Jumping Into C++

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preview Objective-C Tutorial (PDF Version)

Objective-C Objective-C About the Tutorial Objective-C is a general-purpose, object-oriented programming language that adds Smalltalk-style messaging to the C programming language. This is the main programming language used by Apple for the OS X and iOS operating systems and their respective APIs, Cocoa and Cocoa Touch. This reference will take you through simple and practical approach while learning Objective-C Programming language. Audience This reference has been prepared for the beginners to help them understand basic to advanced concepts related to Objective-C Programming languages. Prerequisites Before you start doing practice with various types of examples given in this reference, I'm making an assumption that you are already aware about what is a computer program, and what is a computer programming language? Copyright & Disclaimer © Copyright 2015 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book can retain a copy for future reference but commercial use of this data is not allowed. Distribution or republishing any content or a part of the content of this e-book in any manner is also not allowed without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of our website or its contents including this tutorial. If you discover any errors on our website or in this tutorial, please notify us at [email protected] ii Objective-C Table of Contents About the Tutorial .................................................................................................................................. -

“A Magnetzed Needle and a Steady Hand”

“A Magne)zed Needle and a Steady Hand” Alternaves in the modern world of Integrated Development Environments Jennifer Wood CSCI 5828 Spring 2012 Real Programmers hp://xkcd.com/378/ For the rest of us • Modern Integrated Development Environments (IDE) – A one-stop shop with mul)ple features that can be easily accessed by the developer (without switching modes or ac)vang other u)li)es) to ease the task of creang soYware – A mul)tude of IDEs exist for each programming language (Java, C++, Python, etc.) and each plaorm (desktops, cell phones, web-based, etc.) – Some IDEs can handle mul)ple programming languages, but most are based in just one – There are many good free IDEs out there, but you can also pay for func)onality from $ to $$$$ – IDEs are like opinions, everyone has one and everyone thinks everyone else's s)nks Why are IDEs a good thing? • They aack many of the sources of accidental difficul)es in soYware development by having: – Real-)me protec)on from fault generang typos and bad syntax – High levels of abstrac)on to keep developers from being forced to redevelop basic (and not so basic) classes and structures for every project – IDE increases the power of many development tools by merging them into one that provides “integrated libraries, unified file formats, and pipes and filters. As a result, conceptual structures that in principle could always call, feed, and use one another can indeed easily do so in prac)ce.” (Brooks, 1987). • A core focus of IDE developers is con)nuous improvement in transparency to minimize searching for func)ons -

Programming Java for OS X

Programming Java for OS X hat’s so different about Java on a Mac? Pure Java applica- tions run on any operating system that supports Java. W Popular Java tools run on OS X. From the developer’s point of view, Java is Java, no matter where it runs. Users do not agree. To an OS X user, pure Java applications that ignore the feel and features of OS X are less desirable, meaning the customers will take their money elsewhere. Fewer sales translates into unhappy managers and all the awkwardness that follows. In this book, I show how to build GUIs that feel and behave like OS X users expect them to behave. I explain development tools and libraries found on the Mac. I explore bundling of Java applications for deployment on OS X. I also discuss interfacing Java with other languages commonly used on the Mac. This chapter is about the background and basics of Java develop- ment on OS X. I explain the history of Java development. I show you around Apple’s developer Web site. Finally, I go over the IDEs commonly used for Java development on the Mac. In This Chapter Reviewing Apple Java History Exploring the history of Apple embraced Java technologies long before the first version of Java on Apple computers OS X graced a blue and white Mac tower. Refugees from the old Installing developer tan Macs of the 1990s may vaguely remember using what was tools on OS X called the MRJ when their PC counterparts were busy using JVMs. Looking at the MRJ stands for Mac OS Runtime for Java. -

LAZARUS FREE PASCAL Développement Rapide

LAZARUS FREE PASCAL Développement rapide Matthieu GIROUX Programmation Livre de coaching créatif par les solutions ISBN 9791092732214 et 9782953125177 Éditions LIBERLOG Éditeur n° 978-2-9531251 Droits d'auteur RENNES 2009 Dépôt Légal RENNES 2010 Sommaire A) À lire................................................................................................................5 B) LAZARUS FREE PASCAL.............................................................................9 C) Programmer facilement..................................................................................25 D) Le langage PASCAL......................................................................................44 E) Calculs et types complexes.............................................................................60 F) Les boucles.....................................................................................................74 G) Créer ses propres types..................................................................................81 H) Programmation procédurale avancée.............................................................95 I) Gérer les erreurs............................................................................................105 J) Ma première application................................................................................115 K) Bien développer...........................................................................................123 L) L'Objet..........................................................................................................129 -

B-Human 2018

Team Report and Code Release 2018 Thomas R¨ofer1;2, Tim Laue2, Arne Hasselbring2, Jannik Heyen2, Bernd Poppinga2, Philip Reichenberg2, Enno R¨ohrig2, Felix Thielke2 1 Deutsches Forschungszentrum f¨urK¨unstliche Intelligenz, Enrique-Schmidt-Str. 5, 28359 Bremen, Germany 2 Universit¨atBremen, Fachbereich 3, Postfach 330440, 28334 Bremen, Germany Revision: November 14, 2018 Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 About Us........................................4 1.2 About the Document..................................4 2 Getting Started6 2.1 Download........................................6 2.2 Components and Configurations...........................7 2.3 Building the Code...................................8 2.3.1 Project Generation...............................8 2.3.2 Visual Studio on Windows...........................8 2.3.3 Xcode on macOS................................9 2.3.4 Linux...................................... 10 2.4 Setting Up the NAO.................................. 11 2.4.1 Requirements.................................. 11 2.4.2 Installing the Operating System....................... 12 2.4.3 Creating Robot Configuration Files for a NAO............... 12 2.4.4 Managing Wireless Configurations...................... 13 2.4.5 Installing the Robot.............................. 13 2.5 Copying the Compiled Code.............................. 13 2.6 Working with the NAO................................ 14 2.7 Starting SimRobot................................... 15 2.8 Calibrating the Robots................................. 16 2.8.1 Overall Physical -

Installing a Development Environment

IBM TRIRIGA Anywhere Version 10 Release 4.2 Installing a development environment IBM Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 13. This edition applies to version 10, release 4, modification 2 of IBM TRIRIGA Anywhere and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. © Copyright IBM Corporation 2014, 2015. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Chapter 1. Preparing the IBM TRIRIGA Trademarks .............. 15 Anywhere environment ........ 1 Installing the Android development tools..... 1 Installing the iOS development tools ...... 3 Installing the Windows development tools .... 5 Chapter 2. Installing IBM TRIRIGA Anywhere .............. 7 Chapter 3. Installing an integrated development environment ....... 9 Chapter 4. Deploying apps by using MobileFirst Studio .......... 11 Notices .............. 13 Privacy Policy Considerations ........ 14 © Copyright IBM Corp. 2014, 2015 iii iv Installing a development environment Chapter 1. Preparing the IBM TRIRIGA Anywhere environment Before you can build and deploy the IBM® TRIRIGA® Anywhere Work Task Management app, you must set up the computer on which IBM TRIRIGA Anywhere is installed. Procedure 1. Prepare the environment for building the app: Android Install the Android development tools. iOS Install the iOS development tools. Windows Install the Windows development tools 2. Install IBM TRIRIGA Anywhere 3. Optional: Install an integrated development environment. 4. Deploy the app with MobileFirst Studio. Installing the Android development tools Oracle JDK and Android SDK are required to build Android mobile apps. About this task If you install the integrated development environment, which includes MobileFirst Studio and Eclipse, you must also install the Android Development Tools (ADT) plug-in. -

Introduction to Programming with Xojo, Will Motivate You to Learn More About Xojo Or Any Other Programming Language

Page 1 of 291 Introduction CONTENTS 1. Foreword 2. Acknowledgments 3. Conventions 4. Copyright & License Page 2 of 291 Foreword When you finish this book, you won’t be an expert developer, but you should have a solid grasp on the basic building blocks of writing your own apps. Our hope is that reading Introduction to Programming with Xojo, will motivate you to learn more about Xojo or any other programming language. The hardest programming language to learn is the first one. This book focuses on Xojo - because it’s easier to learn than many other languages. Once you’ve learned one language, the others become easier, because you’ve already learned the basic concepts involved. For example, once you know to write code in Xojo, learning Java becomes much easier, not only because the languages are similar and you already know about arrays, loops, variables, classes, debugging, and more. After all, a loop is a loop in any language. So while this book does focus on Xojo, the concepts that are introduced are applicable to many iii different programming languages. Where possible, some commonalities and differences are pointed out in notes. Before you get started, you’ll need to download and install Xojo to your computer. To do so, visit http://www.xojo.com and click on the download link. Xojo works on Windows, macOS and Linux. It is free to download, develop and test - you only need to buy a license if you want to compile your apps. Page 3 of 291 Acknowledgements Special thanks go out to Brad Rhine who wrote the original versions of this book with help from Geoff Perlman (CEO of Xojo, Inc). -

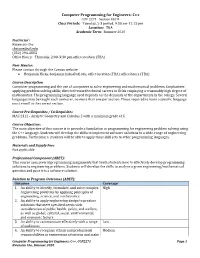

Computer Programming for Engineers: C++ COP 2271 Section EED4 Class Periods: Tuesday, 2-3 Period, 9:30 Am-12:15 Pm Location: TBA Academic Term: Summer 2020

Computer Programming for Engineers: C++ COP 2271 Section EED4 Class Periods: Tuesday, 2-3 period, 9:30 am-12:15 pm Location: TBA Academic Term: Summer 2020 Instructor: Kwansun Cho [email protected] (352) 294-6883 Office Hours: Thursday, 2:00-3:30 pm, office location (TBA) Peer Mentor: Please contact through the Canvas website Benjamin Hicks, [email protected], office location (TBA), office hours (TBA) Course Description Computer programming and the use of computers to solve engineering and mathematical problems. Emphasizes applying problem solving skills; directed toward technical careers in fields employing a reasonably high degree of mathematics. The programming language used depends on the demands of the departments in the college. Several languages may be taught each semester, no more than one per section. Those required to learn a specific language must enroll in the correct section. Course Pre-Requisites / Co-Requisites MAC 2312 - Analytic Geometry and Calculus 2 with a minimum grade of C Course Objectives The main objective of this course is to provide a foundation in programming for engineering problem solving using the C++ language. Students will develop the skills to implement software solutions to a wide-range of engineering problems. Furthermore, students will be able to apply these skill sets to other programming languages. Materials and Supply Fees Not applicable Professional Component (ABET): This course uses several programming assignments that teach students how to effectively develop programming solutions to engineering problems. Students will develop the skills to analyze a given engineering/mathematical question and pose it is a software solution. Relation to Program Outcomes (ABET): Outcome Coverage* 1. -

C Programming Tutorial

C Programming Tutorial C PROGRAMMING TUTORIAL Simply Easy Learning by tutorialspoint.com tutorialspoint.com i COPYRIGHT & DISCLAIMER NOTICE All the content and graphics on this tutorial are the property of tutorialspoint.com. Any content from tutorialspoint.com or this tutorial may not be redistributed or reproduced in any way, shape, or form without the written permission of tutorialspoint.com. Failure to do so is a violation of copyright laws. This tutorial may contain inaccuracies or errors and tutorialspoint provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy of the site or its contents including this tutorial. If you discover that the tutorialspoint.com site or this tutorial content contains some errors, please contact us at [email protected] ii Table of Contents C Language Overview .............................................................. 1 Facts about C ............................................................................................... 1 Why to use C ? ............................................................................................. 2 C Programs .................................................................................................. 2 C Environment Setup ............................................................... 3 Text Editor ................................................................................................... 3 The C Compiler ............................................................................................ 3 Installation on Unix/Linux ............................................................................ -

Install Qt on a Mac with Xcode Or Qtcreator

Install Qt on a Mac with Xcode or QtCreator par Michel LIBERADO Date de publication : 07 february 2009 Dernière mise à jour : 13 february 2009 These few pages show you how to easily install Qt 4.4.3 on a Mac and use it either with Xcode or Qt Creator. Version en français (Version en français disponible) Install Qt on a Mac with Xcode or QtCreator par Michel LIBERADO I - Installing Xcode and compilation tools................................................................................................................... 3 I-A - Information......................................................................................................................................................3 I-B - Installing Xcode..............................................................................................................................................3 II - Installing Qt 4.4.3...................................................................................................................................................6 II-A - Information.....................................................................................................................................................6 II-B - Installing Qt 4.4.3 Mac..................................................................................................................................6 III - Your first compilation from the terminal.............................................................................................................. 11 III-A - Creation of a source file........................................................................................................................... -

Xcode Setup Department of Computer Science & Electrical Engineering

Xcode Setup Department of Computer Science & Electrical Engineering Xcode is an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) provided for free by Apple Inc. to develop Apple Macintosh and Apple iOS applications. While it is optimized for those scenarios, it works well for the types of projects we do in the Computer Science program. An IDE is a development tool consisting of three components: Editor. An editor is a tool designed to help the user create and make changes to a document. A code editor is specifically designed to facilitate writing code. Other common code editors include emacs and vi. Compiler. A compiler translates source code (such as Java or C++) into machine language (such as an .exe or a.out). We use g++ as the compiler in CS 124 and CS 165. Debugger. A debugger is a program that allows the developer to pause execution of program while it is running to see what is going on inside. A debugger enables the developer to look at local variables, see which functions were called (called the “call stack”), peek at memory, and even make changes to the data of the program while it is running. Xcode is an IDE designed to support a wide variety of languages. The “first class” languages include Objective C, C++, and Java. Setup In order to get up-and-running with Xcode, you will need to copy your code to your Mac, install Xcode on your Mac, create a project, link relevant libraries, and run. 1. Copy your files The easiest way to copy your Linux program files to your Mac is with a thumb drive. -

C++ Compact Course

C++ Compact Course Till Niese (Z 705) Alexander Artiga Gonzalez (Z 712) [email protected] [email protected] 9 April 2018 graphics.uni.kn Organizational and Scope Sessions I Day 1 I Day 4 I Overview (CMake, “Hello World!”) I Overloading I Preprocessor, Compiler, Linker I Templates, Inline I STD Library I Default parameters I Input-/Output-Streams I Lambda functions I Day 2 I Day 5 I Stack and Heap I assert, static I Pointer I Compiler flags I Classes I ? I Day 3 I const, constexpr 02 CMake (www.cmake.org) CMake is an open-source, cross-platform family of tools designed to build, test and package software. CMake is used to control the software compilation process using simple platform and compiler independent configuration files, and generate native makefiles and workspaces that can be used in the compiler environment of your choice. 03 CMakeLists.txt cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.7) project(HelloWorld) set(CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD 14) set(SOURCE_FILES main.cpp) add_executable(HelloWorld ${SOURCE_FILES}) Invoke from command-line: $cmake <Path to dir with CMakeLists.txt> $make 04 Popular IDEs with CMake support (selection). IDE: Integrated Development Environment CLion QtCreator Visual Studio KDevelop XCode Linux x x x Windows x x x (x) Mac OS X x x x Free 30 days x x x x Note: Using CLion or QtCreator on Windows requires Cygwin (www.cygwin.com) or MinGW (www.mingw.org) installed. 05 CMake + Visual Studio (Windows) 1. open CMake (gui) 2. “Where is the source code” → select project folder 3. “Where to build binaries” → select build folder (e.g <Project folder>/build) 4.