Citizenship Studies the Work of Time in Western Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papers of Beatrice Mary Blackwood (1889–1975) Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

PAPERS OF BEATRICE MARY BLACKWOOD (1889–1975) PITT RIVERS MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Compiled by B. Asbury and M. Peckett, 2013-15 Box 1 Correspondence A-D Envelope A (Box 1) 1. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 20 May 1955. Summary: Acknowledging receipt of the Pitt Rivers Report for 1954. “The Museum as an institution seems beset with more difficulties than any other.” Giving details of the developing organisation of the Vancouver Museum and its index card system. Asking for a copy of Mr Bradford’s BBC talk on the “Lost Continent of Atlantis”. Notification that Mr Menzies’ health has meant he cannot return to work at the Museum. 2pp. 2. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 20 July 1955. Summary: Thanks for the “Lost Continent of Atlantis” information. The two Museums have similar indexing problems. Excavations have been resumed at the Great Fraser Midden at Marpole under Dr Borden, who has dated the site to 50 AD using Carbon-14 samples. 2pp. 3. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 12 June 1957. Summary: Acknowledging the Pitt Rivers Museum Annual Report. News of Mr Menzies and his health. The Vancouver Museum is expanding into enlarged premises. “Until now, the City Museum has truly been a cultural orphan.” 1pp. 4. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 16 June 1959. Summary: Acknowledging the Pitt Rivers Museum Annual Report. News of Vancouver Museum developments. -

Journal of Eastern African Studies Rethinking the State in Idi Amin's Uganda: the Politics of Exhortation

This article was downloaded by: [Cambridge University Library] On: 20 July 2015, At: 20:55 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Journal of Eastern African Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjea20 Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation Derek R. Peterson a & Edgar C. Taylor a a Department of History , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , MI , 48109 , USA Published online: 26 Feb 2013. To cite this article: Derek R. Peterson & Edgar C. Taylor (2013) Rethinking the state in Idi Amin's Uganda: the politics of exhortation, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 7:1, 58-82, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2012.755314 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda

DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 ISSN 2294-8651 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo Kristof Titeca Comments on this Discussion Paper are invited. Please contact the authors at: [email protected] and [email protected] While the Discussion Papers are peer- reviewed, they do not constitute publication and do not limit publication elsewhere. Copyright remains with the authors. Instituut voor Ontwikkelingsbeleid en -Beheer Institute of Development Policy and Management Institut de Politique et de Gestion du Développement Instituto de Política y Gestión del Desarrollo Postal address: Visiting address: Prinsstraat 13 Lange Sint-Annastraat 7 B-2000 Antwerpen B-2000 Antwerpen Belgium Belgium Tel: +32 (0)3 265 57 70 Fax: +32 (0)3 265 57 71 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.uantwerp.be/iob DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo* Kristof Titeca** March 2016 * Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University. ** Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB), University of Antwerp. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. ORIGINS OF THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 6 3. THE WALK-OUT FROM THE TORO RUKURATO AND THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 8 4. CONTINUATION OF THE RWENZURURU STRUGGLE 10 4.1. THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT AND ARMED STRUGGLE AFTER 1982 10 4.2. THE OBR AND THE MUSEVENI REGIME 11 4.2.1. THE RWENZURURU VETERANS ASSOCIATION 13 4.2.2. THE OBR RECOGNITION COMMITTEE 14 4.3. THE OBUSINGA AND THE LOCAL POLITICAL STRUGGLE IN KASESE DISTRICT. -

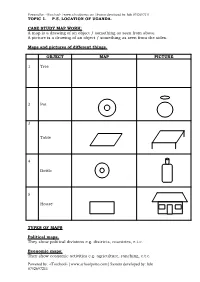

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

Environmental Decentralization and the Management of Forest Resources in Masindi District, Uganda

ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE IN AFRICA WORKING PAPERS: WP #8 COMMERCE, KINGS AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN UGANDA: DECENTRALIZING NATURAL RESOURCES TO CONSOLIDATE THE CENTRAL STATE by Frank Emmanuel Muhereza Febuary 2003 EDITORS World Resources Institute Jesse C. Ribot and Jeremy Lind 10 G Street, NE COPY EDITOR Washington DC 20002 Florence Daviet www.wri.org ABSTRACT This study critically explores the decentralizing of forest management powers in Uganda in order to determine the extent to which significant discretionary powers have shifted to popularly elected and downwardly accountable local governments. Effective political or democratic decentralization depends on the transfer of local discretionary powers. However, in common with other states in Africa undergoing various types of “decentralization” reforms, state interests are of supreme importance in understanding forest-management reforms. The analysis centers on the transfer of powers to manage forests in Masindi District, an area rich in natural wealth located in western Uganda. The decentralization reforms in Masindi returns forests to unelected traditional authorities, as well as privatizes limited powers to manage forest resources to licensed user-groups. However, the Forest Department was interested in transferring only those powers that increased Forest Department revenues while reducing expenditures. Only limited powers to manage forests were transferred to democratically elected and downwardly accountable local governments. Actors in local government were left in an uncertain and weak bargaining position following the transfer of powers. While privatization resulted in higher Forest Department revenues, the tradeoff was greater involvement of private sector actors in the Department’s decision making. To the dismay of the Forest Department, in the process of consolidating their new powers, private-sector user groups were able to influence decision making up to the highest levels of the forestry sector. -

State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 2

CONTENTS State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 2 1.0 Introduction 3 2.0 Methodology 5 3.0 Country Context 6 3.1 Political Economy 6 3.2 Political Enviroment 6 3.3 ICT Status 7 3.4 State Co-ownership of Network Operators and Infrastructure 8 3.5 Legal Protection of Human Rights 9 3.6 Status of ICT Legislation 11 4.0 Overview of Information Controls in Place 13 4.1 Content Controls in Legislation 13 4.1.1 Offensive Communication 14 4.1.2 Pornographic or Obscene Content 15 4.1.3 Hate Speech 16 4.1.4 Defamation 17 4.1.5 False Information “Fake news” 18 4.1.6 National Security and Terrorism 19 4.1.7 Censorship 20 4.1.8 Internet Shutdowns 21 4.1.8 Other Restrictions 22 5.0 Internet Intermediaries and Internet Freedom 23 5.1 Limitation of Liability on Intermediaries 23 5.2 Imposition of Liability on Intermediaries 24 5.3 Restrictions Imposed by Intermediaries 26 5.4 Violation of Privacy Rights 28 5.4.1 Processing and Disclosure of Personal Information 28 5.4.2 Retention of Content Data 29 5.4.3 Surveillance and Interception of Communication 30 5.4.4 Poor Accountability of Intermediaries 32 5.5 Inadequate Complaint Handling Frameworks and Remedies 33 5.6 Pushbacks Against Violations and the Promotion of Rights 34 6.0 Conclusion and Recommendations 36 6.1 Conclusion 36 6.2 Recommendations 37 6.2.1 Government 37 6.2.2 Intermediaries 38 6.3.3 Media 38 6.3.4 Academia 38 6.3.5 Technical Community 39 6.3.6 Civil Society 39 6.3.7 Public 39 3 State of Internet Freedom in Africa 2017 1.0 Introduction Growing use of the internet and related technologies has provided new spaces for advancing the right to freedom of expression (FOE), promoted access to information, and spurred innovation and socio-economic growth in various African countries. -

Uganda: Conflict Assessment Report for the Month of January 2017

UGANDA: CONFLICT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF JANUARY 2017 Issue Date: 6th February 2017 Disclaimer This publication was produced for review by the United State Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity & Peace (SAFE) Program. The author’s views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. National Overview Tension continues to rise in the Rwenzori sub region following the re-arrest of the King (Omusinga) Charles Wesley Mumbere of the Rwenzururu Kingdom (Obusinga Bwa Rwenzururu). He had been arrested in December 2016 on charges related to terrorism, aggravated robbery and attempted murder.1 These charges stemmed from attacks on police officers and police installations in the region in the last couple of months. King Mumbere was re-arrested just hours after Jinja High Court released him on bail. Prior to the re- arrest, one of the bail conditions was that he should not go to his Kingdom. The re-arrest of the King has not gone down well with some sections of his Kingdom. Area Members of the Parliament have condemned the re-arrest saying it was betrayal of the entire kingdom by the President of Uganda, and that the re-arrest was unlawful.2 However Police say King Mumbere was re-arrested because the latest investigations discovered other charges which he individually committed during the clashes in the region.3 The re-arrest of the King has the possibility of worsening the already precarious situation. In the last three years, more than three hundred (300) people have been killed, military installations attacked, houses, property and domestic livestock destroyed and many people injured in a conflict that is multidimensional. -

Roger Scott's

ROGER SCOTT'S m'jzi "MiWITi THE DEVELOPMENT OF TRADE UNIONS IN UGANDA ROGER SCOTT The history of the labour movement in East Africa has been unjustly neglected. This book is the first full- length study in this field. Roger Scott has brilliantly analysed the complex development of Uganda's Trade Union structure and its relationship with the political drive for independence. Shs. 27/50 IN EAST AFRICA an eaph publication for THE EAST AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL RESEARCH OTHER EAISR PUBLICATIONS AVAILABLE DEVELOPMENT PLANNING IN EAST AFRICA BY PAUL CLARK 16/- THE COMMON MARKET AND DEVELOPMENT IN EAST AFRICA BY PHILIP NDEGWA 15/- THE SUGAR INDUSTRY IN EAST AFRICA BY CHARLES FRANK 15/- TAXATION FOR DEVELOPMENT BY DHARAM GHAI 20/- (F\ write for our list: • EAST AFRICAN PUBLISHING HOUSE • KOINANGE STREET, P.O. BOX 30571, NAIROBI Is /O - iz The Development of Trade Unions in Uganda The Development of Trade Unions in Uganda by ROGER SCOTT East African Publishing House EAST AFRICAN PUBLISHING HOUSE Uniafric House, Koinange Street P.O. Box 30571, Nairobi First published 1966 Copyright © East African Institute of Social Research, Kampala, 1966 Made and printed in Kenya by Kenya Litho Ltd., Cardiff Road, Nairobi PREFACE This book is a product of three years' research as Rockefeller Foundation Teaching Fellow of the East African Institute of Social Research in Kampala. Field work, in the sense of exclusive con- centration on primary research, was conducted in two sections: a four months' visit immediately preceding Uganda's independence in October 1962 and the twelve months from July 1963. The material used in the case studies of individual unions was prepared at the beginning of 1964 although an attempt has been made to take account of subsequent changes by revision at the editorial stage. -

Collapse, War and Reconstruction in Uganda

Working Paper No. 27 - Development as State-Making - COLLAPSE, WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION IN UGANDA AN ANALYTICAL NARRATIVE ON STATE-MAKING Frederick Golooba-Mutebi Makerere Institute of Social Research Makerere University January 2008 Copyright © F. Golooba-Mutebi 2008 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) 1 Crisis States Research Centre Collapse, war and reconstruction in Uganda An analytical narrative on state-making Frederick Golooba-Mutebi∗ Makerere Institute of Social Research Abstract Since independence from British colonial rule, Uganda has had a turbulent political history characterised by putsches, dictatorship, contested electoral outcomes, civil wars and a military invasion. There were eight changes of government within a period of twenty-four years (from 1962-1986), five of which were violent and unconstitutional. This paper identifies factors that account for these recurrent episodes of political violence and state collapse. -

A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884

Peripheral Identities in an African State: A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884 Aidan Stonehouse Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Ph.D The University of Leeds School of History September 2012 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Shane Doyle whose guidance and support have been integral to the completion of this project. I am extremely grateful for his invaluable insight and the hours spent reading and discussing the thesis. I am also indebted to Will Gould and many other members of the School of History who have ably assisted me throughout my time at the University of Leeds. Finally, I wish to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for the funding which enabled this research. I have also benefitted from the knowledge and assistance of a number of scholars. At Leeds, Nick Grant, and particularly Vincent Hiribarren whose enthusiasm and abilities with a map have enriched the text. In the wider Africanist community Christopher Prior, Rhiannon Stephens, and especially Kristopher Cote and Jon Earle have supported and encouraged me throughout the project. Kris and Jon, as well as Kisaka Robinson, Sebastian Albus, and Jens Diedrich also made Kampala an exciting and enjoyable place to be. -

Uganda: Conflict Assessment Report for the Month of July 2014

UGANDA: CONFLICT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF JULY 2014 Issue Date: August 5, 2014 Disclaimer This publication was produced for review by the United State Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity & Peace (SAFE) Program. The author’s views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. INTRODUCTION The following is a Monthly Conflict Assessment Report provided by the USAID Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity and Peace (SAFE) Program for July 2014. The SAFE Program conducts monthly conflict assessments to better understand and respond to conflict patterns and trends as they develop throughout Uganda. Information is primarily filtered through SAFE’s trained Conflict Monitors who report on conflict incidents that occur in their communities. SAFE has Conflict Monitors based in West Nile, Acholi, Bunyoro and Karamoja sub regions, Gulu. The information provided by the Conflict Monitors is supplemented with reports issued by the media and civil society organizations (CSOs). The SAFE Program verifies reported incidents for accuracy. For a more detailed description of the monthly conflict assessment methodology, please refer to Appendix A. Seven Categories of conflicts are monitored in the Monthly Conflict Assessment: Land-related conflict Politically-motivated conflict Socio-ethnic conflict Ethnic conflict Conflict motivated by socio-economic issues or poverty Spill over and on-going conflicts that have expanded into new districts/countries Other conflicts that do not fall into the first six categories (see Annex B for the types of conflicts) The conflicts are additionally disaggregated by industry or sector, where relevant (for example, oil and gas, mining, infrastructure, manufacturing, and agriculture). -

The Tutsi and the Ha: a Study

The Tutsi and the Ha: A Study in Integration JAMES L. BRAIN State University of New York, New Paltz, New York, U.S.A. THE PAST decade has been the witness of bloody conflict between the former ruling elite of the Tutsi and the agricultural Hutu in the countries of Rwanda and Burundi. While it is true that Rwanda probably represented the stratified caste structure in its most extreme form, a very similar form of social structure did exist in the neighboring area of Buha in what is now Tanzania, and to date no comparable conflict and bloodshed has occurred. It is the pur- pose of this essay to examine why this was so. Although the colonial powers in their wisdom excised Rwanda and Burundi from formerly German Tangan- yika after the First World War, and gave them to Belgium, this did not, of course, alter the ethnic and cultural makeup of the area. Thus Buha, which under German administration had been separated from the Belgian Congo by Ruanda-Urundi, now found that it formed the frontier of British Tanganyika, and joined Belgian territory. In reality this did little to hinder local trade and movement between the areas, in spite of the police and customs posts set up on the main roads. Census figures (see Appendix) show that almost half the popu- lation of Kibondo District in Buha was composed of people classified as Rundi, and in the late 1950s efforts of local agricultural extension officers to improve the quality of tobacco offered for sale to B.A.T. Ltd (British American Tobacco Company Ltd) were nullified by the discovery that it was far more lucrative to sell any tobacco of any type across the border in Burundi than to grade and select leaf for sale through legitimate channels.