High Speed Rail (London- West Midlands) Health Impact Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lea Marston to Tamworth

High Speed Two Phase 2b ww.hs2.org.uk October 2018 Working Draft Environmental Statement High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report | Volume 2 | LA01 LA01: Lea Marston to Tamworth High Speed Two (HS2) Limited Two Snowhill, Snow Hill Queensway, Birmingham B4 6GA Freephone: 08081 434 434 Minicom: 08081 456 472 Email: [email protected] H12 hs2.org.uk October 2018 High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report LA01: Lea Marston to Tamworth H12 hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, Two Snowhill Snow Hill Queensway Birmingham B4 6GA Telephone: 08081 434 434 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk A report prepared for High Speed Two (HS2) Limited: High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. © High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, 2018, except where otherwise stated. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. -

Nickey Line Greenspace Action Plan 2019 – 2024

NICKEY LINE GREENSPACE ACTION PLAN 2019 – 2024 Produced by: On behalf of: OVERVIEW Greenspace Action Plans Greenspace Actions Plans (GAPs) are map-based management plans which specify activities that should take place on a site over a stated period of time; these activities will help to deliver the agreed aspirations which the site managers and stakeholders have identified for that site. Public Engagement Engagement with stakeholders is at the centre of effective management planning on any site. An initial engagement period was held for five weeks in December 2017 and January 2018, to establish core aims and objectives for the site; these are reflected in Section 3. This plan has been produced for a second stage of engagement to enable stakeholders to comment on the proposed management actions for the site. Coordination with St Albans City & District Council As the Nickey Line leaves from Hemel Hempstead towards Redbourn, it crosses into the St Albans District Council (SADC) administrative area. A GAP is already in place for the St Albans section. The programme of works for the Dacorum section has been produced to complement the programme in the St Albans section. A coordinated approach will be taken wherever practical to deliver projects jointly to ensure continuity across the administrative boundary. Version Control Version Issue Date Details Author Reviewed Approved Original issue following DBC 01 April 2018 GA initial public engagement Officers November Updated following DBC DBC 02 GA 2018 review Officers Nickey Line (Dacorum) Greenspace Action Plan 2019-2024 i CONTENTS 1.0 Summary ................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Site Summary ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Vision Statement .................................................................................................... -

Quality As a Space to Spend Time Proximity and Quality of Alternatives Active Travel Networks Heritage Concluaiona Site No. Site

Quality as a space to spend Proximity and quality of Active travel networks Heritage Concluaiona time alternatives GI network (More than 1 of: Activities for different ages/interests Where do spaces currently good level of public use/value, Within such as suitability for informal sports and play/ provide key walking/cycling links? Biodiversity, cta, sports, Public Access Visual interest such as variety and colour Number of other facilities Which sites do or Agricultural Active Travel Networks curtilage/a Historic Local Landscape value variety of routes/ walking routes Level of anti-social behaviour (Public rights of way SSS Conservation Ancient OC Flood Zone In view allotments, significant visual Individual GI Site No. Site Name (Unrestricted, Description of planting, surface textures, mix of green Level of use within a certain distance that could best provide Land SAC LNR LWS (Directly adjacent or djoining In CA? park/garde Heritage Landscape Type of open space in Local Value Further Details/ Sensitivity to Change Summary Opportunities /presence, quality and usage of play and perceptions of safety National Cycle Network I Target Areas Woodlands WS (Worst) cone? interest or townscape protections Limited, Restricted) and blue assets, presence of public art perform the same function alternatives, if any Classification containing a network) listed n Assets this area equipment/ Important local connections importance, significant area of building? presence of interactive public art within Oxford) high flood risk (flood zone 3)) Below ground Above ground archaeology archaeology Areas of current and former farmland surrounded by major roads and edge of city developments, such as hotels, garages and Yes - contains two cycle Various areas of National Cycle Routes 5 and 51 Loss of vegetation to development and Northern Gateway a park and ride. -

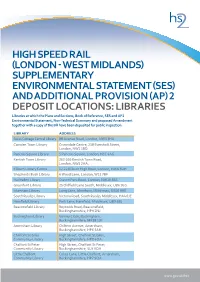

High Speed Rail

HIGH SPEED RAIL (LONDON - WEST MIDLANDS) SUPPLEMENTARY ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT (SES) AND ADDITIONAL PROVISION (AP) 2 DEPOSIT LOCATIONS: LIBRARIES Libraries at which the Plans and Sections, Book of Reference, SES and AP2 Environmental Statement, Non-Technical Summary and proposed Amendment together with a copy of the Bill have been deposited for public inspection. LIBRARY ADDRESS Swiss Cottage Central Library 88 Avenue Road, London, NW3 3HA Camden Town Library Crowndale Centre, 218 Eversholt Street, London, NW1 1BD Pancras Square Library 5 Pancras Square, London, N1C 4AG Kentish Town Library 262-266 Kentish Town Road, London, NW5 2AA, Kilburn Library Centre 12-22 Kilburn High Road, London, NW6 5UH Shepherds Bush Library 6 Wood Lane, London, W12 7BF Harlesden Library Craven Park Road, London, NW10 8SE Greenford Library 25 Oldfield Lane South, Middlesex, UB6 9LG Ickenham Library Long Lane, Ickenham, Middlesex, UB10 8RE South Ruislip Library Victoria Road, South Ruislip, Middlesex, HA4 0JE Harefield Library Park Lane, Harefield, Middlesex, UB9 6BJ Beaconsfield Library Reynolds Road, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, HP9 2NJ Buckingham Library Verney Close, Buckingham, Buckinghamshire, MK18 1JP Amersham Library Chiltern Avenue, Amersham, Buckinghamshire, HP6 5AH Chalfont St Giles High Street, Chalfont St Giles, Community Library Buckinghamshire, HP8 4QA Chalfont St Peter High Street, Chalfont St Peter, Community Library Buckinghamshire, SL9 9QA Little Chalfont Cokes Lane, Little Chalfont, Amersham, Community Library Buckinghamshire, HP7 9QA www.gov.uk/hs2 -

London- West Midlands ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Volume 2 | Community Forum Area Report CFA20 | Curdworth to Middleton

LONDON-WEST MIDLANDS ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT ENVIRONMENTAL MIDLANDS LONDON-WEST | Vol 2 Vol LONDON- | Community Forum Area report Area Forum Community WEST MIDLANDS ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Volume 2 | Community Forum Area report CFA20 | Curdworth to Middleton | CFA20 | Curdworth to Middleton to MiddletonCurdworth November 2013 VOL VOL VOL ES 3.2.1.20 2 2 2 London- WEST MIDLANDS ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Volume 2 | Community Forum Area report CFA20 | Curdworth to Middleton November 2013 ES 3.2.1.20 High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. A report prepared for High Speed Two (HS2) Limited: High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, Eland House, Bressenden Place, London SW1E 5DU Details of how to obtain further copies are available from HS2 Ltd. Telephone: 020 7944 4908 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. Printed in Great Britain on paper containing at least 75% recycled fibre. CFA Report – Curdworth to Middleton/No 20 | Contents Contents 1 Introduction -

Kilburn Priory Children's Centre Weekly Programme and Activity

Camden Sure Start Kilburn Priory: 020 7974 5080 6. Sidings Community Centre Children’s centre 150 Brassey Road, 1. Kilburn Grange Children’s Centre London NW6 2BA 4 Stay & Play drop-ins 020 7624 0588 FINCHLEY Early education and childcare W 7. The Sherriff Centre ES RD Employment & free benefits advice T E ND St James Church, Sherriff Road, L Family Support Team A London NW6 2AP N FINCHLEY Midwifery and Health Visiting services E 020 7625 1184 Y RD 1 Palmerston Road, London NW6 2JL D 8. Kingsgate Community Centre Hampstead FINCHLEY ROAD VE. 020 7974 5080 10 Cricket Club & FROGNAL A 107 Kingsgate Road, SHOOT London NW6 2JH Local authority nursery WEST HAMPSTEAD 020 7328 9480 -UP HILL 6 THAMESLINK FITZJOHN’S 2. Langtry Nursery 11–29 Langtry Road, London NW8 0AJ Libraries WEST 020 7624 0963 HAMPSTEAD Rhyme time sessions for FINCHLEY Childcare options ROAD children under 5 WEST KILBURN N HAMPSTEAD COLLEGE L F C R For information on childcare options IN E 1 D S 9. Kilburn Library CH C N 7 L E contact the Family Information Service 8 E E N T Y T 12–22 Kilburn High Road, S KILBURNKKI HIGH RD E R on 020 7974 1679. L W D London NW6 5UH BRONDESBURY Kilburn For information on free 2 year old places Grange Park SWISS 020 7974 4001 COTTAGE see; camden.gov.uk/twoyearolds W AVA E RD E S 10. West Hampstead Library T SOUTH E E HAMPSTEAD N Other stay and play Dennington Park Road, D R L HILILLG O A V RD drop-in venues London NW6 1AU N E RD A’LAIDE RD W’DEN LN E 020 7974 4001 ABBEY RD ABBEY 3. -

Solihull, Birmingham and Warwickshire (Part A)

PROPERTY CONSULTATION 2014 For the London-West Midlands HS2 route Map books – Volume 5 | Solihull, Birmingham and Warwickshire (part a) July 2014 CS139_p www.hs2.org.uk PROPERTY CONSULTATION 2014 For the London-West Midlands HS2 route Map books – Volume 5 | Solihull, Birmingham and Warwickshire (part a) July 2014 High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, Eland House, Bressenden Place, London SW1E 5DU Telephone: 020 7944 4908 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. © High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, 2014, except where otherwise stated. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. This information is licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.0. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/2 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. -

Cicerone-Catalogue.Pdf

SPRING/SUMMER CATALOGUE 2020 Cover: A steep climb to Marions Peak from Hiking the Overland Track by Warwick Sprawson Photo: ‘The veranda at New Pelion Hut – attractive habitat for shoes and socks’ also from Hiking the Overland Track by Warwick Sprawson 2 | BookSource orders: tel 0845 370 0067 [email protected] Welcome to CICERONE Nearly 400 practical and inspirational guidebooks for hikers, mountaineers, climbers, runners and cyclists Contents The essence of Cicerone ..................4 Austria .................................38 Cicerone guides – unique and special ......5 Eastern Europe ..........................38 Series overview ........................ 6-9 France, Belgium, Luxembourg ............39 Spotlight on new titles Spring 2020 . .10–21 Germany ...............................41 New title summary January – June 2020 . .21 Ireland .................................41 Italy ....................................42 Mediterranean ..........................43 Book listing New Zealand and Australia ...............44 North America ..........................44 British Isles Challenges, South America ..........................44 Collections and Activities ................22 Scandinavia, Iceland and Greenland .......44 Scotland ................................23 Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, Albania ....45 Northern England Trails ..................26 Spain and Portugal ......................45 North East England, Yorkshire Dales Switzerland .............................48 and Pennines ...........................27 Japan, Asia -

Between Autumn 2011 and Spring 2012 Vale of White Horse District

SOUTH OXFORDSHIRE DISTRICT SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL REPORT OF THE SOUTH OXFORDSHIRE LOCAL PLAN PREFERRED OPTIONS 2 STAGE FOUR OF THE PROCESS MARCH 2017 South Oxfordshire District Council 135 Eastern Avenue Milton Park Milton OX14 4SB [email protected] www.southoxon.gov.uk/newlocalplan 01235 422600 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................. 2 The Local Plan 2033: What have we done so far................................................... 10 The Second Preferred Options Document ............................................................. 11 What does the Preferred Options document do? ................................................... 11 Sustainability Appraisal Consultation ..................................................................... 12 SEA Directive ......................................................................................................... 12 Sustainability Appraisal Methodology .................................................................... 17 Stage B: Developing and refining alternatives and assessing effects ............ 31 Vision and Objectives ............................................................................................ 32 Our Vision for 2033 ................................................................................................ 32 Sustainability Appraisal of the Local Plan Strategic Objectives ............................. 34 Local Plan Distribution Strategy ............................................................................ -

Performance Changes Caused by Increases in Camden Libraries’ Opening Hours

PERFORMANCE CHANGES CAUSED BY INCREASES IN CAMDEN LIBRARIES’ OPENING HOURS In January 2009, Camden Council increased the opening hours of its public libraries. However, it did not increase the opening hours by a constant number or a constant proportion, but by a method which favoured bigger libraries. CPLUG had argued strenuously against this, but to no avail. CPLUG’s Concerns The suggested reason for increasing Camden’s library opening hours was that it would enable more people to visit the libraries. CPLUG did not disagree with this assumption and attempted to ensure that the available resources were allocated where they would do the most good, rather than where was most bureaucratically convenient. This “value for money” argument went unheeded. One of CPLUG’s major concerns was the effect that a large allocation of resources to the Swiss Cottage Library (library no. 3 in map below) would have on the surrounding smaller libraries. In the recent past, this library has benefited when other libraries have not. Thus, the public increasingly has tended to use Swiss Cottage in place of the local libraries. It is to be expected that this cannibalisation of the user pool will lead to a continually reinforced downward spiral for the small libraries and is a recipe for eventual library closures - very bad news for those who have difficulty travelling. It is also bad for community cohesion and for the environment. It is tempting to assume that the cost of implementing the opening hours changes is simply proportional to the change in those hours. However, the size of the library has a marked affect on the cost. -

C) of the GAS ACT 1986 of the GRANT of a GAS SUPPLY LICENCE Pursuant to Section 7B(9

NOTICE UNDER SECTION 7B(9)(c) OF THE GAS ACT 1986 OF THE GRANT OF A GAS SUPPLY LICENCE Pursuant to section 7B(9)(c) of the Gas Act 1986 ("the Act"), the Gas and Electricity Markets Authority ("the Authority") hereby gives notice that on 18 January 2007 a gas supply licence was granted under section 7A(l)(a) of the Act to London Borough of Camden whose principal office is situated at Town Hall, Judd Street, London, WClH 9LP, Great Britain, authorising the supply to premises specified in Appendix 1, gas which has been conveyed through pipes to those premises. A copy of this licence is available from the Ofgem Library, 9 Millbank, London, SWIP 3GE (020 7901 7003) or by email at [email protected]. 18 January 2007 of the Authority Appendix 1 Site Site address Meter serial number Aldenharn House Aldenharn Street. NW1 1PR HI71156 Arnpthill Square Estate Arnpthill Square NW1 G9877 Bucklebury Stanhope Street NW1 3LB 8009970 Carnden High Street 80 Flat 80 Camden High Street NWl OLT 3663931 Carnden High Street 80 80 Flat 1 Carnden High Street NW1 OLT 260439 Camden High Street 80 80 Flat 3 Carnden High Street NW1 OLT 3706997 Carnden Road No.79 79 Carnden Road NW1 SEX CD34807 Cecil Rhodes House Goldington Street NW1 1UG 901 152 Churchway House Churchway NW1 CD35186 Clarendon House Werrington Street NW1 1PL Cd32707 Clarendon House Werrington Street NW1 1PL CD32620 Cobden House Arlington Road NW1 7LL CD32762 Cobden House Arlington Road NW1 7LL 8005486 College Place Estate Plender Street NW1 34449353 College Place Estate Plender Street NW1 8000894 -

Nickey Line Greenspace Action Plan, 2021 - 2026

NICKEY LINE GREENSPACE ACTION PLAN, 2021 - 2026 BRIEFING DOCUMENT Produced by: On behalf of: CONTENTS 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 2. Background .................................................................................................................. 3 3. Review of Progress ...................................................................................................... 6 4. Greenspace Action Plan (GAP) 2018-2023 ................................................................. 7 5. Community Engagement and Plan Production Process ........................................... 9 6. Stakeholder Feedback ............................................................................................... 11 Nickey Line Greenspace Action Plan 2021-2026 Briefing Document 1 1. INTRODUCTION A new five year Greenspace Action Plan (GAP) is being produced for the section of the Nickey Line within St Albans district. This briefing document provides an overview of how the GAP will be produced and sets out how stakeholders can contribute to shaping the plan. GAPs are essentially map-based management plans that provide focus and direction for the running and improvement of open spaces. They provide a clear, logical process to determine the activities that should take place over a stated period of time to achieve the objectives for the site. The GAP is being produced by the Countryside Management Service (CMS), part of Hertfordshire County Council’s