Civil Rights Groups Demand Airbnb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

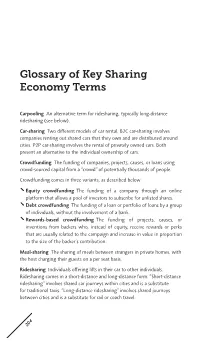

Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms

Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms Carpooling An alternative term for ridesharing, typically long-distance ridesharing (see below). Car-sharing Two different models of car rental. B2C car-sharing involves companies renting out shared cars that they own and are distributed around cities. P2P car-sharing involves the rental of privately owned cars. Both present an alternative to the individual ownership of cars. Crowdfunding The funding of companies, projects, causes, or loans using crowd-sourced capital from a “crowd” of potentially thousands of people. Crowdfunding comes in three variants, as described below. Equity crowdfunding The funding of a company through an online platform that allows a pool of investors to subscribe for unlisted shares. Debt crowdfunding The funding of a loan or portfolio of loans by a group of individuals, without the involvement of a bank. Rewards-based crowdfunding The funding of projects, causes, or inventions from backers who, instead of equity, receive rewards or perks that are usually related to the campaign and increase in value in proportion to the size of the backer’s contribution. Meal-sharing The sharing of meals between strangers in private homes, with the host charging their guests on a per seat basis. Ridesharing Individuals offering lifts in their car to other individuals. Ridesharing comes in a short-distance and long-distance form. “Short-distance ridesharing” involves shared car journeys within cities and is a substitute for traditional taxis. “Long-distance ridesharing” involves shared journeys between cities and is a substitute for rail or coach travel. 204 Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms 205 Sharing economy (condensed version) The value in taking underutilized assets and making them accessible online to a community, leading to a reduced need for ownership of those assets. -

The Airbnb Story – Page 1

The Airbnb Story – Page 1 THE AIRBNB STORY How Three Ordinary Guys Disrupted an Industry, Made Billions...and Created Plenty of Controversy LEIGH GALLAGHER LEIGH GALLAGHERis an assistant managing editor at Fortune where she writes and edits feature stories. She is also the host of Fortune Live, Fortune.com's weekly video show. Leigh Gallagher is a co-chair of the Fortune Most Powerful Women Summit and also oversees Fortune's 40 Under 40 multi-platform editorial franchise. She appears regularly as a business news commentator on many TV shows including CBS's This Morning and Face the Nation, public radio's Marketplace, MSNBC's Morning Joe, CNBC and CNN. She is the author of two books including The End of the Suburbs and is a visiting scholar at New York University. She is a graduate of Cornell University. ISBN 978-1-77544-909-6 SUMMARIES.COM empowers you to get 100% of the ideas from an entire business book for 10% of the cost and in 5% of the time. Hundreds of business books summarized since 1995 and ready for immediate use. Read less, do more. www.summaries.com The Airbnb Story – Page 1 1. Looking for the next big thing design blogs they knew all the attendees would be assumption these conferences could easily max out a reading. They refined this idea for weeks, and the more hotel's supply of rooms and they decided the perfect they talked about it, the more they realized it was so place to launch would be for the upcoming South by The Airbnb story began in Providence, Rhode Island in weird that it just might work—and with a looming Southwest conference in Austin, Texas. -

Convening Innovators from the Science and Technology Communities Annual Meeting of the New Champions 2014

Global Agenda Convening Innovators from the Science and Technology Communities Annual Meeting of the New Champions 2014 Tianjin, People’s Republic of China 10-12 September Discoveries in science and technology are arguably the greatest agent of change in the modern world. While never without risk, these technological innovations can lead to solutions for pressing global challenges such as providing safe drinking water and preventing antimicrobial resistance. But lack of investment, outmoded regulations and public misperceptions prevent many promising technologies from achieving their potential. In this regard, we have convened leaders from across the science and technology communities for the Forum’s Annual Meeting of the New Champions – the foremost global gathering on innovation, entrepreneurship and technology. More than 1,600 leaders from business, government and research from over 90 countries will participate in 100- plus interactive sessions to: – Contribute breakthrough scientific ideas and innovations transforming economies and societies worldwide – Catalyse strategic and operational agility within organizations with respect to technological disruption – Connect with the next generation of research pioneers and business W. Lee Howell Managing Director innovators reshaping global, industry and regional agendas Member of the Managing Board World Economic Forum By convening leaders from science and technology under the auspices of the Forum, we aim to: – Raise awareness of the promise of scientific research and highlight the increasing importance of R&D efforts – Inform government and industry leaders about what must be done to overcome regulatory and institutional roadblocks to innovation – Identify and advocate new models of collaboration and partnership that will enable new technologies to address our most pressing challenges We hope this document will help you contribute to these efforts by introducing to you the experts and innovators assembled in Tianjin and their fields of research. -

Airbnb: Managing Trust and Safety on a Platform Business

Irish Journal of Management • 39(2) • 2020 • 126-134 DOI: 10.2478/ijm-2020-0004 Irish Journal of Management Airbnb: Managing trust and safety on a platform business Teaching article Caoimhe Walsh, Deepak Saxena* and Laurent Muzellec Trinity Business School, Trinity College Dublin Abstract: AirBnB has become a preferred accommodation marketplace for the travellers around the world. AirBnB is a two-sided digital platform that connects guests and hosts. In so doing, it creates value for both sides of the platform. Guests save money on the accommodation and hosts get earnings from their otherwise idle space. The case follows the company from the inception to its growth and current challenges with wider community. The case helps to understand the key features of digital platforms: how do they create value for all users; how do they shape value propositions for two sides, and how does the community become a stakeholder in the platform business. It also focuses on the issue of trust and the need for the company to integrate the concerns of other stakeholders such as communities and local authorities. Finally, the case highlights the impact of Covid-19 on the company and the travel industry. Keywords: digital platform, multi-sided platform, value proposition, business model, trust © Sciendo INTRODUCTION AirBnB is a digital accommodation marketplace providing access to 7 million places to stay in more than 100,000 cities and 220 countries/regions around the world1. It does this by connecting the owners of accommodation (referred to as hosts) with customers (guests) who would like to use this accommodation on their travels. -

An Analysis of the Changing Competitive Landscape in the Hotel Industry Regarding Airbnb Dean D

Dominican University of California Dominican Scholar Master's Theses and Capstone Projects Theses and Capstone Projects 5-2015 An Analysis of the Changing Competitive Landscape in the Hotel Industry Regarding Airbnb Dean D. Lehr Dominican University of California Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.dominican.edu/masters-theses Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation Lehr, Dean D., "An Analysis of the Changing Competitive Landscape in the Hotel Industry Regarding Airbnb" (2015). Master's Theses and Capstone Projects. Paper 188. This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Capstone Projects at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MBA 5180 Capstone Thesis Project An Analysis of the Changing Competitive Landscape in the Hotel Industry Regarding Airbnb” By Dean Lehr M.B.A. Dominican University, 2015 1 Executive Summary This capstone thesis project is an analysis of the competitive environment between the hotel industry and Airbnb, an Online Vacation Rental Platform, (OVRP) in San Francisco. Airbnb is an internet platform that facilitates hosts to rent shared space, a private room or an entire home. Airbnb is growing and currently has over 1M listings in 34,000 cities and 190 countries globally. The focus of this research to identify the competition within the San Francisco market, including data from the hotel and OVRP industry New York City, NY, Los Angeles, CA, and USA. -

California's 154 Billionaires Saw Net Worth Jump $175.4 Billion— 25.5

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: June 29, 2020 California’s 154 Billionaires Saw Net Worth Jump $175.4 Billion— 25.5% in First Three Months of COVID-19 Pandemic Growth in Billionaire Wealth a Stark Contrast to Recently Passed CA Budget Which Cuts Health & Vital Services of Vulnerable Californians in Absence of Federal Revenue, and Congress Stalls on New COVID-19 Financial Aid Package. Along with Federal Funds, Taxing the Windfall of the Ultra-Rich Could Raise Revenues Needed to Prevent Billions in Scheduled & Trigger Cuts to Medi-Cal & Many Other Programs. New Report Lists All 154 Billionaires and Their Profits in Just Three Months While Over 5 Million Californians Lost Jobs, and 5,000 Have Died from COVID-19. Grassroots Surge of Support for Budget Equity in California, With Many Events Planned for this Week WASHINGTON/CALIFORNIA—At the same time that the California Legislature was debating billions of dollars of budget cuts to health and other vital services during a pandemic and an economic downturn, California’s 154 billionaires collectively saw their wealth increase by $175.4 billion or 25.5% during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a new report by Americans for Tax Fairness (ATF), Health Care for America Now (HCAN) and Health Access California. Another 11 Californians were newly minted billionaires during the same period. Coming on the heels of a new California state budget that has billions of cuts deferred, scheduled, and subject to triggers, unless needed federal aid comes through, the new data provides a powerful argument for health, education, and other advocates seeking new federal funds and new state revenues, including taxes on the wealthiest, in order to prevent cuts and make needed investments in a time of great need. -

Michael / Ström Dom Maklerski S.A. & the Swan School

MICHAEL / STRÖM DOM MAKLERSKI S.A. & THE SWAN SCHOOL Milion złotych. Dlaczego studia na Ivy League tyle kosztują? Spis treści 01 Wstęp . 03 02 Studia na Ivy League . 04 A Całkowity roczny koszt studiowania . 07 B Co otrzymuje student za 45 tysięcy dolarów czesnego? . 10 C Porównanie zasobów uniwersytetów w Stanach Zjednoczonych, Wielkiej Brytanii i Polsce . 12 D Czy stypendia na Ivy League to mit? . 14 E Trendy i najpopularniejsze kierunki studiów . 16 F Przyszły rynek pracy a studia na amerykańskich uniwersytetach . 17 G Dyplom Ivy League to przynależność do klubu wartości . 19 03 Zwrot z inwestycji, czyli zarobki po studiach . 21 04 Źródła danych . 23 Z wielką przyjemnością oddajemy w Państwa ręce raport na na jednej z tych szkół daje również możliwość znalezienia pracy temat studiów na najlepszych uczelniach w Stanach Zjedno- w najlepszych firmach – nawet już podczas studiów. Leszek Traczyk czonych. Został on przygotowany przez nas wspólnie z The W raporcie porównaliśmy sposób funkcjonowania uczelni z Ligi Swan School, szkołą oferującą kompleksowe przygotowanie Bluszczowej. Dzięki lekturze dowiedzą się Państwo, które uczel- Członek zarządu do studiów za granicą. Podjęliśmy się zadania współtworzenia nie zajęły wysokie miejsca w zestawieniu, co studenci uzyskują w Michael/Ström Dom Maklerski tego raportu, ponieważ jesteśmy przekonani, że wspieranie w ramach czesnego, jakimi zasobami dysponują uczelnie oraz Prywatnie ojciec dwójki dzieci – dzieci w wyborze ścieżki rozwoju jest dla rodziców jednym jakie są najpopularniejsze kierunki studiów. Informacje zawarte dorosłej córki Magdy, kończącej z najważniejszych zadań, jakie podejmują w życiu. Materiał w raporcie mogą się okazać przydatne przy podejmowaniu właśnie studia z rachunkowości stanowi ważny element naszych wspólnych działań w obszarze decyzji o tym, która szkoła może najlepiej odpowiadać oczeki- i finansów oraz 17-letniego syna „Inwestowanie w Edukację”. -

TRANSITIONS of TRUST ACROSS DIFFERENT BUSINESS CONTEXT: IMPACT of the SHARING ECONOMY on the LODGING INDUSTRY by Sungsik Yoon Ba

TRANSITIONS OF TRUST ACROSS DIFFERENT BUSINESS CONTEXT: IMPACT OF THE SHARING ECONOMY ON THE LODGING INDUSTRY By Sungsik Yoon Bachelor of Science in Tourism Management Kyonggi University, South Korea 2009 Master of Science in Hospitality Business Michigan State University 2011 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy – Hospitality Administration William F. Harrah College of Hotel Administration The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2017 © Copyright 2017 by Sungsik Yoon All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT TRANSITIONS OF TRUST ACROSS DIFFERENT BUSINESS CONTEXT: IMPACT OF THE SHARING ECONOMY ON THE LODGING INDUSTRY by Sungsik Yoon Dr. Mehmet Erdem, Committee Chair Associate Professor of Hotel Administration University of Nevada, Las Vegas Airbnb’s influence has been growing fast in the recent few years, and hotel operators are beginning to recognize the competitive threat they pose. Consumers may have a different perception of Airbnb than hoteliers themselves do. Thus, the current study attempts to explore hotel customers’ perceptions of the sharing economy business (Airbnb). Also, it is important to pay attention to the different business settings of the channels currently in the lodging industry: hotel-brand.com and OTAs are set in the Business-to-consumer (B2C) context while Airbnb is set in a Consumer-to-consumer (C2C) context. Moreover, investigating the relationship between trust and perceived risk in this new channel (i.e., Airbnb) is arguably of great significance due to the inherent risk of transactions on Airbnb, especially when compared with traditional B2C. Considering Airbnb business belongs to a different context (C2C) than traditional hotels do (B2C), this study uses a mixed methods approach, specifically with an exploratory sequential design in order to thoroughly examine the relationships among trust and perceived risk, those antecedents, perceived benefit, and intention to select Airbnb over traditional hotels or resorts. -

Learning from Billion Dollar Startups

Learning From Billion Dollar Startups Why Startups Like Uber, Xiaomi, Airbnb and Slack Succeed August, 2015 Uncopyright 2015. By Thomas Oppong This ebook is uncopyrighted. Feel free to take passages from it and replicate them online. Use the content however you want! Email it, share it, with or without credit. Attribution is appreciated but not required. If you want to take my work and improve upon it, as artists have been doing for centuries, I think that’s a wonderful thing. Other books by Thomas Oppong Start. Make. Create. Do. Building Smarter Habits Idea To Startup Growth A Smart New Mind I also exist outside of this ebook. Founder at Alltopstartups.com (free resources, advice and tools for startups) Curator at Postanly.com (a free weekly newsletter that delivers the most insightful and long form thought-provoking posts from top publishers) Contributor at Entrepreneur.com Get to know me: Facebook (Follow my updates), Twitter (Mostly startup and productivity tweets), LinkedIn (Strictly business updates). Download my latest FREE ebook Failed startup Lessons (Why over 50 Startups Failed to Make it) Contents Intro The One Reason Why Startups Succeed Xiaomi: China's Smartphone Sensation Why Uber is Booming Growth Story of Snapchat How Palantir Built a Billion Dollar Intelligence Software SpaceX: How Failure Creates Success The Rise of Pinterest How Airbnb Disrupted The Hotel Economy Why Dropbox is Successful How WeWork is Transforming Office Life How Theranos is Turning the Lab Industry Upside Down How Spotify Dominated Music Streaming How DJI Became world's Most Popular Consumer Drone Maker The Growth Strategy of Square How Zenefits Disrupted Human Resources Why Stripe’s Payment Platform is so Popular The Real Reason Slack Became a billion dollar Company so fast Lyft Is On An Upward Trajectory How Houzz Became an Industry-Changing Business How Blue Apron is Disrupting the Traditional Grocery Chain Model The Fabulous Story of JustFab How Jessica Alba’s Honest Co. -

Ten Years of Airbnb Phenomenon Research: a Bibliometric Approach (2010–2019)

sustainability Article Ten Years of Airbnb Phenomenon Research: A Bibliometric Approach (2010–2019) Julia M. Núñez-Tabales, Miguel Ángel Solano-Sánchez * and Lorena Caridad-y-López-del-Río Faculty of Law and Business and Economic Sciences, University of Cordoba, Puerta Nueva s/n, 14002 Cordoba, Spain; [email protected] (J.M.N.-T.); [email protected] (L.C.-y.-L.-d.-R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 11 July 2020; Accepted: 30 July 2020; Published: 1 August 2020 Abstract: The interest in the Airbnb phenomenon is represented in the fast growth of publications indexed in the Web of Science (WoS) since the research inception of this topic in 2010. However, there are no studies that analyze the incidence of this phenomenon from a bibliometric approach using WoS. Therefore, this paper aims to quantify the incidence and composition of the Airbnb phenomenon through bibliometrics taken it as a data source. To achieve this aim, the WoS statistical instruments and the bibliometric tool VOSviewer are used. The results obtained, such as the number of articles and citations per year, the main categories of these articles, the nationalities of the authors, the most productive institutions, the sources and authors in terms of publications, and the H-Core of the most cited articles, are presented. Finally, concept maps are exposed, representing the relatedness of co-authorship and co-citation among authors, as well as the co-occurrence of the keywords in the articles analyzed. Satisfaction, trust, and innovation appear as the main research lines. This paper can be useful for academics and professionals, giving them a holistic overview of the topic, identifying new research areas, or as an objective manner to literary review approaches. -

Becoming One of the Most Valuable New Venture in the World

Becoming one of the most valuable new venture in the world A study on how such ventures arise Final thesis, June 22nd, 2016 Name: Lisa Boschma Student number: 11092963 Qualification: MSc in Business Administration – Entrepreneurship & Innovation Institution: University of Amsterdam Supervisor: dr. Ileana Maris – de Bresser Second reader: dr. Wietze van der Aa Statement of originality This document is written by Student Lisa Boschma who declares to take full responsibility for the contents of this document. I declare that the text and the work presented in this document is original and that no sources other than those mentioned in the text and its references have been used in creating it. The Faculty of Economics and Business is responsible solely for the supervision of completion of the work, not for the contents. Table of contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Literature review .............................................................................................................................. 9 2.1 Nature of opportunities ................................................................................................................. 9 2.2 Entrepreneurial approaches ........................................................................................................ -

The Impact of Design Thinking on Education: the Case of Active Learning Lab

Master Degree programme in INNOVATION & MARKETING “Second Cycle (D.M 270/2004)” The impact of Design Thinking on education: The case of Active Learning Lab Supervisor Ch.Prof.Vladi Finotto Graduand Nicolò Canestraro 861064 Academic Year 2016/2017 1 A mia madre, colei che mi ha dato tutto 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION _________________________________ 7 1. DESIGN THINKING _____________________________ 9 1.1 Design definition ______________________________________ 10 1.2 Design Thinking roadmap _______________________________ 12 1.3 Design Thinking and its features _________________________ 18 1.3.1 Design Thinking perspective _____________________________ 18 1.4 Creativity ____________________________________________ 22 1.5 Framework and rules __________________________________ 26 1.6 Process _____________________________________________ 27 1.6.1 The Model of “3 I” ____________________________________ 29 1.7 Design Thinking in the sphere of firm ______________________ 33 1.7.1 P&G _____________________________________________ 33 1.7.2 Airbnb ____________________________________________ 36 1.7.3 IDEO _____________________________________________ 38 1.7.3.1 The field of wealth and wellness __________________________ 40 1.7.3.2 The field of government _______________________________ 41 1.7.3.3 The field of consumer goods and services ___________________ 43 4 1.8 The criticisms of Design Thinking _________________________ 44 2. DESIGN THINKING EDUCATION _________________ 46 2.1 The schools of Design Thinking __________________________