IN-WORK POVERTY in the UK: Problem, Policy Analysis and Platform for Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

December 2020 Issue

THEOur Vision: “Successful-LAKER Now and Beyond” REVIEW Volume 41 Calloway County High School Issue 3 2108 College Farm Road, Murray, Ky. 42071 December 18, 2020 Visit city’s Festival of Lights through Jan. 2 Center follows different regulations Hannah Foote Park Recreation Maintenance when the bank approached the park Jewell Gwaltney the MCCATC have had to try to Entertainment Editor Director Steve Wilhelm undertakes offering to first sponsor the show. Staff Writer come up with different ways to pro- the task of setting up the light dis- Murray Bank Marketing Vice Pres- vide a quality education to students, As the holiday season approach- plays throughout the park with oth- ident Tim Stark explained that they The Murray/Calloway County in a hands-on environment, through es, the annual Festival of Lights in ers of the park staff. He usually be- wanted to support the parks. They Area Technology Center (MC- an online venue. Instructors have Murray-Calloway County Central gins setting up in late October and also wanted to help give the com- CATC) offers valuable certifications recorded lessons of themselves actu- Park lights up the night. Many fam- finishes just before Thanksgiving. munity something to look forward in carpentry, culinary arts, automotive ally completing various tasks to share ilies consider driving through the The Murray Bank sponsors the Fes- to. Through their contributions, they technology, electricity, welding, nurs- with students. They have utilized ev- park light displays hope to make the Festi- ing and machine tool. ery facet of Google Suite in addition a long-standing val of Lights a bit larger This year students were only able to online curricula. -

Building Your Chronological Resume

BUILDING YOUR CHRONOLOGICAL RESUME [email protected] 985-876-5861, Option 2 Chronological resumes order information in descending chronological order (most recent to least recent). I suggest making two resumes: a master resume and the resume you will turn into potential employers. Start with your master resume, which lists everything that you’ve done and skills that you have regardless of whether or not it pertains to any specific career or job. Then, make a copy of your master resume and weed out the irrelevant information for the position you want to apply for. (If you decide to make a master resume, make it a chronological resume instead of a skills-based resume as it does not focus on any specific skillset.) Having a master resume helps you to remember what education, experience, training, certifications, etc. you have. That way, when you apply for something new, you won’t have to wrack your brain for anything relevant you can put on it. It’s all right in front of you! MAIN COMPONENTS OF A CHRONOLOGICAL RESUME Name and Contact Information Put your full name in a clear font where it is easy to see. Don’t use a nickname. Most resumes have the individual’s name at the very top of the page in a larger font than any other information. o If you have a common name or know of others with the same name as you, putting a middle name or middle initial can minimize confusion. Put at least two reliable and up-to-date means of contact potential employers can reach you at. -

How-To-Win-Creative-Clients.Pdf

Alex James All Rights Reserved © Alex Mathers 2015 (Alex James) No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the written permission of the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. If you believe this copy was sold to you through an illegitimate source, please notify the author with details of where you got this by contacting [email protected]. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................. 4 Part 1 - Cover Your Bases .......................................................................................... 11 Part 2 - Build Your Value Network ........................................................................... 50 Part 3 - Extra Magic ................................................................................................... 76 Part 4 - Strategy and Taking Action .......................................................................... 95 Full Recap .................................................................................................................102 About the Author .....................................................................................................104 Icon Attribution .......................................................................................................106 Introduction Welcome aboard! On a scale of 1-20, ‘1’ being stone-cold clueless about where to start, and 20 being able to sit back and watch dream clients literally beating at -

Xenoblade Chronicles 3D While I'll Continue to Put in Work on Loz Mini-Games (See Previous Play Journal Entry) and Drop Whatever

Xenoblade Chronicles 3D Play Journal Entries Stagger Lanayru79 11/21/2015 5:11 PM While I'll continue to put in work on LoZ mini-games (see previous Play Journal entry) and drop whatever I'm playing to join a Totem w/ friends, an any% playthrough of my favorite RPG ever will fill my time between now and the first week of December. I have no experience skipping XC Quests, Landmarks and UMs. The goal here is to finish at the lowest level I can. I'll update at major battles, with E Yeah! e 23 r 101 D Advertisement Share this Post 1 Tweet 2 Share Embed Comment AlienSquid 11/21/2015 5:17 PM I'm at the marsh on my first ever playthrough on wii. Loving it so far I don't think I'll make it through before Christmas tho E Yeah! e 1 Stagger 11/21/2015 5:19 PM exponentially less detail than I did during my 100% playthrough last spring. If you're on the edge of your seat for my thoughts on the minutiae of story and gameplay, both the best in the genre I've encountered, those are the posts to look back on. I know the public hungers for my gibberish. :p I'll be marking spoilers from beyond Xord in the comments here. Wish me luck! E Yeah♥ e 1 D Meagan 11/21/2015 5:32 PM I'll be looking forward to your progress. Xenoblade is one of my favorites! E Yeah! e 3 D Justin86 11/21/2015 5:46 PM Getting warmed up for Xenoblade Chronicles X? From what I've seen of gameplay footage, the world in that game may be about as vast as the one in this game, if not larger. -

Spanglish En Canciones Populares Spanglish in Popular Music Magisterská Diplomová Práce

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra romanistiky Spanglish en canciones populares Spanglish in popular music Magisterská diplomová práce Autor: Bc. Markéta Rokosová Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Radim Zámec, Ph. D. Olomouc 2020 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně pod odborným vedením Mgr. Radima Zámce, Ph. D. a uvedla v ní veškerou literaturu a ostatní zdroje, které jsem použila. V Olomouci dne ................................. Podpis……………………………… Poděkování Děkuji vedoucímu mé diplomové práce panu Mgr. Radimovi Zámcovi, Ph.D. za odborné vedení, za pomoc a rady při zpracování této práce. Obsah Introducción ........................................................................................................................... 6 1. Spanglish y su definición ............................................................................................. 8 2. Características de Spanglish ....................................................................................... 10 2.1. Fenómenos lingüísticos .................................................................................... 10 2.1.1. Los préstamos ....................................................................................... 10 2.1.2. Calcos .................................................................................................... 11 2.1.3. El cambio de código ............................................................................. 11 2.2. Español vestigial .............................................................................................. -

Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-2-2017 On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy Evan Nave Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Nave, Evan, "On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 697. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/697 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON MY GRIND: FREESTYLE RAP PRACTICES IN EXPERIMENTAL CREATIVE WRITING AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY Evan Nave 312 Pages My work is always necessarily two-headed. Double-voiced. Call-and-response at once. Paranoid self-talk as dichotomous monologue to move the crowd. Part of this has to do with the deep cuts and scratches in my mind. Recorded and remixed across DNA double helixes. Structurally split. Generationally divided. A style and family history built on breaking down. Evidence of how ill I am. And then there’s the matter of skin. The material concerns of cultural cross-fertilization. Itching to plant seeds where the grass is always greener. Color collaborations and appropriations. Writing white/out with black art ink. Distinctions dangerously hidden behind backbeats or shamelessly displayed front and center for familiar-feeling consumption. -

Learn-2-Earn Reading Program

Learn-2-Earn Reading Program Heavenly Host LLC is partnering with parents to bring you our Learn-2-Earn Reading program. Children often do not understand why reading is important and as a “village” it is our job to find ways to maximize their potential. To scaffold peer and family learning we are offering a way for your children to feel rewarded for their work. We want to bring back the joy and love of literature as well as emphasizing financial literacy. As adults, we expect our pay when we put in work, don’t we? Our children are adults in training, show them that while their true efforts are priceless, their work does deserve reward. How will we do this? The answer is, WITH YOUR HELP! At the beginning of summer, each parent will be given a reading list that is age and grade appropriate. It will be the responsibility of the parent to coordinate with their child to find books that interest them. Through sponsorship and independent partnerships with businesses local and abroad, we want to help create an atmosphere that fosters growth and support. Since this program requires reading, we suggest taking this time to reconnect with your inner child and find the books that gave you that sense of awe. Additionally, since your child is earning this money, it is an avenue to give your child lessons on saving and respecting what they had to work for. We want your child to be excited about learning new things through the unique lens of imagination. We want to reiterate; it takes a village. -

![3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1496/3-smack-that-eminem-feat-eminem-akon-shady-convict-2571496.webp)

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM thing on Get a little drink on (feat. Eminem) They gonna flip for this Akon shit You can bank on it! [Akon:] Pedicure, manicure kitty-cat claws Shady The way she climbs up and down them poles Convict Looking like one of them putty-cat dolls Upfront Trying to hold my woodie back through my Akon draws Slim Shady Steps upstage didn't think I saw Creeps up behind me and she's like "You're!" I see the one, because she be that lady! Hey! I'm like ya I know lets cut to the chase I feel you creeping, I can see it from my No time to waste back to my place shadow Plus from the club to the crib it's like a mile Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini away Gallardo Or more like a palace, shall I say Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Plus I got pal if your gal is game TaeBo In fact he's the one singing the song that's And possibly bend you over look back and playing watch me "Akon!" [Chorus (2X):] [Akon:] Smack that all on the floor I feel you creeping, I can see it from my Smack that give me some more shadow Smack that 'till you get sore Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini Smack that oh-oh! Gallardo Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Upfront style ready to attack now TaeBo Pull in the parking lot slow with the lac down And possibly bend you over look back and Convicts got the whole thing packed now watch me Step in the club now and wardrobe intact now! I feel it down and cracked now (ooh) [Chorus] I see it dull and backed now I'm gonna call her, than I pull the mack down Eminem is rollin', d and em rollin' bo Money -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

The Symbolic Rape of Representation: a Rhetorical Analysis of Black Musical Expression on Billboard's Hot 100 Charts

THE SYMBOLIC RAPE OF REPRESENTATION: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF BLACK MUSICAL EXPRESSION ON BILLBOARD'S HOT 100 CHARTS Richard Sheldon Koonce A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2006 Committee: John Makay, Advisor William Coggin Graduate Faculty Representative Lynda Dee Dixon Radhika Gajjala ii ABSTRACT John J. Makay, Advisor The purpose of this study is to use rhetorical criticism as a means of examining how Blacks are depicted in the lyrics of popular songs, particularly hip-hop music. This study provides a rhetorical analysis of 40 popular songs on Billboard’s Hot 100 Singles Charts from 1999 to 2006. The songs were selected from the Billboard charts, which were accessible to me as a paid subscriber of Napster. The rhetorical analysis of these songs will be bolstered through the use of Black feminist/critical theories. This study will extend previous research regarding the rhetoric of song. It also will identify some of the shared themes in music produced by Blacks, particularly the genre commonly referred to as hip-hop music. This analysis builds upon the idea that the majority of hip-hop music produced and performed by Black recording artists reinforces racial stereotypes, and thus, hegemony. The study supports the concept of which bell hooks (1981) frequently refers to as white supremacist capitalist patriarchy and what Hill-Collins (2000) refers to as the hegemonic domain. The analysis also provides a framework for analyzing the themes of popular songs across genres. The genres ultimately are viewed through the gaze of race and gender because Black male recording artists perform the majority of hip-hop songs. -

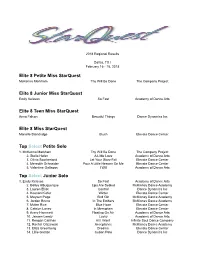

Studio Superlative Awards

2018 Regional Results Dallas, TX I February 16 - 18, 2018 Elite 8 Petite Miss StarQuest McKenna Markham Thy Will Be Done The Company Project Elite 8 Junior Miss StarQuest Emily Kelavos So Fast Academy of Dance Arts Elite 8 Teen Miss StarQuest Anna Falcon Beautful Things Dance Dynamics Inc Elite 8 Miss StarQuest Marielle Standridge Blush Elevate Dance Center Top Select Petite Solo 1. McKenna Markham Thy Will Be Done The Company Project 2. Stella Hafen A Little Love Academy of Dance Arts 3. Olivia Southerland Let Your Glory Fall Elevate Dance Center 4. Meredith Schneider Pour A Little Heaven On Me Elevate Dance Center 5. Valentine Gallegos I Will Academy of Dance Arts Top Select Junior Solo 1. Emily Kelavos So Fast Academy of Dance Arts 2. Bailey Albuquerque Lips Are Sealed McKinney Dance Academy 3. Lauren Elliot Control Dance Dynamics Inc 4. Keenan Kiefer Winter Elevate Dance Center 5. Maysen Page Bird Girl McKinney Dance Academy 6. Jordan Bruno In The Embers McKinney Dance Academy 7. Mylee Rice Blue Haze Elevate Dance Center 8. Catelyn Laney In Memoriam Elevate Dance Center 9. Avery Hammett Floating On Air Academy of Dance Arts 10. Jensen Leedy Lucky Academy of Dance Arts 11. Reagan Callihan All I Want Infinite Soul Dance Company 12. Rachel Olszewski Acceptance McKinney Dance Academy 13. Eliza Greenberg Dreams Elevate Dance Center 14. Lillie Gaston Cuban Pete Dance Dynamics Inc 15. Chloe Lane Respect Academy of Dance Arts Top Select Teen Solo 1. Delaney Vasquez Gorgeous Elevate Dance Center 2. Amira Williams Easier Academy of Dance Arts 3.