Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Near & Middle East

February 2021 February The Near & Middle East A Short List of Books, Maps & Photographs Maggs Bros. Ltd. Maggs Bros. MAGGS BROS. LTD. 48 BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON WC1B 3DR & MAGGS BROS. LTD. 46 CURZON STREET LONDON W1J 7UH Our shops are temporarily closed to the public. However, we are still processing sales by our website, email and phone; and we are still shipping books worldwide. Telephone: +44 (0)20 7493 7160 Email: [email protected] Website: www.maggs.com Unless otherwise stated, all sales are subject to our standard terms of business, as displayed in our business premises, and at http://www.maggs.com/terms_and_conditions. To pay by credit or debit card, please telephone. Cover photograph: item 12, [IRAQ]. Cheques payable to Maggs Bros Ltd; please enclose invoice number. Ellipse: item 21, [PERSIA]. THE ARABIAN PENINSULA Striking Oil in Abu Dhabi 1 [ABU DHABI]. VARIOUS AUTHORS. A collection of material relating to the discovery of oil in Abu Dhabi. [Including:] ABU DHABI MARINE AREAS LTD. Persian Gulf Handbook. Small 8vo. Original green card wrappers, stapled, gilt lettering to upper wrapper; staples rusted, extremities bumped, otherwise very good. [1], 23ff. N.p., n.d., but [Abu Dhabi, c.1954]. [With:] GRAVETT (Guy). Fifteen original silver-gelatin photographs, mainly focusing on the inauguration of the Umm Shaif oilfield. 9 prints measuring 168 by 216mm and 6 measuring 200 by 250mm. 14 with BP stamps to verso and all 15 have duplicated typescript captions. A few small stains, some curling, otherwise very good. Abu Dhabi, 1962. [And:] ROGERS (Lieut. Commander J. A.). OFF-SHORE DRILLING. -

Protest and State–Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa

SIPRI Policy Paper PROTEST AND STATE– 56 SOCIETY RELATIONS IN October 2020 THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI is an independent international institute dedicated to research into conflict, armaments, arms control and disarmament. Established in 1966, SIPRI provides data, analysis and recommendations, based on open sources, to policymakers, researchers, media and the interested public. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. GOVERNING BOARD Ambassador Jan Eliasson, Chair (Sweden) Dr Vladimir Baranovsky (Russia) Espen Barth Eide (Norway) Jean-Marie Guéhenno (France) Dr Radha Kumar (India) Ambassador Ramtane Lamamra (Algeria) Dr Patricia Lewis (Ireland/United Kingdom) Dr Jessica Tuchman Mathews (United States) DIRECTOR Dan Smith (United Kingdom) Signalistgatan 9 SE-169 72 Solna, Sweden Telephone: + 46 8 655 9700 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.sipri.org Protest and State– Society Relations in the Middle East and North Africa SIPRI Policy Paper No. 56 dylan o’driscoll, amal bourhrous, meray maddah and shivan fazil October 2020 © SIPRI 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of SIPRI or as expressly permitted by law. Contents Preface v Acknowledgements vi Summary vii Abbreviations ix 1. Introduction 1 Figure 1.1. Classification of countries in the Middle East and North Africa by 2 protest intensity 2. State–society relations in the Middle East and North Africa 5 Mass protests 5 Sporadic protests 16 Scarce protests 31 Highly suppressed protests 37 Figure 2.1. -

Nationwide School Assessment Libya Ministry

Ministry of Education º«∏©àdGh á«HÎdG IQGRh Ministry of Education Nationwide School Assessment Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report - 2012 Assessment Report School Nationwide Libya LIBYA Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report 2012 Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report 2012 º«∏©àdGh á«HÎdG IQGRh Ministry of Education Nationwide School Assessment Libya © UNICEF Libya/2012-161Y4640/Giovanni Diffidenti LIBYA: Doaa Al-Hairish, a 12 year-old student in Sabha (bottom left corner), and her fellow students during a class in their school in Sabha. Doaa is one of the more shy girls in her class, and here all the others are raising their hands to answer the teacher’s question while she sits quiet and observes. The publication of this volume is made possible through a generous contribution from: the Russian Federation, Kingdom of Sweden, the European Union, Commonwealth of Australia, and the Republic of Poland. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the donors. © Libya Ministry of Education Parts of this publication can be reproduced or quoted without permission provided proper attribution and due credit is given to the Libya Ministry of Education. Design and Print: Beyond Art 4 Printing Printed in Jordan Table of Contents Preface 5 Map of schools investigated by the Nationwide School Assessment 6 Acronyms 7 Definitions 7 1. Executive Summary 8 1.1. Context 9 1.2. Nationwide School Assessment 9 1.3. Key findings 9 1.3.1. Overall findings 9 1.3.2. Basic school information 10 1.3.3. -

CONTEMPORARY CHINA: a BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R Margins 0.9") by Lynn White

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R margins 0.9") by Lynn White This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of the seminars WWS 576a/Pol. 536 on "Chinese Development" and Pol. 535 on "Chinese Politics," as well as the undergraduate lecture course, Pol. 362; --to provide graduate students with a list that can help their study for comprehensive exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not too much should be made of this, because some such books may be too old for students' purposes or the subjects may not be central to present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan. Students with specific research topics should definitely meet Laird Klingler, who is WWS Librarian and the world's most constructive wizard. This list cannot cover articles, but computer databases can. Rosemary Little and Mary George at Firestone are also enormously helpful. Especially for materials in Chinese, so is Martin Heijdra in Gest Library (Palmer Hall; enter up the staircase near the "hyphen" with Jones Hall). Other local resources are at institutes run by Chen Yizi and Liu Binyan (for current numbers, ask at EAS, 8-4276). Professional bibliographers are the most neglected major academic resource at Princeton. -

Pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia The Nomadic Tribes of Arabia The nomadic pastoralist Bedouin tribes inhabited the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam around 700 CE. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Describe the societal structure of tribes in Arabia KEY TAKEAWAYS Key Points Nomadic Bedouin tribes dominated the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam. Family groups called clans formed larger tribal units, which reinforced family cooperation in the difficult living conditions on the Arabian peninsula and protected its members against other tribes. The Bedouin tribes were nomadic pastoralists who relied on their herds of goats, sheep, and camels for meat, milk, cheese, blood, fur/wool, and other sustenance. The pre-Islamic Bedouins also hunted, served as bodyguards, escorted caravans, worked as mercenaries, and traded or raided to gain animals, women, gold, fabric, and other luxury items. Arab tribes begin to appear in the south Syrian deserts and southern Jordan around 200 CE, but spread from the central Arabian Peninsula after the rise of Islam in the 630s CE. Key Terms Nabatean: an ancient Semitic people who inhabited northern Arabia and Southern Levant, ca. 37–100 CE. Bedouin: a predominantly desert-dwelling Arabian ethnic group traditionally divided into tribes or clans. Pre-Islamic Arabia Pre-Islamic Arabia refers to the Arabian Peninsula prior to the rise of Islam in the 630s. Some of the settled communities in the Arabian Peninsula developed into distinctive civilizations. Sources for these civilizations are not extensive, and are limited to archaeological evidence, accounts written outside of Arabia, and Arab oral traditions later recorded by Islamic scholars. Among the most prominent civilizations were Thamud, which arose around 3000 BCE and lasted to about 300 CE, and Dilmun, which arose around the end of the fourth millennium and lasted to about 600 CE. -

PDF Du Chapitre

Ruth Finnegan Oral Literature in Africa Open Book Publishers 10. Topical and Political Songs Publisher: Open Book Publishers Place of publication: Open Book Publishers Year of publication: 2012 Published on OpenEdition Books: 7 February 2014 Serie: World Oral Literature Series Electronic ISBN: 9781906924720 http://books.openedition.org Electronic reference FINNEGAN, Ruth. 10. Topical and Political Songs In: Oral Literature in Africa [online]. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2012 (generated 26 avril 2021). Available on the Internet: <http:// books.openedition.org/obp/1197>. ISBN: 9781906924720. 10. Topical and Political Songs Topical and local poetry. Songs of political parties and movements: Mau Mau hymns; Guinea R.D.A. songs; Northern Rhodesian party songs. It has been well said that oral poetry takes the place of newspapers among non-literate peoples. Songs can be used to report and comment on current affairs, for political pressure, for propaganda, and to reflect and mould public opinion. This political and topical function can be an aspect of many of the types of poetry already discussed—work songs, lyric, praise poetry, even at times something as simple as a lullaby—but it is singled out for special discussion in this chapter. It is of particular importance to draw attention to this and to give a number of examples because of the common tendency in studies of African verbal art to concentrate mainly on the ‘traditional’—whether in romanticizing or in deprecating tone—and to overlook its topical functions, especially its significance in contemporary situations. There have been a few admirable exceptions to this attitude to African oral literature, notably Tracey and others associated with the African Music Society (see esp. -

Performances of Border: Theatre and the Borders of Germany, 1980-2015

Performances of Border: Theatre and the borders of Germany, 1980-2015 A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Misha Hadar IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIERMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Adviser: Professor Margaret Werry November 2020 COPYRIGHT © 2020 MISHA HADAR Acknowledgements I could not have written this dissertation without my advisor Margaret Werry, whose support and challenge throughout this process, the space and confidence she offered, made this possible. I want to thank my committee members: Michal Kobialka, Sonja Kuftinec, Hoon Song and Matthias Rothe. You have been wonderful teachers to me, people to think with, models to imagine a life of scholarship, and friends through a complicated process. I want to thank the rest of the Theatre Arts and Dance department at the University of Minnesota, who were a wonderful intellectual community to me. And then all of my graduate student friends, from the department and beyond, who were there to think this project with me, to listen, to question, and to encourage. Special thanks in this to my cohort, Sarah Sadler, my first base in Minneapolis Bryan Schmidt, and Baruch Malewich. I want to thank family, near and further away, who were important and kind support. And finally, to my wonderful partner Elif Kalaycioglu, with whom this whole rollercoaster has been shared, and who was always there to push and pull us along. i Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER I: The Turkish Ensemble and the Cultural Border .................................... 21 CHAPTER II: Transit Europa and the Historiographic Border ................................. 104 CHAPTER III: The First Fall of the European Wall, Compassion, and the Humanitarian Border ................................................................................................... -

Vol. 2, No. 1 (Trinity 2018)

Vol. 2, No. 1 (Trinity 2018) Th e 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force and America’s Endless War Harrison Akins Th e Intersection of the Bosnian War, the Mujahideen, and Counterterrorism Measures in Bosnia and Herzegovina Nicola Mathieson Th e Quest for Islam in a Virtual Maze: How the Internet is Shaping Religious Knowledge among Young Muslims in Berlin-Kreuzberg Ines Gassal-Bosch Arab, Unionist, Republican: Th e Case of Ma'rūf al-Ruṣāfī Chris Hitchcock Memories and Narrations of “Nations” Past: Accounts of Early Migrants from Kerala in the Gulf in the Post-Oil Era M. H. Ilias 1 Oxford Middle East Review Vol. 2, No. 1 (Trinity 2018) Copyright © 2018 OMER | Oxford Middle East Review. All rights reserved. Senior Member Prof Eugene Rogan Managing Editors Krystel De Chiara, St Antony’s College Alexis Nicholson, St Antony’s College Section Editors Ameer Al-Khudari, St Antony’s College Ivo Bantel, St Antony’s College Manuel Giardino, Magdalen College Allison Holle, Exeter College Amaan Merali, St Cross College Bahar Saba, Wadham College Marral Shamshiri-Fard, St Antony’s College Chief Copy Editors Ceighley Cribb, St Antony’s College Naomi Lester, St Anne’s College Treasurer Naomi Lester, St Anne’s College Public Relations Manager Timo Schmidt, St Antony’s College Production Manager Allison Holle, Exeter College Events Manager Jeremy Jacobellis, Exeter College 2 Oxford Middle East Review is a non-partisan project that seeks to bring together a wide range of individuals with different backgrounds, beliefs, ideas, aspirations, viewpoints, and methodologies, while sharing an adherence to principles of equality, social justice, freedom of speech, and tolerance. -

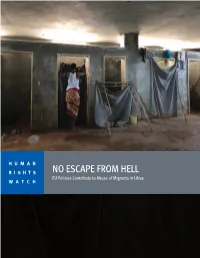

NO ESCAPE from HELL EU Policies Contribute to Abuse of Migrants in Libya WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS NO ESCAPE FROM HELL EU Policies Contribute to Abuse of Migrants in Libya WATCH No Escape from Hell EU Policies Contribute to Abuse of Migrants in Libya Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36994 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JANUARY 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36994 “No Escape from Hell” EU Policies Contribute to Abuse of Migrants in Libya Map .................................................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 1 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 8 Methodology -

Towards E-Learning in Higher Education in Libya

Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology Volume 7, 2010 Towards E-Learning in Higher Education in Libya Amal Rhema and Iwona Miliszewska Victoria University, Melbourne, Victoria [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The growing influence of technologies on all aspects of life, including the education sector, re- quires developing countries to follow the example of the developed countries and adopt technol- ogy in their education systems. Although relatively late, the Libyan government has eventually responded to this challenge and started investing heavily in the reconstruction of its education system, and initiating national programs to introduce information and communication technology (ICT) into education. In addition, there are plans to establish virtual campuses in many universi- ties and colleges to provide an advanced platform for learners and instructors. This paper presents the higher education context in Libya and outlines the applications of ICT and e-learning in Lib- yan higher education to date. It discusses the issues that need be considered and addressed in adopting ICT in the learning and teaching processes including technological infrastructure, cur- riculum development, cultural and language aspects, and management support. The paper also outlines the prospects for the integration of e-learning into Libyan higher education and con- cludes with proposing an integrated approach to advancing the introduction of e-learning in Libya. Keywords: developing country, e-learning, ICT teacher training, information and communication technology, Libyan higher education, technology transfer, technological infrastructure. Introduction Libya has the highest literacy rate in the Arab world, and the United Nation’s Human Develop- ment Index, which ranks standard of living, social security, health care and other factors for de- velopment, keeps Libya at the top of all African countries. -

The Issues of Teaching English in Libyan Higher Education

Changing Practices in a Developing Country: The Issues of Teaching English in Libyan Higher Education PhD Thesis Mohamed Abushafa This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Art, Design & Humanities De Montfort University April 2014 i Declaration I, Mohamed Abushafa, declare that the main text of this thesis entitled Changing Practices in a Developing Country: The Issues of Teaching English in Libyan Higher Education is entirely my own work. This work has not been previously submitted wholly or in part for any academic award or qualification other than that for which it is now submitted. i Abstract Libya is a country which is trying to find its place in the international community. It has a mainly youthful population of about 5.6 million with a median age of 24.8 years and large numbers of young people are accessing university courses. This creates a demand for university places which is increasingly difficult to meet. The recent political changes in Libya have compounded these difficulties. This study investigates the challenges of teaching English in Libyan Higher Education as the country prepares its young people for living and working in a global environment where the English language is predominant. The investigation finds that there is recognition of the importance of English, but the level of language skills of students entering university is well below an acceptable standard, and both teachers and students advocate an early start for learning English in schools. Within the universities the curriculum is not consistent and leads to graduates in English having a limited command of the language. -

Perceptions of Selected Libyan English As a Foreign

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace PERCEPTIONS OF SELECTED LIBYAN ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEACHERS REGARDING TEACHING OF ENGLISH IN LIBYA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri–Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctorate of Philosophy By YOUSSIF ZAGHWANI OMAR Dr. Amy A. Lannin, Dissertation Supervisor Dr. Roy F. Fox, Dissertation Co-Supervisor December 2014 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled PERCEPTIONS OF SELECTED LIBYAN TEACHERS OF ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE REGARDING TEACHING OF ENGLISH IN LIBYA Presented by YOUSSIF ZAGHWANI OMAR, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ______________________________________ Dr. Amy Lannin, Chair _____________________________________ Dr. Roy Fox, Co-Chair ______________________________________ Dr. Carol Gilles ______________________________________ Dr. Matthew Gordon DEDICATION To my main reason of being in this world, my dear MOM and my late DAD . To my partner in life, my beloved WIFE . To my vision to the future, my KIDS . To the soul of my late nephew, MOHAMED . To my great adviser, Dr. AMY LANNIN . To my helpful co-adviser, Dr. ROY FOX . To my committee, Dr. MATTHEW GORDON and Dr. CAROL GILLES . To the dean of College of Education, Dr. JOHN LANNIN . To my family in Libya . To my close friends in the United States, DAVID, LANCE, DENNIS . To my colleagues in English Education Department. I humbly dedicate this work.