Copyright by Vijay Parthasarathy 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Cricket Poster

India ODI Strike Rate Sachin Sourav Rahul R Tendulkar C Ganguly Dravid Mohammad Yuvraj Virender Mahendra Azharuddin Singh Sehwag S Dhoni Sunil Mohammad Virat Vinod Alaysinhji Kapil M Gavaskar Kaif Kohli G Kambli D Jadeja Dev Manoj Rohit Irfan Nayan Ajit VangipurappuM VPrabhakarG Sharma K Pathan R Mongia B Agarkar S Laxman Dillip Navjot Javagal Yashpal Hemang Yusuf Robin B Vengsarkar Dinesh Srinath Sharma K Badani K Pathan V Uthappa S Sidhu Mongia Rabindra Roger M Woorkeri Kiran Praveen Raman Sunil S More K Amre R Singh Lamba H Binny V Raman B Joshi Harbhajan Singh Syed M Saba Ajinkya Hrishikesh Ashok Nikhil H Kirmani Karim M Rahane H Kanitkar Chopra Suresh Malhotra Gautam Zaheer Khan K Raina Sameer Brijesh Bapu K Yalaka Vijay Chandrakant S Dighe P PatelVenkatesh PrasadVenugopal Rao Dahiya Gambhir S Pandit Krishna K Chetan Sanjay D Karthik Sharma Murali Atul Jacob Chetandra P Rohan Amay Vijay C Bedade J Martin S ChauhanS GavaskarR Khurasiya V Manjrekar Ravindra Reetinder S Sodhi A Jadeja AshishRavichandranArunLakshmipathyVijay Arshad Vikram Nehra Ashwin Lal Balaji Yadav Ayub Gundappa S Rathore R Viswanath Gagan Surinder Syed Ajay Vakkadai Sandeep Praveen AmarnathAbid Ali RatraB Chandrasekhar Sanjay Vijay R K Khoda M Patil Kumar R Bhardwaj Pathiv B Bangar Sridharan Jai SanjeevSubramaniamMunaf Krishnamachari Farokh SriramP YadavK SharmaBadrinathM Patel Ravishankar A Patel Ajay M Engineer Surinder Rajesh Jatin K Sharma K Chauhan Ajit ManinderIshantSarandeepAshok Kirtivardhan C Khanna KarsanL WadekarV ParanjpeSinghSharmaSinghV Mankad J Shastri -

![A Hz]] Cv^RZ R[Vjr Drjd DYRY](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4457/a-hz-cv-rz-r-vjr-drjd-dyry-214457.webp)

A Hz]] Cv^RZ R[Vjr Drjd DYRY

0 1 )+%,)-./01 SIDISrtVUU@IB!&!!"&#S@B9 D< %#!E IV69P99I !%! %! ' -$(./ $)*+, $(% 9 % '( <= ))* =>? !"# $"% @ #&5)4)4% 9+;;%:B:'4$!,%" 4:A"):B% $$%!&#%' '%! C*):$)1 44:'4%594):!)+!)*> 5:)!:+4B+49 '%' %!(%' '%! 2 34256./7/8/D * *+ 854$#'5) & )" 0123. ) 4 & && &+ 48$91+ polls, they said. Exhorting the workers and oining for itself the term party leaders in the National C'ajeya BJP' (invincible BJP), Executive Meeting here, the first and dubbing the Opposition's after the passing away of its bid to forge a patriarch Atal Bihari Vajpayee, 'Mahagathbandhan' a dhakosla to work for achieving greater ! (eye wash) and a 'Bhraanti' goals, the party president said # (illusion), the ruling party on the BJP would return to power !$ Saturday resolved to return to in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan power in 2019 with a larger and Chhattisgarh and also do % L mandate and gave its president well in Mizoram where elec- %' L Amit Shah an extended run till tions are due by the year-end. P Q% the general elections by defer- In Telangana too Shah said the # ! ring its organisational polls. party will go full steam. * % + + For his part, Shah pointed Delivering the inaugural % to the BJP's growing clout in address in the meeting which # # the country and of India in the was attended by all the top %' ! global league under Prime leaders including the Prime %% + Minister Narendra Modi who, Minster, State Chief Ministers, ' %, he said, leads the party and not State presidents and most of the -..! follows like his predecessor members of the National Manmohan Singh. Hitting Executive, Shah said the party !# Q out at the Congress, Shah also would contest the 2019 poll on , said while the BJP believed in the plank of 'good governance' NO1N 'Making India', the Congress of the Modi Government from ) && " * + " & % ! trusts in 'Breaking India.” 2014 to 2019. -

Uninhibited India Eyes Russian Kamov

Follow us on: facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No.2016/1957, REGD NO. SSP/LW/NP-34/2016-18 @TheDailyPioneer instagram.com/dailypioneer/ Established 1864 OPINION 8 Published From WORLD 12 SPORT 15 DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL NO PLACE FOR KAVANAUGH SWORN IN AS ARSENAL THRASH BHUBANESWAR RANCHI RAIPUR MINORITIES IN PAKISTAN US SUPREME COURT JUSTICE FULHAM 5-1 IN PL CHANDIGARH DEHRADUN Late City Vol. 154 Issue 271 LUCKNOW, MONDAY OCTOBER 8, 2018; PAGES 16 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable RHEA EXCITED ABOUT DEBUT OF} SARA KHAN} 14 VIVACITY www.dailypioneer.com Naxalism will be Uninhibited India eyes Russian Kamov wiped out in 2-3 Country has independent foreign policy, says Army chief in reaction to US sanction threat PNS n NEW DELHI “allies or partners.” questions. However, an indus- years: Rajnath * Russians are keen on “The (CAATSA presiden- try source said the law is n a clear indication that associating with Indian tial) waiver is narrow, intend- ambiguous about “when a India was not going to buck- defence forces: Rawat ed to wean countries off waiver is necessary so this can The Home Minister said he I PNS n le under the threat of US sanc- * Army chief had held talks with Russian equipment and allow be avoided for years”. LUCKNOW was confident that the speed tion over the S-400 missile deal Russian military officials on for things such as spare parts The National Defense and accuracy with which the with Russia, Army chief Gen enhancing bilateral for previously-purchased Authorization ACT (NDDA) iving credit to the Central CRPF was operating, the men- Bipin Rawat on Sunday said cooperation equipment,” a White House 2019 gives the president the GReserve Police Force ace of Naxalism would be the country has an indepen- National Security Council power to waive of the CAAT- (CRPF) for curbing terrorism wiped out within 2-3 years. -

MIND-BOGGLING TALENT He Creates Visual Works of Wonder, Through His Own Imagination and His Inner Eye, for the Rest of Us to See

WEDNESDAY 29 NOVEMBER 2017 CAMPUS | 3 ENTERTAINMENT | 11 DPS-MIS English Zakir Hussain and Language Teachers Rakesh Chaurasia attend TEFL to perform workshop at NCPA P | 4-5 MIND-BOGGLING TALENT He creates visual works of wonder, through his own imagination and his inner eye, for the rest of us to see. It’s wonderful, when there’s this art that we’re all familiar with from our children’s birthday parties, that takes it to such a scale that it boggles the mind: Rebecca Hoffberger 03 WEDNESDAY 29 NOVEMBER 2017 CAMPUS TNG holds collaborative events with neighbouring schools ymbolising the message of love, Nebras International school kinder- harmony and togetherness, gartners and TNG campus students Skindergarten students of The in Al Nuaija branch were welcomed Next Generation (TNG) School vis- by the Newton International school ited different schools in Doha to and King’s College Doha celebrate the Universal Children’s Kindergartners. Day Week. The day was marked to The young leaders of TNG pre- promote rights and welfare of the pared greeting cards and a The students then actively par- student exchange programme. children. delightful performance for the host ticipated in the class activities There hospitality is much appre- TNG school organised a week schools. arranged by the host schools. ciated and we hope to work long programme to visit the neigh- On reaching the premises, TNG “These collaborative events together in future projects”, said bouring schools to meet and greet kindergarten students were cor- with other schools bring us closer TNG Principal Ms Qudsia Asad their fellow kindergarteners. -

Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler a Dissertati

Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Chair Ann Anagnost Stevan Harrell Danny Hoffman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology ©Copyright 2018 Darren T. Byler University of Washington Abstract Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Department of Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies This study argues that Uyghurs, a Turkic-Muslim group in contemporary Northwest China, and the city of Ürümchi have become the object of what the study names “terror capitalism.” This argument is supported by evidence of both the way state-directed economic investment and security infrastructures (pass-book systems, webs of technological surveillance, urban cleansing processes and mass internment camps) have shaped self-representation among Uyghur migrants and Han settlers in the city. It analyzes these human engineering and urban planning projects and the way their effects are contested in new media, film, television, photography and literature. It finds that this form of capitalist production utilizes the discourse of terror to justify state investment in a wide array of policing and social engineering systems that employs millions of state security workers. The project also presents a theoretical model for understanding how Uyghurs use cultural production to both build and refuse the development of this new economic formation and accompanying forms of gendered, ethno-racial violence. -

Indian Stand-Up Comedians and Their Fight Against India's Anti

Universität Potsdam Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Abschlussarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Master of Education (M.Ed.) Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Dirk Wiemann Zweitgutachterin: Dr. Tania Meyer Comedy as Resistance: Indian Stand-Up Comedians and Their Fight Against India’s Anti-Democratic Tendencies Lea Sophie Nüske Master: Englisch und Französisch auf Lehramt Matrikelnr.: 765845 Selbstständigkeitserklärung Hiermit versichere ich, Lea Nüske, dass ich die Masterarbeit selbstständig und nur mit den angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmitteln angefertigt habe. Alle Stellen der Arbeit, die ich aus diesen Quellen und Hilfsmitteln dem Wortlaut oder dem Sinne nach entnommen habe, sind kenntlich gemacht und im Literaturverzeichnis aufgeführt. Berlin, den 3. August 2018 Lea Nüske Zusammenfassung Die vorliegende Arbeit Comedy as Resistance – Indian Stand-Up Comedians and Their Fight Against India’s Anti-Democratic Tendencies beschäftigt sich mit der Frage, ob und inwiefern Stand-Up Comedy in Indien als Mittel zum sozio-politischen Widerstand genutzt wird und wie weitreichend dieser Widerstand einzuschätzen ist. Um diese Frage zu beantworten werden zunächst die Merkmale des Genres sowie ihre Funktionen untersucht, um herauszustellen, weshalb sich besonders Stand-Up Comedy dafür eignet, indirekten politischen Widerstand zu leisten. Auch die Geschichte des satirischen Widerstandes und des Genres Stand-Up Comedy im indischen Kontext sowie die soziale Spaltung der Gesellschaft, die durch verschiedene Konflikte zum Ausdruck gebracht wird -

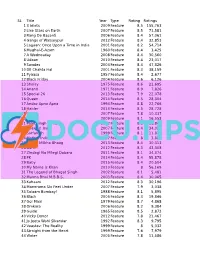

Aspirational Movie List

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. -

November, 2009

One-hit Wonders Cultural Calendar for November 2009 For some actors, instant stardom peters out and they end up being remembered for just the first film. Here’s a list taken H from India’s Bollywood. November 9 November 25 Film: Sampoorn Ramayan (In Hindi) Talk – World heritage site of Hampi, Karnataka Debut film being a smash hit at the turnstiles is what every Venue & Time: ICC 5.30 p.m. Duration:3 hrs by Dr. M. S. Nagraj Rao, Former Director actor dreams of. It is tragic when this aspiration doesn’t General of Archaeological Survey of India translate into reality. More tragic when the launch vehicle Venue & Time: ICC 6.00 p.m. (To be confirmed) November 14 S delivers but the subsequent flicks do not garner similar Painting, Drawing and Essay Competition for commercial success or critical acclaim. To this category belong children to commemorate the birth anniversary of November 27 several Bollywood stars who created a storm with their first Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru Bharatha Natyam Recital offering. But their subsequent releases bombed at the box Venue & Time: ICC 9.30 a.m. by Deepal Gunasena, Shanmuga Sharma office. November 2009 Jayaprakash Sharma Dinuka Gunasekara & E An apt example of this mishap is Kumar Gaurav whose maiden November 20 Thilini Dhanapala students of Ms. Vasugy film, Love Story set new box office records in the early Panel discussion on “Governing the Commons in Jegatheeswaran eighties. This teenybopper love yarn co-starring Vijeta Pandit South Asia: Implications of the work by Elinor Venue & Time: ICC 6.00 p.m. -

Don't Talk About Khalistan but Let It Brew Quietly. Police Say Places Where Religious

22 MARCH 2021 / `50 www.openthemagazine.com CONTENTS 22 MARCH 2021 5 6 12 14 16 18 LOCOMOTIF bengAL DIARY INDIAN ACCENTS TOUCHSTONE WHISPERER OPEN ESSAY The new theology By Swapan Dasgupta The first translator The Eco chamber By Jayanta Ghosal Imperfect pitch of victimhood By Bibek Debroy By Keerthik Sasidharan By James Astill By S Prasannarajan 24 24 AN EAST BENGAL IN WEST BENGAL The 2021 struggle for power is shaped by history, geography, demography—and a miracle by the Mahatma By MJ Akbar 34 THE INDISCREET CHARM OF ABBAS SIDDIQUI Can the sinking Left expect a rainmaker in the brash cleric, its new ally? By Ullekh NP 38 A HERO’S WELCOME 40 46 Former Naxalite, king of B-grade films and hotel magnate Mithun Chakraborty has traversed the political spectrum to finally land a breakout role By Kaveree Bamzai 40 HARVESTING A PROTEST If there is trouble from a resurgent Khalistani politics in Punjab, it is unlikely to follow the 50 54 roadmap of the 1980s By Siddharth Singh 46 TURNING OVER A NEW LEAF The opportunities and pains of India’s tiny seaweed market By Lhendup G Bhutia 62 50 54 60 62 65 66 OWNING HER AGE THE VIOLENT INDIAN PAGE TURNER BRIDE, GROOM, ACTION HOLLYWOOD REPORTER STARGAZER Pooja Bhatt, feisty teen Thomas Blom Hansen The eternity of return The social realism of Viola Davis By Kaveree Bamzai idol and magazine cover on his new book By Mini Kapoor Indian wedding shows on her latest film magnet of the 1990s, is back The Law of Force: The Violent By Aditya Mani Jha Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom By Kaveree Bamzai Heart of Indian Politics -

2 April 2021 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 27 MARCH 2021 Robin Was a Furniture Designer Best Known for His Injection Nali

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 27 March – 2 April 2021 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 27 MARCH 2021 Robin was a furniture designer best known for his injection Nali ...... Nina Conti moulded polypropylene stacking chair, of which over 20 million Libby ...... Sarah Kendall SAT 00:00 Dream Story by Arthur Schnitzler (m000tg86) have been manufactured. Joan ...... Sarah Thom Episode 5 The Days shared a vision of good, affordable design for all. Mrs Singh ...... Nina Wadia Having infiltrated a secret masked ball where the female Together they established themselves as Britain's most Cilla ...... Gbemisola Ikumelo revellers are naked, Fridolin is discovered and must face his celebrated post-war designer couple, often been compared to Zoanna ...... Gbemisola Ikumelo hosts. US contemporaries, Charles Eames and Ray Eames. Roland ...... Colin Hoult Read by Paul Rhys. But despite their growing fame in the 1950s and 60s they Producer: Alexandra Smith Published in 1926, Arthur Schnitzler’s ‘Dream Story’ was remained uncomfortable with the public attention they received. A BBC Studios production for BBC Radio 4 first broadcast in alternately titled ‘Rhapsody’ and, in the original German, They shared a passion for nature and spent more and more time November 2016. ‘Traumnovelle’. outdoors. Lucienne drew much of her inspiration from plants SAT 05:30 Stand-Up Specials (m000tcl3) Credited as the novella that inspired Stanley Kubrick's last film. and flowers and Robin was a talented and obsessive mountain Jacob Hawley: Class Act Translated by JMQ Davies. climber. Stevenage soft lad Jacob Hawley left his hometown behind a Producer: Eugene Murphy Wayne reflects on the many layers to Robin and Lucienne and, decade ago and has ascended Britain's social class system, Made for BBC7 and first broadcast in September 2003. -

KPMG FICCI 2013, 2014 and 2015 – TV 16

#shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 kpmg.com/in ficci-frames.com We would like to thank all those who have contributed and shared their valuable domain insights in helping us put this report together. Images Courtesy: 9X Media Pvt.Ltd. Phoebus Media Accel Animation Studios Prime Focus Ltd. Adlabs Imagica Redchillies VFX Anibrain Reliance Mediaworks Ltd. Baweja Movies Shemaroo Bhasinsoft Shobiz Experential Communications Pvt.Ltd. Disney India Showcraft Productions DQ Limited Star India Pvt. Ltd. Eros International Plc. Teamwork-Arts Fox Star Studios Technicolour India Graphiti Multimedia Pvt.Ltd. Turner International India Ltd. Greengold Animation Pvt.Ltd UTV Motion Pictures KidZania Viacom 18 Media Pvt.Ltd. Madmax Wonderla Holidays Maya Digital Studios Yash Raj Films Multiscreen Media Pvt.Ltd. Zee Entertainmnet Enterprises Ltd. National Film Development Corporation of India with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars: FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 Foreword Making India the global entertainment superpower 2014 has been a turning point for the media and entertainment industry in India in many ways.