................................................................... 3. Vermont Reptiles and Amphibians .................................................................................................................... 4. Relative Abundance Tables ................................................................................................................................. 6. Useful Sources of Information ............................................................................................................................ 8. Additional Reading ............................................................................................................................................ 10. Search Tips and Handling ................................................................................................................................. 13. Permits ...............................................................................................................................................................