Bad Seeds and Holy Terrors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theatre Review: 'Ruthless! the Musical' at Heritage Players

Home About Us Write for Us Auditions and Opportunities Advertising Contact Us ! " # $ Theatre Guide What’s Playing Half-Price Tickets Reviews Columns News * ! ! ! ! ! ! LATEST POSTSTheatre News: Announcement of Awards of 20th Annual Washington Area Theatre Community Honors (WATCH) ) Theatre News:2:49:48 2020 ‘Contemporary American Theater Festival’ Canceled WHAT’S PLAYING Theatre Review: ‘Ruthless! The Musical’ at Heritage Players Posted By: Timoth David Copney on: October 30, 2019 % Print ' Email SUBSCRIBE TO NEWSLETTER Weekly email with links to latest posts. (Be sure to answer confirmation email.) Name Name Brooke Webster as Tina. Email “Ruthless! The Musical” (exclamation mark included) is one of the quirkiest pieces of musical Email theatre to come down the pike in a long while and I am flat-out delighted it’s parked at Heritage Players in Catonsville. Submit Heritage Players is not known for presenting outré productions, but if this is a new directional trend then I am all for it. This weird mishmash of The Bad Seed, Gypsy, All About Eve, A Chorus Line and every bad mother/daughter/sociopathic killer movie is so tragically flawed as a story that it takes a while to realize that it has its tongue so firmly in its own cheek that it can’t possibly be meant to be taken seriously. And that’s what makes it so much fun. With a book and lyrics by Joel Paley and music by Marvin Laird, the musical made its Off- Broadway debut in 1992. It’s the ridiculous story of Judy Denmark, a Stepford-wife homemaker and her darling psychopath of a daughter, Tina. -

Till Death Do Us Part: a Study of Spouse Murder GEORGE W

Till Death Do Us Part: A Study of Spouse Murder GEORGE W. BARNARD, MD HERNAN VERA, PHD MARIA I. VERA, MSW GUSTAVE NEWMAN, MD Killers of members of their own families have long fueled the archetypical imagination. Our myths, literature, and popular arts are full of such charac ters as Cain, Oedipus, Medea, Othello, Hamlet, and Bluebeard. In our time the murderous children of movies like "The Bad Seed" and "The Omen"; the homicidal father of "The Shining"; the killer spouses of Hitchcock's "Midnight Lace" and "The Postman Always Rings Twice" bespeak a continuing fascination with the topic. In contrast, until recently the human sciences paid" selective inattention" I to the topic of family violence. Only in the past decade has violence in the family become "a high priority social issue,"~ an "urgent situation, ":1 on which privileged research energy needs to be expended. We deal here with the murder of one spouse by the other, a topic on which research remains sparse4 despite the growing interest in family vio lence. Based on data derived from twenty-three males and eleven females accused of such crime, we contrast and compare the two groups attempting to identify common and gender-related characteristics in the offense, the relationship between murderer and victim, as well as the judicial disposition of the accused. The importance of the doer-sufferer relation in acts of family criminal violence has been well established. In major sociological studies"-s it has been found that about one out of five (or nearly one out of four) deaths by murder in the U.S. -

OBSCENE, INDECENT, IMMORAL, and OFFENSIVE 100+ Years Of

ch00_5212.qxd 11/24/08 10:17 AM Page iii OBSCENE, INDECENT, IMMORAL, AND OFFENSIVE 100+ Years of Censored, Banned, and Controversial Films STEPHEN TROPIANO ELIG IM HT L E DITIONS LIMELIGHT EDITIONS An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation New York ch00_5212.qxd 11/24/08 10:17 AM Page iv Copyright © 2009 by Stephen Tropiano All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, without written permission, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review. Published in 2009 by Limelight Editions An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation 7777 West Bluemound Road Milwaukee, WI 53213 Trade Book Division Editorial Offices 19 West 21st Street, New York, NY 10010 Printed in the United States of America Book design by Publishers’ Design and Production Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request. ISBN: 978-0-87910-359-0 www.limelighteditions.com ch04_5212.qxd 11/21/08 9:19 AM Page 143 CHAPTER 4 Guns, Gangs, and Random Acts of Ultra-Violence n the silent era, the cinematic treatment of crime and criminals was a major point of contention for those who believed there was a Idirect cause-and-effect link between the depiction of murder, rape, and violence and real crimes committed by real people in the real world. They were particularly concerned about the negative effects of screen violence on impressionable youth, who were supposedly prone to imitate the bad behavior they might witness in a dark movie theatre one sunny Saturday afternoon. -

Rethinking the Intersection of Cinema, Genre, and Youth James Hay, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA

Rethinking the Intersection of Cinema, Genre, and Youth James Hay, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA The "Teen Film," Genre Theory, and the Moral Universe ofPlanetariums In most accounts of the "teen film," particularly those accounts tracing its origins, films such as Blackboard Jungle (1955) and Rebel Without a Cause (1956) have served as crucial references, not only for assembling and defining a corpus of films as a genre but also for describing the genre's relation to a socio-historical formation/context. I begin this essay not with an elaborate reading of these films, nor with a deep commitment to reading films or charting homologies between them, nor with an abiding interest in defining teen films (though I do want to discuss how teen films and film genres have been defined), nor with a sense that these are adequate ways of understanding the relation of cinema or youth to social and cultural formation. There are in fact many good reasons to begin from other starting points than these films in order to discuss the relation of youth and cinema during the 1950s or thereafter. Because these films regularly have figured into accounts of the teen film, however, two particular scenes in these films offer a useful way to think about the objectives of film genre theory and criticism, particularly as they have informed accounts of the teen film, and to suggest an alternative way of thinking about genre, youth, and cinema. Both of these scenes occur at sites where the films' young characters become the subjects of screenings conducted by adult figures who explain to the students the significance of what they are viewing. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

There Is an Iconic Scene in the 1955 Film the Blackboard Jungle

UC Santa Barbara Journal of Transnational American Studies Title A Transnational Tale of Teenage Terror: The Blackboard Jungle in Global Perspective Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2bf4k8zq Journal Journal of Transnational American Studies, 6(1) Author Golub, Adam Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.5070/T861025868 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California A Transnational Tale of Teenage Terror: The Blackboard Jungle in Global Perspective by Adam Golub The Blackboard Jungle remains one of Hollywood’s most iconic depictions of deviant American youth. Based on the bestselling novel by Evan Hunter, the 1955 film shocked and thrilled audiences with its story of a novice teacher and his class of juvenile delinquents in an urban vocational school. Among scholars, the motion picture has been much studied as a cultural artifact of the postwar era that opens a window onto the nation’s juvenile delinquency panic, burgeoning youth culture, and education crisis.1 What is less present in our scholarly discussion and teaching of The Blackboard Jungle is the way in which its cultural meaning was transnationally mediated in the 1950s. In the midst of the Cold War, contemporaries viewed The Blackboard Jungle not just as a sensational teenpic, but as a dangerous portrayal of U.S. public schooling and youth that, if exported, could greatly damage America’s reputation abroad. When the film did arrive in theaters across the globe, foreign critics often read this celluloid image of delinquent youth into broader -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Blackboard Bodhisattvas

! ! BLACKBOARD BODHISATTVAS: ! NARRATIVES OF NEW YORK CITY TEACHING FELLOWS ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A DISSERTATION ! SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION ! AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES ! OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY ! IN PARTIAL REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF ! DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Brian D. Edgar June, !2014 © 2014 by Brian Douglas Edgar. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/kw411by1694 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. John Willinsky, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Labaree, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ari Kelman I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Raymond McDermott Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost for Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. -

When Victims Become Perpetrators

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2005 The "Monster" in All of Us: When Victims Become Perpetrators Abbe Smith Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/219 38 Suffolk U. L. Rev. 367-394 (2005) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons GEORGETOWN LAW Faculty Publications February 2010 The "Monster" in All of Us: When Victims Become Perpetrators 38 Suffolk U. L. Rev. 367-394 (2005) Abbe Smith Professor of Law Georgetown University Law Center [email protected] This paper can be downloaded without charge from: Scholarly Commons: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/219/ Posted with permission of the author The "Monster" in all of Us: When Victims Become Perpetrators Abbe Smitht Copyright © 2005 Abbe Smith I and the public know What all school children learn, Those to whom evil is done Do evil in return. 1 I. INTRODUCTION At the end of Katherine Hepburn's closing argument on behalf of a woman charged with trying to kill her philandering husband in the 1949 film Adam's Rib,2 Hepburn tells the jury about an ancient South American civilization in which the men, "made weak and puny by years of subservience," are ruled by women. She offers this anthropological anecdote in order to move the jury to understand why a woman, whose "natural" feminine constitution should render her incapable of murder,3 might tum to violence. -

Or a Bad Seed?

Good vs. Bad Everyone has good moments, like cheering up a sad friend, but they also have bad moments too, like fighting with a sibling. Draw a picture of yourself being a Good Egg in the left column and a picture of yourself being a Bad Seed in the right column. GOOD BAD www.harpercollinschildrens.com Art copyright © 2019 Pete Oswald. Permission to reproduce and distribute this page has been granted by the copyright holder, HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved. A Helping Hand The bad seed says he wasn’t always a bad seed. How do you think he felt when he heard others call him a “bad seed”? How could the others have helped him instead? Draw a picture of what you would have done to help the bad seed. www.harpercollinschildrens.com Art copyright © 2019 Pete Oswald. Permission to reproduce and distribute this page has been granted by the copyright holder, HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved. Five Ways to Be a Good Egg At the beginning of the story, the Good Egg shows how good he is by helping carry groceries, getting a cat down from a tree, and even painting a house. In the boxes below, draw five ways you can be a good egg too! www.harpercollinschildrens.com Art copyright © 2019 Pete Oswald. Permission to reproduce and distribute this page has been granted by the copyright holder, HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved. Eggs to Crack You Up Along with the Good Egg, the other eggs make a great bunch. All of them are silly and funny in their own ways, and they have the best faces. -

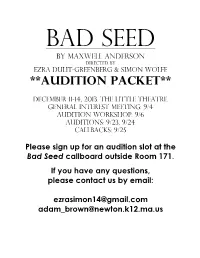

Audition Packet**

Bad Seed By Maxwell Anderson Directed by Ezra Dulit-Greenberg & Simon wolfe **Audition packet** DECEMBER 11-14, 2013. The Little Theatre. General Interest Meeting: 9/4 Audition Workshop: 9/6 Auditions: 9/23, 9/24 Callbacks: 9/25 Please sign up for an audition slot at the Bad Seed callboard outside Room 171. If you have any questions, please contact us by email: [email protected] [email protected] Information Please sign up for one audition slot on the callboard outside Room 171 and pick up a script. You are required to read Bad Seed prior to your audition. Please fill out this packet and give it to a stage manager at your audition. Please prepare and memorize one of the monologues of your gender in this packet, and do the same for an additional monologue that is not from Bad Seed. Please have the second monologue you choose contrast with your choice from the packet. This means that it should highlight different emotions, intentions, and styles that show your acting range. In other words: if one monologue is dramatic, the other should be comedic. You will be asked to present both monologues. If you need any help finding a monologue, please ask or email Mr. Brown or us for help – we will be glad to provide it. If you would like to work on your audition, feel free to contact Mr. Brown or another student director. [email protected], [email protected] We are looking for actors with strong fundamentals (vocal energy, movement with purpose, etc.), honesty, and intention. -

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for Your Wife

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for your Wife by Ray Cooney presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French 9 to 5, The Musical by Dolly Parton presented by special arrangement with MTI Elf by Thomas Meehan & Bob Martin presented by special arrangement with MTI 4 Weddings and an Elvis by Nancy Frick presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French The Cemetery Club by Ivan Menchell presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Young Frankenstein by Mel Brooks presented by special arrangement with MTI An Inspector Calls by JB Priestley presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Newsies by Harvey Fierstein presented by special arrangement with MTI _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2019-2020 Season A Comedy of Tenors – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Mamma Mia – presented by special arrangement with MTI The Game’s Afoot – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French The Marvelous Wonderettes – by Roger Bean presented by special arrangement with StageRights, Inc. Noises Off – by Michael Frayn presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Cabaret – by Joe Masteroff presented by special arrangement with Tams-Witmark Barefoot in the Park – by Neil Simon presented by special arrangement with Samuel French (cancelled due to COVID 19) West Side Story – by Jerome Robbins presented by special arrangement with MTI (cancelled due to COVID 19) 2018-2019 Season The Man Who Came To Dinner – by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Mary Poppins - Original Music and Lyrics by Richard M.