Studbook Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

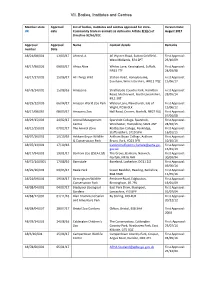

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

Captive Elephants in Japan: Census and History Kako Y

Elephant Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 3 9-6-1986 Captive Elephants in Japan: Census and History Kako Y. Yonetani Zoo Design and Education Lab, ZooDEL Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/elephant Recommended Citation Yonetani, K. Y. (1986). Captive Elephants in Japan: Census and History. Elephant, 2(2), 3-14. Doi: 10.22237/elephant/1521731978 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Elephant by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Captive Elephants in Japan: Census and History Cover Page Footnote Special thanks to the following cooperators on this survey (Associate members/Japanese Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums): Fumiyoshi Nakayama (Animal care keeper, Yagiyama Zoological Park- Sendai) Kenjiro Nagase (Zoo veterinarian, Osaka Municipal Tennoji Zoo) Teruaki Hayashi (Zoo veterinarian, Nanki Shirahama Adventure World; member of the Elephant Interest Group). In addition, information received from: Shoichi Hashimoto (Curator, Kobe-Oji Zoo), Kaoru Araki and Takashi Saburi (Animal care keeper and Zoo veterinarian, Takarazuka Zoological and Botanical Gardens), Gi-ichiro Kondou (Animal care manager, Koshien Hanshin Park), Shingo Nagata (Zoo verterinarian, Misaki Park Zoo and Aquarium), Tatsuo Abe (Superintendent, Gunma Safari World), Ikuo Kurihara (Zoo veterinarian, Akiyoshidai Safari Land), Yoshiaki Ikeda (Public relations unit, Nogeyama Zoological Gardens of Yokohama), Sachi Hamanaka (Public relations unit, Fuji Safari Park), Takeshi Ishikawa (A.N.C. New York, USA), Kofu Yuki Park Zoo, African Safari, Miyazaki Safari Park, and Elza Wonderland. I am indebted to Ken Kawata (General curator, Milwaukee County Zoo, USA, member of the Elephant Interest Group) for his unselfish help with this article. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

The Behavioral Ecology of the Tibetan Macaque

Fascinating Life Sciences Jin-Hua Li · Lixing Sun Peter M. Kappeler Editors The Behavioral Ecology of the Tibetan Macaque Fascinating Life Sciences This interdisciplinary series brings together the most essential and captivating topics in the life sciences. They range from the plant sciences to zoology, from the microbiome to macrobiome, and from basic biology to biotechnology. The series not only highlights fascinating research; it also discusses major challenges associ- ated with the life sciences and related disciplines and outlines future research directions. Individual volumes provide in-depth information, are richly illustrated with photographs, illustrations, and maps, and feature suggestions for further reading or glossaries where appropriate. Interested researchers in all areas of the life sciences, as well as biology enthu- siasts, will find the series’ interdisciplinary focus and highly readable volumes especially appealing. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15408 Jin-Hua Li • Lixing Sun • Peter M. Kappeler Editors The Behavioral Ecology of the Tibetan Macaque Editors Jin-Hua Li Lixing Sun School of Resources Department of Biological Sciences, Primate and Environmental Engineering Behavior and Ecology Program Anhui University Central Washington University Hefei, Anhui, China Ellensburg, WA, USA International Collaborative Research Center for Huangshan Biodiversity and Tibetan Macaque Behavioral Ecology Anhui, China School of Life Sciences Hefei Normal University Hefei, Anhui, China Peter M. Kappeler Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology Unit, German Primate Center Leibniz Institute for Primate Research Göttingen, Germany Department of Anthropology/Sociobiology University of Göttingen Göttingen, Germany ISSN 2509-6745 ISSN 2509-6753 (electronic) Fascinating Life Sciences ISBN 978-3-030-27919-6 ISBN 978-3-030-27920-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27920-2 This book is an open access publication. -

Population from Ethiopia

A genetically distinct lion (Panthera leo) population from Ethiopia Barnett, Ross Published in: European Journal of Wildlife Research Publication date: 2013 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Barnett, R. (2013). A genetically distinct lion (Panthera leo) population from Ethiopia. European Journal of Wildlife Research. Download date: 26. sep.. 2021 Eur J Wildl Res DOI 10.1007/s10344-012-0668-5 ORIGINAL PAPER A genetically distinct lion (Panthera leo) population from Ethiopia Susann Bruche & Markus Gusset & Sebastian Lippold & Ross Barnett & Klaus Eulenberger & Jörg Junhold & Carlos A. Driscoll & Michael Hofreiter Received: 29 September 2011 /Revised: 9 September 2012 /Accepted: 18 September 2012 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2012 Abstract Lion (Panthera leo) numbers are in serious decline in 15 lions from Addis Ababa Zoo in Ethiopia. A comparison and two of only a handful of evolutionary significant units with six wild lion populations identifies the Addis Ababa lions have already become extinct in the wild. However, there is as being not only phenotypically but also genetically distinct continued debate about the genetic distinctiveness of different from other lions. In addition, a comparison of the mitochon- lion populations, a discussion delaying the initiation of con- drial cytochrome b (CytB) gene sequence of these lions to servation actions for endangered populations. Some lions sequences of wild lions of different origins supports the notion from Ethiopia are phenotypically distinct from other extant of their genetic uniqueness. Our examination of the genetic lions in that the males possess an extensive dark mane. In this diversity of this captive lion population shows little effect of study, we investigated the microsatellite variation over ten loci inbreeding. -

Laboratory Primate Newsletter

LABORATORY PRIMATE NEWSLETTER Vol. 45, No. 3 July 2006 JUDITH E. SCHRIER, EDITOR JAMES S. HARPER, GORDON J. HANKINSON AND LARRY HULSEBOS, ASSOCIATE EDITORS MORRIS L. POVAR, CONSULTING EDITOR ELVA MATHIESEN, ASSISTANT EDITOR ALLAN M. SCHRIER, FOUNDING EDITOR, 1962-1987 Published Quarterly by the Schrier Research Laboratory Psychology Department, Brown University Providence, Rhode Island ISSN 0023-6861 POLICY STATEMENT The Laboratory Primate Newsletter provides a central source of information about nonhuman primates and re- lated matters to scientists who use these animals in their research and those whose work supports such research. The Newsletter (1) provides information on care and breeding of nonhuman primates for laboratory research, (2) dis- seminates general information and news about the world of primate research (such as announcements of meetings, research projects, sources of information, nomenclature changes), (3) helps meet the special research needs of indi- vidual investigators by publishing requests for research material or for information related to specific research prob- lems, and (4) serves the cause of conservation of nonhuman primates by publishing information on that topic. As a rule, research articles or summaries accepted for the Newsletter have some practical implications or provide general information likely to be of interest to investigators in a variety of areas of primate research. However, special con- sideration will be given to articles containing data on primates not conveniently publishable elsewhere. General descriptions of current research projects on primates will also be welcome. The Newsletter appears quarterly and is intended primarily for persons doing research with nonhuman primates. Back issues may be purchased for $5.00 each. -

De Communicatie Van Nederlandse Dierentuinen Met Betrekking Tot Het Houden Van Wilde Dieren in De Dierentuin

De communicatie van Nederlandse dierentuinen met betrekking tot het houden van wilde dieren in de dierentuin Afstudeeronderzoek voor de afdeling communicatiewetenschap van de Wageningen Universiteit, als onderdeel van de Master International Development Studies Door: Angela ten Veen Registratie nummer: 860626 854 100 Contact gegevens: [email protected] / [email protected] Vakcode: COM-80433 Begeleiders: ir. Hanneke Nijland en Prof. dr. Noëlle Aarts Datum: Juni 2013 Voorwoord In mijn zoektocht naar een onderwerp voor mijn Master scriptie voor de opleiding International Development Studies in de zomer van 2011 stuitte ik op het onderwerp ‘communicatie strategie van dierentuinen’ op de website van de leerstoelgroep communicatiewetenschappen. Doordat ik zelf een zekere ambiguïteit ervaar als het gaat om dierentuinen was ik zeer geïnteresseerd en gemotiveerd dit onderwerp verder te onderzoeken. Ik ben gek op dieren en dierentuinen maken het mogelijk dieren te ontmoeten die ik normaliter niet snel zal tegenkomen, omdat deze dieren van oorsprong in het wild voorkomen. De ambiguïteit ervaar ik rond het feit dat in de dierentuin wilde dieren leven in gevangenschap en dus niet in hun natuurlijke leefgebied. Dit roept vragen bij mij op als hoe beïnvloeden de leefomstandigheden in de dierentuin gedrag, gezondheid en welzijn van wilde dieren? Aan de ene kant vind ik het leuk dierentuinen te bezoeken omdat zij wilde dieren meer toegankelijk maken, maar aan de andere kant maak ik mij zorgen om hun welzijn. Dit onderzoek heeft een deel van mijn ervaren ambiguïteit weggenomen doordat het me een beter inzicht in dierentuinen heeft gegeven en hun communicatie over het houden van wilde dieren in de dierentuin. -

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits

North American Zoos with Mustelid Exhibits List created by © birdsandbats on www.zoochat.com. Last Updated: 19/08/2019 African Clawless Otter (2 holders) Metro Richmond Zoo San Diego Zoo American Badger (34 holders) Alameda Park Zoo Amarillo Zoo America's Teaching Zoo Bear Den Zoo Big Bear Alpine Zoo Boulder Ridge Wild Animal Park British Columbia Wildlife Park California Living Museum DeYoung Family Zoo GarLyn Zoo Great Vancouver Zoo Henry Vilas Zoo High Desert Museum Hutchinson Zoo 1 Los Angeles Zoo & Botanical Gardens Northeastern Wisconsin Zoo & Adventure Park MacKensie Center Maryland Zoo in Baltimore Milwaukee County Zoo Niabi Zoo Northwest Trek Wildlife Park Pocatello Zoo Safari Niagara Saskatoon Forestry Farm and Zoo Shalom Wildlife Zoo Space Farms Zoo & Museum Special Memories Zoo The Living Desert Zoo & Gardens Timbavati Wildlife Park Turtle Bay Exploration Park Wildlife World Zoo & Aquarium Zollman Zoo American Marten (3 holders) Ecomuseum Zoo Salomonier Nature Park (atrata) ZooAmerica (2.1) 2 American Mink (10 holders) Bay Beach Wildlife Sanctuary Bear Den Zoo Georgia Sea Turtle Center Parc Safari San Antonio Zoo Sanders County Wildlife Conservation Center Shalom Wildlife Zoo Wild Wonders Wildlife Park Zoo in Forest Park and Education Center Zoo Montana Asian Small-clawed Otter (38 holders) Audubon Zoo Bright's Zoo Bronx Zoo Brookfield Zoo Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Dallas Zoo Denver Zoo Disney's Animal Kingdom Greensboro Science Center Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens 3 Kansas City Zoo Houston Zoo Indianapolis -

EAZA NEWS Zoo Nutrition 4

ZOO NUTRITION EAZANEWS 2008 publication of the european association of zoos and aquaria september 2008 — eaza news zoo nutrition issue number 4 8 Feeding our animals without wasting our planet 10 Sustainability and nutrition of The Deep’s animal feed sources 18 Setting up a nutrition research programme at Twycross Zoo 21 Should zoo food be chopped? 26 Feeding practices for captive okapi 15 The development of a dietary review team 24 Feeding live prey; chasing away visitors? EAZA Zoonutr5|12.indd 1 08-09-2008 13:50:55 eaza news 2008 colophon zoo nutrition EAZA News is the quarterly magazine of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) issue 4 Managing Editor Jeannette van Benthem ([email protected]) Editorial staff for EAZA News Zoo Nutrition Issue 4 Joeke Nijboer, Andrea Fidgett, Catherine King Design Jantijn Ontwerp bno, Made, the Netherlands Printing Drukkerij Van den Dool, Sliedrecht, the Netherlands ISSN 1574-2997. The views expressed in this newsletter are not necessarily those of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria. Printed on TREE-FREE paper bleached without chlorine and free from acid who is who in eaza foreword EAZA Executive Committee Although nourishing zoo animals properly and according chair Leobert de Boer, Apenheul Primate Park vice-chair Simon Tonge, Paignton Zoo secretary Eric Bairrao Ruivo, Lisbon Zoo treasurer Ryszard Topola, Lodz Zoo to their species’ needs is a most basic requirement to chair eep committee Bengt Holst, Copenhagen Zoo chair membership & ethics maintain sustainable populations in captivity, zoo and committee Lars Lunding Andersen, Copenhagen Zoo chair aquarium committee aquarium nutrition has been a somewhat underestimated chair legislation committee Jurgen Lange, Berlin Zoo Ulrich Schurer, Wuppertal Zoo science for a long time. -

In Our Hands: the British and UKOT Species That Large Charitable Zoos & Aquariums Are Holding Back from Extinction (AICHI Target 12)

In our hands: The British and UKOT species that Large Charitable Zoos & Aquariums are holding back from extinction (AICHI target 12) We are: Clifton & West of England Zoological Society (Bristol Zoo, Wild Places) est. 1835 Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust (Jersey Zoo) est. 1963 East Midland Zoological Society (Twycross Zoo) est. 1963 Marwell Wildlife (Marwell Zoo) est. 1972 North of England Zoological Society (Chester Zoo) est. 1931 Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (Edinburgh Zoo, Highland Wildlife Park) est. 1913 The Deep est. 2002 Wild Planet Trust (Paignton Zoo, Living Coasts, Newquay Zoo) est. 1923 Zoological Society of London (ZSL London Zoo, ZSL Whipsnade Zoo) est. 1826 1. Wildcat 2. Great sundew 3. Mountain chicken 4. Red-billed chough 5. Large heath butterfly 6. Bermuda skink 7. Corncrake 8. Strapwort 9. Sand lizard 10. Llangollen whitebeam 11. White-clawed crayfish 12. Agile frog 13. Field cricket 14. Greater Bermuda snail 15. Pine hoverfly 16. Hazel dormouse 17. Maiden pink 18. Chagos brain coral 19. European eel 2 Executive Summary: There are at least 76 species native to the UK, Crown Dependencies, and British Overseas Territories which Large Charitable Zoos & Aquariums are restoring. Of these: There are 20 animal species in the UK & Crown Dependencies which would face significant declines or extinction on a global, national, or local scale without the action of our Zoos. There are a further 9 animal species in the British Overseas Territories which would face significant declines or extinction without the action of our Zoos. These species are all listed as threatened on the IUCN Red List. There are at least 19 UK animal species where the expertise of our Zoological Institutions is being used to assist with species recovery. -

2016 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT AND THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR & CEO .......................... 03 A YEAR IN REVIEW JANUARY ....................................... 04 FEBRUARY....................................... 05 MARCH .......................................... 06 APRIL .............................................. 08 JUNE .............................................. 14 JULY................................................ 14 AUGUST.......................................... 15 OCTOBER ....................................... 15 NOVEMBER .................................... 16 DECEMBER ..................................... 17 VISION NATIONAL SECRETARIAT COMMUNICATIONS .......................18 Museums are valued public institutions MEMBERSHIP ...................................18 that inspire understanding and CMA INSURANCE PROGRAM.........19 encourage solutions for a better world. CMA RETAIL PROGRAM ..................19 MUSEUMS FOUNDATION OF CANADA .........................................20 PARTNERS ........................................20 FINANCES .......................................21 FINANCIAL STATEMENT ...................22 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT AND THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR & CEO Dear Members and Supporters: t is the Association’s 70th anniversary and we have so much to take pride in. However it is not a cliché to say this has been a very Iproductive year with its own challenges. The essential values of our association remain today and they are grounded in the very