The Tethered Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visit Inspiration Guide 2017

VISIT INSPIRATION GUIDE 2017 PLEASANTON LIVERMORE DUBLIN DANVILLE Discover Everything The Tri-Valley Has To Offer 2 1 4 5 6 Daytripping in Danville Dublin—Have Fun in Our Backyard Discover Danville’s charming historical downtown. Enjoy the While You’re Away From Yours variety of shops, boutiques, restaurants, cafés, spas, wine Explore our outstanding, family-friendly amenities, including bars, museums, galleries, parks and trails. Start at Hartz and our gorgeous parks (our new aquatic center, “The Wave,” Prospect Avenue-the heart of downtown. You’ll fnd plenty opens in late spring 2017) and hiking trails, quality shopping, of free parking, and dogs are welcome, making Danville the wonderful international cuisine, an iMax theater, Dublin Ranch perfect day trip destination. Visit our website to plan your Robert Trent Jones Jr. golf course, bowling, laser tag, ice upcoming adventure through Danville, and for the historic skating, and a trampoline park. Also, join us for our signature walking tour map of the area. Once you visit Danville we know St. Patrick’s Day Festival. It’s all right here in our backyard. you’ll be back. Visit dublin.ca.gov Visit ShopDanvilleFirst.com Discover Everything The Tri-Valley Has To Offer 3 7 8 Living It Up in Livermore Pleasanton— Livermore is well known for world-class innovation, rich An Extraordinary Experience western heritage, and a thriving wine industry. Enjoy 1,200 acres of parks and open space, 24 miles of trails We offer a wide variety of shopping and dining options— and a round of golf at award-winning Callippe Preserve. -

Jaguar Xj6, Xj12, Xjs Jxj-19

JAGUAR XJ6, XJ12, XJS JXJ-19 UPGRADED VOLTAGE REGULATOR Unlike an original mechanical regulator, this is completely new, solid-state, electronic version encased in an original-style housing. It has load dump protection and adjustable voltage while retaining the original look and connections (NEG- POS-FLD). Voltage is factory-set at 14.2V. The LMAR23 keeps the battery at full charge by managing proper alternator output under changing loads and varying speeds. Maximum field current is increased from 3 to 5 amps to safely yield the most $139.99 from the alternator. XJ6 Series I w/ Butec Alternator C31526 MOSS CLASSIC JAGUAR A “bad old days” relic. Given to Al Moss by members of a local MG club, this license plate was Looking Ahead to the New Normal registered to Al’s MG YB. I used to love telling the story of how to assume or believe things would For the past year plus, we have in our pre computer days, customer materially change. As long as we do operated on a mix of reduced staffing service posted a number in the sales our jobs, the results will follow. and video conferences. The Moss room. That number was how many Then things changed. We all know team has gone all in on keeping things days until an order was likely to be what I mean. As this catalog goes to moving. I cannot say enough about processed. When things got busy, press, we are welcoming in a return the loyalty and dedication of our the number could grow to as high as to normal life. -

Incandescent: Light Bulbs and Conspiracies1

Dr Grace Halden recently completed her PhD at Birkbeck, University of London. Her doctoral research on science fiction brings together her interest in philosophy, technology and literature. She has a range of diverse VOLUME 5 NUMBER 2 SPRING 2015 publications including an edited book Concerning Evil and articles on Derrida and Doctor Who. [email protected] Article Incandescent: 1 Light Bulbs and Conspiracies Grace Halden / __________________________________________ Light bulbs are with us every day, illuminating the darkness or supplementing natural light. Light bulbs are common objects with a long history; they seem innocuous and easily terminated with the flick of a switch. The light bulb is an important invention that, as Roger Fouquet notes, was transformational with regard to industry, economy and the revolutionary ability to ‘live and work in a well-illuminated environment’.2 Wiebe Bijker, in Of Bicycles, Bakelites and Bulbs (1997), explains that light bulbs show an integration between technology and society and how these interconnected advancements have led to a sociotechnical evolution.3 However, in certain texts the light bulb has been portrayed as insidious, controlling, and dehumanising. How this everyday object has been curiously demonised will be explored here. Through looking at popular cultural conceptions of light and popular conspiracy theory, I will examine how the incandescent bulb has been portrayed in dystopian ways.4 By using the representative texts of The Light Bulb Conspiracy (2010), The X-Files (1993-2002), and Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), I will explore how this commonplace object has been used to symbolise the malevolence of individuals and groups, and the very essence of technological development itself. -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

The Safeguards of Privacy Federalism

THE SAFEGUARDS OF PRIVACY FEDERALISM BILYANA PETKOVA∗ ABSTRACT The conventional wisdom is that neither federal oversight nor fragmentation can save data privacy any more. I argue that in fact federalism promotes privacy protections in the long run. Three arguments support my claim. First, in the data privacy domain, frontrunner states in federated systems promote races to the top but not to the bottom. Second, decentralization provides regulatory backstops that the federal lawmaker can capitalize on. Finally, some of the higher standards adopted in some of the states can, and in certain cases already do, convince major interstate industry players to embed data privacy regulation in their business models. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: US PRIVACY LAW STILL AT A CROSSROADS ..................................................... 2 II. WHAT PRIVACY CAN LEARN FROM FEDERALISM AND FEDERALISM FROM PRIVACY .......... 8 III. THE SAFEGUARDS OF PRIVACY FEDERALISM IN THE US AND THE EU ............................... 18 1. The Role of State Legislatures in Consumer Privacy in the US ....................... 18 2. The Role of State Attorneys General for Consumer Privacy in the US ......... 28 3. Law Enforcement and the Role of State Courts in the US .................................. 33 4. The Role of National Legislatures and Data Protection Authorities in the EU…….. .............................................................................................................................................. 45 5. The Role of the National Highest Courts -

Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal a Publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association

NYSBA SUMMER 2005 | VOLUME 16 |NO. 2 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association Remarks From the Chair/Editor’s Note Remarks From the Chair In continuing with the theme of excellence among It is with a sad heart that EASL members, I am extremely pleased that Elisabeth I write to say that one of our Wolfe, Chair of our Pro Bono Committee, received one longtime Executive Commit- of the NYSBA President’s Pro Bono Service Awards. We tee members, James Henry are so proud of all of Elisabeth’s accomplishments, Ellis, who most recently Co- which help to make available pro bono opportunities for Chaired with Jason Baruch our members and their pro bono clients, and for raising our Theater and Performing EASL’s pro bono activities and programs to a nationally Arts Committee, passed recognized level. The President’s Pro Bono Service away on May 26th, at the age Awards were created more than ten years ago to honor of seventy-two. When I law firms, law students and attorneys from each judicial spoke with his daughter and district who have provided outstanding pro bono serv- asked if there was a specific ice to low income people. Elissa D. Hecker organization to which dona- In addition, our new Committee on Alternate Dis- tions could be made in Jim’s pute Resolution has launched itself with programs name, she mentioned the Parsons Dance Foundation. already held and many more underway. In addition, its Jim will be missed. -

Basic Use of Your Iphone and Ipad Bobby Adams for Ocala Mac User�S Group 19 June 2017

Basic Use of Your iPhone and iPad Bobby Adams for Ocala Mac Users Group 19 June 2017 1 References/Resources ! Apple Websites: www.apple.com/ipad & www.apple.com/support/ipad ! Wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/iPad ! YouTube: Search for iPad ! Search Engines (Google, Bing, and Yahoo, etc.) ! Mass Media: (Books, Magazine, Internet, etc.) ! iPad the Missing Manual, 7th. Edition by David Pogue ! My iPad 8th. Ed. By Gary Rosenzweig ! iPad for Dummies 7th. Edition by Nancy Muir ! And, many others… ! Personal Opinion… 2 Reference Books 3 Reference Books 4 References 5 Reference Books 6 Reference Books 7 Reference 8 Reference Book 9 10 New iOS 10.3 iPhone User’s Guide 11 New iOS 10.3 iPad User’s Guide 12 What is an iPhone? 13 What iPhone Do You Have? Model Released iOS Cameras Processor Connector iPhone 2007 1.0 No ARM1176 30-pin iPhone 3G 2008 2.0 2 ARM1176 30-pin iPhone 3GS 2009 3.0 2 ARM A8 30-pin iPhone 4 2010 4.0 2 ARM A8 30-pin iPhone 4S 2011 5.0 2 A9 30-pin iPhone 5 2012 6.0 2 Swift Lightning iPhone 5S/5C 2013 7.0 2 Swift Lightning iPone 6/6P 2014 8.0 2 A8 Lightning iPhone 6S/6SP 2015 9.0 2 A8 Lightning iPhone SE/7/7P 2016 10.0 3 A10X Lightning iPhone X ? Lightning 14 What is an iPad? 15 What is an iPad? 16 What iPad Do You Have? Model Released Display Retina Processor Connector (inches) Display iPad 4/2010 9.7 No A4 30-pin iPad 2 3/2011 9.7 No A5 30-pin 3rd Gen 3/2012 9.7 Yes A5X 30-pin 4th Gen 11/2012 9.7 Yes A6X Lightning iPad mini 1st Gen 12/2012 7.9 No A5 Lightning iPad Air 11/2013 9.7 Yes A7 Lightning iPad mini 2 11/2013 7.9 Yes A7 -

A Model Regime of Privacy Protection

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2006 A Model Regime of Privacy Protection Daniel J. Solove George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel J. Solove & Chris Jay Hoofnagle, A Model Regime of Privacy Protection, 2006 U. Ill. L. Rev. 357 (2006). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOLOVE.DOC 2/2/2006 4:27:56 PM A MODEL REGIME OF PRIVACY PROTECTION Daniel J. Solove* Chris Jay Hoofnagle** A series of major security breaches at companies with sensitive personal information has sparked significant attention to the prob- lems with privacy protection in the United States. Currently, the pri- vacy protections in the United States are riddled with gaps and weak spots. Although most industrialized nations have comprehensive data protection laws, the United States has maintained a sectoral approach where certain industries are covered and others are not. In particular, emerging companies known as “commercial data brokers” have fre- quently slipped through the cracks of U.S. privacy law. In this article, the authors propose a Model Privacy Regime to address the problems in the privacy protection in the United States, with a particular focus on commercial data brokers. Since the United States is unlikely to shift radically from its sectoral approach to a comprehensive data protection regime, the Model Regime aims to patch up the holes in ex- isting privacy regulation and improve and extend it. -

The Federal Trade Commission and Consumer Privacy in the Coming Decade

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 2007 The Federal Trade Commission and Consumer Privacy in the Coming Decade Joseph Turow University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Chris Hoofnagle UC Berkeley School of Law, Berkeley Center for Law and Technology Deirdre K. Mlligan Samuelson Law, Technology & Public Policy Clinic and the Clinical Program at the Boalt Hall School of Law Nathaniel Good School of Information at the University of California, Berkeley Jens Grossklags School of Information at the University of California, Berkeley Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Turow, J., Hoofnagle, C., Mulligan, D., Good, N., and Grossklags, J. (2007-08). The Federal Trade Commission and Consumer Privacy in the Coming Decade, I/S: A Journal Of Law And Policy For The Information Society, 724-749. This article originally appeared as a paper presented under the same title at the Federal Trade Commission Tech- ade Workshop on November 8, 2006. The version published here contains additional information collected during a 2007 survey. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/520 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Federal Trade Commission and Consumer Privacy in the Coming Decade Abstract The large majority of consumers believe that the term “privacy policy” describes a baseline level of information practices that protect their privacy. In short, “privacy,” like “free” before it, has taken on a normative meaning in the marketplace. When consumers see the term “privacy policy,” they believe that their personal information will be protected in specific ways; in particular, they assume that a website that advertises a privacy policy will not share their personal information. -

Acquisition of a Majority Stake in Canyon

Acquisition of a majority stake in Canyon December 2020 2 Letter from the founder “When I saw our first bike on the Tour de France, a childhood dream came true, however, I knew that this was just the beginning. CANYON is built on a foundation of passion and self-sacrifice, with the ultimate goal of being the best bicycle company in the world. In the beginning, a lot of people told us that selling bikes online was impossible. We have proven everybody wrong! We are pioneers in building a fundamentally superior business model and consumer experience which our competitors simply can’t replicate. Our brand today represents the same core values of performance, innovation, community and quality as it did in 1985. This has only been possible thanks to our team. Always passionate, industry-leading and driven by the same goal, building the best and sharing the passion. We are uniquely positioned to take advantage of this huge and growing market with ever more support from recent global events. Our plan will take us to €1bn in sales over the next five years, but our vision remains the same. Canyon is the best bicycle company in the world. We invite GBL to join us as we become the largest.” - Roman Arnold, Founder & Chairman of the Advisory Board 3 Canyon is in line with structural trends which guide GBL’s investment decisions Health awareness Consumer experience Digitalization & technology Sustainability and resource scarcity 4 Introduction to the transaction • GBL has signed a definitive agreement to acquire a majority stake in Canyon • Canyon is -

PBS' NOVA Sciencenow NAMES DAVID POGUE AS NEW HOST

PBS’ NOVA scienceNOW NAMES DAVID POGUE AS NEW HOST FOR SCIENCE MAGAZINE SERIES IN 2012 Renowned New York Times Tech Reporter to Join Critically Acclaimed Series in Launch of Season 6 This Fall on PBS Stations Nationwide Produced for PBS by the March 15, 2012 — NOVA scienceNOW has named David Pogue, WGBH Science Unit popular technology reporter for The New York Times, to host the critically acclaimed science magazine series, senior executive producer Paula S. Apsell announced today. Pogue has signed on to the series beginning this fall with the launch of Season 6, premiering in October 2012 at 10 pm ET/PT on PBS. David Pogue is already a familiar face to audiences of the flagship NOVA series, with recent stints hosting the highly watched fourhour miniseries on materials science, Making Stuff (PBS, 2011), viewed by 14 milion people, and the upcoming twohour special program, Hunting the Elements, premiering on NOVA on April 4, 2012. Pogue is the third host tapped to helm the acclaimed series. Prior hosts include TV and radio news correspondent Robert Krulwich, who originated the role for the series’ inaugural season in January 2005, and astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, who took the reins in October 2006 and hosted seasons two through five. “We are thrilled for David to join the NOVA scienceNOW team as host, reporting stories from the frontiers of science and technology,” said Apsell.“David’s engaging personality and tireless enthusiasm, as well as his natural curiosity as a tech journalist, all add up to a passion for storytelling and -

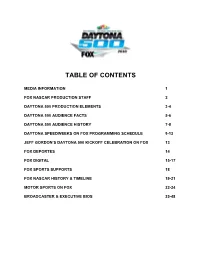

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb.